Abstract

Objectives

The aim of this study was to compare the quality of life (QoL) of parents/caregivers of children with cleft lip and/or palate before and after surgical repair of an orofacial cleft.

Materials and Methods

Families of subjects who required either primary or secondary orofacial cleft repair who satisfied the inclusion criteria were recruited. A preoperative and postoperative health-related QoL questionnaire, the ‘Impact on Family Scale’ (IOFS), was applied in order to detect the subjectively perceived QoL in the affected family before and after surgical intervention. The mean pre- and postoperative total scores were compared using paired t-test. Pre- and postoperative mean scores were also compared across the 5 domains of the IOFS.

Results

The proportion of families whose QoL was affected before surgery was 95.7%. The domains with the greatest impact preoperatively were the financial domain and social domains. Families having children with bilateral cleft lip showed QoL effects mostly in the social domain and 'impact on sibling' domain. Postoperatively, the mean total QoL score was significantly lower than the mean preoperative QoL score, indicating significant improvement in QoL (P<0.001). The mean postoperative QoL score was also significantly lower than the mean preoperative QoL score in all domains. Only 3.2% of the families reported affectation of their QoL after surgery. The domains of mastery (61.3%) with a mean of 7.4±1.8 and finance (45.1%) with a mean score of 7.2±1.6 were those showing the greatest postoperative impact. The proportion of families whose QoL was affected by orofacial cleft was markedly different after treatment (95.7% preoperative and 3.2% postoperative).

Health is a state of physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity1. Based on this concept, it has been argued that measuring health should not be confined to the use of exclusively clinical normative indicators12. Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) measures are increasingly being used to evaluate dimensions of health, such as psychological and social aspects, that are not assessed by other measures2. Quality of life (QoL) is increasingly recognized as an important health outcome in people with surgically treatable conditions3. QoL refers to a patient's appraisal of, and satisfaction with, his or her current level of functioning compared with a perceived ideal4.

Orofacial clefts (OFCs) are the most common orofacial congenital malformations among live births, accounting for 65% of all head and neck anomalies5. Depending on geographic ancestry, OFCs affect about 1 in 500 (Asian or Amerindian ancestry) to 2,500 births (African ancestry)6. OFCs are thought to result from a complex interplay of genetic and environmental factors57. In general, Asian and Native American populations have the highest reported birth prevalence rates of OFCs, often as high as 1/500, European populations have prevalence rates at about 1/1,000, and African populations are reported to have the lowest prevalence rates at about 1/2,50067. The management of cleft lip and palate (CLP) is multidisciplinary, involving both surgical and non-surgical specialities89. Surgical reconstruction of OFCs is a common procedure carried out by oral and maxillofacial surgeons and other surgical specialists and involves surgical repair of both the lip and palate. Several techniques have been described in the literature for the repair of CLP910. This involves the repair of the lip when the child is around 3 months of age and the primary palate any time between 6-14 months of age910.

OFCs might affect family functioning and probably reduce the QoL in school-age children and their parents11. Children with OFCs might have to tolerate psychosocial disadvantages due to their altered speech and facial appearance, probably affecting their QoL and family functioning11. Kramer et al.11 reported that the occurrence of OFC is a source of considerable shock to the parents of an affected baby. The impact of having CLP is of particular interest in sub-Sahara Africa, where cultural beliefs contribute to psycho-social instability and infanticide1213. OFC is reported not to be a major cause of mortality in developed countries; however, OFC causes considerable morbidity to affected children and imposes a substantial financial risk for families, with a concomitant societal burden11. Thus, this study was designed to compare the QoL of families of children with cleft lip and/or palate before and after surgical repair.

The study was a prospective longitudinal study to compare the QoL outcome in parents/caregivers of children with cleft lip and/or palate before and after surgical interventions. It was conducted at the Department of Oral/Maxillofacial Surgery of Lagos University Teaching Hospital, Lagos, Nigeria between 2012 and 2014. Approval for the study was obtained from the Health Research and Ethics Committee of Lagos University Teaching Hospital.

Written informed consent was obtained from the parents/caregiver of each subject before enrollment in the study. Prior to this, detailed information and explanations of the study were given to each parent or guardian. Parents/guardians were also allowed to ask questions and clarifications during the consent process. Opportunity to withdraw at any stage of the study without victimization or denial of treatment was made known to each parent or caregiver.

Parents/caregivers of children born with non-syndromic cleft lip and/or palate and who needed surgical treatment to correct the defects were included in the study. Parents/caregivers of the children with syndromic clefts and oblique facial clefts were excluded from this study. Ultimately, parents/caregivers of 94 subjects who required either primary or secondary OFC repair and who satisfied the inclusion criteria were recruited.

