Abstract

Intramuscular hemangioma (IMH) is a rare vascular disease involving skeletal muscle, comprising only 0.8% of hemangiomas. About 10% to 15% of IMHs occur in the head and neck region, mostly involving the masseter muscle. IMH occurs mostly in childhood, but is often not found until unexpected enlargement, pain, or cosmetic asymmetry occurs in adulthood. Several non-surgical treatments including cryotherapy, sclerosant injection, and arterial ligature have been described, but complete surgical resection is the curative intervention. In this report, we present two rare cases of IMH. One IMH case in a 48-year-old male occurred in the masseter muscle feeding from the transverse facial artery. Embolization of the distal branch of the facial artery was first conducted, and then the buccal mass was removed surgically via the intraoral approach. A second IMH case in a 58-year-old female occurred in the orbicularis oris muscle feeding from the superior labial artery, and the mass was excised surgically without embolization.

Intramuscular hemangioma (IMH) is a rare vascular disease involving skeletal muscle, comprising only 0.8% of all hemangiomas1. About 10% to 15% of IMHs occur in the head and neck region, mostly involving the masseter muscle23. IMH of the head and neck may be localized mainly in the masseter muscle (36%), trapezius (24%), periorbital muscles (12%), sternocleidomastoid muscle (10%), temporalis muscle, or orbicularis oris muscle4. IMH in the orbicularis oris muscle is very rare56.

IMH occurs mostly in childhood. However, it often is not found until unexpected enlargement, pain, or cosmetic asymmetry occurs in adulthood. Several non-surgical treatments including cryotherapy, sclerosant injection, and arterial ligature have been described, but complete surgical resection is the curative intervention78. In the case of a large feeding vessel, embolization of the feeding vessels is recommended to reduce the risk of perioperative and postoperative bleeding9.

We present two rare cases of IMH—one IMH case in the masseter muscle feeding from the transverse facial artery (TFA) and a second IMH case in the orbicularis oris muscle feeding from the superior labial artery.

Written informed consent was obtained from the patients for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

In August 2014, a 48-year-old male visited our clinic with the chief complaint of swelling of the left buccal area.(Fig. 1) On palpation, a painless and compressible mass was found near the left masseter muscle. There was no wattle sign or beating, and only bloody discharge was observed in fine needle aspiration. Immediately following fine needle aspiration, the patient reported increased swelling of the left cheek. Initial diagnosis was a vascular lesion, such as hemangioma or vascular malformation.

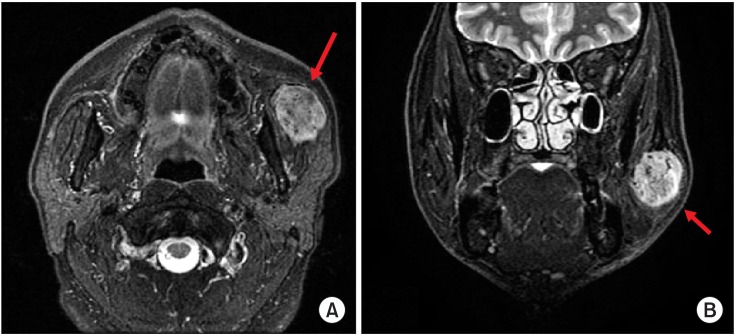

On magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), a mass about 2.2×3.3×3.4 cm at the left masseter muscle was strongly enhanced with heterogeneous T2 hyperintensity.(Fig. 2) There were multiple intratumoral and peritumoral vascularities visualized as signal voids. This mass was suggestive of IMH of the left masseter muscle.

