I. Introduction

The submasseteric space is one of three spaces that make up the main masseteric space, the other two being the temporal and the pterygomandibular spaces. It is formed by splitting the superficial layer of the deep cervical fascia that encloses the mandible and primary muscles of mastication. The contents of this space include the masseter muscle, the ramus and posterior body of the mandible, the tendinous insertion of the temporalis muscle, the medial and lateral pterygoid muscles, and the inferior alveolar nerve and vessels

1. The masseter muscle is divided into three parts: superficial, middle, and deep. All three parts originate from the zygomatic arch. Bransby-Zachary

2 found that the deep portion has a small insertion that is limited to the lateral surface of the coronoid process and upper third of the ramus of the mandible. The superficial portion has the largest insertion point that is restricted to the lower third of the ramus, specifically the posterior angle of the mandible. The middle portion was the smallest and inserted along a thin line curving posteriorly and superiorly over the middle third of the ramus

2.

Bransby-Zachary

2 demonstrated a true submasseteric space lateral to the mandibular ramus, which is a bare area between the separate attachments of the deep and middle portions of the masseteric muscle, thus resulting in a potential space. As such, the submasseteric space is located between the laterally placed, thick, quadrate master muscle and the mandibular ramus, which represents the medial border

3.

Once a submasseteric space infection is diagnosed, the key first step in resolving the infection is surgical evacuation of the pus

45. Although it is possible and occasionally more practical to drain the submasseteric space intraorally, sometimes it may be more prudent to gain access via an extraoral approach

6. As an alternative, some have suggested an extraoral incision for drainage

7.

Some surgeons have reported complications of facial nerve damage during extraoral incision and drainage (I&D) procedures and have felt that extraoral dissection is very difficult. Thus, our department has recently simplified a submasseteric space drainage technique that has resulted in successful abscess treatment. In this study, we report on this modified drainage technique and incorporate literature reviews.

Go to :

II. Technical Note

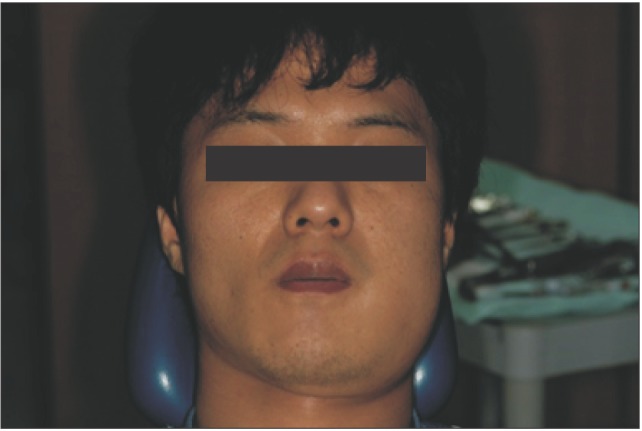

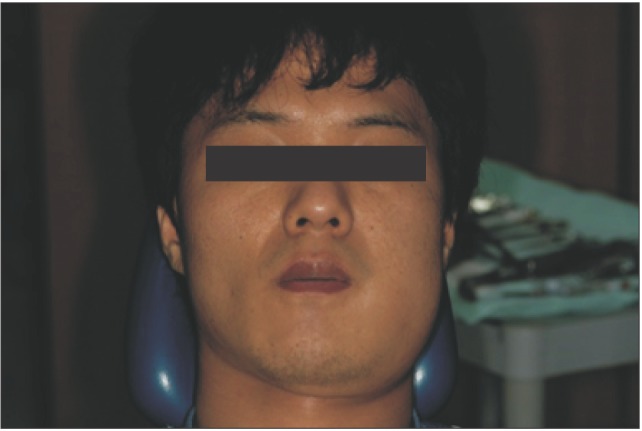

1. Case 1

A 27-year-old man visited the emergency room with trismus and painful swelling near the area of his left mandibular angle. He was only able to open his mouth 17 mm, and his body temperature was 37.2℃. His pain was so severe that the physician could not touch his swollen face. His left mandibular third molar had felt uncomfortable two days prior to presentation, but the majority of symptoms developed the morning of they presented to the emergency room. The cause of infection was thought to be pericoronitis (

Fig. 1) of the impacted third molar, as seen in the panoramic view.(

Fig. 2)

| Fig. 1The patient exhibited swelling of the mandibular angle area.

