Abstract

The tympanic plate is a small part of the temporal bone that separates the mandibular condyle from the external auditory canal. Fracture of this small plate is rare and usually associated with other bony fractures, mainly temporal and mandibular bone. There is a limited amount of literature on this subject, which increases the chance of cases being overlooked by physicians and radiologists. This is further supported by purely isolated cases of tympanic plate fracture without evidence of other bony fractures. Cone-beam computed tomography is an investigative three-dimensional imaging modality that can be used to detect fine structures and fractures in maxillofacial trauma. This article presents four cases of isolated tympanic plate fracture diagnosed by cone-beam computed tomography with no evidence of fracture involving other bones and review of the literature.

The tympanic plate is the thin bony plate anterior to the external auditory meatus, separating it from the condyle1. It is an important anatomic structure because of its critical neurovascular relation to the base of the cranium and otologic structures and proximity to the temporomandibular joint (TMJ)1. Tympanic plate fractures (TPFs) are uncommon and are usually associated with trauma to the temporal or mandibular bone, with or without additional fractures123. In cases of trauma to mandible, the forces are absorbed by the soft tissue posterior to condyle and, if present, by the fracture itself. Trauma to the mandible can displace the condyle posteriorly, laterally, and superiorly, displacing into the external auditory canal (EAC), temporal fossa, and middle cranial fossa4567. As the condyle is separated from the EAC by the tympanic plate, its posterior displacement is responsible for TPF. Posterior displacement or dislocation of the mandibular condyle is very rare; thus, TPF secondary to mandibular trauma is also very rare8. Trauma to the temporal fossa could be associated with either a TPF or an accompanying fracture in the petrous part of temporal bone9. TPF associated with temporal bone fracture can also be associated with skull fractures or other mid-face fractures and can be seen in all fracture plane orientations of temporal bone fractures10. TPF are more commonly associated with longitudinal temporal bone fracture compared to the transverse type11. Recently, cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) has gained momentum as a diagnostic approach for maxillofacial pathologies, including maxillofacial trauma. This is a three-dimensional (3D) imaging modality comparable to computed tomography (CT) and is available in most dental hospitals; it has become the primary investigative procedure for diagnosing acute maxillofacial trauma cases.

This paper presents four isolated cases of TPF detected by CBCT imaging, along with a review of the literature.

All patients reported to the Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology at our institute. A CBCT was performed after thorough clinical examination.

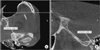

A 28-year-old male patient reported craniofacial injuries and a history of bleeding from the left ear after falling from his bike. Clinical examination revealed soft tissue injury, EAC bleeding, pain in the left preauricular region, and reduced TMJ movement with normal occlusion. CBCT scans confirmed the presence of left TPF and partial obliteration of the EAC.(Fig. 1) The patient was treated conservatively and was symptom-free in one month.

A 23-year-old male patient with a history of trauma to the face while playing football reported right ear bleeding, hypoacusis, and painful partial trismus. Clinical examination confirmed bleeding from the ear and tenderness in the right preauricular area with reduced TMJ movement. CBCT scans showed right side TPF, complete obliteration of the EAC, and partial obliteration of mastoid air cells.(Fig. 2) The patient was treated conservatively and regained normal hearing in two weeks.

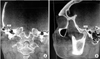

A 26-year-old male patient presented with bleeding from the left ear and severe trismus after a traffic accident four days prior. Clinical examination confirmed left hemotympanum and severe painful trismus. CBCT examination revealed comminuted fracture involving the left tympanic plate and complete obliteration of the EAC.(Fig. 3) The patient was treated conservatively, and the symptoms resolved in three months.

A 25-year-old male patient presented with moderate pain in the right preauricular region. The patient had a history of fall and a direct hit to the mandible. History of bleeding and inability to open his mouth were also reported. Clinical examination revealed pain in the right preauricular region that was exacerbated on mouth opening and presence of edema in the EAC. CBCT showed a right TPF and complete obliteration of the EAC.(Fig. 4) The patient was advised to follow conservative treatment, and symptoms subsided within five weeks.