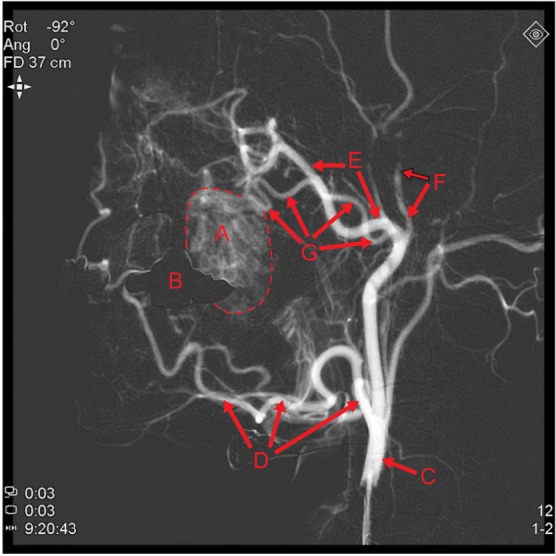

External carotid angiography (ECA) was performed for further evaluation. A vascular mass feeding from the left TFA and the maxillary artery was identified.(Fig. 3, 4) In the lateral view of angiography, the prosthesis of a dental implant on the upper left first molar overlapped the mass. The mass became blushed and then disappeared over time as contrast agent diffused through the blood vessels.

Based on clinical and radiographic examinations, the patient was provisionally diagnosed with IMH of the left masseter muscle feeding from the left TFA (main) and maxillary artery. To reduce the risk of perioperative and postoperative bleeding, embolization of the distal TFA branch was performed.(Fig. 5) A guiding catheter (diameter of 5 Fr, Enboy; DePuy Synthes, West Chester, PA, USA) was inserted in the left ECA, then selection of the distal branch of the TFA was performed by Prowler select plus (Cordis, Miami, FL, USA). (Fig. 5. A) An embolizing agent, polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) particle (contour of 150-200 nm), was injected at slow speed into the selected site. PVA particles are invisible in angiography, so the contrast agent was injected locally to the selected site to verify embolization. Because the pathway was blocked at the selected site, back pressure was observed intensively at the backside of the selected site instead of the mass.(Fig. 5. B) To confirm effective embolization, contrast agent was injected into the ECA again. The mass was faintly visualized although sufficient time had passed.(Fig. 5. C) That represents successful blocking of blood supply to the mass. Blood supply from the maxillary artery was not significant, so embolization of the vessel was not performed.

The following day, there was no change in the strongly enhancing mass at the left masseter muscle on post-embolization MRI.(Fig. 6) The swelling of the patient's left cheek also remained unchanged. Two days after embolization, the buccal mass was excised via intraoral approach under general anesthesia. After insertion of a fine tube to Stensen's duct for position marking, mucosal incision anterior to Stensen's duct was performed. Local control of bleeding and direct resection of the mass were achieved.(Fig. 7) Based on biopsy result, IMH was confirmed.(Fig. 8) After the operation, swelling and patient discomfort resolved without any significant complications. At the eight month check up, the patient reported no symptoms and was thereafter lost to follow-up.

In April 2015, a 58-year-old female visited our clinic. The patient's upper lip was swollen in the right angular region. (Fig. 9) In another dental clinic, she had undergone laser therapy at that area more than 10 years prior for the same symptom, but the mass had progressively enlarged. There was neither wattle sign nor beating.