|

| Fig. 2The impacted third left, mandibular molar was thought to be the cause of infection.

|

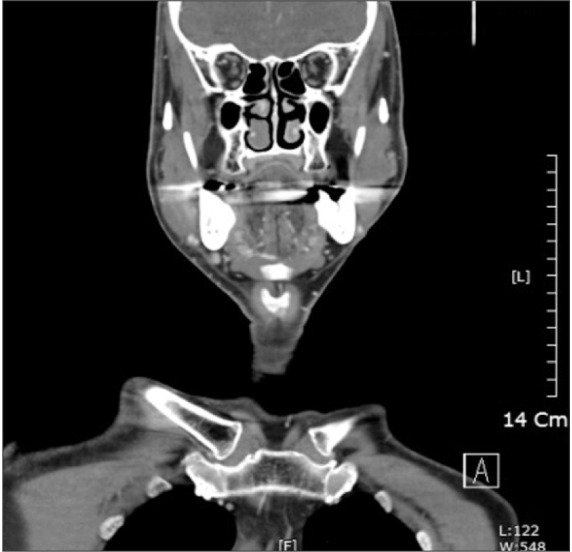

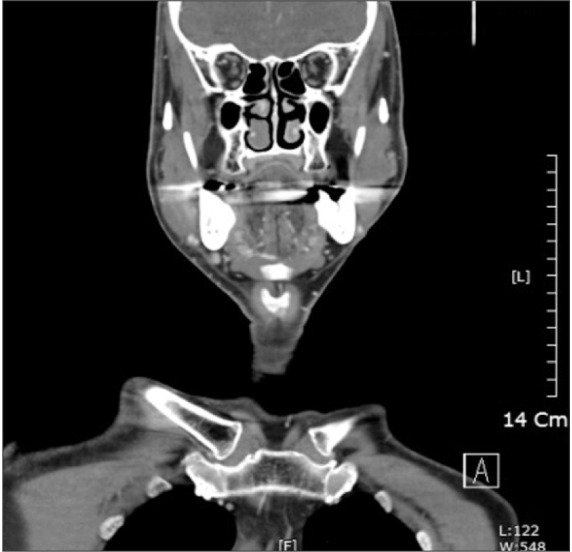

On computed tomography (CT) examination, a pus collection was found between the ramus and master muscle.(

Fig. 3)

| Fig. 3On computed tomography scan, a pus collection was found between the ramus and master muscles.

|

His complete blood count results included a total leukocyte count of 9,070 with 68.5% neutrophils and 22.2% lymphocytes, hemoglobin level of 13.2 g/L, and a platelet count of 164,000. The C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) test results were 98.23 mg/L and 9 mm/hr, respectively.

The patient was diagnosed with a submasseteric space abscess, and clamoxin and isepamicin were both administered.

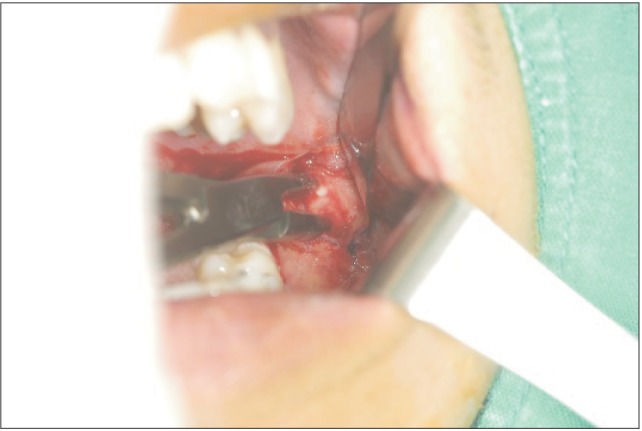

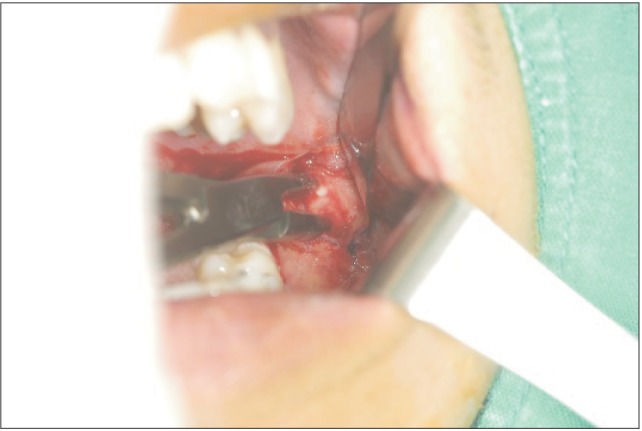

Under local anesthesia, I&D was done. After forcing the mouth open, the vestibular mucosa was incised along the anterior border of the masseter muscle. While the hemostat was in contact with the lateral surface of the ramus, an additional hemostat was introduced through the intraoral wound and directed backwards. Through the intraoral route, the masseter muscle was detached from ramus as much as possible, which was performed more easily than anticipated.(

