Abstract

Actinomycosis is an infrequent chronic infection regarded as the most misdiagnosed disease by experienced clinicians. The Office of Rare Diseases at the National Institute of Health has also listed this disease as a “rare disease.” This article presents a case report of actinomycosis of the alveolus with unusual clinical features but a successful resolution. It also states the importance of biopsy of deceptive inflammatory lesions that do not respond or recur after conventional treatment modalities.

Go to :

Actinomyces, a saprophytic component of the endogenous flora of the oral cavity, cause a suppurative, granulomatous inflammatory lesion that is locally aggressive and destructive. This infection is anatomically and clinically divided into three types; cervicofacial, pulmonary, and abdominalpelvic, with the first being the most common form. The microbiological picture reveals that this bacterium is non-acid fast, anaerobic, and microphilic with filamentous branching and lives as a commensal in the human body but acts aggressively when it invades the mucosal barrier and enters the subcutaneous tissue. This infection is extremely unusual in the oral mucosal membranes; when present, patients exhibit classical symptoms of abscesses, sinus tract formation, and woody fibrosis. Bacteria of this genus include almost 30 species; actinomyces israelii is the most prevalent species isolated in humans. Clinical features include its peak incidence in the fourth and fifth decades of life and male predilection with superimposition in immunocompromised individuals. Cultures and pathology are keystones of the diagnosis of this disease. Specific preventive measures along with a long-term antibiotic regime are the standard line of treatment123456.

Go to :

A 35-year-old male patient who was a farmer by occupation presented to a private clinic with a chief complaint of pain in his lower left back tooth region of the jaw and numbness in the chin for the past five days. He started having pain due to grossly decayed teeth in the left lower back tooth region, for which he underwent extraction of the lower left second premolar and the first molar. A gauze pack that had been placed in the socket post-extraction had been mistakenly left in place by the patient for one week. The patient experienced dull pain in the same region; he was prescribed broad-spectrum antibiotics, but the pain persisted. He returned to the clinic with excruciating pain in the same region and numbness in his chin for the previous five days. His past medical history was non-contributory. The patient had been a chronic smoker for the last 10 years.

Upon extraoral examination, all findings were normal except for non-tender, enlarged lymph nodes. On intraoral examination of the area of the chief complaint, the unhealed extraction socket was found to be filled with slough and debris and showed exposed buccal and lingual cortices. The adjacent tooth displayed gingival recession and inflammation. Palpation revealed that the lesional area was tender, and the pain intensity was high. There was no sinus tract formation.(Fig. 1) Radiographic and blood investigations were carried out. The blood report revealed an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and leukocytosis. The radiographic interpretation showed a well-circumscribed radiolucent area surrounded by a sclerotic border extending from the distal aspect of the first premolar to the mesial aspect of the second molar. There was no effect on the surrounding teeth. No root resorption was evident.(Fig. 2) Based on the clinical and radiological evidence, a diagnosis of osteomyelitis was made. Sequestrectomy and decortications of the region were done intraorally under local anesthesia. The surgical site was thoroughly irrigated with saline, hydrogen peroxide, and betadine. Primary closure was carried out using 3-0 vicryl suture. The tissue was sent for histopathological examination.