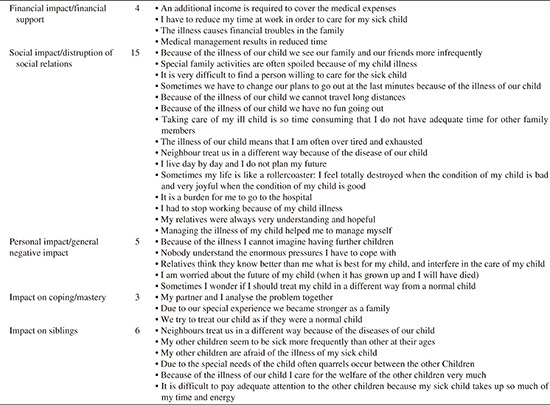

The following preoperative data were collected and recorded in a proforma for each subject; age and sex of patient, type of cleft defects (lip and/or palate), type of cleft repair (lip or palate), and surgical technique. CLP were classified according to Kernahan and Stark in 195814. A preoperative HRQoL questionnaire (Appendix 1) was administered to the parents/caregivers of each subject at least one week before surgery. This instrument, ‘Impact on Family Scale’ (IOFS)1516, was applied in order to detect the subjectively perceived QoL in the affected family. The IOFS was developed in the Anglo-American literature as a self-report instrument to measure the effects of chronic conditions and disability in childhood on the family. It consists of 33 items related to five dimensions (Appendix 1), comprising financial impacts (4 items), social relationships (15 items), personal impacts (5 items), coping strategies (3 items), and concerns of siblings (if present; 6 items). The parents are asked to indicate if the item was ‘absolutely true,’ ‘true in most aspects,’ ‘not true in most aspects,’ or ‘not true at all’. A total impact score was calculated by summing the scores of all items. The minimum total score possible was 33, and the maximum total score possible was 132. Scores of 1-66 indicated that the QoL was not affected, while any score greater than 66 indicated that the QoL was affected. Postoperatively, the same HRQoL questionnaire (Appendix 1) was administered to each parent/caregiver at least 2 months after surgical repair. Data was analyzed using SPSS for Windows (version 17.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Data are presented in the form of tables. Other descriptive and inferential statistics were used as appropriate. The mean pre- and postoperative total scores were compared using paired t-test. Pre- and postoperative mean scores were also compared across the 5 domains of the IOFS. For all comparisons, P<0.05 was adopted as the criterion for establishing statistical significance.

Family of 95 children with OFC and who satisfied the inclusion criteria and consented to participate in the study were recruited. One family, however, decided to discontinue prethe study midway for personal reasons, and their data were excluded from the study. Thus, 94 out of the 95 families recruited were available for final analysis.

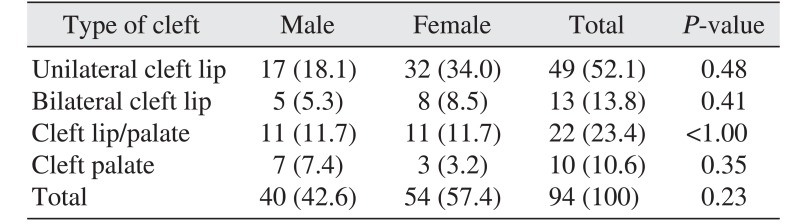

The most common type of OFC was unilateral cleft lip (52.1%), followed by cleft lip/palate (23.4%) and bilateral cleft lip (13.8%).(Table 1) There was no statistically significant difference in the pattern of cleft distribution between males and females (P=0.179). The mean age of subjects with OFC was 5.7±8.5 months, ranging between 1 and 48 months. A majority (78.0%) of the subjects presented between one month and 12 months of age, and most of these were within a 3-month age bracket. Of these, 54 were females and 40 were males, with a female-to-male ratio of 1.4:1.

