Abstract

Although pathophysiology, incidence, and factors associated with the development of bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (BRONJ) and management strategies for patients treated with bisphosphonates or patients with BRONJ are well-established, few guidelines or recommendations are available for patients with a history of successfully healed BRONJ. We present a case of successful dental implant treatment after healing of BRONJ in the same region of the jaw, and speculate that implant placement is possible after healing of BRONJ surgery in select cases.

Bisphosphonates have been used to treat bony sequelae of malignant diseases such as multiple myeloma, metastatic diseases such as breast cancer, and osteoporosis1.

Patients receiving oral bisphosphonate therapy are at considerably low risk of bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (BRONJ). BRONJ adversely affects the quality of life, producing significant morbidity in afflicted patients2. The American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons (AAOMS) developed a task force to provide the best recommendations to clinicians for the management of BRONJ23. Furthermore, many articles and textbooks dealing with the pathophysiology, incidence, and factors associated with the development of BRONJ and management strategies for patients treated with bisphosphonates or patients with BRONJ have been published4567. Unfortunately, few guidelines or recommendations have been released for patients with history of successfully healed BRONJ8.

Generally, the placement of implants in patients with a history of successfully healed BRONJ is not recommended because patients who have already experienced BRONJ are at high risk of implant failure even though this conclusion is based on empirical data and not scientific evidence8.

We present a case of successful dental implant treatment after successful healing of BRONJ in the same region.

In March 2013, a 73-year-old female patient was referred to our clinic complaining of painful gingival and facial swelling at the left upper canine and first premolar area that began six months prior. Three dental implants had been placed in the left upper canine, first premolar, and first molar area at a private clinic three years earlier.

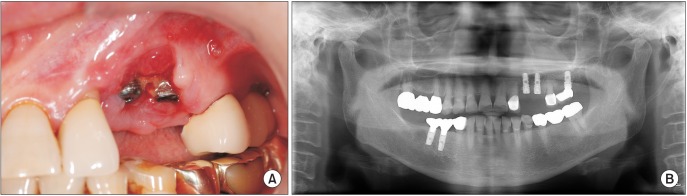

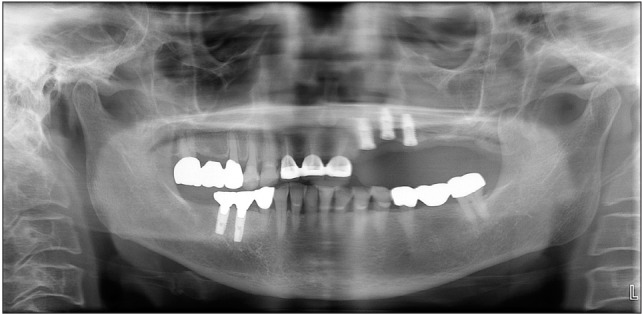

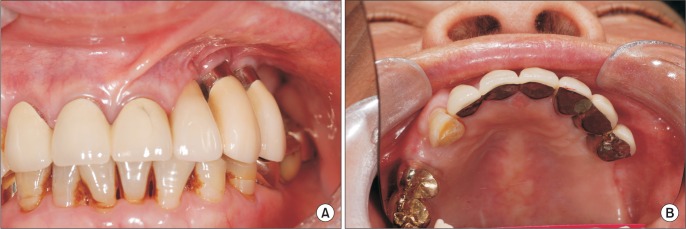

Upon physical and radiographic examination, the patient exhibited tenderness, gingival swelling, and redness on the buccal side of the two implants of the left upper canine and first premolar. Exposure of necrotic bone and alveolar bone resorption were observed at those sites.(Fig. 1)

The patient had been treated with surgical debridement therapy and antibiotic administration at a private clinic two months earlier in an attempt to relieve the symptoms. After the symptoms worsened, the patient was referred to our clinic. It was determined that the patient had been taking an oral bisphosphonate, 70 mg of alendronate (Fosamax; Merck, Whitehouse Station, NJ, USA) once per week for four years for the management of osteoporosis, but stopped the bisphosphonate therapy prior to her arrival at our clinic. In addition, the patient took medication for hypertension and coronary artery disease.

We prescribed antibiotics (amoxicillin with clavulanic acid and azithromycin), and the patient was instructed to maintain oral hygiene using chlorhexidine as a mouth rinse for two months, but the condition did not improve.