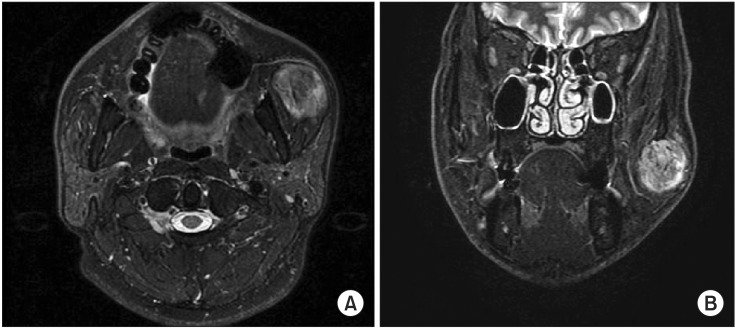

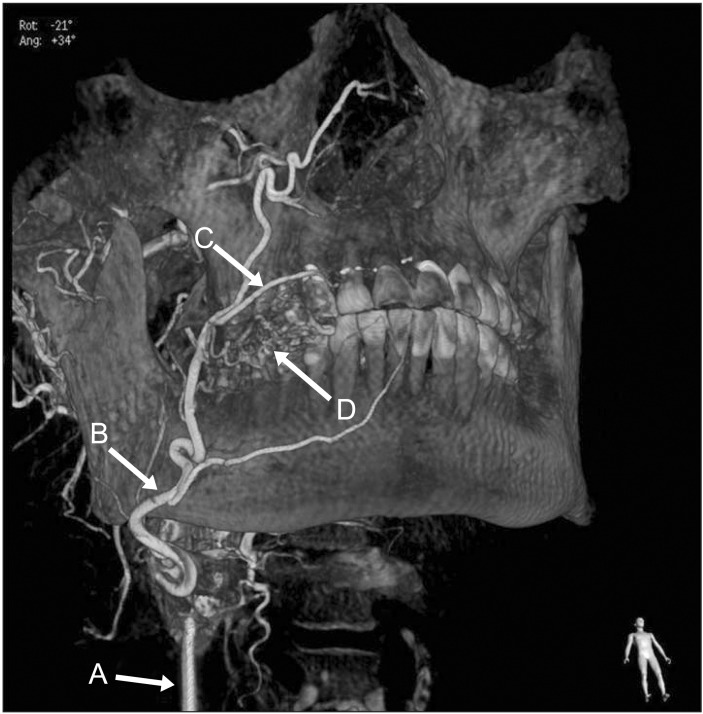

A 2.7 cm ovoid submucosal mass was well defined on MRI STIR (short-T1 inversion recovery) and T2 images (Fig. 10), and the mass was feeding from small branches of the superior labial artery on angiography.(Fig. 11) The mass was excised under general anesthesia without embolization. Via the intraoral approach, mucosal incision on the buccal mucosa and undermining of the mass were conducted under local bleeding control. IMH was confirmed on biopsy.(Fig. 12, 13)

The term “hemangioma” has been applied to a wide variety of vascular lesions and continues to be used to describe vascular malformations. Several authors have recently suggested that vascular malformations should be distinguished from hemangiomas10111213. In 1982, Mulliken and Glowacki proposed a simple classification system of vascular anomalies—hemangiomas versus vascular malformations. In 1992, the International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies adopted Mulliken and Glowacki's classification system and modified the classification of vascular malformations versus vascular tumors10.

Vascular malformations are present at birth and enlarge in proportion to the growth of the child11. They are subcategorized as slow-flow vascular malformations (capillary malformation, venous malformation, and lymphatic malformation), fast-flow vascular malformations (including arteriovenous malformation), and complex-combined vascular malformations. They radiographically show cystic or dysplastic vessels, usually involving multiple tissue planes12. Phlebolith (especially in venous malformation on computed tomography [CT]) and signal void (especially in arteriovenous malformation on MRI) are common features. Histologically, vascular malformations have quiescent endothelium. They do not involute and persist throughout life1014. There is often a wattle sign, beating, and thrilling in vascular malformations.

On the other hand, vascular tumors are true neoplasms with cellular hyperplasia and include infantile hemangioma, congenital hemangioma, and hemangioendothelioma. On radiographic images, they show a well-defined mass in the majority of patients13. Arteriovenous shunting and phlebolith are unusual in vascular tumors. Histologically, they grow by endothelial proliferation, and tumors can grow, regress, or persist. Adipose tissue can be observed, because regressed tumors are replaced by adipose tissue1014. Wattle sign, beating, and thrilling are uncommon in vascular tumor.

IMH is a special form of hemangioma involving skeletal muscle and comprises only 0.8% of all hemangiomas1. About 10% to 15% of IMHs occur in the head and neck region, mostly involving the masseter muscle23. IMH has developed vessels embedded within muscle tissue usually in the deep layer. They therefore have somewhat different characters from other types of hemangiomas.