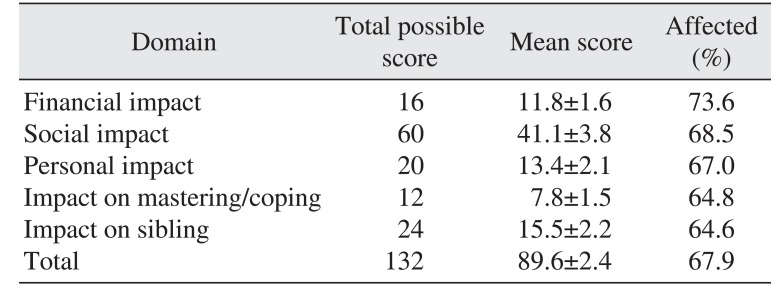

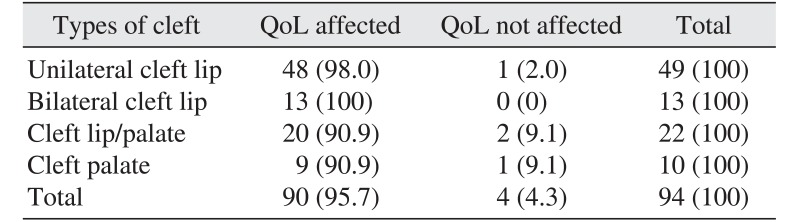

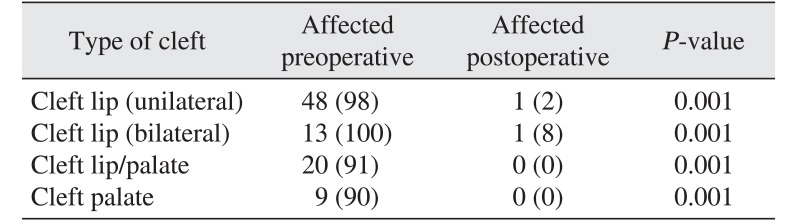

The mean preoperative total QoL score for the families was 89.6±2.4. The proportion of families whose QoL was affected was 95.7%. The domains with the greatest impact were the financial domain with a mean score of 11.8±1.6 and the social domain with a score of 41.1±3.8; these domains were affected in 73.6% and 68.5% of families, respectively. (Table 2) Table 3 compares the proportion (%) of families whose QoL was affected before surgery according to type of OFC. The families of children with bilateral cleft lip were most affected, as all of them (100%) indicated that their QoL was affected preoperatively, closely followed by families of those who had unilateral cleft lip (98.0%).

