II. Materials and Methods

We analyzed 1,824 fractures in 1,284 patients who were diagnosed with facial bone fractures and received closed reduction or open reduction and internal fixation at SMG-SNU Boramae Medical Center (Seoul, Korea) over 4 years, from January 2010 to December 2013. Fracture areas were limited to the midfacial area of the nasal bone, the orbital wall, zygomatic arch, maxillary wall, and lower facial area of the mandible. The upper facial area of the frontal bone, supraorbital wall, and cranium were excluded. This study was reviewed by the Institutional Review Board of SMG-SNU Boramae Medical Center (IRB No. 26-2015-106).

We evaluated the gender, age, and seasonal distribution for facial fractures; we then investigated the fracture area, cause of fracture in different ages and areas, time from injury to treatment, hospitalization periods, and post-operative complications. To study the seasonal distribution, the day of admission was used. In the analysis of fracture area, if a patient had multiple fractures, the number of fractures was counted. Maxillary fracture was limited to fracture of the maxillary wall. A zygomaticomaxillary complex (ZMC) fracture refers to simultaneous fracture in the ipsilateral orbital wall, the zygomatic arch, and the maxillary wall, which means ZMC fracture is not strictly an isolated fracture. Therefore, it should not be listed in the area category. However, the percentage of this type of fracture was relatively high, so we added a separate category for it to facilitate practical understanding. Using the IBM SPSS Statistics version 22.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA), we evaluated the statistical significance of seasonal incidence with ANOVA or the Kruskal-Wallis test. We also analyzed the left-right distribution of the fracture area with the Friedmann's test or the Wilcoxon signed rank test, and the correlation of cause with age and fracture area with the Pearson's chi-square test followed by multiple comparison using the Bonferroni method.

Go to :

IV. Discussion

In this study, patients with facial fractures who visited the emergency, dentistry, ophthalmology, otorhinolaryngology, and plastic surgery departments in SMG-SNU Boramae Hospital within the last 4 years were retrospectively analyzed based on the patients' medical records and radiological imaging. We attempted to update the most recent knowledge on facial fractures in the Seoul metropolitan region of Korea and to utilize the information as a guide for treatment and policy-making in the future without leaning on one perspective from a specific department.

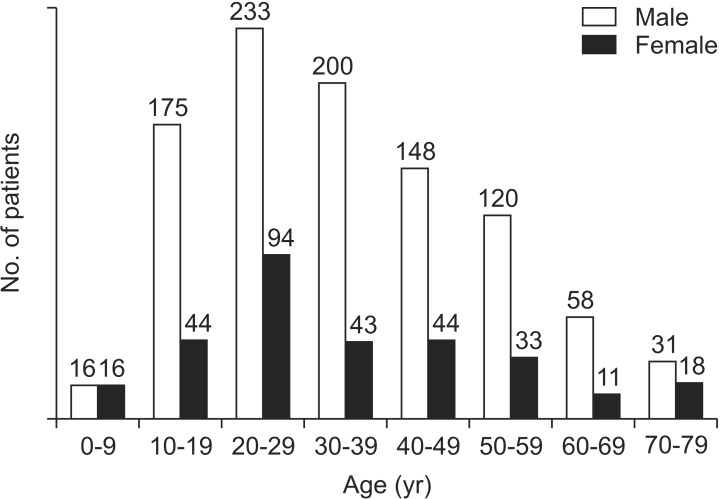

With the exception of pre-teens, men experienced the most fractures across all age groups. The average ratio of males to females was 3.2:1. This can be explained by the fact that men have more exposure to public behaviors such as drinking, driving, and assault than women. This finding is in accordance with other studies on fracture occurrence. Morris et al.

8 and Greathouse et al.

9 reported a 5:1 and a 2.7:1 ratio in their studies, respectively. In particular, Al Ahmed et al.

10 reported a huge bias against men with an 11:1 ratio, which may be due to ethnic characteristics in the UAE where social freedom for women is more restrictive than in other countries. On the other hand, in countries with more social freedom for women such as Greenland, Finland, and Austria, the sexual ratio remains 2.1:1

11.

Individuals in their 20s showed the highest incidence (25.5%) of fractures, and most patients were concentrated in the 10s to 40s (76.5%) age group. Likewise, Lee et al.

12 and Kim et al.

