Abstract

Sinonasal sarcoidosis in the head and neck region is infrequent. Its occurrence can be either isolated in combination with other systems. The literature reveals that the occurrence of sinonasal sarcoidosis without lung involvement is rare. In general, sarcoidosis is a chronic non-caseating granulomatous disease of unknown origin, often identified after biopsy. In this article, we report on a benign tumor of the face that produced a diagnostic dilemma, necessitating refinement of the surgical access and in toto removal of the benign tumor.

Sinonasal sarcoidosis (SNS) is a rare condition that was first described by Boeck in 19051. Occurrence is either isolated or part of a multisystem2. In general, sarcoidosis is a chronic non-caseating granulomatous disease of unknown origin. It is usually associated with a lung lesion, and occurrence without lung involvement is very rare3. Sarcoidosis is characterized by a non-caseating granuloma found during biopsy. The alleged prevalence rate varies from 0.7% to 10%4, and appears to occur in individuals living in a moist habitat.

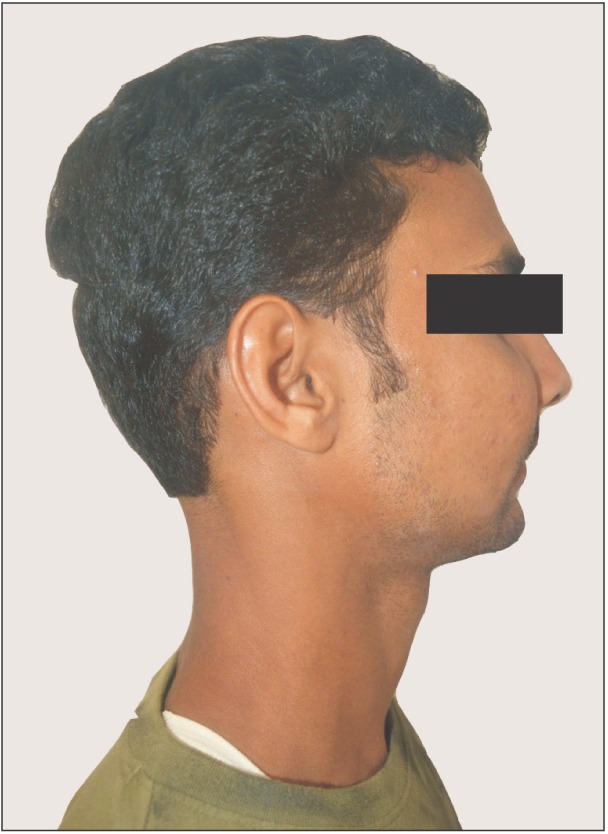

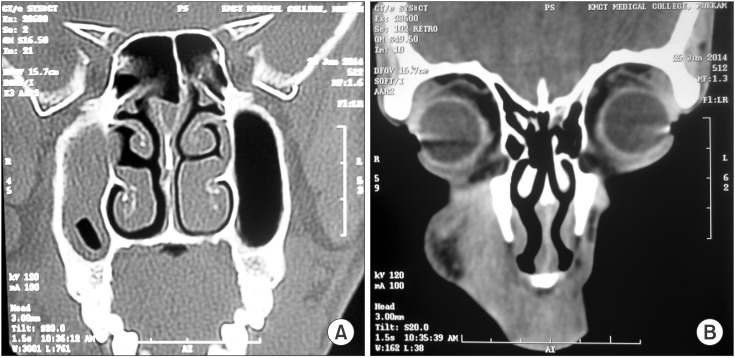

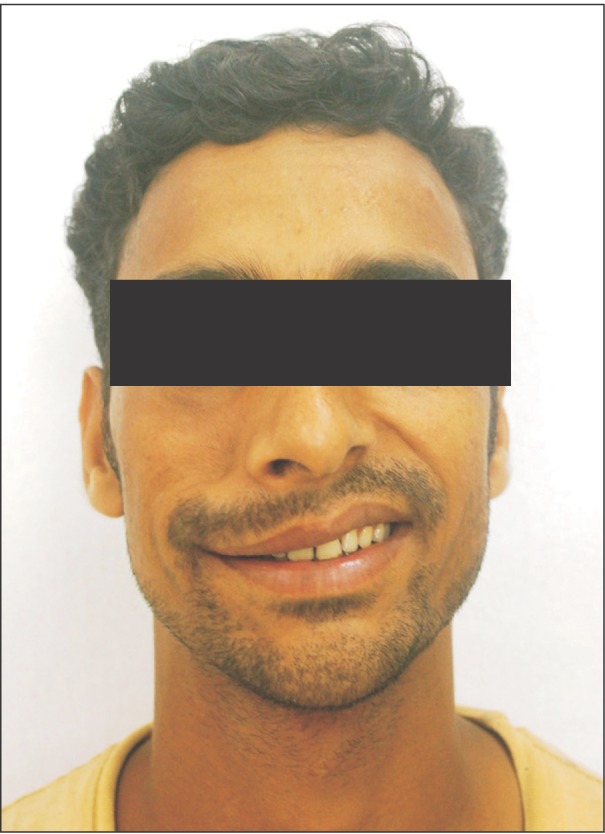

A 27-year-old male patient reported to the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, outpatient department of Kunhitharuvai Memorial Charitable Trust Dental College and Hospitals with the chief complaint of swelling in the upper right face region for the previous six months.(Fig. 1) History revealed altered sensation on the right mid-face region for six months, noticed during his daily chores. No history of pain was present. The swelling was present for 4 months, first noticed as a small hardness that progressively developed into the current size. Swelling was diffuse in nature and was only noticeable on close examination. Intraoral examination revealed no specific findings. There was no tooth mobility, or tenderness on