Due to the rarity of these tumors and their deep location and unfamiliar presentation, inaccurate diagnosis, inappropriate excision, and unnecessary risk to the facial nerve occur when IMH is present in the face4. Over 90% of all IMHs are misdiagnosed15. Differential diagnosis of IMH includes lymphangioma, lymphomas, rhabdomyosarcoma, and schwannomas9. In particular, IMH arising from the masseter muscle is frequently confused with parotid tumor715.

IMH occurs mostly in childhood. However, it is often not found until unexpected enlargement, pain, or cosmetic asymmetry occurs in adulthood. Trigger factors include hormonal change, infection, or trauma.

In 1972, Allen and Enzinger16 retrospectively reviewed the histopathological findings of a large group of patients described as having IMH. They classified these patients into three categories based on vessel size and histological features: small-vessel type (capillary type, less than 140 µm), large-vessel type (cavernous type, more than 140 µm), and mixed-vessel type. However, Yilmaz et al.13 argued that the description of the small-vessel type was identical to that of intramuscular capillary-type hemangioma, while the description of large-vessel type was more consistent with what is now designated as venous malformation. Capillary-type IMH accounts for 50% of all IMH, and 68% of these tumors are in the head and neck4.

To diagnosis IMH, ultrasound and CT are used along with clinical examination. MRI is considered the gold standard 10111215 and typically shows a well-marginated soft tissue mass. On T2 and STIR images, lesions appear homogeneous and moderately hyperintense during the proliferative phase and increased heterogeneity during the involution phase owing to areas of fat replacement. Flow voids may be seen at the periphery of the lesion on spin-echo sequences, reflecting high-flow arterial feeders10.

Angiography is useful for diagnosis of arteriovenous malformation and is not routinely performed for diagnosis of hemangioma. However, angiography may be helpful when the feeding artery is large. Fine needle aspiration is not recommended due to the risk of hemorrhage9.

Non-surgical treatments such as cryotherapy, sclerosant injection, embolization, and arterial ligature have been described, but there is dispute about the results of these treatments. Therefore, non-surgical treatments are currently recommended only when surgery is contraindicated or refused7. Complete surgical resection is the curative intervention. For intramasseteric cases, the intraoral approach for surgical resection may be useful as it avoids any visible scar or facial nerve dissection78.

Localized recurrence rate ranges from 9% to 28%, despite wide resection of the tumor due to the absence of capsule surrounding the tumor2. Minor feeding vessels and residual tumor may be responsible for the recurrence rate16.

In case 1, there was no wattle sign or beating palpation. Phlebolith was not found. A mass with well-defined border, strongly enhanced with heterogeneous T2 hyperintensity was found on MRI.(Fig. 2) On angiography, a vascular mass feeding from the left TFA (main) and the maxillary artery was found.(Fig. 3) TFA is a branch arising from the superficial temporal artery, and it anastomoses with the facial artery, mesenteric artery, infraorbital artery, and others17. No remarkable changes were found by preoperative embolization of TFA (Fig. 5), and the mass was surgical excised by intraoral approach two days later.(Fig. 7) In case 2, there was a similar radiographic exam (Fig. 10, 11), and there was wattle sign or beating.

On microscopic exam of case 1, well developed vessels with proliferation of endothelial cells between skeletal muscle tissue were found.(Fig. 8. A) Capillaries were predominant, and large vessels were seen occasionally.(Fig. 8. B) A large amount of adipose tissue was observed because regressed tumors are replaced by adipose tissue.(Fig. 8. C) Larger vessels (possibly from feeding vessels) were also observed within the mass, but there was no obvious arteriovenous shunting.(Fig. 8. D) This tumor was therefore considered mixed-type IMH.