TPF is associated with temporal and mandibular bone fractures, but not all temporal and mandibular bone fractures are associated with TPF1. Possible explanations for this could be the high intensity of force; direction of trauma; type of trauma, including road traffic accidents, falls, assault, sports, iatrogenic, or other reasons1213; open mouth during trauma1415; thin tympanic bone5; absence of posterior teeth14; condylar morphology abnormalities; and temporal bone pneumatization8.

Patients with TPF can present with a wide range of clinical features. These clinical features include hemorrhage or edema involving the EAC, deep pain within the ear and preauricular region, hypoacusis, and trismus, which can manifest immediately after trauma or have a delayed onset1415. These observations can also be noted in maxillofacial trauma patients without TPF. As reported in the literature, the majority of symptoms usually subside in these patients2. However, persistent EAC edema, pain in the auricular or pre-auricular region, and trismus should increase suspicion of TPF in maxillofacial trauma patients, as these symptoms can progress to grave consequences. Persistent edema of the EAC could lead to stenosis and cause permanent hearing impairment10. Similarly, persistent trismus is an important observation in TPF cases and can lead to chronic TMD. Trismus after maxillofacial trauma is otherwise common and could be due to actual bony fractures, direct muscle injury, indirect muscle spasm, and TMJ injury2. However, in patients with TPF, injury to soft tissue of the TMJ can cause retrodiscal tissue inflammation, which can lead to temporomandibular disorders (TMD)210. Persistent TMD can be an underlying cause of trismus and pain in TPF patients. Therefore, all maxillofacial trauma cases should be thoroughly evaluated for persistent hypoacusis, trismus, and pain in the auricular or pre-auricular region because these specific observations could be an important diagnostic tool for TPF. Ear bleeding is another common clinical observation of TPF, which could also be observed in patients with skull base fracture, anterior wall auditory canal laceration16, or tympanic membrane rupture14.

Sensation of disocclusion of the affected side can also be present in TPFs. Gomes et al.2 reported this observation in an isolated case of right TPF. A possible explanation for disocclusion is pain on impingement of the condyle against the inflamed and edematous retrodiscal tissue on occluding and lateral excursion movements2. The cases in this study did not report this type of sensation but did report pain during jaw movements. Psimopoulou et al.15 and Chong and Fan1 reported TPF following mandibular trauma. The studies conducted by Altay et al.17 and Wood et al.10 reported a similar prevalence of 58% of TPF following mandibular and temporal bone fractures. These studies also insinuate that the presence of condylar fracture should increase suspicion of TPF and be detected using high resolution CT of the temporal bone1017. Although TPF is usually associated with high intensity trauma, its relationship to low intensity trauma cannot be ruled out. Thor et al.18 reported a case of TPF following an unfavorable chewing experience. Similarly, Kim et al.13 reported isolated TPF following lower molar extraction.

These cases further illustrate similarities with previously reported isolated cases of TPF. The exact number of isolated TPF cases could not be procured because of under reporting and diagnostic uncertainty in the literature, which might be due to lack of knowledge and negligence. Second, studies on the frequency of TPF are performed either in cases of temporal bone trauma or mandibular bone fracture, which, again, restrict the trauma population only to such cases. Therefore, the majority of TPF has been reported in association with mandibular fractures or temporal bone fractures or other mid-face fractures1236101517. Additional studies, with consideration of all maxillofacial trauma patients, are required in order to prevent overlooking isolated cases of TPF.

In the literature, TPF has been usually diagnosed using CT1231017. However, similar to CT, CBCT allows 3D evaluation of the facial bony structures, with the additional advantages of high spatial resolution, minimum radiation exposure, and minimum slice thickness of 0.2 mm, enabling fine structure and fracture detection19. A recent study showed that temporal bone and tympanic plates could be very well visualized on CBCT, similar to CT19. Thus, considering the advantages, CBCT could be used to detect fine fractures in maxillofacial trauma cases, including TPF.

Isolated cases of TPFs are usually treated symptomatically. For cases with trismus symptomatic treatment of TMD are given. Analgesics with anti-inflammatory properties are given in combination with proteolytic enzymes, such as serratiopeptidase, and rest of the jaw is advised until the pain subsides. This is then followed by physiotherapy to restore normal function20. EAC hemorrhage usually resolves with time and requires no active treatment. Edema in the EAC is treated with analgesics and enzymes, as previously mentioned for TMD. Follow-up is necessary for further monitoring, and patients should immediately be referred to otologists is bleeding, edema, or hypoacusis persists20. Occlusal splints can be helpful in severe pain conditions.