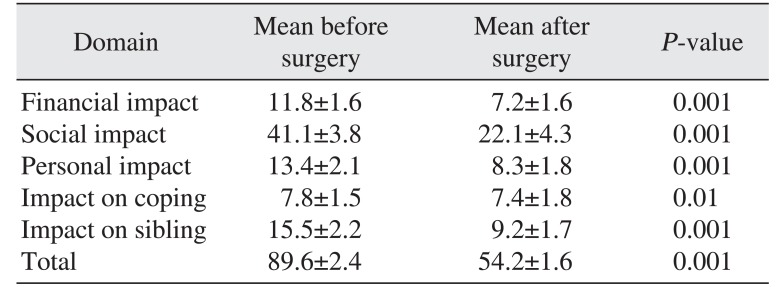

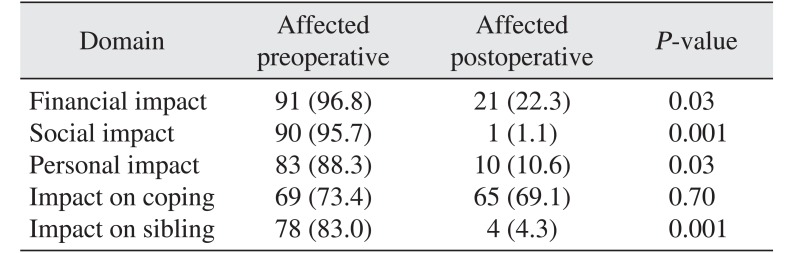

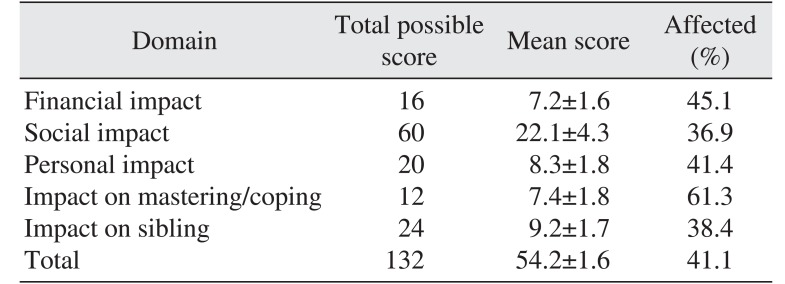

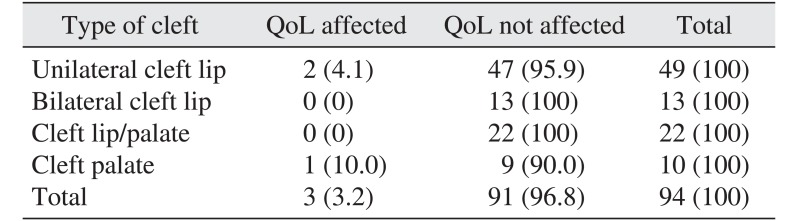

The mean total QoL score for the families after surgery was 54.2±1.6, which was significantly lower than the mean preoperative QoL score, indicating significant improvement in QoL (P<0.001). Table 4 compares the mean QoL before and after surgery in each domain. There was significant improvement in all domains after surgery.(Table 4) The smallest difference between pre- and postoperative periods was noted in “impact on coping/mastering” domain.(Table 4) After surgery, only 3.2% of the families indicated that their QoL was affected, in contrast with 95.7% who indicated an effect before surgery (P=0.001). Table 5 compares the proportion of families whose QoL was affected between pre- and postoperative periods in each domain. A statistically significant difference was observed in all domains except “impact on coping domain.” The domains of coping/mastering with a mean of 7.4±1.8 and finance with a mean score of 7.2±1.6, with 61.3% and 45.1% of families QoL affected, respectively, showed the greatest impact after surgery.(Table 6) In addition, 10.0% of families of children with cleft palate reported that their QoL was affected after surgical intervention, while only 4.1% of families of subjects with unilateral cleft lip reported an effect on QoL. No members of families of children with bilateral cleft lip or those with CLP reported affectation of their QoL after surgical intervention.(Table 7)

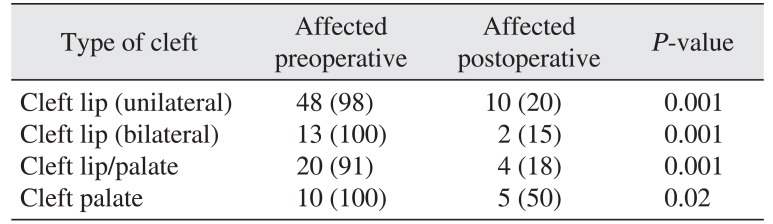

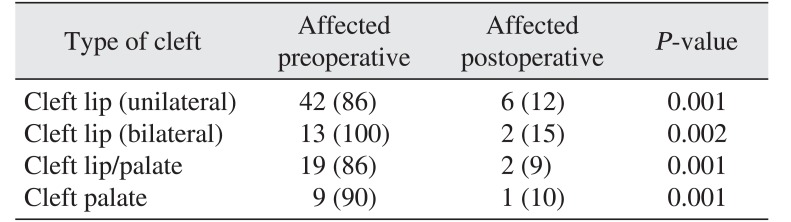

Before surgery, all families of children with bilateral cleft lip and cleft palate (100%) reported that their finances were negatively impacted by caring for the cleft children. However, after surgery, only 15% of them reported deterioration in financial capacity.(Table 8) Overall, there was a statistically significant improvement in family financial status after surgery for all different types of OFC.(Table 8)

Before surgical intervention, all families of children with bilateral cleft lip (100%) reported that caring for their cleft child negatively impacted their social life.(Table 9) After surgical intervention, however, only one family indicated that caring for their child negatively impacted their social life. This was not much different from the report of the families living with children with unilateral cleft lip.(Table 9) Overall, there was statistically significant improvement in the social lives of the families with cleft children after surgery.(Table 9)

Table 10 shows changes in the proportion of affected families in the personal impact domain before and after surgery in relation to type of cleft. All families of children with bilateral cleft lip reported that caring for the cleft child greatly negatively affected their QoL before surgery; however, only two families in this category reported such an effect following surgical intervention.(Table 10) In addition, 90% of the families of children with cleft palate reported that caring for their cleft child negatively affected their personal life, but no family in this category reported such an effect after surgery. (Table 11) Overall, surgical intervention was associated with a statistically significant reduction in the proportion of families who reported “affected” in the personal impact domain. (Table 10)

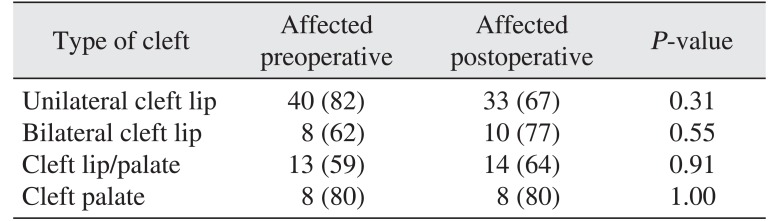

Before surgery, 82% of the families of the children with unilateral cleft lip reported that caring for a child with cleft negatively affected their coping ability. This value only decreased to 67% after surgical intervention.(Table 11) Notably, a higher proportion of families of children with bilateral cleft lip and those with cleft lip/palate reported that their QoL was affected after surgery than before surgery.(Table 11)

