Abstract

Objectives

Idiopathic bone cavity (IBC) is an uncommon intra-osseous cavity of unknown etiology. Clinical features of IBC are not well known and treatment modalities of IBC are controversial. The purpose of this study was to investigate the clinical characteristics of 27 IBC patients who underwent surgical exploration.

Materials and Methods

A total of 27 consecutive patients who underwent surgery due to a jaw bone cavity from April 2006 to February 2016 were included in this study. Nine male and 18 female patients were enrolled. Patients were examined retrospectively regarding primary site, history of trauma, graft material, radiographic size of the lesion, presence of interdental scalloping, erosion of the inferior border of the mandible, complications, results of bone graft, and recurrence.

Results

Female dominance was found. Maxillary lesion was found in one patient, and bilateral posterior mandibular lesions were found in two patients. The other patients showed a single mandibular lesion. The posterior mandible (24 cases) was the most common site of IBC, followed by the anterior mandible (5 cases). Two patients with anterior mandibular lesion reported history of trauma due to car accident, while the others denied any trauma history. Radiographic cystic cavity length over 30 mm was found in 10 patients. Seven patients showed erosion of the mandibular inferior border. The operations performed were surgical exploration, curettage, and bone or collagen graft. One bilateral IBC patient showed recurrence of the lesion during follow-up. Grafted bone was integrated into the native mandibular bone without infection. One patient reported necrosis of the mandibular incisor pulp after operation.

Conclusion

Differential diagnosis of IBC is difficult, and IBC is often confused with periapical cyst. Surgical exploration and bone graft are recommended for treating IBC. Endodontic treatment of involved teeth should be evaluated before operation. Bone graft is recommended to reduce the healing period.

Idiopathic bone cavity (IBC) which was previously described as a traumatic bone cyst, is an uncommon jaw bone lesion of unknown etiology1234. The term “traumatic bone cyst” first appeared in a study by Blum5 in 1929, and trauma was considered as an etiology. IBC shows no epithelial lining and an intact bony wall, and the cavity is usually filled with fluid with no evidence of acute or chronic inflammation23. In 2012, the World Health Organization defined IBC as a nonneoplastic intraosseous pseudocyst devoid of epithelial lining 6. IBCs account for 1% of jaw lesions7, and they are usually discovered in routine radiographic examination. Because IBC is usually located in the apex of a tooth, differentiating it from periapical cyst can be quite difficult. Periapical cyst needs cyst enucleation and apicoectomy with/without retrograde root filling; however, IBC does not need cyst enucleation or apicoectomy. Vitality of the involved teeth is the main criterion for endodontic treatment; however, vital pulp is found in both IBC and periapical cyst.

Although trauma has been suggested as a cause of IBC, other hypotheses include blockage of lymphatic drainage, developmental anomalies, and osteolysis secondary to altered bone metabolism8. Treatment of IBC involves surgical exploration that typically reveals an empty cavity with or without bone graft. To date, there is no consensus on treatment modality for IBC of the jaw because of the rarity of the disease. Some clinicians have found that IBCs do not need surgical intervention because they heal spontaneously91011, but others have suggested that IBCs resolve only after surgical treatment 1213. The natural characteristics including the etiology and optimal management of IBCs have not been elucidated.

Resnick et al.4 reported a management strategy for IBC with a review of 45 cases. However, no case series or review articles have been reported in Korea. The purpose of this study was to report the clinical characteristics of IBCs and the surgical treatment and outcomes of 27 Korean patients. We hope to suggest a standard protocol for management of IBC.

