I. Introduction

Square faces due to prominent mandibular angles of varying degrees are often treated with plastic surgery in modern societies where oval faces with symmetrical and small overall facial outlines are considered esthetically pleasing.

Since brachycephalic or mesocephalic faces are typical of Asians, whereas dolichocephalic faces are typical of Caucasians, reduction of mandibular angles and zygomas resulting in oval face contours is widespread among Asians

1.

Although factors leading to a prominent mandibular angle can be subdivided into 2 groups, i.e., congenital and developmental (e.g., bruxism), no exact cause has been identified so far, despite several studies

2.

Numerous studies have been conducted on the cause, since the terms, masseter muscle hypertrophy or benign masseteric hypertrophy, were coined for a prominent unilateral or bilateral mandibular angle

34, and improvement in surgical techniques have been made. Surgical corrections have been carried out since the late 1980s

5. Techniques for the reduction of a mandibular angle are classified as masseter muscle reduction and mandibular bone reduction; the latter is preferred to the former by surgeons due to its many advantages

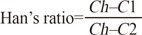

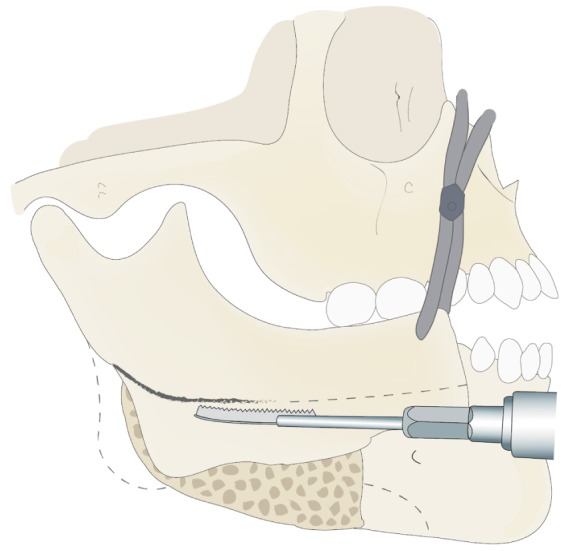

56. While curved ostectomy of the mandibular angle is by far the most widely used technique, lateral cortical ostectomy of the mandibular angle and ramus is recently gaining popularity

7. Indications, pros and cons as well as various procedures for both techniques have been described in detail.

In spite of numerous reports on the surgical technique for mandibular angle reduction, only a few studies have been conducted to evaluate patient postoperative satisfaction and esthetic improvements. Since there is a lack of established standards for the esthetic mandibular angle, the patient's request is the primary determinant in the operative plan. In other words, postoperative satisfaction and the demands of each patient are the most critical criteria in mandibular angle reduction. However, unclear understanding between the surgeon and the patients' esthetic demands may bring about unexpected outcomes. Moreover, a patient's misperception of self may lead to disappointment with the result of the treatment. Lack of standardized preoperative and postoperative assessment methods may result in such situations. Thus, an objective and systematic manner of evaluation and diagnosis is required.

