I. Introduction

Surgical extraction of an impacted mandibular third molar is common, and an impacted third molar is one of the most investigated topics in oral and maxillofacial surgery. Extraction in these cases can result in sequelae and complications including pain, swelling, infection, and nerve injury, because the procedure requires incision, bone removal, tooth separation, and closure

1. The procedure can be difficult for the patient and challenging for the surgeon if proper evaluation of the impacted tooth is not performed before extraction. It is essential to thoroughly evaluate extraction difficulty and to fully inform the patient of the potential challenges.

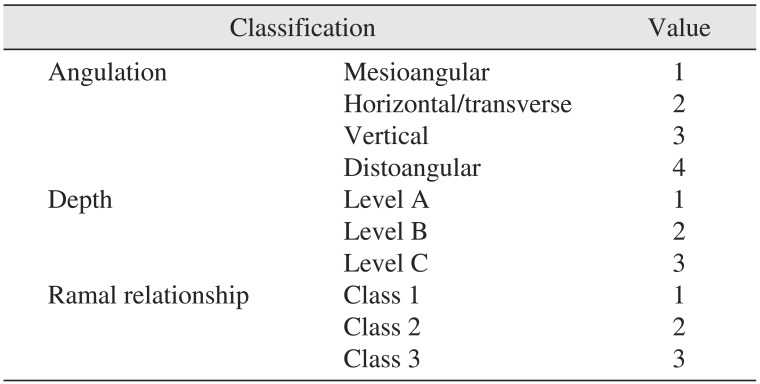

Several methods have been proposed for preoperative evaluation of difficulty in surgical extraction. The Pell-Gregory classification

2 was reported in 1933 and has been widely cited in oral and maxillofacial surgery articles. The classification establishes nine groups of impacted lower third molars using level of impaction and ramal relationship but does not consider angulation of impacted teeth as included in the Pederson scale, another prominent measure. The usefulness of Pell-Gregory classification has been questioned, and García et al.

2 maintained that the classification is not reliable for extraction difficulty prediction, even in vertical impaction.

Winter's classification

3, another system of impacted lower third molar classification, sorts impacted lower molars according to axis angulation as mesioangular, vertical, horizontal, and distoangular impactions. The Pederson index predicts surgical extraction difficulty using both Pell-Gregory classification and Winter's classification. Unlike Pell-Gregory classification, the Pederson index

4 includes angulation factor, although some studies and analyses have concluded that it is not a reliable test for predicting surgical difficulty of third molar surgery and should not be employed as a sole instrument for preoperative assessment of difficulty

456.

Because these prediction methods consider only the position of teeth in radiographs and exclude factors of age, body mass index (BMI), root morphology, bone quality, and proximity to mandibular canal, which affect surgical extraction difficulty, surgeons can experience difficulties outside of the classifications and index system.

In this study, level of difficulty, presumed causes of difficulty, demographic factors, clinical factors, and radiographic findings were assessed, compared, and analyzed in order to identify very difficult surgical extraction cases.

Go to :

III. Results

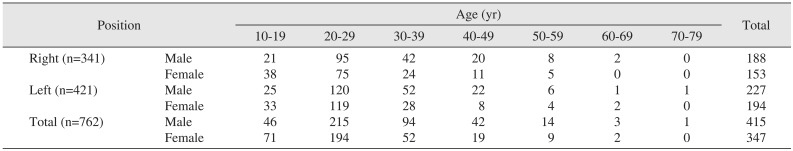

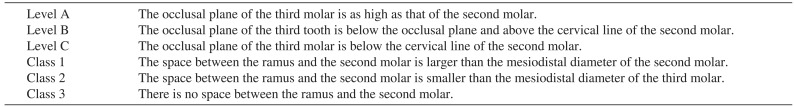

The demographic data are shown in

Table 3.

