Abstract

Neurilemmomas are well-encapsulated, benign, slow-growing tumors originating from Schwann cells of the nerve sheath surrounding cranial, peripheral, or autonomic nerves. Intraoral neurilemmomas are relatively rare and have a wide variety of morphologic and radiologic features. This makes differential diagnosis difficult, and only histopathological features can lead to a definitive neurilemmoma diagnosis. In this report, we present the case of a 30-year-old woman whose chief complaint was a solitary, nodular mass on the right floor of the mouth. After computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging, we performed an incisional biopsy that showed the typical characteristics of a neurilemmoma. The mass was removed completely through an intraoral surgical approach. Despite losing a portion of the lingual nerve, the patient did not complain of any specific discomfort. Wound healing was uneventful and there were no signs or symptoms of recurrence.

Neurilemmomas are benign, encapsulated tumors originating from Schwann cells of the nerve sheath1. Intraoral neurilemmomas are rare, and it is difficult for clinicians to distinguish neurilemmomas from other benign or malignant tumors2. When neurilemmomas occur in the sublingual area, it is important to rule out sublingual gland tumors. A definitive diagnosis of neurilemmoma can only be made by biopsy. Here, we report a case of a 30-year-old woman presenting with solitary swelling in the sublingual area, later confirmed as a neurilemmoma by incisional biopsy.

A 30-year-old female presented with swelling of the right floor of the mouth that had persisted for approximately two weeks. The patient did not know exactly when the swelling had started, but reported that the swelling had progressively increased in size. Upon examination the mass was about 4.5 cm in size. The only symptom reported was a distortion of the tongue's position to the contralateral side. The patient's medical and dental histories were unremarkable.

The intraoral lesion was a well-demarcated, elliptical nodular mass covered by normal oral mucosa in the right floor of the mouth. The mass measured 40×20 mm in diameter.(Fig. 1) No symptoms suggesting paresthesia of the lingual or hypoglossal nerve were detected. The mass was slightly movable and was not observable upon extraoral examination.

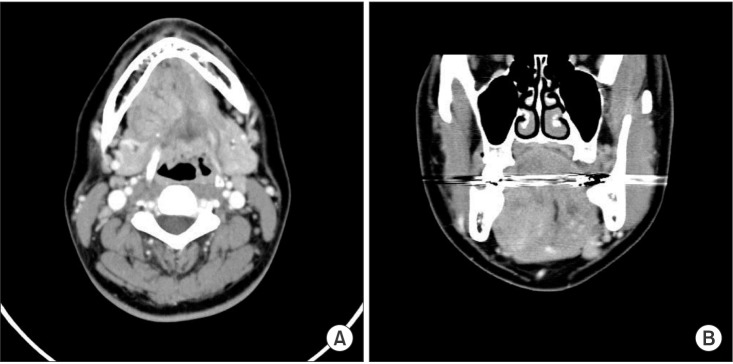

Computed tomography (CT) images showed a heterogeneously enhancing lesion filling the right posterior sublingual and submandibular space. There was delayed enhancement and local fluid accumulation was detected in the lesion. The mass was seen pushing the right genioglossus muscle contralaterally, the right mylohyoid muscle, hyoglossus muscle, and the anterior belly of digastric muscle inferiorly, and the submandibular gland posteriorly. No significant lymph nodes were found. Malignancy or vascular malformation was suspected.(Fig. 2) Magnetic resonance (MR) images were evaluated to determine the boundaries and internal characteristics of the lesion.