gingiva. There was no presence of any carious tooth or tenderness on percussion. All periodontal health parameters were within normal limits. There was no previous history of any sarcoidosis. On inspection, the swelling was ovoid in shape, and on palpation, a soft-swelling, non-tender, smooth tumor with well-defined borders was found. Computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a well-defined dense soft tissue tumor with homogenous enhancement extending from the right infra orbital foramen to the buccal vestibule along with sinus involvement.(Fig. 2) Chest X-ray revealed no lesions with cross specialty consultations. The case was provisionally diagnosed as a granulomatous tumor after incisional biopsy and was posted for excision in toto, using blunt dissection with vestibular incision for the superficial lesion and the Caldwell-Luc approach for the sinus lesion, under general anesthesia.

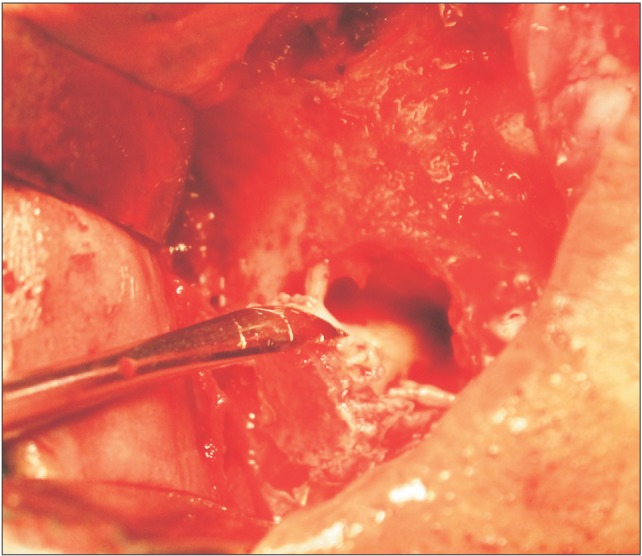

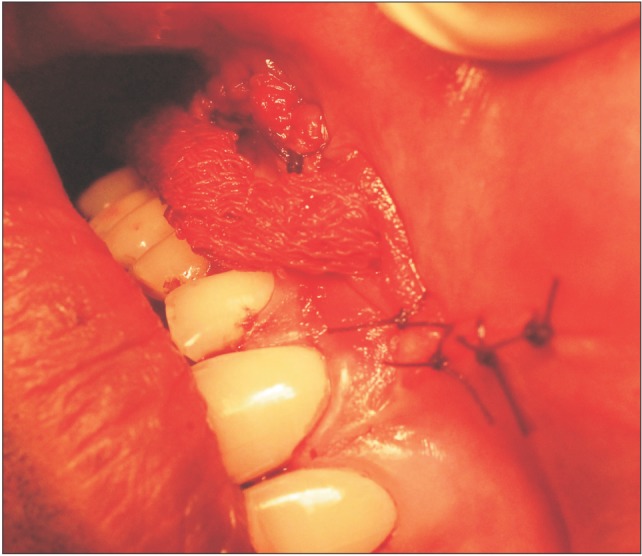

A vestibular incision was made extending from the right central incisor region to the right molar region.(Fig. 3) The tumor mass was encapsulated (5×3 cm), and the dissection proceeded with the aim of in toto removal of the lesion.(Fig. 4) During removal of the superficial lesion, an attachment of the mass to the infraorbital nerve (ION) with minimal erosion of the infraorbital foramen was found, which was not previously appreciated in the CT scan. A modified Caldwell Luc procedure was performed by creating a window inferior and involving the foramen in order to further access the lesion.(Fig. 5) The whole nerve and lesion was excised in toto. Involvement of the ION suggested a possible inclusion of the terminal branches of the facial nerve as well. Incisions were closed primarily after antral pack placement.(Fig. 6) The specimen was sent for histopathological studies. Final diagnosis of SNS was made upon clinical, radiographical and histopathological studies.