Fig. 4)

| Fig. 4After incising the vestibular mucosa along the anterior border of the master muscle, a hemostat was introduced through the intraoral wound and directed backwards. While the instrument was in contact with the lateral surface of the ramus, the masseter muscle was detached from the ramus as much as possible.

|

After detaching the masseter muscle from the ramus, a 1.0 cm horizontal incision was marked 2.0 cm below the lower border of the mandibular angle. The tip of hemostat was pushed toward the incision marking, lifting it up and allowing for incision of the elevated skin only. The tip of hemostat penetrated out through the incised skin.(

Fig. 5)

| Fig. 5After detachment of the masseter muscle from the ramus, a 1.0 cm horizontal incision was marked 2.0 cm below the lower border of the mandibular angle. The tip of the hemostat was pushed toward the incision, lifting up on the incision marking. After incising only the elevated skin, the tip of the hemostat was pushed through the incised skin.

|

The drain was then attached to the hemostat and the hemostat was withdrawn. After checking the position of the drain intraorally, the intraoral incision was closed with absorbable suture and the end of the drain was sutured to the skin with 6-0 nylon.(

Fig. 6) The pus was sent for antibiotic sensitivity testing and culture.

| Fig. 6The drain was attached to the hemostat, and the hemostat was withdrawn. After checking the position of the drain intraorally, the intraoral incised wound was closed with an absorbable suture.

|

Streptococcus salivarius was identified as the causative organism. The drain was removed after being in place for ten days. The extraoral wound was left to heal on its own. The patient was discharged after 14 days without complications.

2. Case 2

A 46-year-old man had symptoms of facial swelling and mild pain anterior to the left parotid gland for a total of five days. Although he had no fever, he appeared mildly ill on examination. The patient was found to have a firm, tender mass in the left cheek located anterior to the parotid gland and just superior to the mandible. On panoramic view, the retained root of the second molar was thought to be the cause. He had a mild trismus with the ability to open his mouth 20 mm. His complete blood count results included a total leukocyte count of 12,500 with 70.3% neutrophils and 17.8% lymphocytes, a hemoglobin level of 12.6 g/L, and a platelet count of 410,000. C-reactive protein and ESR test results were 103.45 mg/L and 68 mm/hr, respectively. His blood glucose was 227 mg/dL.

A CT scan revealed a thickening of the left masseter muscle, which was suggestive of cellulitis with abscess formation within the masseter muscle. Typically, submasseteric space abscesses will be found between the ramus and the master muscle, but in this patient, the abscess cavity was seen within the masseter muscle itself.(

Fig. 7)

| Fig. 7Cellulitis with abscess formation within the masseter muscle was seen on computed tomography scan.

|

The patient was diagnosed a submasseteric space abscess according Kay and Killey's report

5. Combicin, trizel and isepamicin antibiotics, along with amaryl, an antihyperglycemic drug, were administered. The patient was sent to the operating room for drainage. The same I&D procedure, as described in Case 1, were performed under general anesthesia.

The drain was removed after five days, and Staphylococcus epidermidis was identified as the causative organism. The extraoral wound was left to heal on its own.

3. Case 3

A 32-year-old man visited the emergency room with trismus and painful swelling of the masseter muscle. He was afebrile with a maximum mouth opening was 20 mm. The source of masseteric space infection was thought to be from the left mandibular third molar. Seven days prior to presentation, local clinics tried to drain the pus intraorally, but the condition did not improve.

His complete blood count results included a total leukocyte count of 7,130 with 57.33% neutrophils and 35.28% lymphocytes, a hemoglobin level of 12.9 g/L, and a platelet count of 249,000. C-reactive protein and ESR test results were 52.26 mg/L and 16 mm/hr, respectively.