Table 3

Distributions of age, position, and sex

|

Position |

Age (yr) |

Total |

|

10-19 |

20-29 |

30-39 |

40-49 |

50-59 |

60-69 |

70-79 |

|

Right (n=341) |

Male |

21 |

95 |

42 |

20 |

8 |

2 |

0 |

188 |

|

Female |

38 |

75 |

24 |

11 |

5 |

0 |

0 |

153 |

|

Left (n=421) |

Male |

25 |

120 |

52 |

22 |

6 |

1 |

1 |

227 |

|

Female |

33 |

119 |

28 |

8 |

4 |

2 |

0 |

194 |

|

Total (n=762) |

Male |

46 |

215 |

94 |

42 |

14 |

3 |

1 |

415 |

|

Female |

71 |

194 |

52 |

19 |

9 |

2 |

0 |

347 |

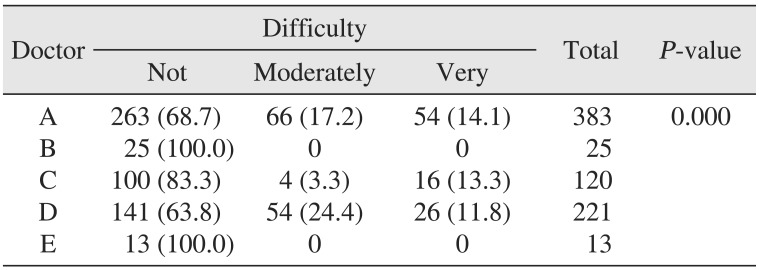

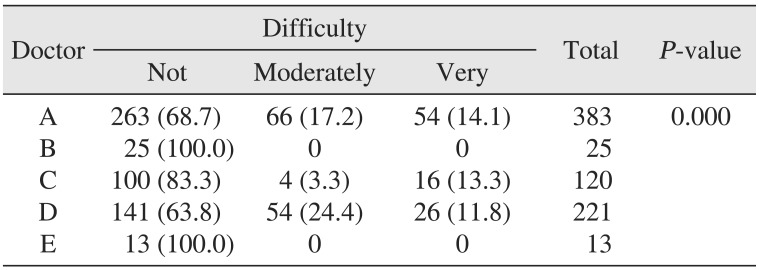

Among 762 extractions, 542 were not difficult (71.1%), 124 were moderately difficult (16.3%), and 96 were very difficult (12.6%). The distribution of difficulties by operators is shown in

Table 4, and the proportion of difficulty groups was different among operators (

P=0.000).

Table 4

Distribution of difficulties by operator

|

Doctor |

Difficulty |

Total |

P-value |

|

Not |

Moderately |

Very |

|

A |

263 (68.7) |

66 (17.2) |

54 (14.1) |

383 |

0.000 |

|

B |

25 (100.0) |

0 |

0 |

25 |

|

C |

100 (83.3) |

4 (3.3) |

16 (13.3) |

120 |

|

D |

141 (63.8) |

54 (24.4) |

26 (11.8) |

221 |

|

E |

13 (100.0) |

0 |

0 |

13 |

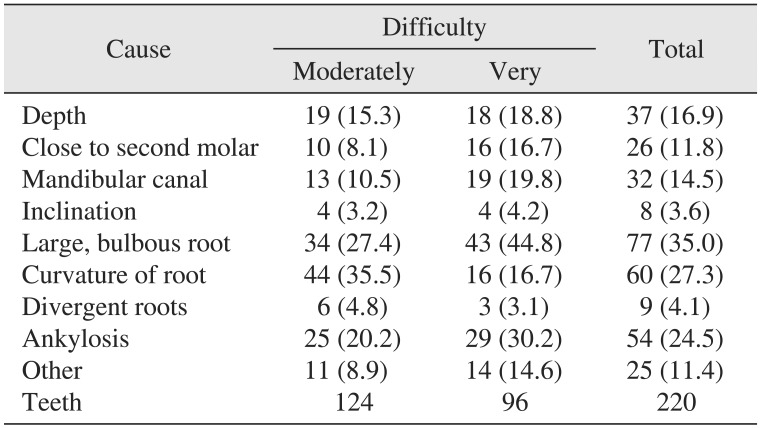

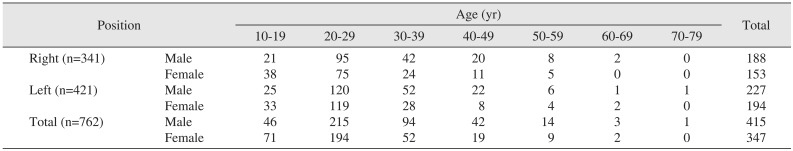

Presumed causes of difficult extraction in order of frequency were large and/or bulbous root, root curvature, and ankylosis. There were 103 position-related causes and 200 root-related causes. The average number of causes in moderately-difficult cases was 1.34, while that of very-difficult cases was 1.69.(