2 reported the highest occurrence in patients in their 20s. High physical and social activity in this age group may increase their chances of being exposed to trauma with a resultant high fracture incidence. On the other hand, there is also research that the rate of fractures in the elderly over 50 years old is increasing due to an aging society

11.

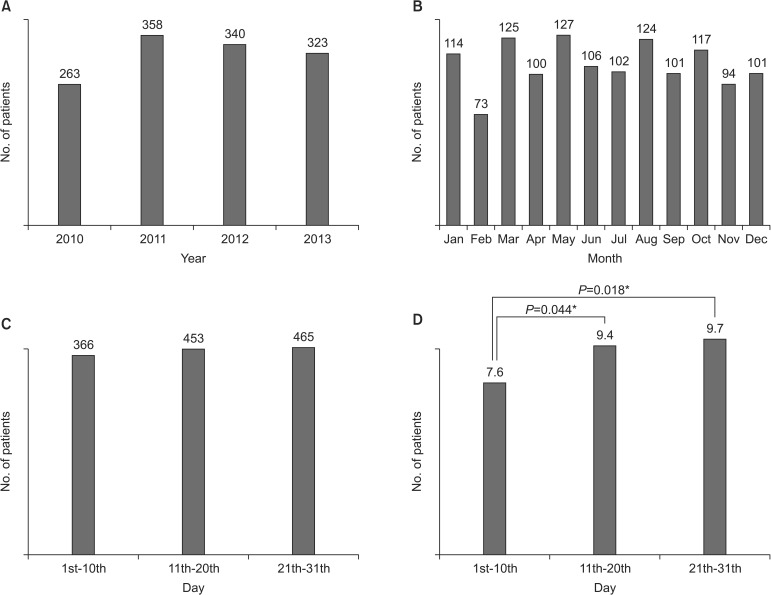

There was no significant difference in the number of patients over the 4 years studied from 2010 to 2013. In contrast, Jeon et al.

11 reported that the number of fractures approximately doubled each trimester in their analysis on facial trauma trends during 3 periods between 1981 and 2012. Kim et al.

2 reported an increase in the number of fractures over time. Additional study is necessary to determine whether this trend is due to an actual increase in the number of fracture patients or an increase in the diagnosis of fractures due to the availability of emergency facilities and increasing demand of attention by patients.

Fractures were most frequent in March, May, and August, but it was difficult to identify a trend. Lee et al.

12 reported that fractures occur in times of social activity or during vacations. Kwon et al.

13 reported fracture rates of 46.5% in June, July, and August, and 11.2% in December, January, and February, which implies that fractures occur in the hottest periods. When the month is divided into three periods, the middle and end of the month showed the highest incidence as social gatherings are more frequent during these periods. Though not addressed by this study, Sundays and the hours from 6 p.m. to midnight have been reported to be the most common times for accidents

1213.

