Abstract

The two main forms of myositis ossificans are congenital and acquired. Either form is rare in the head and neck region. The acquired form is often due to trauma, with bullying as a fairly common cause. This report of myositis ossificans of the platysma in an 11-year-old female patient emphasizes the need for a high index of suspicion in unexplainable facial swellings in children and the benefit of modern investigative modalities in their management.

Myositis ossificans (MO) is a rare and pathological heterotopic deposition of bone in striated muscle, tendon, ligament, fascia, and aponeurosis. Generally, the two main forms are congenital (MO progressiva) and acquired, which is described as traumatic MO (also referred to as MO circumscripta) or non-traumatic MO. The congenital form was first described around 16701. While the non-neoplastic, progressive ossification of soft tissues due to a congenital etiology results in early mortality from respiratory compromise, some acquired forms also result in serious morbidity due to inadequate treatment options123.

In the head and neck region, MO has involved muscles such as the temporalis, masseter, buccinator, sternocleidomastoid, trapezius, and platysma45. The soft tissues of the myocardium, diaphragm, tongue, larynx, smooth muscles, and sphincters are spared calcification in MO. MO progressiva appears in childhood as an autosomal dominant condition with irregular penetrance where ectopic bone formation can occur at any age, but particularly occurs between birth and 10 years of age. This genetic anomaly is the most extreme manifestation of MO and consists of skeletal abnormalities, including microdactyly of the first digits, exostosis, and the absence of the two upper incisors6. While MO can occur in either sex, the acquired forms are uncommon in children. Micheli et al.7 reported that only 57 cases of pediatric traumatic MO have been identified. Traumatic MO involving the platysma is exceedingly rare. The most recent report of the condition in the platysma involved an adult patient who had previous radical neck dissection8. We have found no previous report of traumatic MO of the platysma in a child. This paper presents a case of traumatic MO of the platysma in an 11-year-old female patient to illustrate the associated management challenges in a resource-constrained setting.

An 11-year-old female patient was admitted to the Military Hospital (Lagos, Nigeria) through the Casualty Department on referral from a boarding school on account of dysphagia to solids and very painful submandibular swelling of 3 days duration. She denied a history of trauma to the area and the symptoms were not affected by the smell or sight of food. There was no obvious dental cause of the swelling and Wharton's duct was patent. Due to the severity of the symptoms, she was hospitalized on the presumptive diagnosis of acute sialedenitis and started on intravenous ceftriaxone 40 mg/kg body weight every 12 hours for 3 days and intramuscular acetaminophen 480 mg every 8 hours for 3 days. Other likely diagnoses considered were acute submandibular space infection and infected sialolithiasis. Consultation with the otorhinolaryngologist found no ear, nose, or throat causes for her dysphagia. On the third day of admission, the dysphagia and pain had subsided, allowing for better clinical examination that revealed a mobile, irregularly-shaped, tender left submandibular mass.(Fig. 1) Bimanual palpation did not suggest the presence of stones in the submandibular gland or ducts. The intravenous antibiotics were continued for another 4 days. The patient was discharged home on the seventh day of admission. Plain posterior-anterior radiograph and occlusal radiograph of the lower jaw showed no abnormalities. Ultrasonography of the left submandibular region revealed two irregular, well circumscribed hypoechoic lobulated masses measuring 13.2 mm by 10 mm and 15.2 mm by 14.4 mm in dimension, with slight posterior enhancement but no calcification.(Fig. 2) The presumptive diagnosis by the sonologist was malignant tumor of the submandibular gland with the recommendation of further imaging studies, followed by excision of the mass for histopathologic examination. Further imaging, such as computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), was not done as they were not affordable for the parent. By the tenth day of consultation, there was very little resolution of the mass, which was mobile but diffuse, and thus the initial presumptive diagnoses were all ruled out. A probable mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the submandibular gland was suspected and the parent was advised to allow for excisional biopsy of the gland.