Table 5)

Table 5

The prevalence of presumed causes of difficult extraction

|

Cause |

Difficulty |

Total |

|

Moderately |

Very |

|

Depth |

19 (15.3) |

18 (18.8) |

37 (16.9) |

|

Close to second molar |

10 (8.1) |

16 (16.7) |

26 (11.8) |

|

Mandibular canal |

13 (10.5) |

19 (19.8) |

32 (14.5) |

|

Inclination |

4 (3.2) |

4 (4.2) |

8 (3.6) |

|

Large, bulbous root |

34 (27.4) |

43 (44.8) |

77 (35.0) |

|

Curvature of root |

44 (35.5) |

16 (16.7) |

60 (27.3) |

|

Divergent roots |

6 (4.8) |

3 (3.1) |

9 (4.1) |

|

Ankylosis |

25 (20.2) |

29 (30.2) |

54 (24.5) |

|

Other |

11 (8.9) |

14 (14.6) |

25 (11.4) |

|

Teeth |

124 |

96 |

220 |

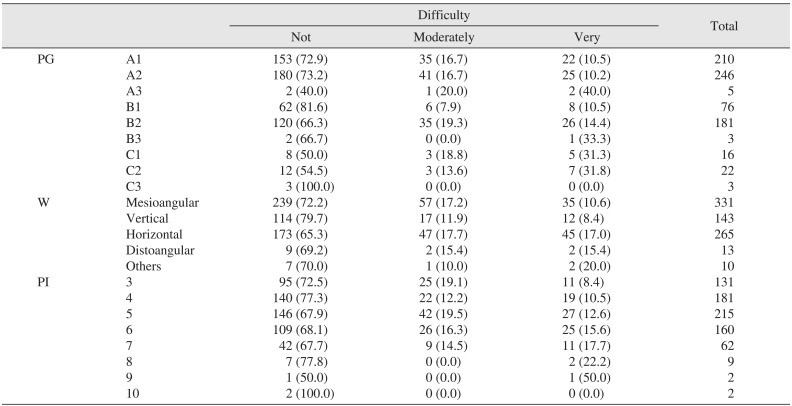

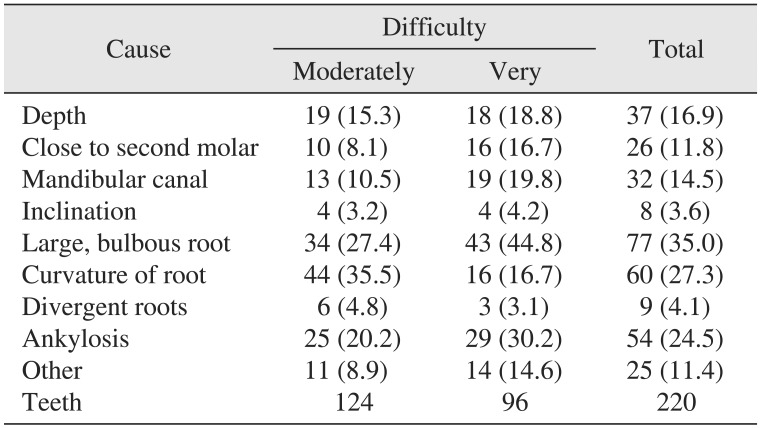

Using Pell-Gregory classification, B2 had the highest frequency and relatively high probability of difficult extraction. Using Winter's classification, horizontal impaction was the most difficult and showed the largest frequency of difficult extractions.(

Table 6)