In case 2, large vessels (possibly from feeding vessels) were observed in the lateral side of the mass (Fig. 12. A), and developed vessels between skeletal muscle tissues were found.(Fig. 12. B) However, there was only a small amount of adipose tissue in this case. Immunohistochemically, endothelial cells were positive for CD34 (Fig. 13), an antigen protein that shows expression on immature hematopoietic cells and endothelial cells. This case was therefore considered IMH.

In conclusion, IMHs can be diagnosed using MRI, angiography, and excisional biopsy. Preoperative embolization and surgical excision are recommended. In these two rare cases of IMH in masseter and orbicularis oris muscle, the intraoral approach provided a direct approach and allowed removal of the tumor without any visible scar or facial nerve dissection.

Acknowledgements

Authors' contributions: IKK carried out the operation and related treatment, contribution of conception of the report, HYC and JHS carried out the operation and critical revising. JHS, DHL, and JMJ participated in the treatment, collection of data and drafting the manuscript. JMK, ISP carried out histological examination and contribution of the histological opinion. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

1. Watson WL, McCarthy WD. Blood and lymph vessel tumors. Srug Gynecol Obstet. 1940; 71:569–588.

2. Wolf GT, Daniel F, Krause CJ, Kaufman RS. Intramuscular hemangioma of the head and neck. Laryngoscope. 1985; 95:210–213. PMID: 3968956.

3. Gordon JS, Mandel L. Masseteric intramuscular hemangioma: case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014; 72:2192–2196. PMID: 24976110.

4. Odabasi AO, Metin KK, Mutlu C, Başak S, Erpek G. Intramuscular hemangioma of the masseter muscle. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1999; 256:366–369. PMID: 10473832.

5. Chan MJ, McLean NR, Soames JV. Intramuscular haemangioma of the orbicularis oris muscle. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1992; 30:192–194. PMID: 1622968.

6. Kinni ME, Webb RI, Christensen RE. Intramuscular hemangioma of the orbicularis oris muscle: report of case. J Oral Surg. 1981; 39:780–782. PMID: 6944460.

7. Righini CA, Berta E, Atallah I. Intramuscular cavernous hemangioma arising from the masseter muscle. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2014; 131:57–59. PMID: 23845293.

8. Ichimura K, Nibu K, Tanaka T. Essentials of surgical treatment for intramasseteric hemangioma. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1995; 252:125–129. PMID: 7662343.

9. Righi S, Boffano P, Malvè L, Rossi P, Zanardi F, Pateras D. Intramural perimasseteric hemangiomas of the inner cheek. J Craniofac Surg. 2015; 26:959–960. PMID: 25974807.

10. Chaudry MI, Manzoor MU, Turner RD, Turk AS. Diagnostic imaging of vascular anomalies. Facial Plast Surg. 2012; 28:563–574. PMID: 23188683.

11. Donnelly LF, Adams DM, Bisset GS 3rd. Vascular malformations and hemangiomas: a practical approach in a multidisciplinary clinic. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000; 174:597–608. PMID: 10701595.

12. Flors L, Leiva-Salinas C, Maged IM, Norton PT, Matsumoto AH, Angle JF, et al. MR imaging of soft-tissue vascular malformations: diagnosis, classification, and therapy follow-up. Radiographics. 2011; 31:1321–1340. PMID: 21918047.

13. Yilmaz S, Kozakewich HP, Alomari AI, Fishman SJ, Mulliken JB, Chaudry G. Intramuscular capillary-type hemangioma: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Pediatr Radiol. 2014; 44:558–565. PMID: 24487677.

14. Rosbe KW, Hess CP, Dowd CF, Frieden IJ. Masseteric venous malformations: diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010; 143:779–783. PMID: 21109077.

15. Lee SK, Kwon SY. Intramuscular cavernous hemangioma arising from masseter muscle: a diagnostic dilemma (2006: 12b). Eur Radiol. 2007; 17:854–857. PMID: 17225132.