Panoramic imaging revealed the causative third molar on the left side. CT imaging was consistent with a submasseteric space abscess.(

Fig. 8)

| Fig. 8A hypodense area with an enhanced peripheral rim was seen between the ramus and the overlying master muscle. The hypodense area indicates a pus collection.

|

The patient was diagnosed a submasseteric space abscess. Cefazoline and isepamicin were administered empirically. The same drainage procedures, as described above, were performed under general anesthesia.

The causative third molar was extracted during the drainage procedure and the intraoral incision wound was closed immediately. The patient was discharged after seven days without complications. The drain was removed after ten days and the extraoral wound was observed to heal well.

4. Case 4

A 65-year-old man visited the emergency room with trismus and painful swelling at the right mandibular angle. He had been unable to sleep due to severe pain for several days. He had a mild fever of 38.5℃ and his maximal mouth opening was 17 mm. His symptoms developed seven days prior to presentation, at which time, he had his right mandibular first molar extracted due to chronic periodontitis. On radiography, an abscess was observed between the ramus and masseter muscles, and an extraction socket was observed on the right mandibular first molar.(

Fig. 9)

| Fig. 9Abscess cavity between the ramus and masseter muscles and an extracted socket on the first right mandibular molar.

|

His complete blood count results included a total leukocyte count of 7,510 with 67.3% neutrophils and 22.4% lymphocytes, a hemoglobin level of 13.4 g/L, and a platelet count of 227,000. C-reactive protein and ESR test results were 49.54 mg/L and 13 mm/hr, respectively. His blood glucose level was 241 mg/dL with an HbA1c of 9.9%.

The patient was diagnosed with a submasseteric space abscess. Combicin was administyterd for the first seven days and combicin was discontinued. Instead, clamoxin and gentamycin were administerd for the following week. The antihyperglycemic drug, amaryl, was administered as well. The same drainage procedures, as described above, were performed under general anesthesia. The patient was discharged after 14 days without complications. The drain was removed on the day of discharge and the extraoral wound healed well.

Go to :

IV. Discussion

Infection of the submasseteric space most frequently originates from mandibular molar teeth. Pericoronitis of the gingival flap of third molars or caries-induced dental abscesses can be found in most masseteric space infections

6.

Symptoms of a submasseteric space infection vary from moderate to severe and are dependent on a variety of factors relating to the organisms involved, host defenses, and the therapy being used. Swelling and tension caused by gross collections of pus in a confined space lead to varying degrees of pain. Involvement of the bordering masseter initiates trismus, which is a consistent diagnostic feature. Trismus is an early conclusive feature and mouth opening may be restricted to less than one centimeter. The marked degree of limitation in jaw movement often seems excessive and inconsistent with the amount of swelling present

35. Unilateral cervical adenitis is typically present. This systemic reaction is considerable with high fever, malaise, and toxicity

5. Including abscess formation, suppuration within the masseter muscle can also be considered to be a submasseteric space abscess

5. In Case 2, there was no abscess formation between the masseter muscle and ramus, but myositis and masseter muscle suppuration implicated a submasseteric space abscess.

Once a submasseteric space infection is diagnosed, the key to resolving the infection is surgical evacuation of the pus

45. Partial treatment with antibiotics without surgical drainage may contribute to a chronic abscess that does not resolve. Such partial treatment may account for the typical absence of systemic signs and symptoms at the time of clinical presentation. Instead, there is usually firm, relatively painless, non-fluctuant facial swelling with progressive trismus that may mimic parotitis or a tumor

8.

Submasseteric abscesses are commonly misdiagnosed as acute or chronic parotitis; this is because the submasseteric space is in close proximity to the parotid gland, with only fibromuscular fascia in between. This is especially true when the usual dental source of the infection is not present. A thorough medical history and clinical examination as well as CT are important tools in the differential diagnosis

4. Patients with parotitis usually have a history of recurrent parotid swelling, exacerbated by increased salivary flow

9. Trismus is mild with parotitis, whereas marked trismus is a prominent hallmark with a submasseteric space abscess

9. Alternative lesions that may cause facial swelling include benign masseteric hypertrophy, venous intramuscular angioma, buccal lymphangioma, superficial parotid tumor, or chronic osteomyeilits

10.