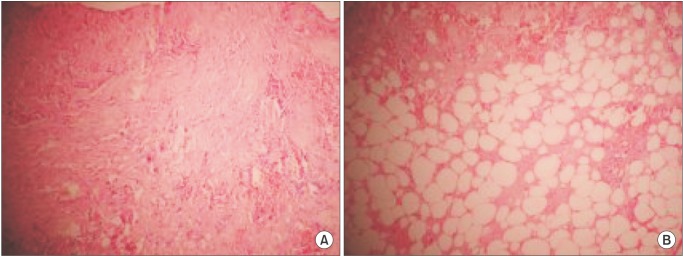

After routine pre-surgical work-up for general anesthesia, a left submandibular incision was made on the skin. After reflecting the investing layer of the deep cervical fascia, the platysma was felt to be gritty on palpation and to the surgical knife, and a portion was excised for histopathology. Further palpation in the region yielded no other masses, so the submandibular gland was left undisturbed. The wound was closed. The tissue histology revealed necrotic hemorrhagic skeletal muscle fibers with mature lipocytes, focal dystrophic calcification, and acellular debris.(Fig. 3) The final diagnosis was traumatic MO of the platysma. When presented with the diagnosis, the patient admitted to traumatic injury to the submandibular region due to bullying by seniors from her boarding house, but no specific duration was given. The parents chose to transfer the child to another school and postoperative review after 6 months showed complete resolution of the symptoms and good wound healing. Informed consent was obtained from the mother for this report.

Traumatic MO accounts for almost 75% of MO in the literature9. The other forms of MO are MO progressiva and non-traumatic MO. Schajowicz10 stated that while non-traumatic MO occurs in association with neuromuscular diseases, tetanus, poliomyelitis, and burns, some causes could be idiopathic. Traumatic MO occurs more commonly in males than in females, possibly due to the relatively higher exposure of males to trauma. About 80% of cases reportedly arise in the large muscles of the extremities (e.g., quadriceps muscle or brachialis muscle)11, and occurrence in the head and neck region is uncommon. The association of TMO with trauma remains controversial101213. Although some authors deny such an association, a history of prior trauma, often associated with sports injuries, is reported in around 60% to 75% of patients10. Sodl et al.14 reported that fraternity hazing and other forms of school bullying could cause traumatic MO. Apart from sport-related injuries, minor to severe local trauma, such as the striking of the cheeks, fractures of the jaws, and falling off a horse, have been reported to be causes of traumatic MO in the muscles of mastication4. This case report is possibly the second report of involvement of the platysma and the first case of traumatic MO of the platysma due to bullying reported in the literature. The case of TMO described by Shugar et al.8 was attributed to surgical trauma to the platysma muscle during radical neck dissection. Worldwide, the magnitude of the effects of hazing and bullying in schools may never be known. Our patient only volunteered the traumatic cause of her injuries when presented with the histologic diagnosis. Refusal to volunteer a history of bullying could be due to the fear of retribution, shame, or a desire to protect the perpetrator(s). There is a need for collaborative surveillance involving parents, school teachers, and physicians to detect and eliminate the dangerous practice of hazing and bullying from schools.

MO often starts as a non-specific painful soft tissue mass that could be mistaken for an infection or a soft tissue tumour15. In non-traumatic MO, the predisposing illness is fairly obvious, while in traumatic MO, early cases could still contain hematomas detectable on diagnostic ultrasound. This would indicate a traumatic origin and assist in differential diagnosis16. Our patient had severe painful submandibular swelling with dysphagia. The elimination of a dental etiology and the initial denial of trauma made salivary gland infection, stones, and tumors high on the differential diagnoses. Localization of the submandibular swelling after resolution of the acute phase and further clinical examination showing slight left submandibular swelling (Fig. 1) ruled out salivary gland infection as the diagnosis. Sialolithiasis could be confused with traumatic MO, even when no stones are palpable in the gland or duct, and remained a possibility until surgery. Traumatic MO of the platysma was not considered due to its rarity and the denial of a history of trauma to that part of the body.

Imaging modalities such as plain radiographs, ultrasound, scintigraphy, CT and MRI have been extensively used to elucidate the diagnosis and monitor the treatment of traumatic MO. According to reports, plain radiography shows a soft tissue swelling and faint peripheral calcification in the early stages of traumatic MO (less than 2-4 weeks) followed by well-defined calcification in the middle stages (5-24 weeks) that may be associated with coarser, central calcification. The fully matured traumatic MO (>6 months) is densely calcified and usually lies parallel to the long axis of the adjacent bone1718. Plain radiographs of the submandibular region in our patient showed no anomalies, probably because the lesion was located in the platysma, which is a thin muscle, as well as the lesion's early stage of development 4 weeks after the injury. This reinforces the need to utilize multiple imaging methods to facilitate clinical management.

