This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Abstract

Objectives

Airway management in patients with panfacial trauma is complicated. In addition to involving facial lesions, such trauma compromises the airway, and the use of intermaxillary fixation makes it difficult to secure ventilation by usual approaches (nasotracheal or endotracheal intubation). Submental airway derivation is an alternative to tracheostomy and nasotracheal intubation, allowing a permeable airway with minimal complications in complex patients.

Materials and Methods

This is a descriptive, retrospective study based on a review of medical records of all patients with facial trauma from January 2003 to May 2015. In total, 31 patients with complex factures requiring submental airway derivation were included. No complications such as bleeding, infection, vascular, glandular, or nervous lesions were presented in any of the patients.

Results

The use of submental airway derivation is a simple, safe, and easy method to ensure airway management. Moreover, it allows an easier reconstruction.

Conclusion

Based on these results, we concluded that, if the relevant steps are followed, the use of submental intubation in the treatment of patients with complex facial trauma is a safe and effective option.

Go to :

Keywords: Submental derivation, Complex facial trauma, Safety, Efficacy

I. Introduction

Airway management in patients with complex facial trauma is quite challenging due to anatomical distortion that causes difficult oral and nasal intubation. Therefore, it is necessary to seek alternative techniques to secure the airway before and after a surgical procedure

1.

Commonly, the airway is secured through endotracheal intubation. However, in patients with complex facial trauma involving cervical spinal cord injury, skull base fracture with or without rhinorrhea, nasal anatomy distortion, or lack of anesthesiologist experience, it is not possible to perform endotracheal intubation. In addition, many of these patients require intermaxillary fixation (IMF) in order to maintain normal dental occlusion transoperatively, which does not allow the use of orotracheal intubation because of the need for transient dental occlusion

123.

One common option is tracheostomy, which is suggested for patients with severe head trauma that require ventilatory support for a prolonged period of time or in patients with polytrauma that will undergo several consecutive surgeries. However, this alternative includes multiple risks such as tracheal stenosis, tracheoesophageal fistula, bleeding, wound infection, recurrent laryngeal nerve injury, and visible scar

4.

Another valid option not so commonly used due to its need for surgical experience is submental derivation. Described in 1986 by Hernández Altemir

2, it promotes the establishment of a permeable and safe airway in patients with severe facial skeleton fractures, mainly those presenting with mid-third facial injury. This method facilitates management of the surgical area and the IMF, which is of vital importance for bone reconstruction

45.

Submental derivation is an ideal alternative because it is a simple procedure that has the same advantages of nasal or orotracheal intubation to perform intraoperative IMF. It also allows the management of concomitant nasal or nasoorbitoethmoidal fractures

1.

The contraindications of this procedure are that the patient refuses treatment, hemorrhagic diathesis, laryngotracheal disruption, surgical site infection, gunshot wound of the maxillofacial area, the need for prolonged mechanic ventilation, tumor ablation in the maxillofacial region, or past history of keloid scarring

6.

The submental derivation procedure has its complications during the intraoperative time, such as sublingual and submental gland injury with its required ducts and lingual nerve injury. In the postoperative period, edema, obstruction, hematoma, lower airway infection, mucocutaneous fistula, and mucocele can develop

78.

This study presents our experience in the use of submental derivation as a valid alternative for airway management in patients with complex facial trauma.

The study was approved by the Health Research Committee and Research Ethics of ISSEMyM Medical Center (approval no. 203F 39101/1000/CMI/51/2018), and informed consent was obtained.

Go to :

II. Materials and Methods

This is a descriptive, retrospective study based on a review of medical records of all patients with facial trauma from January 2003 to May 2015. We included patients with midface Le Fort fractures I, II, and III and nasoorbitoethmoidal fractures in which intubation by submental derivation was indicated (impossibility for nasotracheal or orotracheal intubation and need for transient dental occlusion), regardless of age, sex, or trauma mechanism.