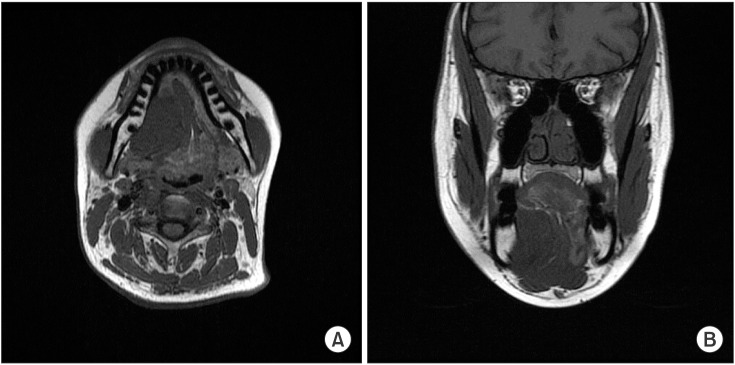

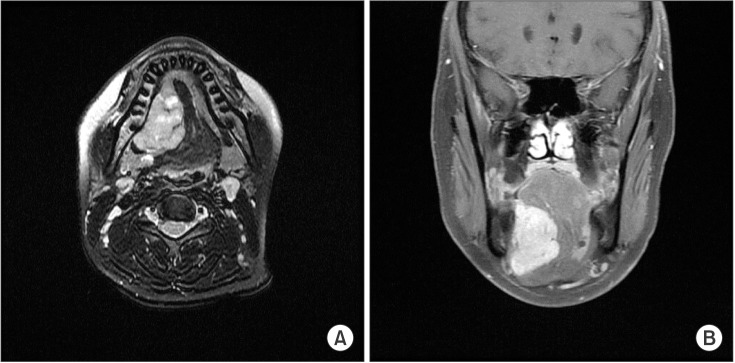

MR images showed a heterogeneously enhancing lesion occupying the right sublingual space and pushing the mylohyoid muscle inferiorly and the extrinsic muscles of the tongue internally. The absence of invasion of the surrounding muscles was characteristic of a benign tumor, but we could not rule out malignancy originating from the sublingual gland based on the images.(Fig. 3, 4)

The clinical diagnosis was a sublingual gland tumor, not ruling out malignancy. The possibility of a neurogenic tumor was also considered. Incisional biopsy with frozen section biopsy was performed under general anesthesia.(Fig. 5) A biopsy confirmed neurilemmoma without suspicion of malignant transformation.

Complete surgical excision was conducted under general anesthesia about 3 weeks after the biopsy. An intraoral approach was used to avoid external scarring. The main mass was infiltrated by a branch of the lingual nerve, and a portion of the nerve had to be sacrificed for complete removal of the mass. The patient was discharged after an uneventful healing process. No signs or symptoms of recurrence were detected 1 month after the operation. We plan to perform follow-up enhanced paranasal sinus CT in the 6th month after the operation.

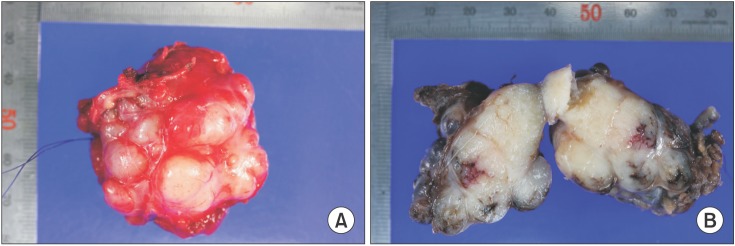

The grayish-yellow mass was well-encapsulated and ovoid in shape, measuring about 50×40×30 mm in size.(Fig. 6. A) Upon dissection, nodularity was detected. More than ten pieces of exophytic lobules were detected by gross examination.(Fig. 6. B)

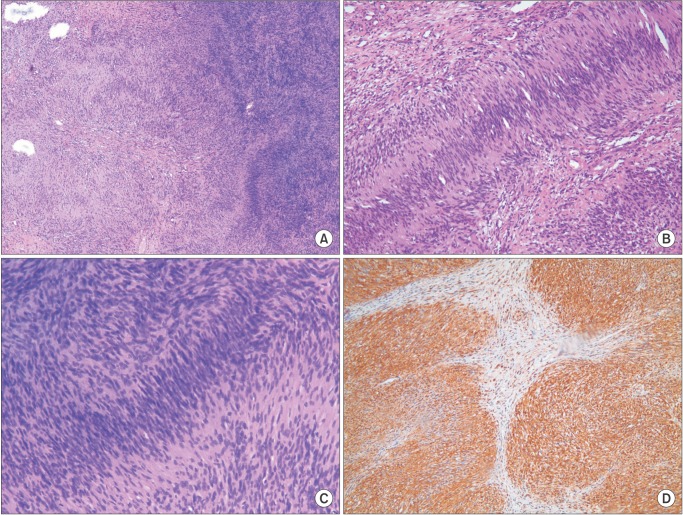

The microscopic appearance of the lesion was characterized by two patterns, Antoni A and Antoni B of neurilemmoma. Streaming fascicles of spindle-shaped Schwann cells surrounded a central acellular eosinophilic region of Verocay bodies in palisading patterns. This pattern represents Antoni A. The less cellular and less organized Antoni B pattern bordered the Antoni A pattern.(Fig. 7. A, 7. B) High cellularity was detected in the Antoni A pattern, but there was no evidence of dysplasia.(Fig. 7. C) Immunohistochemistry showed a diffuse positive reaction to the S-100 protein.(Fig. 7. D)