Table 6

Pell-Gregory classification, Winter's classification, Pederson index, and extraction difficulty

|

Difficulty |

Total |

|

Not |

Moderately |

Very |

|

PG |

A1 |

153 (72.9) |

35 (16.7) |

22 (10.5) |

210 |

|

A2 |

180 (73.2) |

41 (16.7) |

25 (10.2) |

246 |

|

A3 |

2 (40.0) |

1 (20.0) |

2 (40.0) |

5 |

|

B1 |

62 (81.6) |

6 (7.9) |

8 (10.5) |

76 |

|

B2 |

120 (66.3) |

35 (19.3) |

26 (14.4) |

181 |

|

B3 |

2 (66.7) |

0 (0.0) |

1 (33.3) |

3 |

|

C1 |

8 (50.0) |

3 (18.8) |

5 (31.3) |

16 |

|

C2 |

12 (54.5) |

3 (13.6) |

7 (31.8) |

22 |

|

C3 |

3 (100.0) |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

3 |

|

W |

Mesioangular |

239 (72.2) |

57 (17.2) |

35 (10.6) |

331 |

|

Vertical |

114 (79.7) |

17 (11.9) |

12 (8.4) |

143 |

|

Horizontal |

173 (65.3) |

47 (17.7) |

45 (17.0) |

265 |

|

Distoangular |

9 (69.2) |

2 (15.4) |

2 (15.4) |

13 |

|

Others |

7 (70.0) |

1 (10.0) |

2 (20.0) |

10 |

|

PI |

3 |

95 (72.5) |

25 (19.1) |

11 (8.4) |

131 |

|

4 |

140 (77.3) |

22 (12.2) |

19 (10.5) |

181 |

|

5 |

146 (67.9) |

42 (19.5) |

27 (12.6) |

215 |

|

6 |

109 (68.1) |

26 (16.3) |

25 (15.6) |

160 |

|

7 |

42 (67.7) |

9 (14.5) |

11 (17.7) |

62 |

|

8 |

7 (77.8) |

0 (0.0) |

2 (22.2) |

9 |

|

9 |

1 (50.0) |

0 (0.0) |

1 (50.0) |

2 |

|

10 |

2 (100.0) |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

2 |

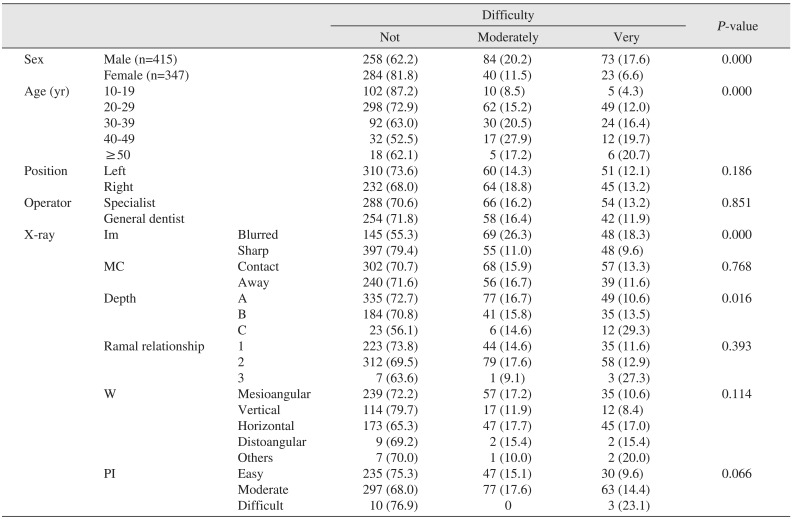

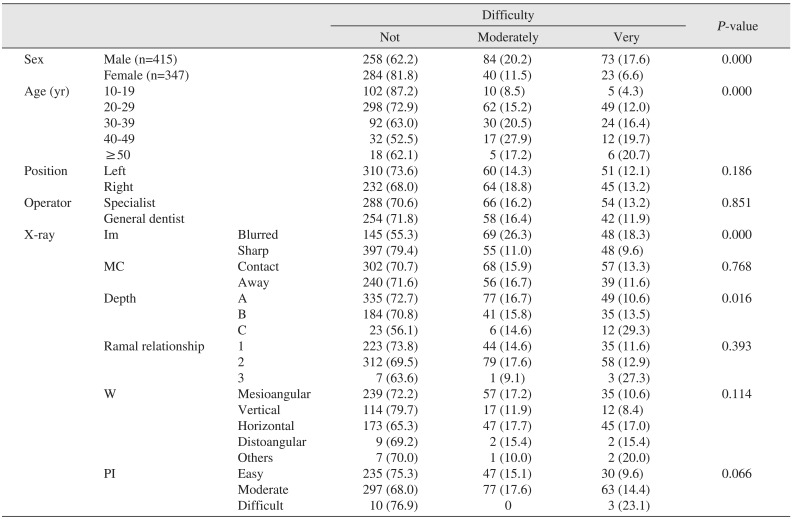

With regard to demographic factors, it was easier to extract impacted lower third molars in younger patients and in women than in older patients and men (