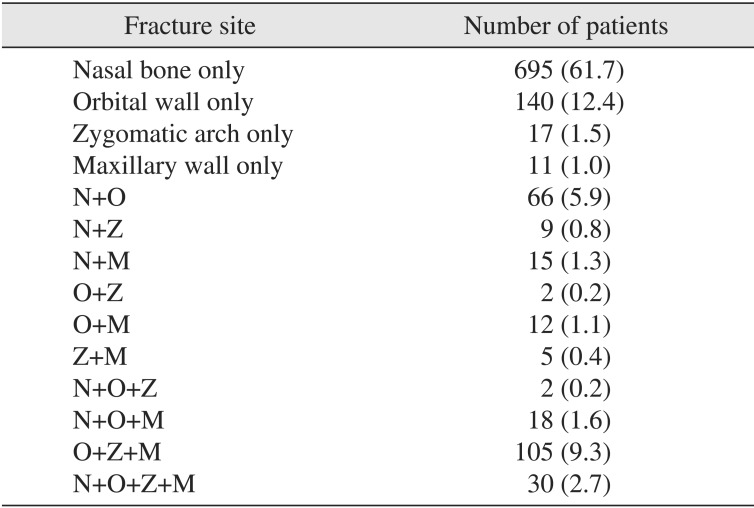

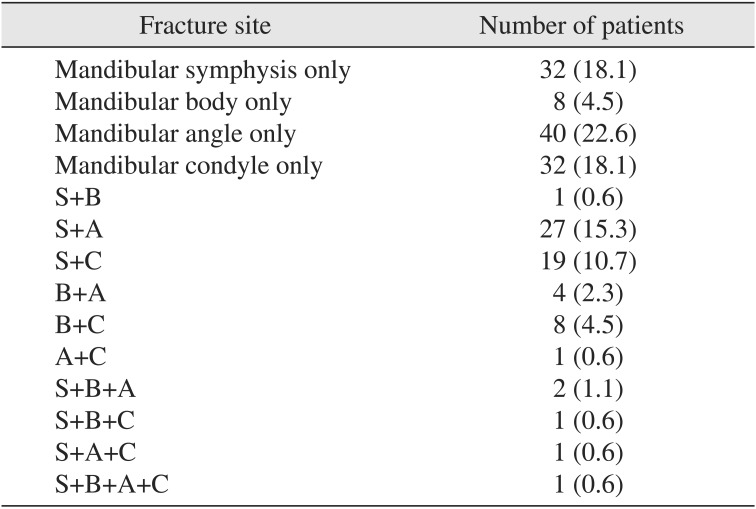

In 1970, Schultz

14 reported the incidence of fractures in different facial areas as follows: nasal bone (37.0%), zygoma and zygomatic arch (15.4%), mandible (10.9%), and maxilla (8.1%). In 1983, Brook and Wood

15 reported the order to be ZMC, mandible and maxilla, with midfacial fractures being more common than lower facial fractures. However, in 2006, Brasileiro and Passeri

16 reported facial fractures with the following incidence: mandible (41.3%), ZMC (38.9%), nasal bone (22.2%), maxilla (6%), with lower facial fractures occurring more frequently than midfacial fractures. In stark contrast, our study showed much more frequent fractures in the midface, with 86.2% in the midface, 12.2% in the mandible, and 1.6% simultaneously occurring in the midface and mandible. The nasal bone (65.0%) was the most frequent fracture area, followed by the orbital wall (29.2%), maxillary wall (15.3%), zygomatic arch (13.2%), ZMC (9.8%), and mandible (9.1%). In other words, fractures were more frequent in the nasal bone and orbital wall because the low mechanical strength and thinness increase the likelihood of a small force inducing fracture, compared to areas where greater impact must be applied to cause a fracture such as the ZMC or mandible. Furthermore, these results are in accordance with other research showing that nasal bone fractures are the most common, as the nose is the most exposed facial area

17. In mandible fractures, fracture in the symphysis was the most frequent (33.9% of mandible fractures), followed by the angle (30.6% of mandible fractures), condyle (25.4% of mandible fractures), and body (10.1% of mandible fractures). This is also quite different from the results of other studies. Iida et al.

18 reported the incidence of fractures as the condyle (33.6%), angle (21.7%), and symphysis (16.7%), while Morris et al.

8 and James et al.

19 reported that fractures were more common in the angle. In other words, all papers showed somewhat different results, which is attributed to social, economic, conventional, cultural, and regional differences. In addition, different distributions were observed in different clinical departments. That is, in studies performed in plastic surgery department, midfacial fractures were the most common whereas mandible fractures were the most common in studies conducted in dentistry departments

11.

Fractures on the left side are slightly more common than on the right. Excluding the nasal bone and symphysis areas (where it is difficult to distinguish left from right), out of 1,031 cases, 568 fractures occurred on the left side, 396 fractures on the right side, and 67 fractures occurred bilaterally. The incidence of fractures on the left side was 1.4 times higher. This is likely related to the fact that there are more right-handed than left-handed people. In the condyle, left side fracture was more frequent, but the difference was very small. The condyle also showed a higher ratio of bilateral fracture than other areas. This indicates that bilateral fracture should be considered when examining patients with condylar fractures.

Single site fracture was approximately 4.5 times higher than fractures in 2 or more areas. However, this figure might be exaggerated because 692 patients with single site fractures had nasal bone fractures, which was much higher than any other type of fracture. Therefore, excluding single site nasal bone fractures, the percentage of single site fractures was approximately 60.5%. Though fracture in only one area was still more frequent, 2 out of 5 patients were injured in two or more areas. Furthermore, after excluding the ZMC area, which had the highest single site fracture incidence after the nasal bone, the percentage of single site fractures was approximately 50%, which indicates that 1 out of 2 patients had injuries in 2 or more areas. In fact, ZMC fracture is a multiple fracture occurring in four areas. If we take this into account, it is expected that multiple fractures in 2 or more areas is more frequent than single site fractures other than nasal bone fractures. That is, because the face has bones clustered in a relatively small area, multiple fractures are likely to occur frequently. This implies that consideration of multiple areas is often necessary in treating facial bone fractures.