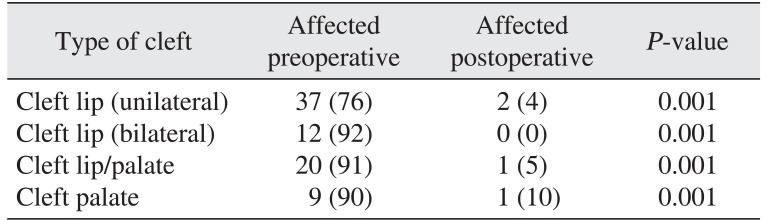

Before surgery, almost all families of children with OFC reported that caring for the child with OFC had a negative impact on the sibling. This impact was smallest for unilateral cleft lip (76%). However, after surgery, there was a statistically significant reduction in the proportion of families who reported that caring for a child with OFC had a negative impact on the siblings.(Table 12)

In the present study, the most common type of OFC was unilateral cleft lip (52.1%), followed by cleft lip/palate (23.4%) and bilateral cleft lip (13.8%). This finding is in agreement with that of Donkor et al.17 who reported unilateral cleft lip as the most common type of OFC in Ghana. A previous study18 from Nigeria also corroborated our findings that unilateral cleft of the lip is the most common type. Onah et al.19 also reported cleft lip as the most common type, at 41% in their study. There were some African studies that suggested that CLP is the most common type, contrary to the present study2021. Most Caucasian studies, however, reported CLP to be the most common type of OFC52223.

Caring for a child with OFC can result in decreased QoL for parents and caregivers24. It has been reported that affected families might have to compensate for increased financial, social, and personal impacts before primary treatment is completed25. OFC might also affect family functioning and probably decreases QoL in school-age children and their parents11. OFC is also reported to be associated with several health problems including complications early in life such as problems with feeding or ear infections26, which can result in significant morbidity risks and also increased mortality risks, especially in less developed settings where early systematic pediatric care might not be commonly accessible26. Several of the effects of OFC are reported to extend through adulthood, resulting in increased mortality and morbidity2627.

Most of the few publications on the QoL of families with children with cleft lip/palate focused on the impact of OFC on the family without necessarily considering the effect of surgical intervention on QoL1126. The present study focuses on the effect of surgical intervention on QoL of family/caregivers of children with CLP.

In the present study, the mean preoperative total QoL score as well as the proportion of families whose QoL was affected preoperatively were high, indicating decreased QoL in families/caregivers of children with OFC. The findings suggest that caring for a child with cleft lip/palate can have a negative impact on the QoL of the family.

The domains with the greatest impact were the financial domain and social domains. Among those affected, the families of children with bilateral cleft lip were most affected, closely followed by families of those who had unilateral cleft lip. Isolated cleft palate had the smallest impact on the families before surgical intervention. This is in contrast to a study by Weigl et al.28, who employed a Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) to determine HRQoL of mothers of children with CLP. Weigl et al.28 reported that mothers of patients with CLP displayed better HRQoL than controls in the domains of personal functioning, body pain, and general health. The difference in the result of our study and that by Weigl et al.28 can be explained by the following. Weigl et al.28 used the SF-36, which ultimately is a measure of health status as opposed to being a measure of QoL, and used only the mother to represent a family, in addition to the different societal values between Germany and Nigeria. The quality and cost of care between a developed economy like Germany with a robust health insurance system29 and a developing economy like Nigeria where health insurance is not well developed30 can also explain the contradicting results. Our study does agree with the studies by Kramer et al.25 and Hunt et al.31, who found relatively small impacts on all dimensions for parents of children with CLP aged between 6-24 months. Specifically, impacts were most evident on the dimensions of coping and personal impact32. In agreement with the present study, Kramer et al.11 also found that parents of children with CLP reported less impact on QoL as assessed by the IOFS than parents of children with only cleft lip or palate. The domains mostly affected in our study were social relationship, sibling, and finance. This is understandable considering that many children with CLP have a less attractive facial appearance or speech than their peers. A high incidence of teasing over facial appearance is reported among those with CLP31. In some African societies, children born with OFC are viewed as a curse and the family, especially the mothers, as witches. In many cases, such a mother is abandoned by her husband, family, and friends. This could explain why the societal relationship and sibling domains are mostly affected. Caring for a child with OFC often involves frequent hospital visits, with associated loss of work hours, out of pocket financing of health care services, and often loss of job due to frequent time away. All of these factors can help explain the high level of financial impact noted in our study.

Surgery is a major factor influencing QoL in the early stages of CLP3334. In an earlier study34, in which 175 sets of parents were interviewed, both mothers and fathers placed repair of the cleft as an important concern in OFC management. Surgery was seen as the solution to the cleft, as parents showed prospective feelings of ‘everything being well’ following surgery34. Surgery is also a source of significant concern for parents, especially as the date of surgery approaches35. Worries related to the procedure have included timing of the procedure, duration and recovery, side effects, the care involved, whether additional tissue was required for the repair, techniques used, outcomes of surgery, and pain3436.