Currently, there are no specific classifications for TPF. In the cases reported in this study, TPFs were horizontally oriented to the sagittal plane. Due to the limited number of cases, classification of isolated TPF with respect to type or shape is not currently possible. However, studies with a larger sample or case series can help develop a classification system. Similarly, classifying isolated TPF could help with predicting trauma associated with complications or any changes in treatment plans, if required.

In conclusion, in patients with history of trauma, hemotympanum, pain in the auricular or preauricular region, and no evidence of facture involving the mandible or mid face region, prompt suspicion of TPF is necessary. Early detection and treatment are warranted because these cases have potential for serious complications.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Chong VF, Fan YF. Technical report. External auditory canal fracture secondary to mandibular trauma. Clin Radiol. 2000; 55:714–716.

2. Gomes MB, Guimarães SM, Filho RG, Neves AC. Traumatic fractures of the tympanic plate: a literature review and case report. Cranio. 2007; 25:134–137.

3. Conover GL, Crammond RJ. Tympanic plate fracture from mandibular trauma. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1985; 43:292–294.

4. Andrade Filho EF, Fadul Junior R, Azevedo RA, Rocha MA, Santos Rd, Toledo SR, et al. Mandibular fractures: analysis of 166 cases. Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992). 2000; 46:272–276.

5. Rappaport NH, Scholl PD, Harris JH Jr. Injury to the glenoid fossa. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1986; 77:304–308.

6. Copenhaver RH, Dennis MJ, Kloppedal E, Edwards DB, Scheffer RB. Fracture of the glenoid fossa and dislocation of the mandibular condyle into the middle cranial fossa. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1985; 43:974–977.

7. Pepper L, Zide MF. Mandibular condyle fracture and dislocation into the middle cranial fossa. Int J Oral Surg. 1985; 14:278–283.

8. Loh FC, Tan KB, Tan KK. Auditory canal haemorrhage following mandibular condylar fracture. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1991; 29:12–13.

9. Harwood-Nash DC. Fractures of the petrous and tympanic parts of the temporal bone in children: a tomographic study of 35 cases. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1970; 110:598–607.

10. Wood CP, Hunt CH, Bergen DC, Carlson ML, Diehn FE, Schwartz KM, et al. Tympanic plate fractures in temporal bone trauma: prevalence and associated injuries. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2014; 35:186–190.

11. Zayas JO, Feliciano YZ, Hadley CR, Gomez AA, Vidal JA. Temporal bone trauma and the role of multidetector CT in the emergency department. Radiographics. 2011; 31:1741–1755.

12. Brodie HA, Thompson TC. Management of complications from 820 temporal bone fractures. Am J Otol. 1997; 18:188–197.

13. Kim YH, Kim MK, Kang SH. Anterior tympanic plate fracture following extraction of the lower molar. J Korean Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2016; 42:51–54.

14. Antoniades K, Karakasis D, Daggilas A. Posterior dislocation of mandibular condyle into external auditory canal. A case report. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1992; 21:212–214.

15. Psimopoulou M, Antoniades K, Magoudi D, Karakasis D. Tympanic plate fracture following mandibular trauma. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 1997; 26:344–346.

16. Goldberg MH, Aslanian R, Wright J, Marco W. Auditory canal hemorrhage--a sign of mandibular trauma: report of cases. J Oral Surg. 1971; 29:425–427.

17. Altay C, Erdoğan N, Batkı O, Eren E, Altay S, Karasu S, et al. Isolated tympanic plate fracture frequency and its relationship to mandibular trauma. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2014; 65:360–365.

18. Thor A, Birring E, Leiggener C. Fracture of the tympanic plate with soft tissue extension into the auditory canal resulting from an unfavorable chewing experience. Dent Traumatol. 2010; 26:112–114.

19. Dahmani-Causse M, Marx M, Deguine O, Fraysse B, Lepage B, Escudé B. Morphologic examination of the temporal bone by cone beam computed tomography: comparison with multislice helical computed tomography. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2011; 128:230–235.

20. Okeson JP. Management of temporomandibular disorders and occlusion. 7th ed. St. Louis: Elsevier;2012.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download