The literature primarily describes an extraoral approach to drainage

7. In 1963, Kay and Killey

5 described drainage techniques. These techniques were intraoral and through- and-through approaches. Preferably under endotracheal anesthesia, the recommended standard intraoral incision extends down the anterior border of the ramus from the coronoid process and deviates below into the sulcus along the line of the external oblique ridge to end at the first molar. A pair of closed sinus forceps or a hemostat is introduced through the wound and directed backwards, such that the instrument is in contact with the lateral surface of the ramus. When extraoral drainage is considered, a radical through-and-through technique using an external incision below and behind the angle for passage of the drain is used

5.

The intraoral approach is often impractical due to presence of trismus and the inability to establish dependent drainage

11. In such patients, the intraoral approach could compromise the airway postoperatively because of persistent bloody or purulent oozing. Intraoral drains may be difficult to maintain and can be aspirated if inadvertently loosened

12. According to Haggerty and Laughlin

11, an approach to the submasseteric space via incision along the external oblique ridge (buccal vestibule) or lateral and parallel to the pterygomandibular raphe is technically feasible, but is more difficult in an infected patient who has trismus. Sharp dissection is carried through the buccinator muscle and blunt dissection is continued through the masseteric spaces

11. Incising the buccal vestibule along the external oblique ridge or parallel to the paterygomandibular raphe requires a small mouth opening. Except in cases of complete trismus, incision and dissection may be possible.

The submasseteric space may be entered by dissecting at the external mandibular angle of the mandible. This approach avoids the mandibular branch of the facial nerve

6. An extraoral approach allows for dependent drainage of the masticatory space at the insertion of the muscle sling on the inferior border at the mandibular angle

6. The abscess is drained via a horizontal incision 2.0 to 2.5 cm below the lower border of the mandible. A subplatysmal flap is raised and the masseter muscle is breached to expose the abscess through the pterygomasseteric sling

13.

Drainage will be performed under local or general anesthesia. Adequate local anesthesia is usually administered at the mandibular angle and along the mandibular ramus; however, this may cause intolerable pain to some patients. Thus, general anesthesia is commonly used as long as the patient's condition permits. Trismus may hinder intubation, though a skilled anesthesiologist can circumvent this problem.

The modified drainage technique in this study has several advantages. First, damage to the marginal branch of the facial nerve is greatly minimized. Sometimes, an unskilled surgeon may cause facial nerve damage during the extraoral I&D. This modification does not require dissection of subcutaneous tissue, fascia, or the pterygomasseteric sling, and as such, the marginal branch of the facial nerve may be protected. Second, this technique is very simple. Many oral surgeons and dentists are accustomed to intraoral approaches in comparison to cervical approaches. Third, this procedure can be done with trismus. This modified technique was possible under local anesthesia with only a 15 mm mouth opening. When severe trismus exists, intubation is very difficult and special equipment such as a bronchoscope managed by a skilled anesthesiologist may be required.

Meanwhile, our technique also has limitations. First, multiple infections involving nearby spaces, such as the parapharyngeal space, submandibular space, pterygomadibular, and temporal spaces, may require a more extensive I&D procedure than this simple modification. Second, in contrast to the intraoral I&D technique, the extraoral technique leaves a visible external scar. However, if surgeons want dependent drainage, the extraoral route may be chosen. Third, if intraoral suturing is loosened and there is bloody or purulent oozing, the patient may be bothered.

There are several factors to consider when using this modified drainage technique. First, when local anesthesia is used, pain may hinder intraoral procedures, and as such, ample local anesthetic injection is necessary for satisfactory drainage pain prevention. Infiltration along the mandibular angle area and underlying ramal area are both intraorally and extraorally very important for reducing pain. Sometimes, general anesthesia is chosen because after using muscle relaxants, the mouth opening usually increases, permitting a more comfortable approach. Thus, the surgeon must use caution in selecting the method of anesthesia. Additionally, when a patient with a submasseteric space abscess has minimal symptoms, intraoral I&D can adequately treat the problem, so random use of this modified technique should be avoided.

In conclusion, extraoral I&D techniques require dissection and are sometimes difficult for unskilled surgeons. They also pose inherent potential damage to the facial nerve. This modification method starts with intraoral dissection, followed by puncturing of the skin under the mandibular angle. The technique does not require dissection, as the surgeon can check the position of the drain through the intraoral incision site. Even if the patient has trismus, incision and dissection of the masseter muscle from mandibular ramus are feasible. When a masseteric space infection is diagnosed, multiple space involvement is ruled out, and dependent drainage is required, this modified drainage technique can be useful.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download