Wang et al.16 stated that ultrasonography of traumatic MO reveals a hypoechoic mass with a central reflective core with sheet-like (lamellar) hyper-reflectivity at the periphery of the mass in the early lesion, more reflective areas in the intermediate lesion, and diffuse reflective areas in the late (mature) lesion. The ultrasonographic image shown in Fig. 2 consists of two irregular, hypoechogenic masses, resulting in the inaccurate suspicion of a malignant tumor of the submandibular gland. It is possible that a central reflective core of calcification was identifiable by Wang et al.16 because they studied larger muscle masses such as the quadriceps, and this characteristic may not be identifiable in the thin platysma muscle. In addition, the sensitivity of the ultrasound equipment used could also affect the ability to demonstrate this feature in early cases of MO. The importance of modern equipment in diagnosis and treatment cannot be over-emphasized; however, several factors limit their accessibility in resource-poor countries such as Nigeria.

Using scintigraphy, Wang et al.16 reported that early traumatic MO shows mildly increased uptake to marked soft-tissue accumulation of tracer, while on CT scan, it shows an enlarged muscle group with normal attenuation with or without faint calcification within the lesion. Scintigraphy of the intermediate lesions shows a progressive decrease in radiotracer uptake while the CT scan shows zonal phenomenon characterized by a rim of calcification with varying thickness at the periphery and a central area with the same attenuation as normal muscle. In the late lesion, scintigraphy shows mild or normal uptake while the CT scan shows a heavily calcified lesion16. Though not routine, MRI could compliment plain radiographs by better defining hard and soft tissue structures. Our hospital had no facilities for scintigraphy, CT, and MRI, and the parent could not afford the cost in private hospitals. It is noteworthy that traumatic MO has no pathognomonic appearance on imaging and the diagnosis depends on an adequate and reliable history, followed by appropriate clinical examination.

Chuah et al.19 reported that the erythrocyte sedimentation rate and alkaline phosphatase could be elevated in the acute phase of traumatic MO. While these tests were not carried out in this patient, they are non-specific with wide variations based on age and sex, especially the alkaline phosphatase levels found in growing children20 such as this 11-year-old girl. The microscopic appearance of traumatic MO depends on the stage of the lesion. The early lesion shows immature osteoblasts and proliferating fibroblasts, as described by Micheli et al.7. In the intermediate lesion, dystrophic calcification and necrotic haemorrhagic skeletal muscle could be found, as seen in our patient.(Fig. 3) In the late stage, lamellar bone delimited by osteoblasts can be seen5.

There is considerable controversy regarding the optimum timing and treatment for traumatic MO. Shugar et al.8 suggested that because of the risk of recurrence, the abnormal bone formed in the platysma should be removed only if there are significant associated symptoms. Such surgery should be delayed for 6 to 12 months following the traumatic episode to allow for maturation because lesional immaturity could be a contributory factor to recurrence. Hanquinet et al.21 presented the cases of two children with traumatic MO of the arm. In their opinion, while the lesion could spontaneously resolve, surgery could be done to remove some tissue for diagnosis if typical calcification is not observed in the mature lesion. In the 16-year-old patient studied by Russo et al.22, the traumatic MO was associated with severe pain, although there was no radiologic evidence of calcification. Surgical excision of the involved muscle resulted in immediate resolution of symptoms. These authors believe that waiting for complete maturation of the lesion may not be necessary in the presence of severe symptoms. Our patient had surgical excision of a portion of the involved platysma muscle with complete resolution of the symptoms within 6 months. Conservative measures such as rest, analgesics, physical therapy, and extracorporeal shock wave therapy have been satisfactorily used in other non-facial body parts1923. It is possible that following the diagnosis of traumatic MO, surgery can be delayed if symptoms are not severe. Extensive excision of the early lesion is not indicated especially as clear lesional boundaries are often not discernible. Given the intra-operative findings of a gritty nature of the platysma in our patient, the minimal tissue removed did not affect the resolution of symptoms. In early cases of traumatic MO, excision of the entire muscle is potentially not necessary. Rather, minimal surgery should be augmented by rest and analgesic therapy.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the participation of Drs. Lillian Ahaji and Olaitan Nwankwo in the care of this patient.