Many previous studies on the cause of fractures, including the study by Morris et al.

8, van Beek and Merkx

20, Ugboko et al.

21, Lee et al.

12, reported traffic accidents as the most common cause. Other studies reported assault as the major cause of facial bone fractures

1522. There is also a report indicating that the major cause of fractures has changed from traffic accidents to falls

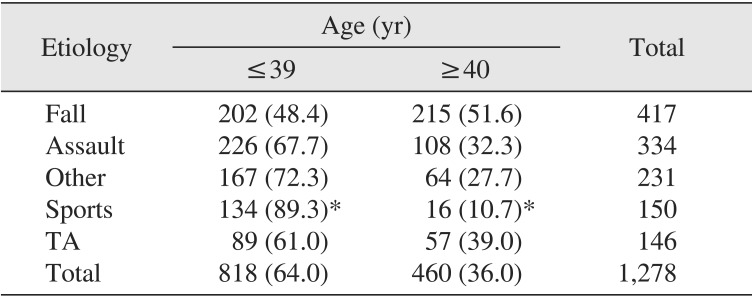

11. In this study, a fall was the most common cause of fracture at 32.5%, followed by assault. Therefore, 1 out of 2 patients in this study were injured due to a fall or assault. Injury due to traffic accidents was comparatively uncommon (11.4%). This is likely related to our hospital's setup as we do not specialize in traffic accidents. Assault was the most common cause in individuals in their 30s and younger, whereas in those 60 years and over, a fall was the most common cause. Kwon et al.

13 also reported that assault was the main cause of facial bone fracture in young adults and middle-aged adults, while falls or traffic accidents were the main causes in the eldery. In addition, patients under 39 years had relatively more injuries related to sports than patients over 40 years in our study. It is the natural outcome associated with the relative inactivity of the elderly. All these results imply that behaviors related to each age group affect the cause of fracture. Jeon et al.

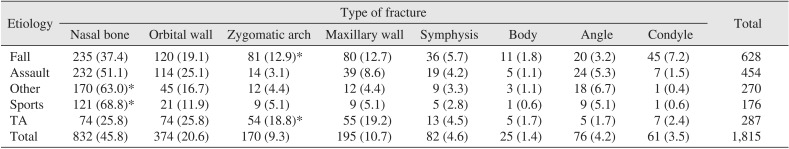

11 argued that insurance coverage must be carefully considered when analyzing the cause of bone fractures. This suggests that since insurance does not cover assault in Korea, it should be taken into account that patients may list other causes such as falls and so on as the primary cause of injury. A third of patients who had fractures due to assault or falls were found to be intoxicated at the time of injury, which suggests a connection between facial bone fracture and alcohol consumption. Although there have been few studies regarding the correlation of cause and site of injury, specific causes may appear to be focused in different areas. In this study, once injuries related to other causes or sports occurred, they resulted in nasal bone fracture more easily. The same applied to zygomatic arch fractures due to fall or traffic accident.

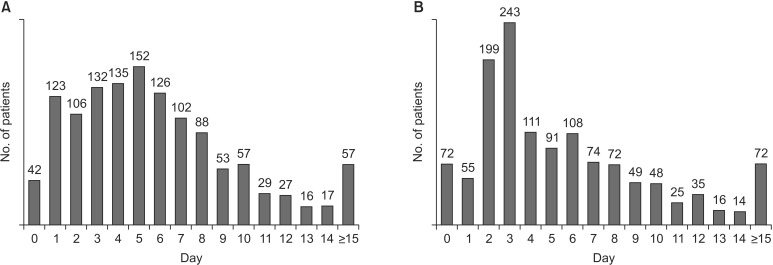

During the secondary healing process after bone fracture, a hard callus starts to form after approximately 3 weeks

23. Therefore, it is optimal to treat or perform surgery within 2 weeks after the injury for adequate reduction without intentional osteotomy. Also, when nerves or muscles are injured or pressured by fracture fragments, it is preferable to treat the injury as soon as possible