Neurilemmomas (schwannomas) are well-encapsulated, benign, slow-growing tumors that are usually solitary1. They originate from Schwann cells of the nerve sheath surrounding any cranial, peripheral, or autonomic nerve. Masses may be attached to the originating nerve or surrounded by the nerve2. Although the etiology of neurilemmomas remains unknown, it is postulated that the lesions arise through the proliferation of Schwann cells, compressing and displacing the surrounding nerve3.

Between 25% and 45% of all neurilemmomas occur in the head and neck region, and 20% of these lesions occur in the intraoral area. Intraoral neurilemmomas arise mainly from the tongue, followed by the palate, floor of mouth, buccal mucosa, gingiva, lips, and vestibular mucosa45. Neurilemmomas usually occur in the second or third decade of life, but can occur at any age. There is no definite sex predilection. Masses are typically between 0.5 to 3 cm in size, rarely exceeding 5 cm46.

Neurilemmomas show well-defined boundaries and appear homogeneous on CT images. When CT images show heterogeneous lesions, malignant changes in the neurogenic tumor may be suspected7. In T1-weighted MR images, the signals of the lesions are isointense to that of muscle, and hyperintense to that of muscle on T2-weighted images8. In this report, CT and MR imaging findings could not rule out the possibility of malignancy. Their rarity and variety of morphologic and radiologic features make the differential diagnosis of neurilemmoma difficult9. Histopathological features were used to make a definitive diagnosis.

Minor salivary gland tumors are rare, comprising 0.5% to 1% of all epithelial salivary gland tumors. However, 80% to 90% of all minor salivary gland tumors show malignancy10. The imaging features of low-grade malignant salivary gland lesions resemble those of benign salivary gland tumors11. Therefore, when dealing with sublingual area masses, clinicians should keep in mind the possibility of malignancy and sublingual gland tumor, though definitive diagnosis relies on histopathologic examination.

Microscopic evaluation of neurilemmoma shows two main patterns. The Antoni A pattern consists of densely-packed spindle cells. These cells are arranged in a typical, palisading figure surrounding acellular, eosinophilic areas known as Verocay bodies. The Antoni B pattern, the loose hypocellular arrangement, lies beside the Antoni A pattern. Positive staining for the neural crest marker, S-100 protein, is an important characteristic for diagnosis61213. The tumor in our patient showed characteristics typical of neurilemmoma.

Identifying the originating nerve may be difficult, as it is difficult to differentiate between tumors of the lingual, hypoglossal and glossopharyngeal nerves14. In this report, the tumor was infiltrated by a branch of the lingual nerve, a portion of which had to be sacrificed for complete excision of the mass. The patient complained of slight hypoesthesia on the tongue at the immediate postoperative appointment, but at a later follow up meeting the patient described little inconvenience. In cases requiring removal of a large portion of the innervating nerve, interposition nerve grafting or end-to-end anastomosis should be considered during the surgical procedure12.

The current treatment modality for neurilemmoma is complete surgical excision2. The intraoral approach avoids extraoral scarring and is preferred. However, in some cases, intraoral excision may not be adequate for complete removal of the mass. Incomplete surgical removal of a neurilemmoma may result in recurrence9. Transhyoid excision can be a cosmetic alternative. The choice of surgical approach is based on tumor size and location3. When the tumor is large and located somewhat posteriorly, a well-experienced surgeon can perform a submandibular visor flap. In comparison to the mandibular splitting technique, which provides excellent access, the visor flap allows good access with less cosmetic deformity6. We require informed consent concerning the possibility of requiring the extraoral visor flap approach before patients undergo general anesthesia. The intraoral approach remains the first choice to minimize postoperative complications, and in this case the whole mass could fortunately be removed by the intraoral approach alone. Once removed completely, neurilemmomas do not recur. The malignant transformation of neurilemmomas is rare15, with few cases reported16. Neurilemmomas are highly radio-resistant, and radiotherapy is not indicated for their management5.