A total of 27 consecutive patients with 30 IBCs who underwent surgical exploration at Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine from April 2006 to February 2016 by one experienced oral and maxillofacial surgeon were included in this study. To be included in the study, patients must have had an IBC of the jaw confirmed by observation of a bone cavity during surgical exploration. Patients' medical records and radiographs were examined retrospectively regarding age, sex, primary sites, history of trauma, graft material, size of the lesions, performance of endodontic treatment in involved teeth, erosion of the mandibular inferior border, and recurrence. Panoramic radiography was performed for initial diagnosis. Cortical erosion of the inferior border of the mandible was examined. Cone-beam computed tomography (CT) was performed for size measurement and to examine buccal cortex erosion. Longest defect size was measured in mesiodistal and superior-inferior regions. Consultation with an endodontist was performed to evaluate the vitality of the involved teeth using the electric pulp test. Differential diagnosis between IBC and periapical cyst was performed using radiographic and clinical examination. The institutional review board of our center issued an exemption to this study because of the use of existing data in such a manner that subjects cannot be identified directly, and the study was performed retrospectively with medical records and radiographs.

The surgical procedure was performed under local or general anesthesia according to age and severity of dental phobia. Crevicular incision was performed to approach the lesion, and a round bur was used to create a bony window. Fluid inside of the IBC was aspirated, and simple curettage of the cavity wall was performed. Apicoectomy was not performed in all cases. Since the lesion lacks cyst lining and soft tissue content, no pathologic sample was harvested. Allogenic bone (Exfuse; Hanmi Co., Seoul, Korea) or collagen plug (Ateloplug; Bioland Co., Osong, Korea) was inserted into the bone cavity. Allogenic bone was grafted when primary closure of the lesion was possible. A panoramic radiograph was taken immediately after the operation and 1 month, 3 months, 6 months, and 1 year after the operation. Subsequently, followup was performed every year. Recurrence or second primary lesions were evaluated with panoramic radiographs. Clinicians looked for postoperative complications such as infection, nerve damage, pulp necrosis, or failure of bone graft.