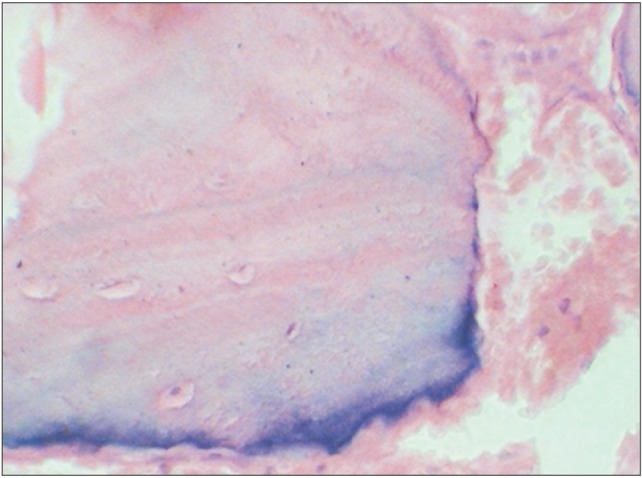

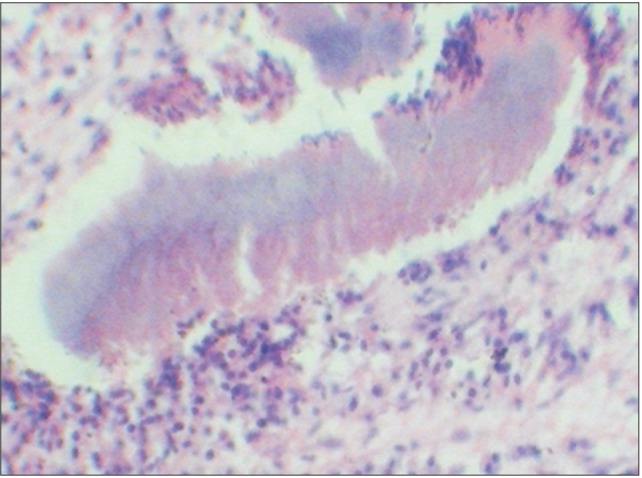

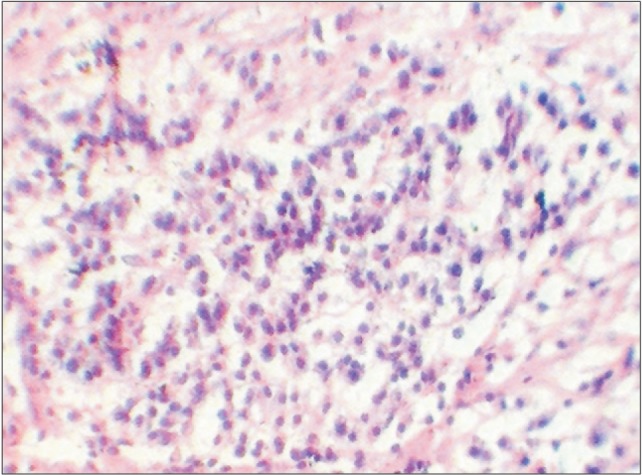

Upon histopathological assessment, the H&E-stained section showed the presence of bone and connective tissue components with dense and diffuse inflammatory cell infiltration. (Fig. 3, 4) Some basophilic areas were seen; when viewed under higher magnification, they revealed a single colony of bacteria with central basophilic filamentous sulfur granules surrounded by eosinophilic material, suggestive of actinomycotic infection.(Fig. 5, 6) Therefore, a final diagnosis of actinomycotic osteomyelitis of the alveolus was made. To substantiate the histopathological diagnosis, a special stain for actinomyces was done, which contained black filamentous areas that were positive for actinomyces.(Fig. 7)

Go to :

The presenting symptoms of pain and numbness in an unhealed extraction socket filled with slough and debris and showing exposed buccal and lingual cortices suggested a clinical diagnosis of dry socket. However, the radiographic assessment of a radioluceny surrounded by a sclerotic border indicated osteomylelitis. When such biopsied tissue is assessed histologically, a rare disease caused by one of a group of opportunistic but otherwise harmless commensals that can be complicated by one or more of another group of co-pathogens can occur. This deceptive presentation can be typical of actinomyces. This infection is extremely rare in the oral mucosal membranes; when present, patients exhibit classical symptoms of abscesses, sinus tract formation, and woody fibrosis. Sulfur granules are considered to be indicative of actinomycotic infection, but were not demonstrated in our case. The established clinical findings and history of infection in our patient did not allow us to perform a laboratory culture. Instead, the decorticated tissue was sent for histopathological appraisal. The microscopic round to oval lobulated basophilic structures surrounded by eosinophilic material produced a club-shaped appearance (termed the Splendore-Hoeppli phenomenon) that suggested actinomycosis7. These bodies are formed as a result of an antigen-antibody reaction in the inflammatory cells that predominantly include polymorphonuclear cells and granulation tissue8. The presence of an eosinophilic fringe in the advanced stage indicates the presence of certain arginine-rich proteins. The asteroid bodies seen on a background of lymphoplasmocytic infiltration in this case likely demonstrate a delayed antibody response to carbohydrate antigens78.(Fig. 3, 4) The literature suggests that high doses of intravenous penicillin G over two to six weeks followed by oral penicillin V is the ideal treatment for all forms of actinomyces9. However, a retrospective analysis and review provided by Moghimi et al.10 indicates that the combination therapy of intravenous penicillin and metronidazole while awaiting clinical improvement, followed by oral antibiotics for two to four weeks is very effective. The same treatment stratagem was adopted in the present case and provided satisfactory results.