References

1. Fletcher E, Moss MS. Myositis ossificans progressiva. Ann Rheum Dis. 1965; 24:267–272. PMID: 14297341.

2. Bar Oz B, Boneh A. Myositis ossificans progressiva: a 10-year follow-up on a patient treated with etidronate disodium. Acta Paediatr. 1994; 83:1332–1334. PMID: 7734885.

3. Lungu SG. Myositis ossificans: two case presentations. Med J Zambia. 2011; 38:25–31.

4. Kruse AL, Dannemann C, Grätz KW. Bilateral myositis ossificans of the masseter muscle after chemoradiotherapy and critical illness neuropathy: report of a rare entity and review of literature. Head Neck Oncol. 2009; 1:30. PMID: 19674466.

5. Man SC, Schnell CN, Fufezan O, Mihut G. Myositis ossificans traumatica of the neck: a pediatric case. Maedica (Buchar). 2011; 6:128–131. PMID: 22205895.

6. Bridges AJ, Hsu KC, Singh A, Churchill R, Miles J. Fibrodysplasia (myositis) ossificans progressiva. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1994; 24:155–164. PMID: 7899873.

7. Micheli A, Trapani S, Brizzi I, Campanacci D, Resti M, de Martino M. Myositis ossificans circumscripta: a paediatric case and review of the literature. Eur J Pediatr. 2009; 168:523–529. PMID: 19130083.

8. Shugar MA, Weber AL, Mulvaney TJ. Myositis ossificans following radical neck dissection. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1981; 90:169–171. PMID: 7224517.

9. Patel S, Richards A, Trehan R, Railton GT. Post-traumatic myositis ossificans of the sternocleidomastoid following fracture of the clavicle: a case report. Cases J. 2008; 1:413. PMID: 19102776.

10. Schajowicz F. Tumours and tumour-like lesions of bone. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer;1994.

11. Nuovo MA, Norman A, Chumas J, Ackerman LV. Myositis ossificans with atypical clinical, radiographic, or pathologic findings: a review of 23 cases. Skeletal Radiol. 1992; 21:87–101. PMID: 1566115.

12. Booth DW, Westers BM. The management of athletes with myositis ossificans traumatica. Can J Sport Sci. 1989; 14:10–16. PMID: 2647253.

13. Kransdorf MJ, Meis JM, Jelinek JS. Myositis ossificans: MR appearance with radiologic-pathologic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1991; 157:1243–1248. PMID: 1950874.

14. Sodl JF, Bassora R, Huffman GR, Keenan MA. Traumatic myositis ossificans as a result of college fraternity hazing. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008; 466:225–230. PMID: 18196398.

15. Hanna SL, Magill HL, Brooks MT, Burton EM, Boulden TF, Seidel FG. Cases of the day. Pediatric. Myositis ossificans circumscripta. Radiographics. 1990; 10:945–949. PMID: 2217980.

16. Wang XL, Malghem J, Parizel PM, Gielen JL, Vanhoenacker F, De Schepper AM. Pictorial essay. Myositis ossificans circumscripta. JBR-BTR. 2003; 86:278–285. PMID: 14651084.

17. Resnick D, Niwayama G. Soft tissues. In : Resnick D, editor. Diagnosis of bone and joint disorders. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders;1995. p. 4491–4622.

18. Tyler P, Saifuddin A. The imaging of myositis ossificans. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol. 2010; 14:201–216. PMID: 20486028.

19. Yu Chuah T, Loh TP, Loi HY, Lee KH. Myositis ossificans. West J Emerg Med. 2011; 12:371. PMID: 22224121.

20. Turan S, Topcu B, Gökçe İ, Güran T, Atay Z, Omar A, et al. Serum alkaline phosphatase levels in healthy children and evaluation of alkaline phosphatase z-scores in different types of rickets. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol. 2011; 3:7–11. PMID: 21448327.

21. Hanquinet S, Ngo L, Anooshiravani M, Garcia J, Bugmann P. Magnetic resonance imaging helps in the early diagnosis of myositis ossificans in children. Pediatr Surg Int. 1999; 15:287–289. PMID: 10370048.

22. Russo R, Hughes M, Manolios N. Biopsy diagnosis of early myositis ossificans without radiologic evidence of calcification: success of early surgical resection. J Clin Rheumatol. 2010; 16:385–387. PMID: 21085015.

23. Torrance DA, Degraauw C. Treatment of post-traumatic myositis ossificans of the anterior thigh with extracorporeal shock wave therapy. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2011; 55:240–246. PMID: 22131560.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download