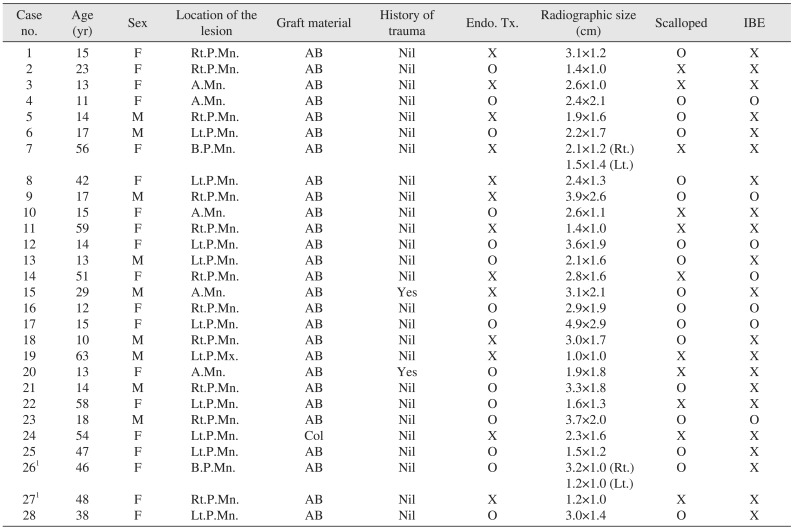

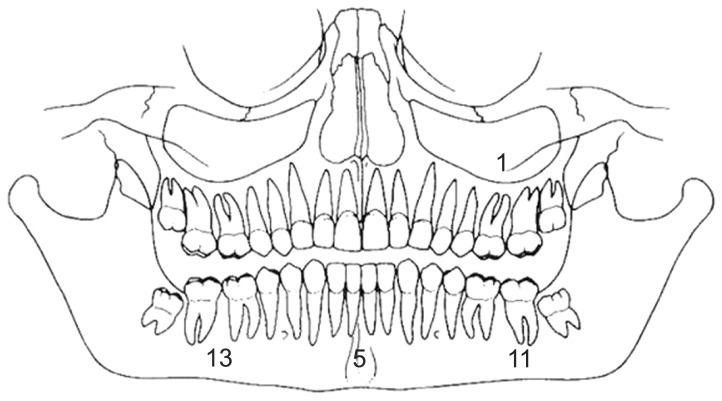

A total of 27 patients were included in the present study. Features of the 27 patients are summarized in Table 1 (Case nos. 26 and 27 are the same patient with recurrence). The male to female ratio was 1:2, showing female dominance. The mean patient age at the first visit to our department was 29.5±18.7 years (range, 10-63 years). Fifteen patients were aged between 10 and 19 years.(Fig. 1) The distribution of the lesions is described in Fig. 2. The posterior mandible was the most common site of IBC (right, 13 cases; left, 11 cases), and the anterior mandible was the second site (5 cases). Bilateral mandibular lesions were found in two patients (Case no. 7, Fig. 3; Case no. 26, Fig. 4. A). Case nos. 26 and 27 represent a single patient with IBC of the jaw that recurred on the right side of the mandible after two years.(Fig. 4. B) The other patients showed a single lesion in the mandible except one maxillary lesion.(Fig. 5)

Seven patients showed erosion of the mandibular inferior border (23.3%). There was no perforation of the buccal cortex in any patient; however, there was one patient (Case no. 26) who showed crestal bone erosion in the left mandible. Defect size over 30 mm was found in 10 cases (33.3%). The largest diameter of the lesion was 49 mm, observed in Case no. 17. Scalloping of the inter-radicular alveolar bone was found in 17 cases (56.7%). There were no symptoms in all patients, and all lesions were identified through routine dental screening or during orthodontic treatment. Two patients with anterior mandibular lesions (Case nos. 15 and 20) reported trauma history due to a car accident. Healing was uneventful after operation in all except one female patient. One patient reported necrosis of the pulp at the mandibular anterior central incisors. An anterior mandibular lesion with involvement of teeth #31 and #41 was curetted and bone grafted. Pulp necrosis with discoloration of the teeth was found 2 weeks after operation. Postoperative endodontic treatment was performed 4 weeks after operation. Bone graft was integrated with native bone within 1 year.

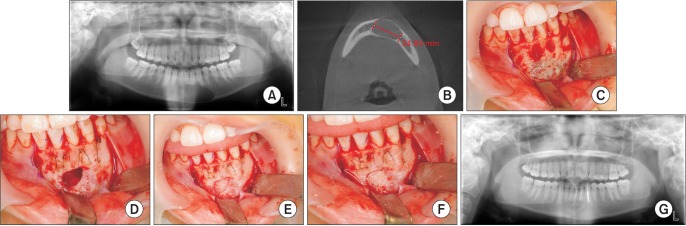

In September 2010, a 11-year-old female patient (Case no. 4; Table 1) was referred from a dental clinic for evaluation of a radiolucent lesion in the anterior mandible. The lesion was discovered incidentally on radiographs obtained for orthodontic treatment. A panoramic radiograph showed a single, unilocular, corticated, well-defined, radiolucent lesion from tooth #31 to #34.(Fig. 6. A) Erosion of the inferior border of the mandible was found. Cone-beam CT scan revealed 24.93 mm sized bone defect in the longest length.(Fig. 6. B) Scalloping of the interdental bone was found.