In the present study, the mean total QoL score following surgical intervention was found to be significantly lower than before surgery, indicating that surgical intervention significantly improved the QoL of the parents. Of all subjects, only three experienced negatively affected QoL after surgical intervention. The effect of surgery was most notable in the social and personal domains. This drastic change in QoL of parents following surgical intervention might be associated with relief of the enormous amount of physical, financial, psychological, and emotional stress associated with caring for children with OFC. An earlier study reported that both mothers and fathers placed repair of the cleft as an important concern after receiving the diagnosis34. Before surgery, the total impact was highest in families having children with bilateral cleft lip; after surgery, the families having children with isolated cleft palate reported the highest impact. Cleft palate is repaired much later than cleft lip; therefore, the stress of prolonged clinic appointments and the challenges associated with breakdown of cleft palate and subsequent surgeries could account for the highest impact in families with isolated cleft palate. In addition to this, the need for speech therapy appointments could also add to stress of parents in isolated cleft palate cases.

Caring for a child with OFC greatly impacts the financial life of the family. In a previous study37, it was reported that average home health expenditure per child with OFC was 45 times higher than for a child without cleft. It was also reported that expenditure per child with OFC was $22,642 compared to $3,900 for an unaffected child37. Mean expenditure for a child with cleft palate or child with cleft lip and cleft palate was reported to be about three times higher than for a child with cleft lip alone. Morris and Tharp38 conducted a survey about the present economic aspects of CLP treatment. In their study, they estimated that, on a fee-for-service basis, treatment cost could be as high as $30,000 for one patient, not including such indirect costs as travel costs, loss of wages, and added child care38. In the present study, before surgery, all families of children with bilateral cleft lip and cleft palate (100%) reported that their finances were negatively impacted by caring for the cleft children. After surgery, however, only 15% of these families reported deterioration in their financial capacities.

A difference in appearance is perhaps the most obvious consequence of CLP, with many families believing that surgery will make their child's life better through the changes in appearance. Change in appearance as a result of OFC can also affect the bonding relationship between parent and child. Early attachment is reported to be a reciprocal process, relying on the reactions between a primary care giver and the baby34. Before surgical intervention, 95.7% of the families in this study reported that caring for their cleft child negatively impacted their social life. Parents of children with cleft have been reported to describe their children as having more externalizing (social) behavioral problems compared with the report of parents of children without cleft31. Other studies have also reported that children with CLP tend to see their parents as having more negative feelings and worrying more3134.

Elements of coping and adjustment have been investigated in order to best understand how a family adapts to having a child with CLP313439. Surgical intervention only positively affected the coping ability of the families with children born with unilateral cleft lip in our study. The families of children with bilateral cleft lip and those with cleft lip/palate reported worsening of their coping ability following surgery, while there was no change in the coping abilities of the families with children born with isolated cleft palate. This finding agrees in part with observations of Kramer et al.25, who reported that coping problems among families of children with cleft lip (whether unilateral or bilateral) increased compared to families with children having CLP or isolated cleft palate. This finding could be explained based on the more severe impact of bilateral cleft lip and cleft lip/palate on the facial appearance of the child or to avoidant rather than problemsolving coping strategies in the parents35. Social support has been highlighted as being useful in the process of coping, as well as perceived support from professionals involved in the child's care3539. Support from friends and family has been linked to lower distress, better adjustment, and less negative family impact, possibly due to social support providing greater feelings of belonging, self-esteem, a positive outlook, and a greater sense of value39

In the present study, the postoperative data were collected at least two months after surgery. Although, the effect of surgery on QoL of families was obvious within two months after surgery, a longer period of postoperative evaluation might reveal the effect of late complications of surgery on QoL. We consider this a limitation of this study, which can be improved upon by others who intend to validate our findings.

Caring for children with OFC significantly reduces the QoL of parents/caregivers in all domains. The impact was most pronounced in financial and social domains and in those caring for children with bilateral cleft lip. However, surgical intervention significantly improved the QoL of the parents/caregivers of these children. Overall, surgical intervention had a statistically significant reduction in the negative impact of having a child with OFC in all domains except “coping ability.” Care givers of children with OFC will require support from society, health professionals, friends, and relatives. Therefore, research efforts must be geared toward designing a coping strategy for families of children born with OFC.

References

1. Preamble to the Constitution of the World Health Organization as adopted by the International Health Conference [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization;cited 2016 Oct 26. Available from: http://www.who.int/governance/eb/who_constitution_en.pdf.