The postoperative recovery period was uneventful and supportive glucocorticoid therapy was later given. One-month recall showed paresthesia over the right buccal, lateral nasal, superior labial, infraorbital regions and diminished motor function over the right maxillary region along with diminution of the nasolabial fold.(Fig. 7) At the one-month review, the patient was referred to another center for further investigation to rule out any other organ involvement with sarcoidosis.

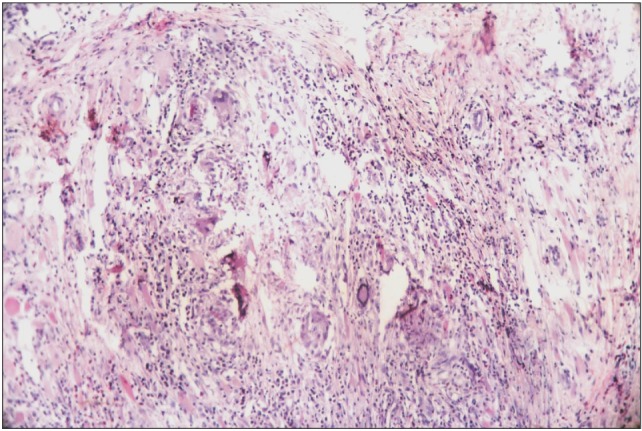

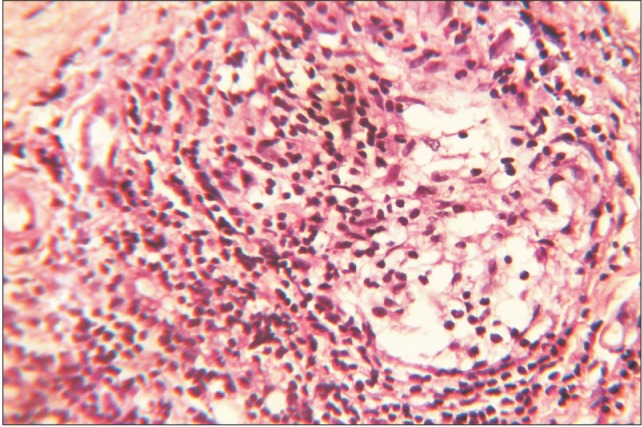

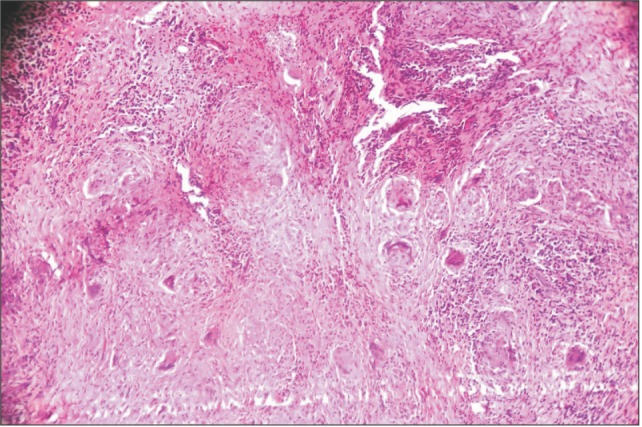

Sarcoidosis is a classic epithelioid granuloma producing disease. The most significant difference between sarcoidosis and tuberculosis is that sarcoidosis lacks caseous necrosis and acid fast organisms. Formation of compact granulomas consists of epithelioid cells with scattered multinucleated giant cells, usually of the Langhans type. Peripheral lymphocytes, plasma cells, and fibroblasts are usually present, and there may be formation of dense collagen. Within the granulomas, inclusion bodies may be seen.(Fig. 8, 9, 10)

The required permissions have already been obtained from the patient and can be submitted on request.

Isolated SNS is a rare entity that clinically presents with signs of chronic inflammatory rhinitis and responds poorly to conventional treatment1. Complete ear, nose and throat (ENT) examination and guided biopsy is required for diagnostic confirmation5. Differential diagnosis includes Wegener granulomatosis, Churg-Strauss syndrome, aspergillosis, rare ENT localizations of Crohn's disease and actinomycosis6. Most frequent sites include the nasal septum and inferior turbinates, followed by paranasal sinuses, nasal bone and cartilage and sub-cutaneous tissues in that region2.