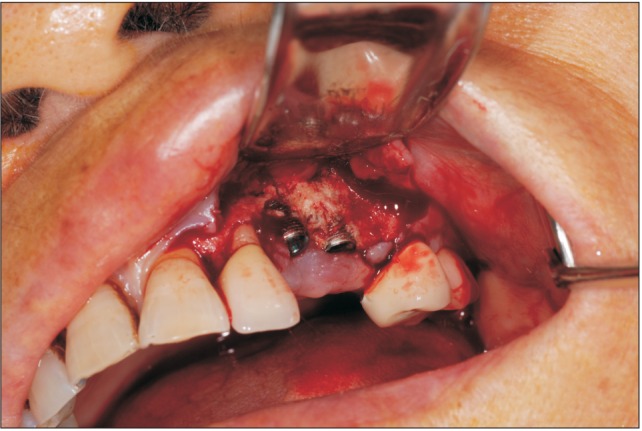

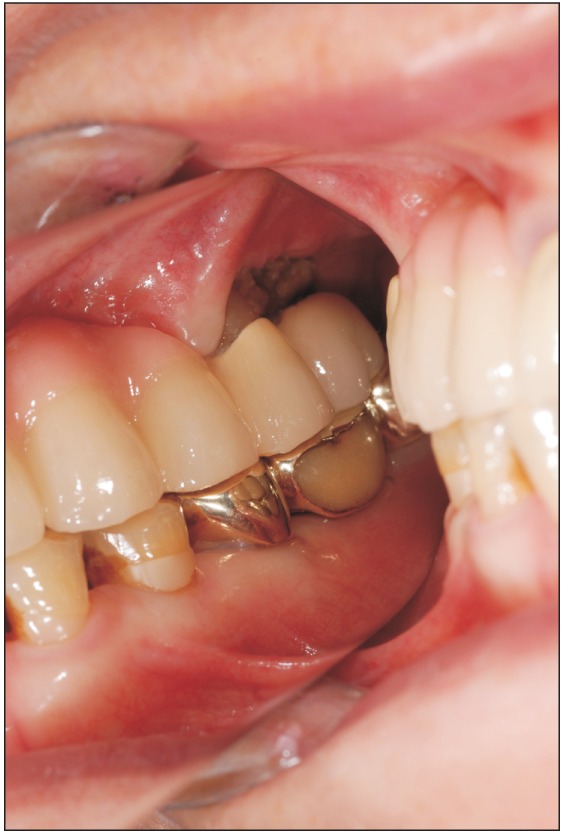

In May 2013, we diagnosed the patient with BRONJ and decided to remove the necrotic bone and implants. A sequestrectomy was performed at the left upper canine and first premolar area and the two implants were removed.(Fig. 2) After surgery, mucosal healing without any necrotic bone was achieved and a conventional fixed dental prosthesis was fabricated.(Fig. 3)

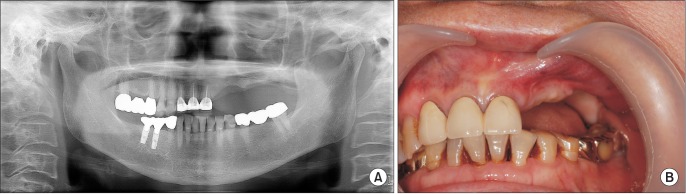

In August 2013, the patient complained of pain and gingival swelling in the left upper first molar region. The same initial treatment that was administered for the first episode was given here in terms of antibiotics and oral hygiene care, but necrotic bone around the first molar implant was eventually exposed.(Fig. 4)

In April 2014, the left upper first molar implant and the left upper second premolar tooth with necrotic bone were removed.(Fig. 5) After healing, the patient wore a removable partial denture, but after a period of time, she could not adapt to the removable prosthesis and strongly desired dental implants to restore her edentulous area again.

The patient was specifically informed about the risk of reoccurrence of BRONJ and was asked to sign a written document of informed consent. In October 2014, three implants (US II SA, 4×10 mm; Osstem, Seoul, Korea) were placed, replacing the left upper lateral incisor, canine, and first premolar.( Fig. 6) An oral prophylactic antibiotic (amoxicillin with clavulanic acid) was prescribed for seven days. The implant site was prepared with the standard protocol for submerged implants.

In March 2015, after an osseointegration phase of five months, the implants were exposed and healing abutments were placed. The implants exhibited excellent stability and the implant supported fixed prosthesis was fabricated. Eighteen months after implant surgery and thirteen months after restoration of the implants, the peri-implant region remained stable.(Fig. 7)

Generally, non-invasive procedures such as mucosa-supported removable dentures are recommended for dental prosthetic rehabilitation in patients with a history of BRONJ910. Unfortunately, removable dentures are often not tolerated in many patients, as seen in our presented case, and can also cause pressure spots or ulcers that might result in necrosis of the jaw. As a result, clinicians are tempted to consider implant supported prosthetic treatment as an alternative. The insertion of implants in patients who have successfully healed from BRONJ has been known to be highly risky and is not recommended8.