13. The average time between injury and treatment was 6 days in this study. Three out of 4 patients received the necessary treatment within 1 week and 95% received the necessary treatment within 2 weeks, showing that treatment was performed within the appropriate time period. In previous studies, treatment was performed within 2 weeks

12. Meanwhile, in cases postponed over 15 days, nasal bone fracture and orbital wall fracture were most common, accounting for 28 cases (49.1%) and 21 cases (36.8%), respectively. The most common cause of delay was non-medical reasons, such as late presentation to the hospital due to few symptoms after injury or postponement of surgery by the patient for personal reasons, accounting for 28 cases (49.1%). The second most common cause was a late decision regarding the necessity of treatment due to detection of changes in the nasal tip or abrupt diplopia during the follow-up period, occurring in 17 cases (29.8%). That is, the decision to perform surgery following nasal bone or orbital wall fractures with no serious symptoms occasionally takes some time. Additionally, there were cases in which treatment was postponed due to systemic problems (10 cases) or where primary organ surgery was first performed due to multiple traumas in addition to facial bone fractures (2 cases).

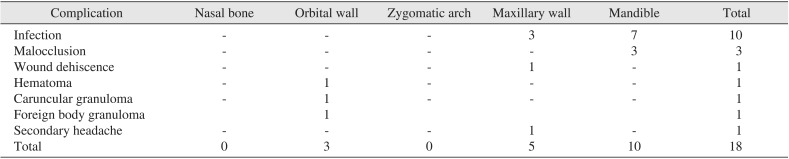

The incidence of complications after facial bone fracture surgery is reported to vary from 8% to 11%. Complications include infection; malocclusion; malunion; exposure of the metal plate; decreased sensation; scar formation; and ophthalmologic complications such as diplopia, enophthalmosis, ectropion, limitation of extraocular muscle action, and loss or decrease in vision. Some studies reported that ophthalmologic complications account for almost half of all complications

1213. The causes of complications are unskilled practitioners or drinking and smoking by patients

2425. In this study, the occurrence of complications was very small, with a total of 17 patients (0.013%). This seems to be due to the fact that almost all surgeries were performed by a specialist with proper clinical experience. The most common complications were postoperative infection and malocclusion as in other studies; these were most frequently found in the mandible. As patients with an injury to treatment interval of over 3 weeks did not show any complications, the relationship between postponement of treatment and occurrence of complications could not be established. This also requires further study.

Since preceding studies mostly analyzed facial bone fractures in patients that visited specific departments, the occurrence of injuries was focused on a particular area, which caused difficulties in the objective analysis of facial bone fractures

11. However, this study focused on all facial fracture patients who visited our hospital regardless of the department, which enables a more precise analysis. However, as it uses data from only one hospital, the generalizability may be reduced. Therefore, further epidemiological studies that integrate all data from nearby hospitals are required.

Go to :

V. Conclusion

The results of this study on facial bone fractures are summarized as follows.

1. Fractures occurred approximately 3.2 times more often in men, and 76.4% of the patients were within the 10s to 40s age group.

2. Fractures were more prevalent in the middle and end of a month than the beginning.

3. Midfacial fractures were 6.4 times more frequent than mandible fractures. When counting multiple fractures separately, the order of incidence was the nasal bone (65.0%), orbital wall (29.2%), maxillary wall (15.3%), zygomatic arch (13.2%), ZMC (9.8%), symphysis (6.5%), angle (5.9%), condyle (4.9%), and body (1.9%).

4. Fractures occurred 1.5 times more often on the left side than on the right.

5. Single site fractures were 4.5 times more common, but this figure includes single site nasal bone fractures. When nasal bone fractures are excluded, more than half of the patients had multiple fractures in 2 or more areas.

6. The main causes of fractures were a fall (32.5%) and assault (26.0%), and one third of these fractures were related to alcohol use.

7. Patients injured by other causes or sports had a high probability of nasal bone fracture. Falls and traffic accident were likely to cause zygomatic arch fractures.

8. Seven out of 10 patients received necessary treatment within a week and 95.5% were discharged within 2 weeks of treatment.

9. The incidence of complications was very low (0.013%). Postoperative infection and malocclusion were the most common complications, and they occurred more frequently in mandible fractures.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download