References

1. Arda HN, Akdogan O, Arda N, Sarikaya Y. An unusual site for an intraoral schwannoma: a case report. Am J Otolaryngol. 2003; 24:348–350. PMID: 13130451.

2. Naik SM, Goutham MK, Ravishankara S, Appaji MK. Sublingual Schwannoma: a rare clinical entity reported in a hypothyroid female. Int J Head Neck Surg. 2012; 3:33–39.

3. Hsu YC, Hwang CF, Hsu RF, Kuo FY, Chien CY. Schwannoma (neurilemmoma) of the tongue. Acta Otolaryngol. 2006; 126:861–865. PMID: 16846930.

4. Tsushima F, Sawai T, Kayamori K, Okada N, Omura K. Schwannoma in the floor of the mouth: a case report and clinicopathological studies of 10 cases in the oral region. J Oral Maxillofac Surg Med Pathol. 2012; 24:175–179.

5. Gallo WJ, Moss M, Shapiro DN, Gaul JV. Neurilemoma: review of the literature and report of five cases. J Oral Surg. 1977; 35:235–236. PMID: 264530.

6. de Bree R, Westerveld GJ, Smeele LE. Submandibular approach for excision of a large schwannoma in the base of the tongue. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2000; 257:283–286. PMID: 10923945.

7. Cohen LM, Schwartz AM, Rockoff SD. Benign schwannomas: pathologic basis for CT inhomogeneities. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1986; 147:141–143. PMID: 3487205.

8. La'porte SJ, Juttla JK, Lingam RK. Imaging the floor of the mouth and the sublingual space. Radiographics. 2011; 31:1215–1230. PMID: 21918039.

9. AL-Alawi YSM, Kolethekkat AA, Saparamadu PAM, Al Badaai Y. Sublingual gland schwannoma: a rare case at an unusual site. Oman Med J. 2014; 29:DOI: 10.5001/omj.2014.41.

10. Rinaldo A, Shaha AR, Pellitteri PK, Bradley PJ, Ferlito A. Management of malignant sublingual salivary gland tumors. Oral Oncol. 2004; 40:2–5. PMID: 14662408.

11. Lee YY, Wong KT, King AD, Ahuja AT. Imaging of salivary gland tumours. Eur J Radiol. 2008; 66:419–436. PMID: 18337041.

12. Laviv A, Faquin WC, August M. Schwannoma (neurilemmoma) in the floor of the mouth: Presentation of two cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg Med Pathol. 2015; 27:199–203.

13. Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM, Bouquot JE. Oral and maxillofacial pathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders;2002. p. 456–457.

14. Enoz M, Suoglu Y, Ilhan R. Lingual schwannoma. J Cancer Res Ther. 2006; 2:76–78. PMID: 17998681.

15. Dreher A, Gutmann R, Grevers G. Extracranial schwannoma of the ENT region. Review of the literature with a case report of benign schwannoma of the base of the tongue. HNO. 1997; 45:468–471. PMID: 9324502.

16. Daimaru Y, Hashimoto H, Enjoji M. Malignant peripheral nervesheath tumors (malignant schwannomas). An immunohistochemical study of 29 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1985; 9:434–444. PMID: 3937453.

Fig. 2

Computed tomography showing a heterogeneous enhancing lesion. A. Axial view. B. Coronal view. The artifact was seen through all cuts.

Fig. 3

T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging showing a well-defined heterogeneous lesion. A. Axial view. B. Coronal view.

Fig. 4

T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging showing a well-defined heterogeneous lesion. A. Axial view. B. Coronal view.

Fig. 5

Perioperative clinical photograph. A. The mass was removed through an intraoral approach. B. The mass was well-encapsulated and removed as a whole.

Fig. 6

Postoperative photograph of main mass. A. The mass was well-encapsulated and ovoid in shape. B. Upon dissection of the mass, many exophytic lobules were detected.

Fig. 7

Microscopic examination of the mass. A. Antoni B pattern with less cellularity, left. Antoni A pattern with well-organized, high cellularity, right (H&E staining, ×40). B. Streaming fascicles of spindle-shaped Schwann cells surround a central acellular, eosinophilic region of Verocay bodies (H&E staining, ×100). C. Magnification of the Antoni A area shows no evidence of cellular dysplasia in spite of high cellularity (H&E staining, ×100). D. Immunohistochemistry shows reactivity to S-100 protein (×100).

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download