P=0.000). However, tooth position (right or left) was not associated with extraction difficulty (

P=0.186).(

Table 7)

Table 7

The relationships between extraction difficulty and demographic and radiographic variables

|

Difficulty |

P-value |

|

Not |

Moderately |

Very |

|

Sex |

Male (n=415) |

|

258 (62.2) |

84 (20.2) |

73 (17.6) |

0.000 |

|

Female (n=347) |

|

284 (81.8) |

40 (11.5) |

23 (6.6) |

|

Age (yr) |

10-19 |

|

102 (87.2) |

10 (8.5) |

5 (4.3) |

0.000 |

|

20-29 |

|

298 (72.9) |

62 (15.2) |

49 (12.0) |

|

30-39 |

|

92 (63.0) |

30 (20.5) |

24 (16.4) |

|

40-49 |

|

32 (52.5) |

17 (27.9) |

12 (19.7) |

|

≥50 |

|

18 (62.1) |

5 (17.2) |

6 (20.7) |

|

Position |

Left |

|

310 (73.6) |

60 (14.3) |

51 (12.1) |

0.186 |

|

Right |

|

232 (68.0) |

64 (18.8) |

45 (13.2) |

|

Operator |

Specialist |

|

288 (70.6) |

66 (16.2) |

54 (13.2) |

0.851 |

|

General dentist |

|

254 (71.8) |

58 (16.4) |

42 (11.9) |

|

X-ray |

Im |

Blurred |

145 (55.3) |

69 (26.3) |

48 (18.3) |

0.000 |

|

Sharp |

397 (79.4) |

55 (11.0) |

48 (9.6) |

|

MC |

Contact |

302 (70.7) |

68 (15.9) |

57 (13.3) |

0.768 |

|

Away |

240 (71.6) |

56 (16.7) |

39 (11.6) |

|

Depth |

A |

335 (72.7) |

77 (16.7) |

49 (10.6) |

0.016 |

|

B |

184 (70.8) |

41 (15.8) |

35 (13.5) |

|

C |

23 (56.1) |

6 (14.6) |

12 (29.3) |

|

Ramal relationship |

1 |

223 (73.8) |

44 (14.6) |

35 (11.6) |

0.393 |

|

2 |

312 (69.5) |

79 (17.6) |

58 (12.9) |

|

3 |

7 (63.6) |

1 (9.1) |

3 (27.3) |

|

W |

Mesioangular |

239 (72.2) |

57 (17.2) |

35 (10.6) |

0.114 |

|

Vertical |

114 (79.7) |

17 (11.9) |

12 (8.4) |

|

Horizontal |

173 (65.3) |

47 (17.7) |

45 (17.0) |

|

Distoangular |

9 (69.2) |

2 (15.4) |

2 (15.4) |

|

Others |

7 (70.0) |

1 (10.0) |

2 (20.0) |

|

PI |

Easy |

235 (75.3) |

47 (15.1) |

30 (9.6) |

0.066 |

|

Moderate |

297 (68.0) |

77 (17.6) |

63 (14.4) |

|

Difficult |

10 (76.9) |

0 |

3 (23.1) |

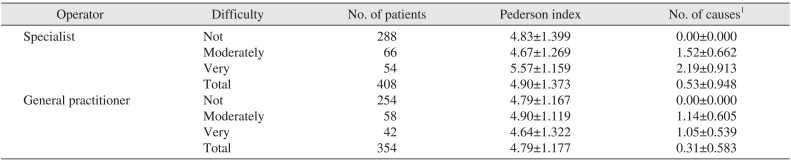

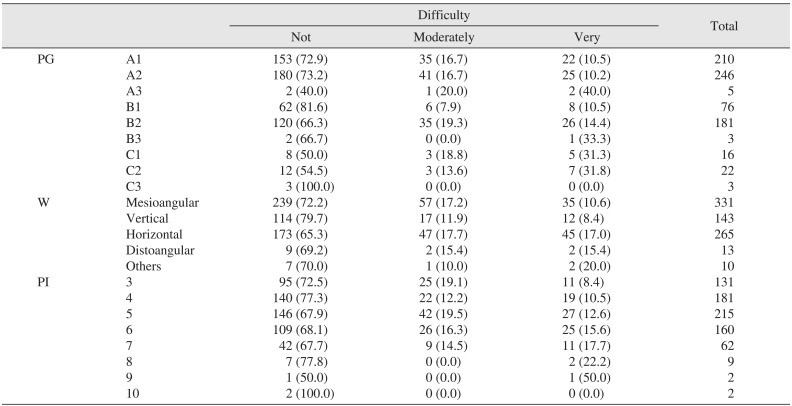

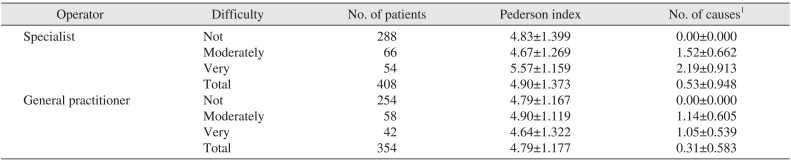

Whether or not the operator was a specialist did not influence difficulty (

P=0.851).(

Table 7) But the teeth that specialists extracted had higher Pederson index (

P=0.041) and more presumed causes of difficult extraction (

P=0.000).(

Table 8)

Table 8

Comparison of specialists' Pederson indexes and number of presumed causes of difficult extraction with those of general practitioners

|

Operator |

Difficulty |

No. of patients |

Pederson index |

No. of causes1

|

|

Specialist |

Not |

288 |

4.83±1.399 |

0.00±0.000 |

|

Moderately |

66 |

4.67±1.269 |

1.52±0.662 |

|

Very |

54 |

5.57±1.159 |

2.19±0.913 |

|

Total |

408 |

4.90±1.373 |

0.53±0.948 |

|

General practitioner |

Not |

254 |

4.79±1.167 |

0.00±0.000 |

|

Moderately |

58 |

4.90±1.119 |

1.14±0.605 |

|

Very |

42 |

4.64±1.322 |

1.05±0.539 |

|

Total |

354 |

4.79±1.177 |

0.31±0.583 |