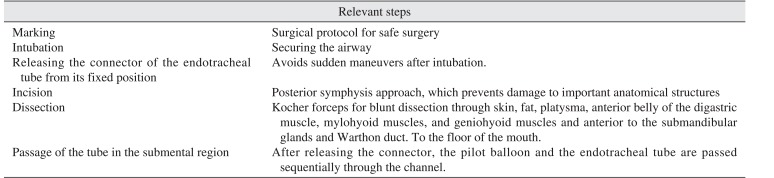

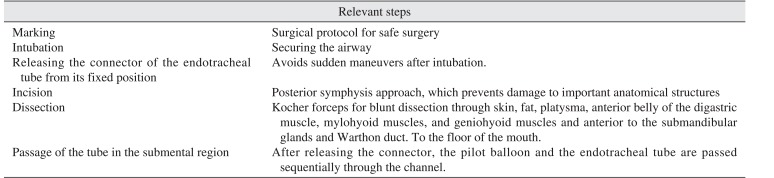

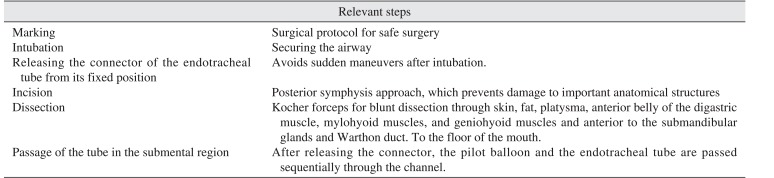

We followed a specific sequence to avoid complications and to make the process easily reproducible through identified critical steps.(

Table 1) Prior intubation and, for patient and airway security, releasing the connector of the endotracheal tube is necessary in order to avoid further complications.

Table 1

Relevant steps for submental intubation

|

Relevant steps |

|

Marking |

Surgical protocol for safe surgery |

|

Intubation |

Securing the airway |

|

Releasing the connector of the endotracheal tube from its fixed position |

Avoids sudden maneuvers after intubation. |

|

Incision |

Posterior symphysis approach, which prevents damage to important anatomical structures |

|

Dissection |

Kocher forceps for blunt dissection through skin, fat, platysma, anterior belly of the digastric muscle, mylohyoid muscles, and geniohyoid muscles and anterior to the submandibular glands and Warthon duct. To the floor of the mouth. |

|

Passage of the tube in the submental region |

After releasing the connector, the pilot balloon and the endotracheal tube are passed sequentially through the channel. |

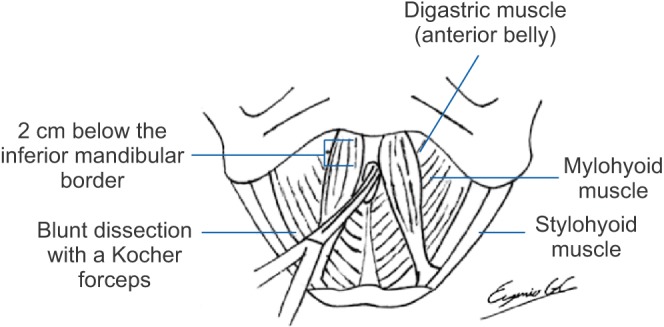

The anesthesiology team started the orotracheal intubation with an armed endotracheal tube according to patient measurements. Once the airway was secured, the patient was sterilely prepped and draped in the usual fashion. We proceeded corto mark a 1.5 cm horizontal line 2 cm below the inferior mandibular border. Then, we administered 2% lidocaine with epinephrine in the symphysis region.(

Fig. 1)

| Fig. 1Incision mark.

|

An incision was made only on the skin over the previously marked line, and blunt dissection was performed with Kocher forceps in a caudal-cephalic fashion over the midline close to the mandibular symphysis, through the subcutaneous tissue, while maintaining the dissection at the midline and avoiding the mylohyoid muscles and the anterior belly of the digastric muscle.(

Fig. 2,

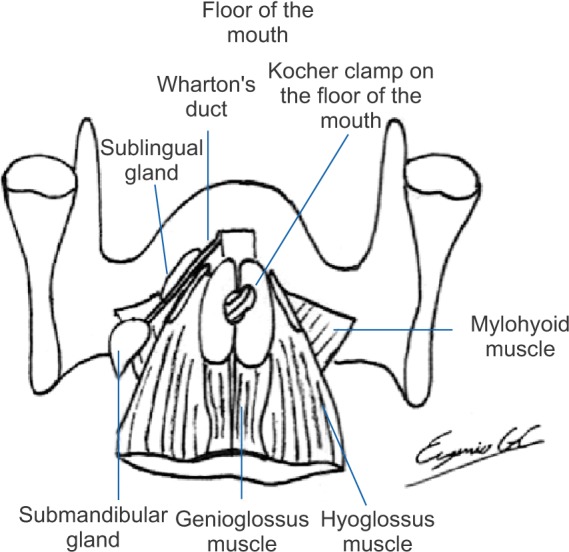

3) We continued all the way though the geniohyoid muscles and anterior to the submandibular glands and Wharton's duct, to finally disrupt the lingual vestibular mucosa and to observe the forceps through the mucosa of the floor of the mouth.(

Fig. 4,

5)

| Fig. 2Blunt dissection through incision.

|

| Fig. 3Schematization of anatomical structures around the dissection.