The rarities of the case include the following: (1) missing diagnostic clinical features like abscess, sinus tract formation, and sulfur granules; (2) an immunocompetent patient with no significant medical history; and (3) involvement of a limited site confined to the alveolus and accompanied by cervicofacial disease.

In conclusion, the literature review of varied clinical reports submitted for actinomyces suggests that it is an undisruptive commensal of the oral cavity that can become pathological when superadded by periodontal disease and poor oral hygiene. Patients develop this infection when the mucosal barrier is disrupted by any predisposing factor (plaque, calculus, or periodontitis in the case of oral infection)9. The expected clinical picture is the exhibition of abscess, a draining sinus, and sulfur granules, which were not present in our case. The aim of this report was therefore to state that, in the absence of classical symptoms, actinomycosis is a diagnosis of exclusion; histopathology is the most reliable and thus the gold standard for the definitive diagnosis of actinomycotic infection. It is a rare and often severe disease when the diagnosis is missed; inadequate treatment leads to substantial morbidity and mortality. Clinicians should be aware of the possibility of actinomycosis and the importance of bone biopsy in arriving at a definitive and timely diagnosis.

Go to :

References

1. Crossman T, Herold J. Actinomycosis of the maxilla: a case report of a rare oral infection presenting in general dental practice. Br Dent J. 2009; 206:201–202. PMID: 19247335.

2. Boyanova L, Sabov R, Kolarov R, Mitov I. Chronic odontogenic osteomyelitis and facial actinomycosis of six month duration. JMM Case Rep. 2014; DOI: 10.1099/jmmcr.0.000729.

4. Sakallioğlu U, Açikgöz G, Kirtiloğlu T, Karagöz F. Rare lesions of the oral cavity: case report of an actinomycotic lesion limited to the gingiva. J Oral Sci. 2003; 45:39–42. PMID: 12816363.

5. Rathnaprabhu V, Rajesh R, Sunitha M. Intraoral actinomycotic lesion: a case report. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2003; 21:144–146. PMID: 14765614.

6. Valour F, Sénéchal A, Dupieux C, Karsenty J, Lustig S, Breton P, et al. Actinomycosis: etiology, clinical features, diagnosis, treatment, and management. Infect Drug Resist. 2014; 7:183–197. PMID: 25045274.

7. Yadegarynia D, Merza MA, Sali S, Firuzkuhi AG. A rare case presentation of oral actinomycosis. Int J Mycobacteriol. 2013; 2:187–189. PMID: 26785990.

8. Gupta N, Ahmed MBR, Jadhav K. Deceptive lesion in the palate: a case report. Indian J Multidis Dent. 2013; 4:880–883.

9. Behbehani MJ, Heeley JD, Jordan HV. Comparative histopathology of lesions produced by Actinomyces israelii, Actinomyces naeslundii, and Actinomyces viscosus in mice. Am J Pathol. 1983; 110:267–274. PMID: 6829706.

10. Moghimi M, Salentijn E, Debets-Ossenkop Y, Karagozoglu KH, Forouzanfar T. Treatment of cervicofacial actinomycosis: a report of 19 cases and review of literature. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2013; 18:e627–e632. PMID: 23722146.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download