In this case, we decided to place dental implants in the same region of the jaw with a history of BRONJ for several reasons. First, healing after surgical debridement of BRONJ was uneventful, and excellent gingival and mucosal coverage was obtained. During surgical debridement, most of the alveolar bone, which has a higher turnover rate and may be more susceptible to the osteoclastic inhibition of bisphosphonate than the basal bone of the jaw, was removed411. We speculated that the basal bone of the jaw, which has a slower turnover rate, might be at less risk of recurrence than alveolar bone where BRONJ usually take place.

The patient had a history of taking oral bisphosphonates, the potency of which is usually lower than intravenously administrated bisphosphonates4. Following the appropriate surgical protocol, several promising results after implant therapy were reported in patients with a previous history of oral bisphosphonate therapy71213. Furthermore, the patient discontinued oral bisphosphonate therapy eighteen months before the re-implantation procedure.

Sound surgical principles of infection prevention and minimizing surgical invasiveness at the time of implant placement should be observed12348. The patient was prescribed a prophylactic antibiotic and was encouraged to maintain her oral hygiene. During implant surgery, the usage of new drill equipment, copious saline irrigation, and avoidance of excessive insertion torque of the implant were performed. The submerged technique of implant placement was chosen.

Patients who have already experienced BRONJ are considered to be at high risk of failure for the placement of dental implants. Therefore, implant treatment has been suggested up to this point from empirical, not scientific, evidence8. In our case, implant placement was successful in the same area with a history of healed BRONJ. There are very few similar reports published so far to our knowledge. This report indicates that implant placement could be possible after healing of BRONJ surgery in select cases. However, further long-term follow up and studies are necessary to confirm the viability of such a treatment.

References

1. Kushner GM, Alpert B. Osteomyelitis, osteoradionecrosis and BRONJ. In : Miloro M, Ghali GE, Larsen PE, Waite PD, editors. Peterson's principles of oral and maxillofacial surgery. 3rd ed. Shelton: People's medical publishing house;2012. p. 861–874.

2. Ruggiero SL, Dodson TB, Assael LA, Landesberg R, Marx RE, Mehrotra B. American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons position paper on bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws--2009 update. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009; 67(5 Suppl):2–12. PMID: 19371809.

3. Advisory Task Force on Bisphosphonate-Related Ostenonecrosis of the Jaws, American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons position paper on bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007; 65:369–376. PMID: 17307580.

4. Marx RE. Oral and intravenous bisphosphonate-induced osteonecrosis of the jaws: history, etiology, prevention, and treatment. 2nd ed. Chicago: Quintessence Publishing;2011.

5. Rasmusson L, Abtahi J. Bisphosphonate associated osteonecrosis of the jaw: an update on pathophysiology, risk factors, and treatment. Int J Dent. 2014; 2014:471035. PMID: 25254048.

6. Fliefel R, Tröltzsch M, Kühnisch J, Ehrenfeld M, Otto S. Treatment strategies and outcomes of bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (BRONJ) with characterization of patients: a systematic review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015; 44:568–585. PMID: 25726090.

7. Tallarico M, Canullo L, Xhanari E, Meloni SM. Dental implants treatment outcomes in patient under active therapy with alendronate: 3-year follow-up results of a multicenter prospective observational study. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2015; DOI: 10.1111/clr.12662. [Epub ahead of print].

8. Rugani P, Kirnbauer B, Acham S, Truschnegg A, Jakse N. Implant placement adjacent to successfully treated bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (BRONJ). J Oral Implantol. 2015; 41:377–381. PMID: 24593250.

9. Kwon TG, Lee CO, Park JW, Choi SY, Rijal G, Shin HI. Osteonecrosis associated with dental implants in patients undergoing bisphosphonate treatment. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2014; 25:632–640. PMID: 23278625.

10. Memon S, Weltman RL, Katancik JA. Oral bisphosphonates: early endosseous dental implant success and crestal bone changes. A retrospective study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2012; 27:1216–1222. PMID: 23057037.

11. Dixon RB, Tricker ND, Garetto LP. Bone turnover in elderly canine mandible and tibia. J Dent Res. 1997; 76:336.

12. Madrid C, Sanz M. What impact do systemically administrated bisphosphonates have on oral implant therapy? A systematic review. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2009; 20(Suppl 4):87–89. PMID: 19663954.

13. Ata-Ali J, Ata-Ali F, Peñarrocha-Oltra D, Galindo-Moreno P. What is the impact of bisphosphonate therapy upon dental implant survival? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2016; 27:e38–e46. PMID: 25406770.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download