|

| Fig. 4Visualization of the Kocher clamp on the floor of the mouth.

|

| Fig. 5Schematization of anatomical structures around the dissection on the floor of the mouth.

|

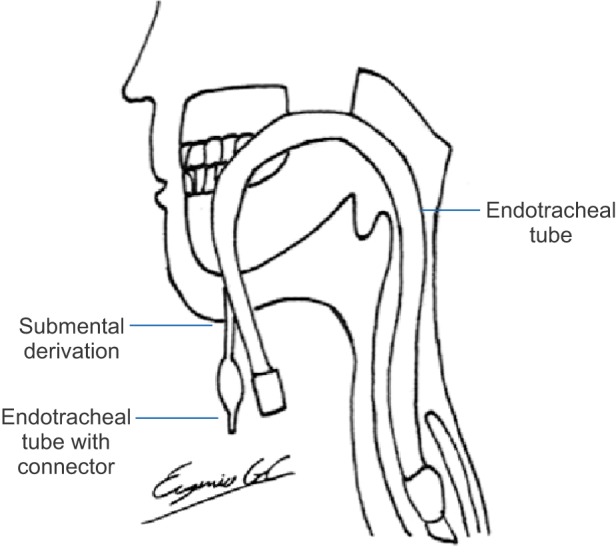

Once the tunnel is created, the previously released orotracheal tube connector is removed, and the tube is packed with sterile gauze to prevent the entrance of any fluid. The balloon insufflator is first applied with a clamp, and smooth traction is performed through the dissection toward the submandibular area. Then, the same procedure is performed with the distal end of the tube, while always manually securing the tube in its proximal portion.(

Fig. 6) The gauze packing is removed, and the connector is placed (

Fig. 7); confirmation of the correct endotracheal tube position is made by capnography and bilateral auscultation of lung fields. Fixation with #0 silk is done to join the tube to the ventilation system. It is then fixed with the same suture to the skin, hemostasis is verified, and the procedure is finished.(

Fig. 8)

| Fig. 6Passage of the endotracheal tube through the dissection channel.

|

| Fig. 7Fixation of the endotracheal tube.

|

| Fig. 8Schematization of final endotracheal tube position.

|

At the end of the surgery, the connector is once again removed, and the proximal portion of the tube is stabilized. The tube is moved in a retrograde manner to the oral cavity, and the globe is passed through it.

The subcutaneous tissue is closed with Vicryl 4-0 inverted knots, and the skin is closed with Nylon 5-0. Secondary healing closes the intraoral wound.

We performed this procedure in a systematic fashion, following the steps mentioned in

Table 1.

Go to :

III. Results

None of the 31 patients included in this study developed any of the intraoperative complications secondary to this procedure as described in the literature

4, nor in the immediate postoperative period or during the outpatient follow-up period.

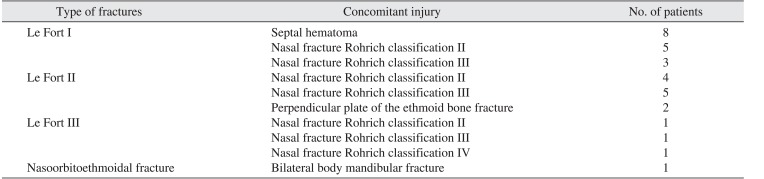

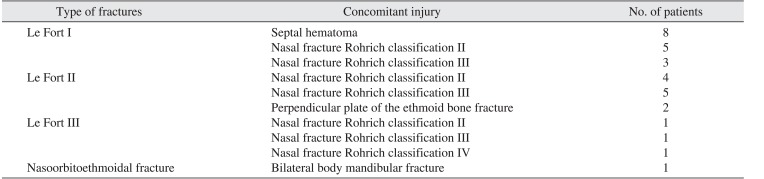

The age range of the 31 patients was 14 to 71 years (mean age, 35.5 years); 27 patients were men, while four were women.

The trauma mechanism in most cases was car accident or gunshot. With regard to type, 78% were closed trauma, and the remaining 22% were open trauma. Fracture management was realized in all cases with IMF and open reduction and internal fixation with osteosynthesis material, with an mean time between trauma occurrence and surgery of 4.26 days (range, 1–20 days).

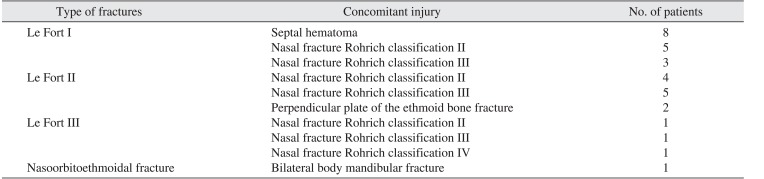

Of the 31 patients, 16 patients had a Le Fort fracture type I, 11 patients had a Le Fort fracture type II, three patients had a Le Fort fracture type III, and one patient had a nasoorbitoethmoidal fracture. The concomitant injuries are shown in

Table 2.

