Abstract

Osteomyelitis is classified into three groups according to its origin: osteomyelitis that originates from the blood supply, osteomyelitis related to bone disease or vascular disease, and osteomyelitis related to a local infection of dental or non-dental origin. The present case involved osteomyelitis related to a local infection of dental origin and was located in the rear area of the lingula of the mandible. We decided to use sagittal split ramus osteotomy to access the osteomyelitis area. Under general anesthesia, we successfully performed surgical sequestrectomy and curettage via sagittal split ramus osteotomy.

Go to :

Osteomyelitis refers to inflammation of the bone marrow and clinically describes a bone infection that originates in the marrow space and sponge bone and expands to the periosteum. With progression of the inflammation, a sequestrum is formed by necrosis of a piece of sponge bone: the inflammation expands to the Haversian canal and Volkmann's canal, ischemia occurs in the cortical bone, pus forms, the periosteum is separated from the bone, and necrotic cortical bone is separated from the surrounding bone and becomes a sequestrum. Osteomyelitis is classified into three groups according to origin: osteomyelitis that originates from the blood supply, osteomyelitis related to bone disease or vascular disease, and osteomyelitis related to a local infection of dental or non-dental origin1. The present case involved osteomyelitis related to a local infection of dental origin and was located in the rear area of the lingula of the mandible. Under general anesthesia, we successfully performed surgical sequestrectomy and curettage via sagittal split ramus osteotomy (SSRO).

Go to :

A 71-year-old male patient visited the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery at Busan Paik Hospital (Busan, Korea). His chief complaint was swelling on his left buccal and submandibular area. He had been feeling pain in that area for four to five days. He visited our hospital because of severe swelling that began the day prior. He also had hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and cerebral infarction, for which he had been treated in a local medical clinic for three years. Upon clinical examination, swelling, tenderness, and pain were observed in the left buccal and submandibular area. Moreover, percussions of the maxillary left first molar (#26) and the mandibular left second molar (#37) were observed, and the mandibular left second molar (#37) had severe mobility. Pus discharge was observed through the gingival sulcus of those teeth.

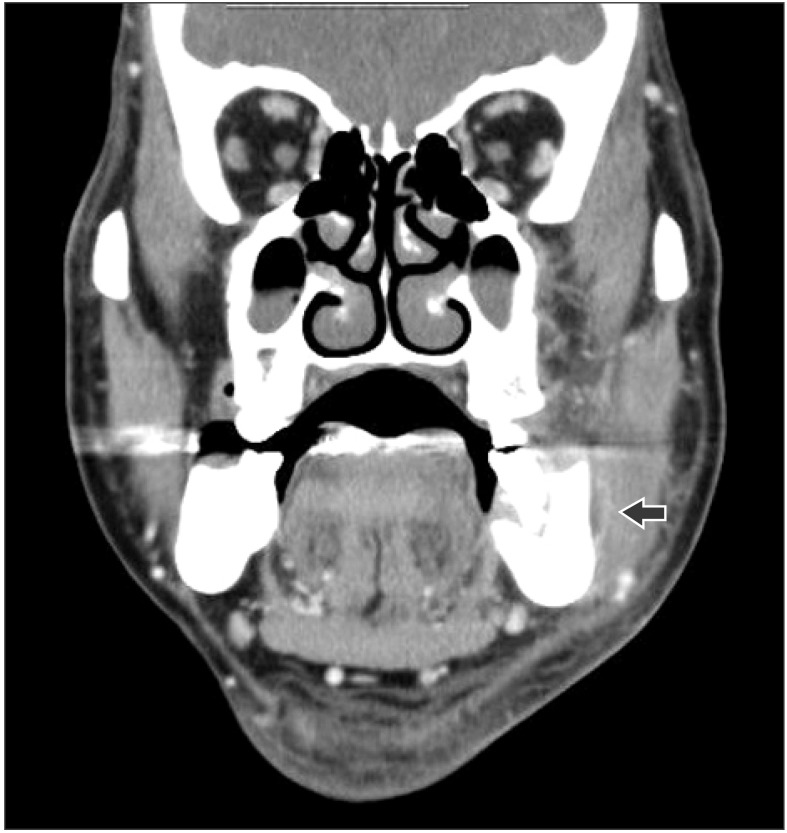

Clinicopathological examination during the initial visit resulted in a whole blood cell (WBC) count of 14.16×103/mm3 and a C-reactive protein (CRP) level of 8.31. Panorama radiography revealed severe alveolar bone loss around the mandibular left second molar (#37) and multiple retained roots, and dental caries in the mandibular right first molar (#46).(Fig. 1) Computed tomography (CT) revealed an abscess with pus formation in the left buccal and submasseteric spaces.(Fig. 2)