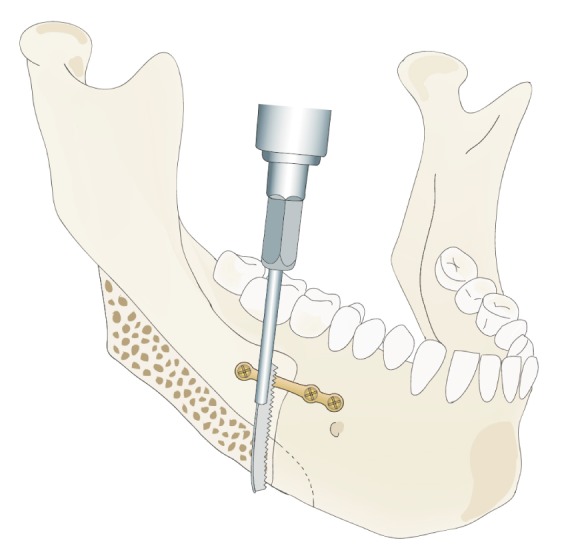

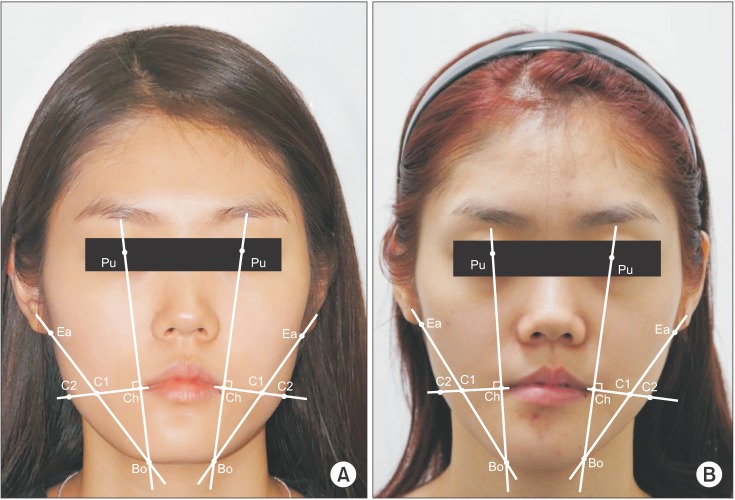

Therefore, this study was conducted to test Han's ratio as an objective and quantitative method obtained from pre- and postoperative data in patients requesting mandibular angle reduction. Considering that the outline of oval shaped mandibles resembles an inverted triangle, favorable soft tissue landmarks were determined and quantified in order to compare the amount of reduction in patients who have undergone mandibular reduction surgery

8.

IV. Discussion

A recent worldwide trend in maxillofacial reconstruction focuses on cosmetic surgeries primarily aimed at esthetic enhancement of individuals, unlike the past when the mainstream of treatment was reconstruction of facial deformities induced by malignant cancer or trauma. This is not a transient phenomenon but rather a transition owing to the demands of contemporary esthetically-minded patients. In fact, the range of surgery has been gradually broadened to meet the changing needs of patients more specifically, such as jaw and facial contouring surgery, predominantly including the correction of mandibular prognathism.

A face with a prominent mandibular angle makes a strong and masculine impression on others, so it is not preferred among Asians, including Koreans. Moreover, for genetic and racial reasons, Asians tend to have a wider lower face than Caucasians and as a result, mandibular angle reduction is more common in the East than in the West

9.

The average bigonial distance of Korean women is 117.8 to 125.25 mm whereas that of Caucasian women is 105 to 109 mm

10. Thus, a prominent mandibular angle is not a pathologic phenomenon but instead a problem that merely requires an esthetic manner of approach. Standards of beauty have historically been established respectively in western and eastern society. However, since modern times, the spread of the western centered culture worldwide has resulted in western standards of beauty dominating the East as well. When faces of 72 Korean-American women were scored by 10 other Korean-Americans using a visual analogue scale (VAS) of appearance, the highest rated were more similar to Western faces than that of the average Korean

11. In the same sense, Asians with wide a interangular dimension consider narrower bigonal distance, typical of Caucasians, charming and desire mandibular angle reduction.

Baek et al.

5 who first suggested the modern concept of mandibular angle reduction, concluded that a prominent mandibular angle is a relatively common esthetic problem and the cause lies in inferoposterior projection of the angular portion of the mandible rather than muscle hypertrophy. In addition, Legg

12 reported that the prominent angles are attributed to racial differences, with hypertrophy of the masseter muscle predominant in Caucasians and bony projection in Asians.

Improvement in surgical techniques and research of causes have continued since the introduction of terms including prominent unilateral of bilateral angle, masseter muscle hypertrophy or benign masseteric hypertrophy.

Surgical correction by an extraoral approach was initially performed by Gurney

13 with excision of the lateral portion of the hypertrophic masticatory muscle, followed by Adams

14 with skin incision and finally the first intraoral approach by Converse

15. Popular current techniques include curved ostectomy and lateral cortical ostectomy, originally introduced by Baek et al.