2. Castro RA, Cortes MI, Leão AT, Portela MC, Souza IP, Tsakos G, et al. Child-OIDP index in Brazil: cross-cultural adaptation and validation. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2008; 6:68. PMID: 18793433.

3. Manchanda K, Sampath N, De AS, Bhardwaj VK, Fotedar S. Oral health-related quality of life- a changing revolution in dental practice. J Cranio Max Dis. 2014; 3:124–132.

4. Taillefer MC, Dupuis G, Roberge MA, LeMay S. Health-related quality of life models: systematic review of the literature. Soc Indic Res. 2003; 64:293–323.

5. Manyama M, Rolian C, Gilyoma J, Magori CC, Mjema K, Mazyala E, et al. An assessment of orofacial clefts in Tanzania. BMC Oral Health. 2011; 11:5. PMID: 21288337.

6. Dixon MJ, Marazita ML, Beaty TH, Murray JC. Cleft lip and palate: understanding genetic and environmental influences. Nat Rev Genet. 2011; 12:167–178. PMID: 21331089.

7. Wehby GL, Murray JC. Folic acid and orofacial clefts: a review of the evidence. Oral Dis. 2010; 16:11–19. PMID: 20331806.

8. Goodacre T, Swan MC. Cleft lip and palate: current management. Paediatr Child Health. 2008; 6:283–292.

9. Hodgkinson PD, Brown S, Duncan D, Grant C, McNaughton A, Thomas P, et al. Management of children with cleft lip and palate: a review describing the application of multidisciplinary team working in this condition based upon the experiences of a regional cleft lip and palate center in the United Kingdom. Fetal Matern Med Rev. 2005; 16:1–27.

10. Farronato G, Kairyte L, Giannini L, Galbiati G, Maspero C. How various surgical protocols of the unilateral cleft lip and palate influence the facial growth and possible orthodontic problems? Which is the best timing of lip, palate and alveolus repair? Literature review. Stomatologija. 2014; 16:53–60. PMID: 25209227.

11. Kramer FJ, Gruber R, Fialka F, Sinikovic B, Hahn W, Schliephake H. Quality of life in school-age children with orofacial clefts and their families. J Craniofac Surg. 2009; 20:2061–2066. PMID: 19881367.

12. Oginni FO, Asuku ME, Oladele AO, Obuekwe ON, Nnabuko RE. Knowledge and cultural beliefs about the etiology and management of orofacial clefts in Nigeria's major ethnic groups. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2010; 47:327–334. PMID: 20590456.

13. Akinmoladun VI, Owotade FJ, Afolabi AO. Bilateral transverse facial cleft as an isolated deformity: case report. Ann Afr Med. 2007; 6:39–40. PMID: 18240492.

14. Kernahan DA. The striped Y--a symbolic classification for cleft lip and palate. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1971; 47:469–470. PMID: 5574216.

15. Lawal FB, Taiwo JO, Arowojolu MO. How valid are the psychometric properties of the oral health impact profile-14 measure in adult dental patients in Ibadan, Nigeria? Ethiop J Health Sci. 2014; 24:235–242. PMID: 25183930.

16. Astrøm AN, Haugejorden O, Skaret E, Trovik TA, Klock KS. Oral Impacts on Daily Performance in Norwegian adults: validity, reliability and prevalence estimates. Eur J Oral Sci. 2005; 113:289–296. PMID: 16048520.

17. Donkor P, Plange-Rhule G, Amponsah EK. A prospective survey of patients with cleft lip and palate in Kumasi. West Afr J Med. 2007; 26:14–16. PMID: 17595984.

18. Abdurrazaq TO, Micheal AO, Lanre AW, Olugbenga OM, Akin LL. Surgical outcome and complications following cleft lip and palate repair in a teaching hospital in Nigeria. Afr J Paediatr Surg. 2013; 10:345–357. PMID: 24469486.

19. Onah II, Opara KO, Olaitan PB, Ogbonnaya IS. Cleft lip and palate repair: the experience from two West African sub-regional centres. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2008; 61:879–882. PMID: 17652050.

20. Obuekwe O, Akapata O. Pattern of cleft lip and palate [corrected] in Benin City, Nigeria. Cent Afr J Med. 2004; 50:65–69. PMID: 15881314.

21. Conway JC, Taub PJ, Kling R, Oberoi K, Doucette J, Jabs EW. Ten-year experience of more than 35,000 orofacial clefts in Africa. BMC Pediatr. 2015; 15:8. PMID: 25884320.