On radiographic findings, teeth that had blurred image haziness (

P=0.000) or lower level of impaction (

P=0.016) were statistically associated with more difficult extraction. Relationship to mandibular canal (

P=0.768), ramal relationship (

P=0.393), Winter's classification (

P=0.114), and Pederson index (

P=0.066) were not associated with difficulty.(

Table 7)

Go to :

IV. Discussion

Most research on the difficulty of surgical extraction of impacted mandibular third molars has included demographic, clinical, and anatomical factors, with various results reported.

Among the demographic factors evaluated in this study, it was easier to extract impacted lower third molars in younger patients. Patient age has a demonstrated effect on the difficulty reported by operators, in agreement with previous studies

891011. The relevance of age to difficulty is likely attributable to the fact that it is easiest to surgically extract impacted lower third molar with roots formed from 1/3 to 2/3, and bone hardness and ankylosis increase with age.

In this study, operators experienced more difficulty when they extracted the impacted mandibular third molars of men than of women. This coincides with the results of other research that found that sex influences extraction difficulty

912. The large sizes of the crown and roots of men's third molars might explain the difference.

Whether or not the operator was a specialist did not make a difference in difficulty. However, in third molars that were extracted by specialists, the averages of Pederson index and number of presumed causes of difficult extraction were higher than in those of general practitioners. This might be the result of referring difficult cases to specialists. If this had been a randomized trial, the results could have been different.

For general practitioners, there was no difference in Pederson index among 3 difficulty groups; however, this index increased according to difficulty for specialists. The average of number of presumed causes of difficult extraction in the moderately difficult group was almost equal to that of very difficult group in general practitioners. However, in specialists, this average increased markedly from 1.52 to 2.19 in the very difficult group. These findings indicate that the anatomic condition of an impacted tooth does not influence the difficulty experienced by general practitioners, but does affect that of specialists. Inexperience rather than anatomy might be the main cause of difficult extraction for general practitioners.

After extraction, the operator judged the level of difficulty and the likely causes of the difficulty in extraction. The frequency order of causes was large and/or bulbous root, root curvature, and ankylosis, all of which are related to roots. Because root-related causes were twice as numerous as position-related causes, it seems clear that classification methods of impacted lower third molars and difficulty predicting indices that only consider position will not be reliable.