516 in 1989 and 1994, respectively.

In spite of many reports on surgical techniques for mandibular angle reduction, studies on preoperative diagnosis and postoperative assessment are relatively scarce.

The gonial angle is the most critical part in the profile, especially in curved ostectomy, since patients with an initially large gonial angle may show an even larger angle and thus an abnormal and unnatural contour after the procedure

7. The mean mandibular angle in Koreans is 128.71°±3.87° and the mandibular plane-sella nasion (MP-SN) is 32.69°±6.11°

1718. Meanwhile, Jin

7 insisted that mandibular ramus to body length ratio should also be considered important for profile analysis. When the length of the body is longer than that of the ramus, only a slight increase in mandibular angle brings about a very awkward appearance. Thus, enlargement of the mandibular angle is not favorable in either the case of mandibular prognathism with a long ramus length or mandibular recession with a short body length.

Since Baek et al.

16 pointed out that the frontal as well as the profile view are crucial for the diagnosis and assessment of mandibular angle, diagnosis drawn from both sides has become a general procedure

19.

Han and Kim

9 measured bitemporal, bizygomatic and bigonial distance and calculated their ratios. He reported that ideally the bitemporal and bigonial distance should be equal and narrower than the bizygomatic distance by 10%. However, this is merely a concept of linear measurement and carries some disadvantages. Ambiguous criteria for nonbiased assessment of esthetic enhancement and an inability to evaluate facial asymmetry are examples of shortcomings in the evaluation of treatment results.

Barnett and Whitaker

20 proposed a three-dimensional (3D) method for midface and lower face evaluation. Six landmarks were chosen and connected with lines and eventually constituted planes. However, this method is quite complicated and difficult to use in the clinical setting. Recently, computer-aided surgical simulation improved presurgical work-up efficiency. It also provided an opportunity to illustrate multidimensional correction at the skeletal and soft tissue levels. CT scanning images are needed for this, but due to economical and ethical issues, CT scanning images are not used every time. Instead, two-dimensional films are commonly used for post-orthognathic surgery follow-up visits. In clinical practice, there are limits to the 3D analysis of patient faces before and after operations. Therefore, in this study we suggested a simple and fast method to quantitatively analyze the differences in the pre- and postoperative mandibular angles using frontal facial photographs only.

The evaluation of facial symmetry should be carried out on the facial soft tissue of actual patients and not radiographs. Radiographic shape of bones cannot reflect real facial structure because of variation in the thickness of the masseter muscle. Moreover, it should be noted that a shorter than average bigonial distance may make a face look more beautiful

7.

As to the assessment of patient satisfaction level after treatment, only a few studies have adopted objective methods such as the VAS to estimate patient aesthetic satisfaction. Choi et al.

21 conducted a survey with 20 questions and reported that 97% of the patients who underwent mandibular reduction surgery were satisfied with the results.

In most studies, esthetic satisfaction was assessed in a subjective manner, for example satisfactory or unsatisfactory. The results revealed that a considerable number of patients were satisfied with the esthetic outcome of their operation. However, such studies may have been biased, since most were retrospective studies on the patient group and no established criteria for radiographic or clinical success existed.