22. Bill J, Proff P, Bayerlein T, Weingaertner J, Fanghänel J, Reuther J. Treatment of patients with cleft lip, alveolus and palate--a short outline of history and current interdisciplinary treatment approaches. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2006; 34(Suppl 2):17–21.

23. Murray L, Hentges F, Hill J, Karpf J, Mistry B, Kreutz M, et al. The effect of cleft lip and palate, and the timing of lip repair on mother-infant interactions and infant development. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008; 49:115–123. PMID: 17979962.

24. Vella SLC, Pai NB. A systematic review of the quality of life of carers of children with cleft lip and/or palate. Int J Health Sci Res. 2012; 2:91–96.

25. Kramer FJ, Baethge C, Sinikovic B, Schliephake H. An analysis of quality of life in 130 families having small children with cleft lip/palate using the impact on family scale. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007; 36:1146–1152. PMID: 17822884.

26. Shkoukani MA, Chen M, Vong A. Cleft lip: a comprehensive review. Front Pediatr. 2013; 1:53. PMID: 24400297.

27. Hopper RA, Tse R, Smartt J, Swanson J, Kinter S. Cleft palate repair and velopharyngeal dysfunction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014; 133:852e–864e. PMID: 24352207.

28. Weigl V, Rudolph M, Eysholdt U, Rosanowski F. Anxiety, depression, and quality of life in mothers of children with cleft lip/palate. Folia Phoniatr Logop. 2005; 57:20–27. PMID: 15655338.

29. Wehby GL, Cassell CH. The impact of orofacial clefts on quality of life and healthcare use and costs. Oral Dis. 2010; 16:3–10. PMID: 19656316.

30. Adeyemo WL, Taiwo OA, Oderinu OH, Adeyemi MF, Ladeinde AL, Ogunlewe MO. Oral health-related quality of life following non-surgical (routine) tooth extraction: a pilot study. Contemp Clin Dent. 2012; 3:427–432. PMID: 23633803.

31. Hunt O, Burden D, Hepper P, Johnston C. The psychosocial effects of cleft lip and palate: a systematic review. Eur J Orthod. 2005; 27:274–285. PMID: 15947228.

32. Kramer FJ, Gruber R, Fialka F, Sinikovic B, Schliephake H. Quality of life and family functioning in children with nonsyndromic orofacial clefts at preschool ages. J Craniofac Surg. 2008; 19:580–587. PMID: 18520368.

33. Akinmoladun VI, Obimakinde OS. Team approach concept in management of oro-facial clefts: a survey of Nigerian practitioners. Head Face Med. 2009; 5:11. PMID: 19426559.

34. Fletcher AJ, Hunt J, Channon S, Hammond V. Psychological impact of repair surgery in cleft lip and palate. Int J Clinl Pediatr. 2012; 1:93–96.

35. Hasanzadeh N, Khoda MO, Jahanbin A, Vatankhah M. Coping strategies and psychological distress among mothers of patients with nonsyndromic cleft lip and palate and the family impact of this disorder. J Craniofac Surg. 2014; 25:441–445. PMID: 24481167.

36. Chuacharoen R, Ritthagol W, Hunsrisakhun J, Nilmanat K. Felt needs of parents who have a 0- to 3-month-old child with a cleft lip and palate. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2009; 46:252–257. PMID: 19642744.

37. Cassell CH, Meyer R, Daniels J. Health care expenditures among Medicaid enrolled children with and without orofacial clefts in North Carolina, 1995-2002. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2008; 82:785–794. PMID: 18985685.

38. Morris HL, Tharp R. Some economic aspects of cleft lip and palate treatment in the United States in 1974. Cleft Palate J. 1978; 15:167–175.

39. Baker SR, Owens J, Stern M, Willmot D. Coping strategies and social support in the family impact of cleft lip and palate and parents' adjustment and psychological distress. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2009; 46:229–236. PMID: 19642758.

Table 1

Sex distribution according to cleft type

Table 2

Preoperative mean score in each domain

Table 3

Quality of life (QoL) of the family before surgical intervention according to cleft type

Table 4

Comparison of the mean quality of life before and after surgery in each domain

Table 5

Comparison of proportion of families whose quality of life was affected before and after surgery according to domain

Table 6

Mean score and proportions of affected patients in each domain after surgery

Table 7

Quality of life (QoL) of the family after surgical intervention

Table 8

Types of cleft and proportions of families affected (financial impact) before and after surgery

Table 9

Types of cleft and proportions of families affected (social impact) before and after surgery

Table 10

Changes in proportions of affected families (personal impact) before and after surgery according to cleft type

Table 11

Changes in proportions of affected families (impact on coping) before and after surgery according to cleft type

Table 12

Changes in proportions of affected families (impact on sibling) before and after surgery according to cleft type

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download