In the very difficult group, the number of root curvatures decreased, and those of large and/or bulbous root and ankylosis increased. Large and/or bulbous root and ankylosis seem to greatly impact the difficulty of extraction. Increase in the number of presumed causes increased the perceived difficulty by the operator. Cases in which deep impaction accompanied a close relationship to the second molar, deep impaction was accompanied by ankylosis, ankylosis was accompanied by a close relationship to the second molar, deep impaction accompanied widely divergent roots, and ankylosis accompanied large and/or bulbous root were very difficult rather than moderately difficult. When deep impaction or ankylosis accompanied other causes, difficult surgical extraction was more likely.

Among radiographic variables, close relationship with the mandibular canal was not associated with difficult surgical extraction (P=0.768), although it is known that a close relationship with the mandibular canal can complicate surgical extraction. This proximity becomes a problem only when a root fracture develops in the vicinity of the canal. A small percentage of such root fractures seems to be the reason why close relationship with the mandibular canal was not statistically associated with difficult surgical extraction.

According to Pell-Gregory classification, the probability order of difficult extractions was C2, B2, and B3. Pell-Gregory classification sorts impacted lower third molars according to depth of impaction and ramal relation. This study considered the two factors separately and demonstrated that depth of impaction was statistically associated with extraction difficulty, while ramal relation has no association. This affirms the claim of Akadiri et al.

13 that depth of impaction is the singular most important determinant of surgical difficulty, and that operators do not consider it difficult to develop flaps, reduce bone, or separate teeth in the ramal area.

Using Winter's classification, the probability order of difficult extraction was horizontal, distoangular, mesioangular, and vertical impactions. This runs counter to the Pederson index, which regards vertical impaction as more difficult than mesioangular and horizontal impactions. This might be one reason to question the reliability of the Pederson index.

According to Pell-Gregory classification and Winter's classification, there was no difference between the probability of moderately difficult cases and that of very difficult cases in each class. Classification based on tooth position alone does not predict difficulty very well, and other causes, especially root-related causes, should be considered for a more robust prediction.

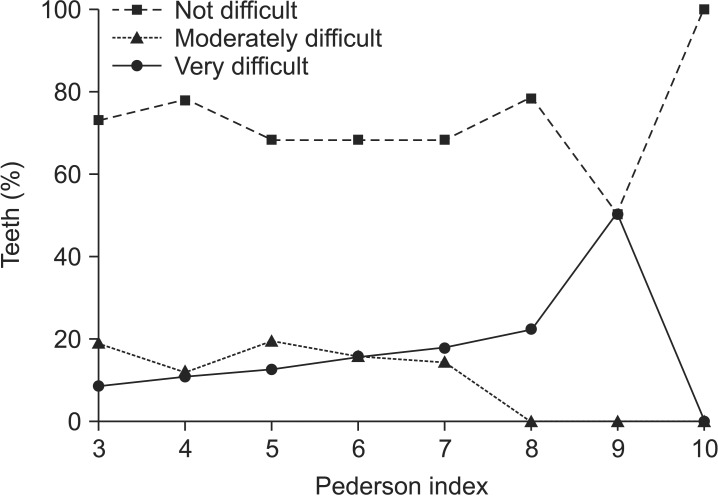

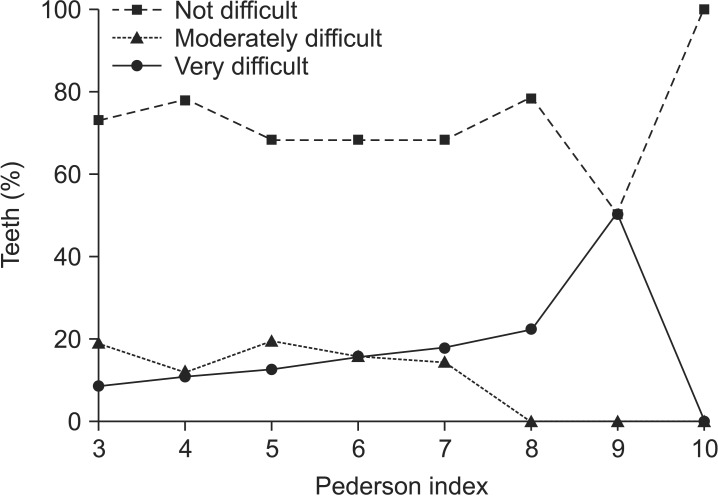

The Pederson index score was not proportional to difficulty in the moderately difficult group, but it was directly proportional to difficulty in the very difficult group.(