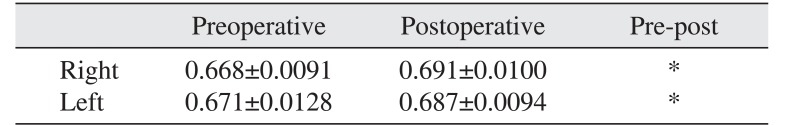

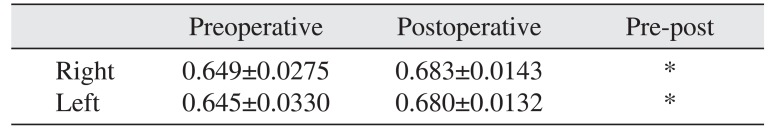

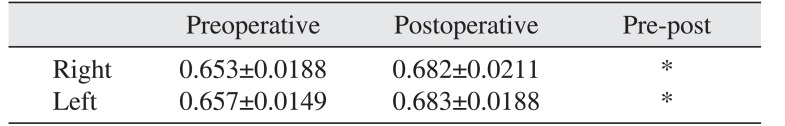

In the present study, Han's ratio was obtained and compared to evaluate postoperative esthetic enhancement in exact numerical values, rather than patient subjective satisfaction level. A Han's ratio of approximately 1.0 indicates a more oval shaped lower face line. Although the standard of beauty is obviously a subjective notion, 82 winners of Korean beauty pageants from 2002 to 2011 can be presumed to represent the recent standard of beauty in Korea. Han's ratio was measured in their frontal facial photos and the mean values were 0.688 on the right and 0.696 on the left.

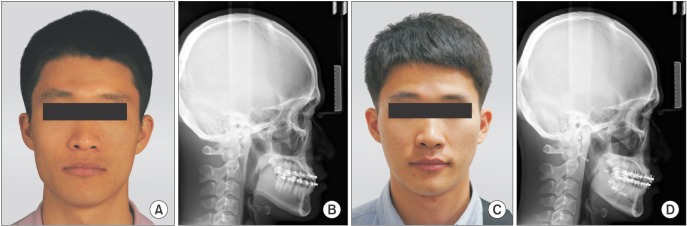

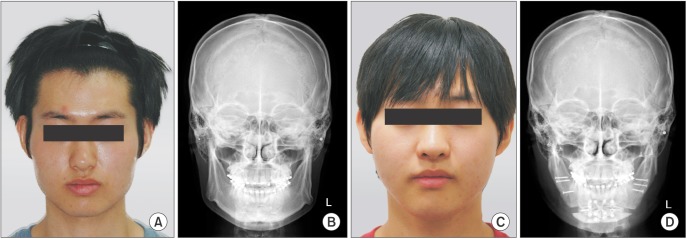

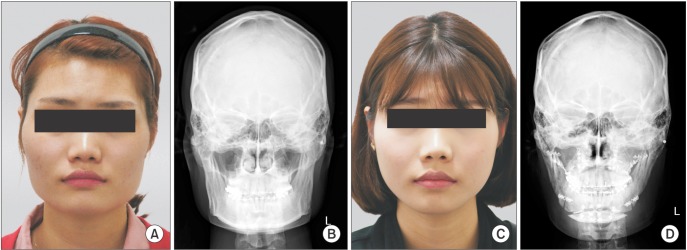

All 3 groups, i.e., Group A (mandibular angle reduction and mandibular setback osteotomy), Group B (mandibular angle resection, bilateral sagittal split ramus osteotomy and genioplasty), and Group C (mandibular angle resection, bilateral sagittal split ramus osteotomy, Le Fort I osteotomy and genioplasty), demonstrated an increase in Han's ratio. This data supported Han and Kim

9 who reported a postoperative decrease of bigonial distance by an average of 12.3 mm in 12 patients after mandibular angle ostectomy, as compared to preoperative data.

There were no significant differences in preoperative and postoperative Han's ratio for each group i.e., control, Group A, and the experimental, Group B or Group C. Thus, we assumed that using a frontal view for preoperatively planned anteroposterior movement of the maxilla and the chin played little role in postoperative esthetic improvement resulting from a reduced mandibular angle.

Han's ratio proposed in the present study can be easily calculated by placing landmarks on frontal facial images. Moreover, it can be obtained separately on the right and left to analyze the degree of correction of facial asymmetry between preoperative diagnosis and postoperative evaluation. Meanwhile, since only frontal evaluations are possible with this method, supplementary lateral assessments of angle are required.

Whitaker

17 pointed out that applying a plain and consistent method in every case is incorrect because of the ambiguity inherent in the evaluation of facial esthetics. In fact, enhancement of Han's ratio does not necessarily lead to esthetic improvement. In addition, overall facial balance and harmony with the nose, eyes and adjacent structures must be taken into consideration.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download