From clinical and radiographic examinations, a left buccal abscess in the left mandibular second molar was diagnosed. Under local anesthesia, incision, drainage, and extraction of the left mandibular second molar were performed, followed by bacterial culture of the discharged pus. After admission, he was administered cephalosporin, aminoglycoside, and metronidazole. The symptoms improved through appropriate drainage and antibiotic treatment. After four days in the hospital, the patient was discharged.

During a follow-up visit at the outpatient department, the patient complained of pain whenever he opened his mouth. A decrease in the size of the mouth opening was observed, indication mouth opening limitation. About 10 days after the patient was discharged, mouth opening limitation continued, and swelling of his left buccal and parotid areas was observed. Neck CT was performed, which showed recurrence of the previous abscess in the left buccal and submasseteric space, in addition to a new abscess in the left pterygomandibular and parapharyngeal space (2.5×5.1 cm).(Fig. 3) Clinicopathological examination revealed a WBC of 16.07×103/mm3 and a CRP level of 13.42. Pain, chilling, and local heat were observed. The patient was hospitalized again.

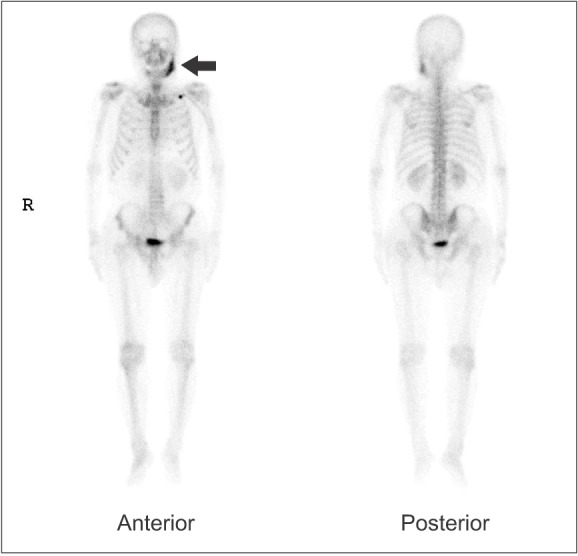

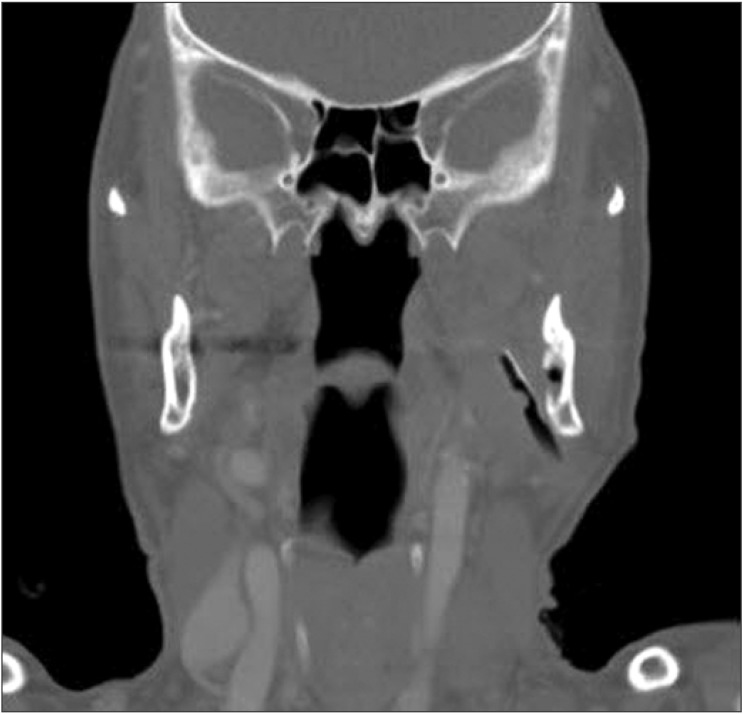

Extraoral incision and drainage through a left submandibular approach was performed upon insertion of a 6-mm penrose drain under local anesthesia on the admission day. On the seventh day after operation, the CRP level decreased to 1.24. After two days, the CRP level was 0.63 (almost normal), but pus discharge through the drain continued. Fourteen days after operation, the CRP level normalized to 0.16, but pus discharge through the drain continued. Follow-up neck CT and bone scan were performed. In the bone scan, enhancement of the left mandible increased and probable osteomyelitis in the left mandible was diagnosed.(Fig. 4) Neck CT showed a sequestrum and osteomyelitis in the rear area of the lingula of the left mandible.(Fig. 5)