Table 6,

Fig. 1) This suggests that tooth position has a considerable effect on difficulty only when there are a large number of presumed causes. When the Pederson index score is low, other causes, except position-related causes, might not impact extraction difficulty. However, the operator should investigate the relation to the second molar, relation to the mandibular canal, root form, and ankylosis in order to distinguish very difficult cases when the index score is high. This confirms the study of Akadiri et al.

6, which posited that the Pederson index should not be employed as a sole instrument for preoperative assessment of difficulty in third molar surgery.

| Fig. 1Difficulty group distribution in Pederson index.

|

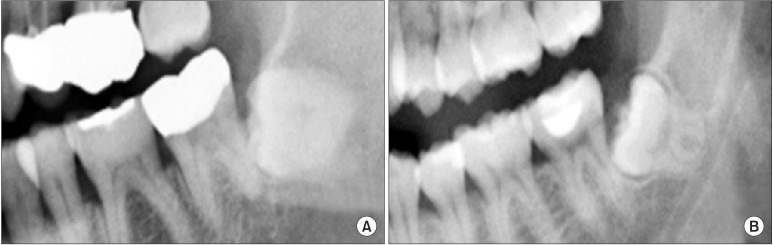

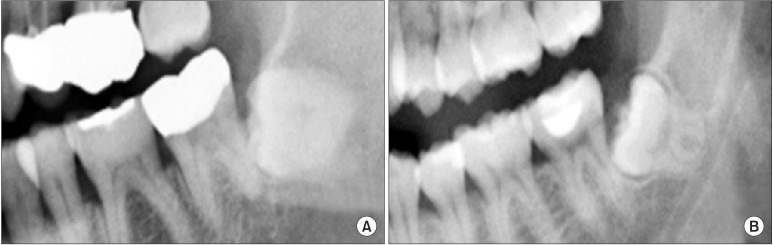

This study investigated the association between blurred panorama images and extraction difficulty.(

Fig. 2) The result was that blurred images were relevant to extraction difficulty. Radiography of an ankylosed tooth does not show a well-defined root or periodontal ligament space, which appears to fade into bone

14. In the absence of ankylosis, blurred images can result when the object drops out of the focal trough or the roots are overlapped with one another. It is assumed that large and/or bulbous roots and widely divergent roots are such cases and can increase extraction difficulty.

| Fig. 2Two types of radiographic images. A. A panoramic image that shows blurred root image and indistinct border. B. A panoramic image that shows relatively clear root anatomy and sharp border.

|

There are many factors that influence difficulty in surgical extraction of impacted mandibular third molars. Age, BMI, body surface area, ethnicity, operator experience, method, number of extracted teeth, depth of impaction, ramal relation, angulation of tooth, development of root, root curvature, relationship to the mandibular canal, width of root, patient anxiety, and other factors are thought to impact extraction difficulty, although there is disagreement among researchers about their relative impacts

891011121315161718.

The existing Pell-Gregory classification, Winter's classification, and Pederson index have proven unreliable, and newly developed classifications and difficulty prediction methods are overly complex or unreliable

7192021. The presence of many factors and disagreement among researchers make it very challenging to design a new practical and reliable predictor of surgical extraction difficulty.

In this study, the distribution of difficulty groups by operator showed significant differences.(

Table 4) This could be the result of different operator's criterion of difficulty and/or proportion of difficult extractions. All cases of two operators (one specialist and one general practitioner) were classified into the not difficult group by the criteria for classification. This might be a limit of the retrospective study. However, it does not seem problematic, because the proportion of their cases was very small (5.0%), and the objective of this study was to identify impactful factors not the ratio of difficult extractions.

There are many factors that are not objective or quantifiable in a surgical extraction difficulty study. Therefore, some researchers

1518 have used subjective methods in their studies. In this retrospective study, the subjective decision of the operator was used as a variable. Additional studies are necessary to verify the findings of this study.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download