Table 2

Distribution of concomitant lesions

|

Type of fractures |

Concomitant injury |

No. of patients |

|

Le Fort I |

Septal hematoma |

8 |

|

Nasal fracture Rohrich classification II |

5 |

|

Nasal fracture Rohrich classification III |

3 |

|

Le Fort II |

Nasal fracture Rohrich classification II |

4 |

|

Nasal fracture Rohrich classification III |

5 |

|

Perpendicular plate of the ethmoid bone fracture |

2 |

|

Le Fort III |

Nasal fracture Rohrich classification II |

1 |

|

Nasal fracture Rohrich classification III |

1 |

|

Nasal fracture Rohrich classification IV |

1 |

|

Nasoorbitoethmoidal fracture |

Bilateral body mandibular fracture |

1 |

Go to :

IV. Discussion

Airway management in patients with maxillofacial trauma is difficult due to concomitant injuries. The normal anatomy distortion complicates endotracheal intubation, laryngoscopy, and the insertion of oropharyngeal cannulas. It is also indispensable in cases involving fracture of the mid-third of the facial skeleton to maintain the patients in normal occlusion and to perform internal fixation. The use of submental derivation has allowed the securement of a permeable airway in an easy and effective way

9101112.

Submental derivation was described by Hernández Altemir

2 in 1986 as an alternative to tracheostomy in patients with facial trauma

5. MacInnis and Baig

10 in 1999 described the incision in an inferior direction between the genioglossus muscle, the geniohyoid muscle, and the anterior belly of the digastric muscle. They also proposed their indication criteria: (1) minimum neurological deficit, (2) traumatic craniomaxillofacial injury, (3) need for intraoperative IMF for a short period of time to perform fracture reduction and fixation, (4) large pharyngeal flaps, and (5) rhinoplasty and craniomaxillofacial surgery

13.

This type of airway management also avoids injury to nasal structures and the risk of cranial disruption with insertion of a tube into the cranial cavity, allowing manipulation of bone segments and tracheostomy exclusion. It is the preferred method of airway control in patients with maxillofacial fractures that do not require endotracheal intubation for more than 48 hours and patients in which nasotracheal intubation is not feasible

4. A common alternative is tracheostomy, which requires a major surgical dissection and manipulation of important anatomical structures, as well as greater surgical time. Recurrent laryngeal nerve injury, thyroid gland injury hemorrhage, and tracheoesophageal fistulas are avoided

9.

Patients with Le Fort II and III fractures, which involve the crib-shaped plate, have greater risks during nasotracheal intubation, such as cranial intubation, epistaxis, pharynx injury, nostril necrosis, otitis media, sinusitis, sepsis, and the impossibility to move the tube through the nose

114. Orotracheal intubation does not allow the reduction and stabilization of the maxilla and mandible

1. The advantages reported with submental derivation include: (1) avoidance of inherent complications of nasotracheal intubation and tracheostomy, (2) a simple procedure with low morbidity, (3) does not interfere with intraoral manipulation and maxillomandibular fixation, (4) can be used in patients with elective orthognathic surgery and patients with nasal obstruction such as cleft lip and palate patients, and (5) allows manipulation and treatment of the entire facial complex, with immediate withdrawal of IMF after the treatment is finished

4.

Nonetheless, there exist potential complications of submental derivation such as superficial infection, mucocutaneous fistula, mucocele, sublingual and submaxillary gland and duct injury, and lingual nerve injury. Meyer et al.

15 reported an 8% occurrence of oral floor abscesses and a 4% incidence of hypertrophic scar formation in a sample size of 25 patients

16. However, none of these complications were presented in the 31 patients in which submental derivation was used through a midline approach. This demonstrates that, if the technique is performed meticulously and following the essential steps as described in

Table 1, complications can be avoided, allowing appropriate IMF and a better approach for the treatment of complex facial fractures. Any surgeon could easily and safely perform this technique without expecting the same major complications that are currently associated with tracheostomy.

Go to :

V. Conclusion

If the relevant steps in the sequence proposed by our experiments are followed, the use of submental intubation is a safe and effective alternative for airway management in patients with facial trauma and concomitant injuries that do not allow the use of nasotracheal or orotracheal intubation. This method also avoids tracheostomy and its inherent complications. The performance of this technique could easily and safely be done by any surgeon following the described steps and sequence.

Go to :