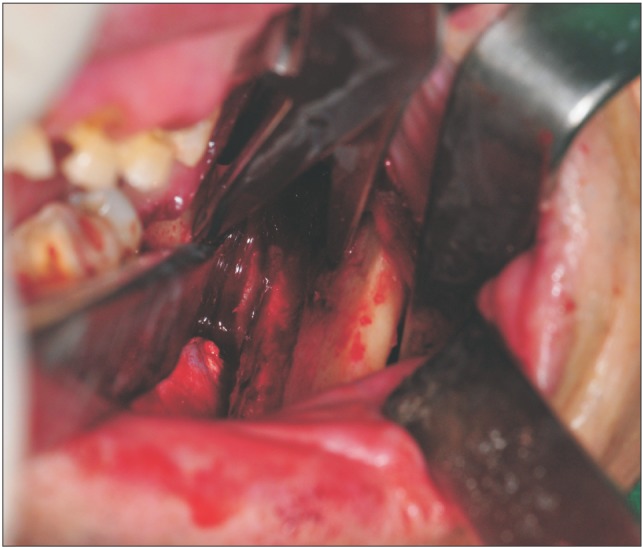

Because osteomyelitis remained, pus discharge continued, and surgical sequestrectomy and curettage were required. Among the surgical approaches available in this case, an intraoral approach was difficult due to the location of the inferior alveolar nerve, and an extraoral approach faced challenges regarding the introduction of bone reduction burs and instruments. Therefore, a SSRO was used to approach the osteomyelitis area. Under general anesthesia, we successfully performed surgical sequestrectomy and curettage via SSRO. (Fig. 6) The rear area of the lingula of the mandible was accessed easily via SSRO, and the operation was successful. (Fig. 7) Then, rigid fixation was performed with a plate, screws, and wire. Intermaxillary fixation was performed with an arch bar; the fixation duration was five days. After surgical sequestrectomy and curettage, symptoms improved and pus discharge ceased. Twelve days after the operation, the patient was discharged. After about six months, plate removal was performed under local anesthesia and the clinical results were good.

Go to :

Osteomyelitis can occur through local infection of dental caries, periodontal disease, infection of nearby soft tissue, sinusitis, ear infection, or infection of a fracture site. The present case was osteomyelitis related to a local infection of dental origin. Kang et al.2 reported osteomyelitis in the zygoma caused by odontogenic maxillary sinusitis. The origin tooth was the right first molar. Under general anesthesia, osteomyelitis of the zygoma was treated via sequestrectomy and surgical curettage, and the maxillary sinusitis was treated through a Caldwell-Luc operation. Kim et al.3 reported the treatment of osteomyelitis caused by mandible fracture. In the patient, an untreated fracture of the left mandibular angle progressed to osteomyelitis. The patient was treated surgically and through rigid fixation with closed tube irrigation, and the clinical results were good. Heo et al.4 reported the treatment of osteomyelitis after open reduction of a mandibular fracture. After open reduction of the mandibular fracture, osteomyelitis and non-union occurred in the patient. The patient was treated via mandibular osteotomy, sequestrectomy, iliac bone graft, and hyperbaric oxygen therapy, and the clinical results were positive. In this way, osteomyelitis can occur through local infection due to periodontal disease, sinusitis, or infection of the fracture site.

According to a recent microbiological study, the bacterial origins of osteomyelitis are similar to dental infection: Streptococcus, anaerobic bacteria like Peptostreptococcus, Gramnegative bacillus like fusobacterium, and bacteroides1. In the present case, the origin of the osteomyelitis was chronic apical periodontitis of the left second molar. With progression of the disease, an abscess in the left buccal and sub-masseteric space occurred. The abscess occurred in the left pterygomandibular space and the parapharyngeal space, along with osteomyelitis in the rear area of the lingula of the mandible. The origin bacterium was alpha-hemolytic Streptococcus.