Diagnosis of sarcoidosis requires consideration of all clinical and pathological features. The etiology of sarcoidosis is still unknown, so diagnosis can never be made with 100% certainty. Patients are evaluated for sarcoidosis in two scenarios. In the first scenario, the patient may undergo biopsy of the asymptomatic tumor to reveal a non-caseating granuloma. And if the features are consistent with granuloma and there are no other alternative causes for non-caseating granuloma, the patient can be diagnosed with granuloma. This was the scenario in this case study. The second scenario is a patient presenting with signs or symptoms suggesting sarcoidosis, such as the presence of bilateral adenopathy in an otherwise asymptomatic patient or a patient with uveitis or a rash consistent with sarcoidosis. At this point, a diagnostic procedure should be performed and the presence of sarcoidosis should be confirmed. The Kviem-Siltzbach procedure is a specific diagnostic test for sarcoidosis in which specially prepared tissue derived from the spleen of a known sarcoidosis patient is intradermally injected, and the injected site is biopsied 4 to 6 weeks later. If non-caseating granulomas are seen, this is highly specific for the diagnosis of sarcoidosis. The diagnosis of sarcoidosis can never be certain, and over time, other features may arise that lead to an alternative diagnosis. Evidence for new organ involvement may eventually occur, confirming the diagnosis of sarcoidosis7.

Krespi et al.8 proposed local treatment as the mainstay treatment. Endoscopic sinus surgery is the preferred modality of surgical treatment to alleviate chronic local symptoms9. The literature describes CT findings of mucosal thickening, sinus opacification and signs of chronic sinus inflammation like destruction, erosions or bone lesions1. Treatment of SNS includes topical or systemic steroids and sinonasal surgery. Response to treatment varies from complete remission to no improvement at all. Repeated sinus surgeries, despite systemic and topical steroid treatment, have been reported in the literature, implying that SNS is a rather serious variant of sarcoidosis. Another complication is the high relapse rate in spite of the long-term therapy10. In this case there was neural involvement, which is a rare complication of SNS11.

SNS should be included in the differential diagnosis for swelling occurring in the maxillofacial region, despite its rare occurrence. A more skeptical diagnostic approach is recommended to survey the extent of nerve involvement and possible intracranial extension. In toto surgical removal followed by supportive glucocorticoid therapy and follow up should be considered. More future perspective studies are suggested to assess the benefits of initial surgery and supportive glucocorticoid therapy for isolated SNS.

References

1. Scadding JG. Sarcoidosis. London: Eyre & Spottiswoode;1967.

2. Braun JJ, Gentine A, Pauli G. Sinonasal sarcoidosis: review and report of fifteen cases. Laryngoscope. 2004; 114:1960–1963. PMID: 15510022.

3. Dessouky OY. Isolated sinonasal sarcoidosis with intracranial extension: case report. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2008; 28:306–308. PMID: 19205596.

4. Mallis A, Mastronikolis NS, Koumoundourou D, Stathas T, Papadas TA. Sinonasal sarcoidosis: a case report. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2010; 14:1097–1099. PMID: 21375142.

5. deShazo RD, O'Brien MM, Justice WK, Pitcock J. Diagnostic criteria for sarcoidosis of the sinuses. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999; 103:789–795. PMID: 10329811.

6. Neville E, Mills RG, Jash DK, Mackinnon DM, Carstairs LS, James DG. Sarcoidosis of the upper respiratory tract and its association with lupus pernio. Thorax. 1976; 31:660–664. PMID: 1013937.

7. Crystal RG. Sarcoidosis. In : Wonsiewicz M, Englis MR, editors. Harrison's principles of internal medicine. 16th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill;2005. p. 2022–2023.

8. Krespi YP, Kuriloff DB, Aner M. Sarcoidosis of the sinonasal tract: a new staging system. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995; 112:221–227. PMID: 7838542.

9. Long CM, Smith TL, Loehrl TA, Komorowski RA, Toohill RJ. Sinonasal disease in patients with sarcoidosis. Am J Rhinol. 2001; 15:211–215. PMID: 11453511.

10. Kirsten AM, Watz H, Kirsten D. Sarcoidosis with involvement of the paranasal sinuses: a retrospective analysis of 12 biopsy-proven cases. BMC Pulm Med. 2013; 13:59. PMID: 24070015.

11. Mazziotti S, Gaeta M, Blandino A, Vinci S, Pandolfo I. Perineural spread in a case of sinonasal sarcoidosis: case report. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2001; 22:1207–1208. PMID: 11415921.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download