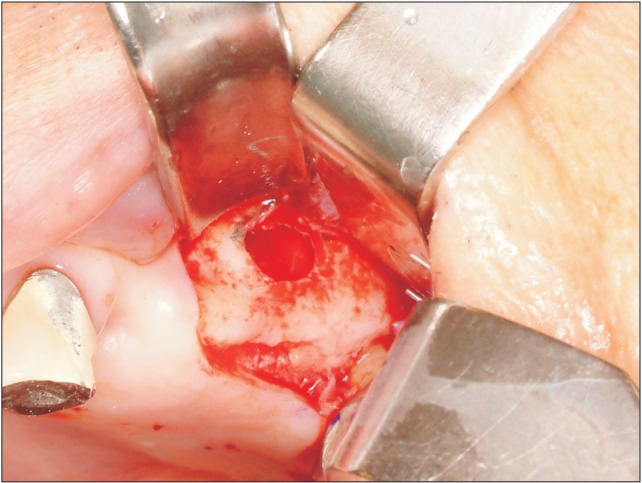

In accordance with the clinical and radiographic findings, the patient was tentatively diagnosed with an odontogenic cyst or IBC. Exploratory surgery was planned, and endodontic treatment of teeth #31, #32, and #33 was completed before the operation after consultation with an endodontist. At the time of the procedure, an acrevicular incision was made for approaching the lesion under general anesthesia. A full-thickness flap was elevated, and the anterior mandible was exposed.(Fig. 6. C) After the bony window was created, an empty bone cavity with fluid and no epithelial lining were observed.(Fig. 6. D) The bony window was covered with saline gauze to prevent desiccation. A diagnosis of IBC was confirmed, and surgical exploration with simple curettage was performed. The bone cavity was filled with allogenic bone.(Fig. 6. E) Finally, the bone defect was covered by the window bone that had been temporarily removed.(Fig. 6. F) A postoperative panoramic radiograph was obtained at 1 year.(Fig. 6. G) Grafted bone was integrated into the native mandibular bone without infection. There was no recurrence of the lesion during follow-up.

Many authors have reported that IBCs are most commonly seen in the mandibular body and can present at multiple sites14. In our study, the most common site for IBCs was the posterior mandible, and a maxillary lesion was found in one patient. There is much evidence that trauma could be a cause of IBCs in the anterior mandible7. In our study, 2 out of 27 patients (7.4%) stated that they had been involved in a car accident in the past. Trauma has been considered one of the main cause of IBC in the anterior mandibular area; however, more study with a large number of patients is required.

The differential diagnosis of IBC includes odontogenic cysts like periapical cyst and odontogenic tumors such as keratocystic odontogenic tumor15. Some radiographic findings such as intact lamina dura and interdental scalloping can help in diagnosing IBCs, but they are not definite diagnostic criteria. Instead of radiographic and clinical features, IBC can be diagnosed definitely on the perioperative view of a bone cavity without biopsy during operation. In our study, endodontic treatment of involved teeth was performed in consultation with an endodontist. If a periapical cyst was suspected, preoperative endodontic treatment was performed.

There is no consensus on treatment modalities for IBCs of the jaw. Some researchers have reported that IBCs regress spontaneously without surgical intervention91011. Others have claimed that bone graft is unnecessary because the presence of blood within the lesion cavity after an operation, from curettage or injection of autologous blood, triggers mesenchymal cell differentiation and bone production16. On the contrary, others have suggested that the lesions require surgical intervention, as in our study1213. In the present report, surgical exploration with simple curettage was performed, and the bone cavity was filled with allogenic bone or collagen. Resnick et al.4 reported a standard surgical protocol for surgical exploration using only simple curettage. They did not fill the cavity with bone or other graft materials. They described that only 50% of the patients showed bone healing after operation. Allogenic bone graft in IBCs has many advantages such as early bone healing, prevention of soft tissue ingrowth, and easily identified recurrence. Some studies have concluded that IBC in the jaw persists at a greater rate than previously reported417. In our study, only one patient (3.7%) showed recurrence of the lesion, while a recent study has reported the recurrence rate of IBC in facial bone to be about 20%18. Based on the finding of no recurrence or post-operative infection during follow-up, a treatment strategy involving simple curettage and bone graft seems to be the most effective way to manage idiopathic bone cavities of the jaw.

References

1. Gowgiel JM. Simple bone cyst of the mandible. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1979; 47:319–322. PMID: 285400.

2. Kuhmichel A, Bouloux GF. Multifocal traumatic bone cysts: case report and current thoughts on etiology. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010; 68:208–212. PMID: 20006180.

3. Rushton MA. Solitary bone cysts in the mandible. Br Dent J. 1946; 81:37–49. PMID: 20992458.

4. Resnick CM, Dentino KM, Garza R, Padwa BL. A management strategy for idiopathic bone cavities of the jaws. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2016; 74:1153–1158. PMID: 26850870.

5. Blum T. Do all cysts of the jaws originate from the dental system? (With a report of two nondental cysts lined with ciliated columnar epithelium). J Am Dent Assoc. 1929; 16:647–661.