In a recent study, osteomyelitis occurred mainly on the mandibular body (83%), followed by the mandibular symphysis area (20%), the angle area (18%), the ramus (18%), the condyle (2%), and the maxilla (1%). The location of osteomyelitis in the present case was the rear area of the lingula of the mandible.

Radiography, CT, and bone scan can be used to diagnose osteomyelitis. In the early stage, bony change can be observed after as little as one to two weeks using radiographic film and CT. Because bony change can be detected when bony demineralization of 30% to 50% occurs and it takes about one to two weeks. A bone scan using radioactive isotopes helps with early detection of osteomyelitis and can yield a positive response after 24 hours.

Osteomyelitis treatment requires both medical and surgical methods. Because many osteomyelitis patients have a weak body defense mechanism, medical consultation will sometimes be needed. First, patients with acute osteomyelitis must be given appropriate antibiotics. In cases of osteomyelitis that originate from dental infection or fracture of the jaws, the originating conditions will be treated simultaneously. In most cases, because the causative bacteria of osteomyelitis are Streptococcus, the first antibiotic choice is penicillin. Surgical treatments of acute suppurative osteomyelitis are extraction of non-vital teeth in the infection site, placement of wire and a bone plate for internal fixation, and restrictive removal of the sequestrum with mobility1.

Treatments for chronic osteomyelitis require active medication with antibiotics and surgical treatment. Patients need in-hospital care and intravenous injection of antibiotics to control their initial symptoms because of severe obstruction of the blood supply in the osteomyelitis site. The first choice of antibiotics is penicillin. At the time of surgical treatment, bacterial culture and antibiotic sensitivity test are needed. According to the results of these tests, the antibiotics administered may be changed. Surgical treatment must be carried out aggressively in the ischemic and necrotic area. Commonly used surgical treatments are sequestrectomy and saucerization.

The approach methods in these surgical treatments are intraoral and extraoral. Simple cases can be treated with an intraoral approach. However, complicated or extensive cases can be treated using an extraoral approach or a combined intraoral and extraoral approach. Kim et al.3 reported treatment of osteomyelitis caused by fracture of the mandible through complete removal of the inflamed tissue, rigid fixation with mini-plates, and closed catheter irrigation using an extraoral approach. Lee et al.5 reported conservative treatment of chronic suppurative osteomyelitis on the mandibular body to the condyle area. They used surgical exploration and sequestrectomy with an extraoral approach. Kang et al.2 reported osteomyelitis in the zygoma caused by odontogenic maxillary sinusitis. They used a Weber Ferguson incision with sub-cilliary extension for surgical treatment. An extraoral approach can be used commonly in complicated or extensive cases.

In our case, however, we used an intraoral approach for surgical treatment, because the osteomyelitis location was at the rear area of the lingula of the mandible. This area was challenging, because of the difficulty of approach. In the extraoral approach, both visualization of the surgical site and introduction of surgical instruments and burs are very difficult. Therefore, we used an intraoral approach via SSRO. Through this approach, we were able to visualize the surgical site and it provided sufficient access for the necessary surgical instruments. The surgical treatments were successful.

In conclusion, we reported a patient with osteomyelitis that had advanced to the rear area of the lingula of the mandible. The patient was treated via SSRO to access the surgical site, which provided good visualization, and thereby allowed appropriate saucerization and surgical curettage. Good clinical results were realized. We suggest that osteotomy is sometimes useful for the treatment of osteomyelitis in sites that are difficult to access.

Go to :

References

1. Korean Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. Textbook of oral and maxillofacial surgery. 1st ed. Seoul: Dental and Medical Publishing Co.;1998.

2. Kang HJ, Lee JH, Kim YD, Byun JH, Shin SH, Kim UK, et al. Osteomyelitis occuring in the zygoma caused by odontogenic maxillary sinusitis: case report. J Korean Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004; 30:251–254.

3. Kim SK, Sohn DS, Go MS, Seo JS, Lee CH. Treatment of osteomyelitis caused by fracture of the mandible. J Korean Assoc Maxillofac Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995; 17:277–282.

4. Heo NO, Park JH, Shin YG, Pang SJ, Jeon IS, Yoon KH. A case of the treatment of osteomyelitis following open reduction of mandibular fracture. J Korean Assoc Maxillofac Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996; 18:712–717.

5. Lee DJ, Choi MK, Oh SH, Lee JB. Conservative treatment of chronic suppurative osteomyelitis on mandibular body to condyle area: a case report. J Korean Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009; 35:474–480.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download