16. Allen PW, Enzinger FM. Hemangioma of skeletal muscle. An analysis of 89 cases. Cancer. 1972; 29:8–22. PMID: 5061701.

17. Yang HJ, Gil YC, Lee HY. Topographical anatomy of the transverse facial artery. Clin Anat. 2010; 23:168–178. PMID: 19918875.

Fig. 1

Case 1. Preoperative clinical view. Swelling of the patient's left cheek is shown (arrow). A. Facial view. B. Lateral view.

Fig. 2

Case 1. Preoperative magnetic resonance imaging. A well-marginated mass (arrows) was found in the left masseter muscle. A. Axial view. B. Coronal view.

Fig. 3

Case 1. Preoperative external carotid angiography, lateral view. The main mass (‘A’) is shown near the overlapped image of a dental prosthesis (‘B’). It is feeding from the transverse facial artery (‘G’) and maxillary artery (‘E’). (‘A’: main mass, ‘B’: overlapped image of dental prosthesis [maxillary left implant and maxillary right 3-unit bridge], ‘C’: external carotid artery, ‘D’: facial artery, ‘E’: maxillary artery, ‘F’: superficial temporal artery, ‘G’: transverse facial artery [main])

Fig. 4

Case 1. Preoperative external carotid angiography, lateral view. The mass (‘A’) became blushed by contrast agent injection (A-C), then gradually disappeared with time (D). (‘A’: main mass, ‘B’: overlapped image of dental prosthesis [maxillary left implant and maxillary right 3-unit bridge])

Fig. 5

Case 1. Procedure of embolization. (A) Selection of the distal branch of the transverse facial artery was achieved by Prowler select plus. (B) After embolization by polyvinyl alcohol particle injection (no picture), the contrast agent was injected locally to the selected site, and back pressure was observed intensively at the backside of the selected site. (C) Contrast agent was injected into the external carotid angiography again, and the mass was faintly visualized although sufficient time had passed. (‘A’: main mass, ‘B’: overlapped image of dental prosthesis [maxillary left implant and maxillary right 3-unit bridge])

Fig. 6

Case 1. Post-embolization magnetic resonance imaging. No significant changes appeared. A. Axial view. B. Coronal view.

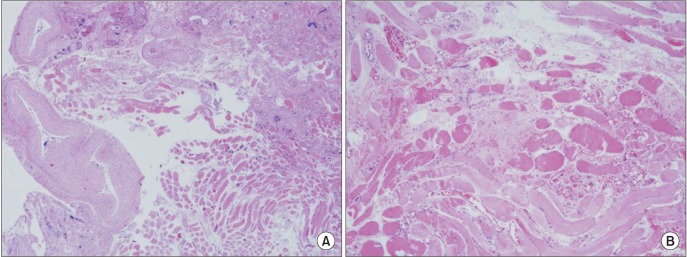

Fig. 8

Case 1. Microscopic view of the mass. A. Developed vessels with proliferation of endothelial cells between skeletal muscle tissue can be identified (H&E staining, ×100). B. Capillaries are predominant, and large vessels are seen occasionally (H&E staining, ×200). Many adipose tissues can be observed (C: H&E staining, ×40), and large vessels (possibly from feeding vessels) are also observed within the mass (D: H&E staining, ×40).

Fig. 9

Case 2. Preoperative clinical view of the patient. The patient's upper lip is shown with swelling in the right angular region.

Fig. 10

Case 2. Preoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). A well-marginated mass was found in the right upper lip on MRI STIR (short-T1 inversion recovery) axial images (A) and T2 coronal images (B).

Fig. 11

Case 2. Preoperative angiography of the patient. The mass was feeding from small branches of the superior labial artery. (‘A’: external carotid artery, ‘B’: facial artery, ‘C’: superior labial artery, ‘D’: main mass)

Fig. 12

Case 2. Microscopic view of the mass of the patient. Large vessels (may be from feeding vessels) are observed in the lateral side of the mass (A: H&E staining, ×40), and developed vessels with proliferation of endothelial cells between skeletal muscle tissues can be identified (B: H&E staining, ×100).

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download