6. Coindre JM. New WHO classification of tumours of soft tissue and bone. Ann Pathol. 2012; 32(5 Suppl):S115–S116. PMID: 23127926.

7. Harnet JC, Lombardi T, Klewansky P, Rieger J, Tempe MH, Clavert JM. Solitary bone cyst of the jaws: a review of the etiopathogenic hypotheses. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008; 66:2345–2348. PMID: 18940504.

8. Velez I, Cardenas LE, Evans B. Idiopathic bone cavity mimics odontogenic lesion. Todays FDA. 2006; 18:21–23. PMID: 17936946.

9. Damante JH, Da S, Ferreira O Jr. Spontaneous resolution of simple bone cysts. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2002; 31:182–186. PMID: 12058266.

10. Sapp JP, Stark ML. Self-healing traumatic bone cysts. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1990; 69:597–602. PMID: 2333212.

11. Szerlip L. Traumatic bone cysts. Resolution without surgery. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1966; 21:201–204. PMID: 5215981.

12. Chapman PJ, Romaniuk K. Traumatic bone cyst of the mandible; regression following aspiration. Int J Oral Surg. 1985; 14:290–294. PMID: 3926675.

13. Howe GL. ‘Haemorrhagic cysts’ of the mandible. I. Br J Oral Surg. 1965; 3:55–76. PMID: 5330325.

14. Copete MA, Kawamata A, Langlais RP. Solitary bone cyst of the jaws: radiographic review of 44 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1998; 85:221–225. PMID: 9503460.

15. Shigematsu H, Fujita K, Watanabe K. Atypical simple bone cyst of the mandible. A case report. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1994; 23:298–299. PMID: 7890974.

16. Precious DS, McFadden LR. Treatment of traumatic bone cyst of mandible by injection of autogeneic blood. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1984; 58:137–140. PMID: 6592506.

17. Schreuder HW, Conrad EU 3rd, Bruckner JD, Howlett AT, Sorensen LS. Treatment of simple bone cysts in children with curettage and cryosurgery. J Pediatr Orthop. 1997; 17:814–820. PMID: 9591989.

18. Suei Y, Taguchi A, Tanimoto K. Simple bone cyst of the jaws: evaluation of treatment outcome by review of 132 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007; 65:918–923. PMID: 17448841.

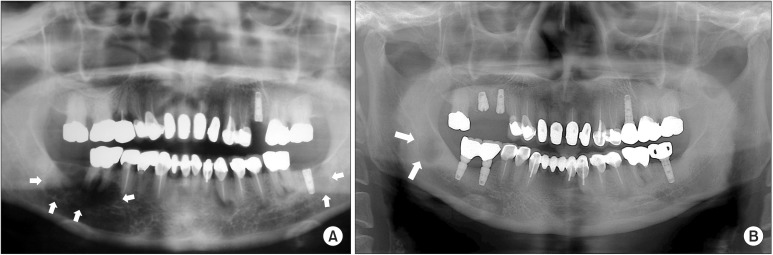

Fig. 4

A. Bilateral idiopathic bone cavities in the posterior mandible (arrows). B. Recurrence of the lesion in the right posterior mandible two years after first operation (arrows).

Fig. 6

A. Preoperative panoramic radiograph of the patient with idiopathic bone cavity in the anterior mandible. B. Cone-beam computed tomography showing bone cavity with cortical bone resorption. C. Surgical exposure of the anterior mandible with crevicular and vertical incision. Erosion of the cortical bone is observed. D. Creation of bone window for removal of fluid and curettage. E. Allogenic bone graft in the bone cavity. F. Bony window reposition. G. Panoramic radiograph one year after operation.

Table 1

Features of idiopathic bone cavities in 30 cases

(F: female, M: male, Rt.: right, Lt.: left, B.: both, A.: anterior, P.: posterior, Mn.: mandible, Mx.: maxilla, AB: allogenic bone, Col: collagen, Nil: no, Endo. Tx.: preoperative endodontic treatment, IBE: erosion of the inferior border of the mandible)

1Case nos. 26 and 27 are the same patient with recurrence.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download