Abstract

Proliferative periostitis is a rare form of osteomyelitis that is characterized by new bone formation with periosteal reaction common causes of proliferative periostitis are dental caries, periodontitis, cysts, and trauma. While proliferative periostitis typically presents as a localized lesion, in this study, we describe an extensive form of proliferative periostitis involving the whole mandibular ramus and condyle. Because the radiographic findings were similar to osteogenic sarcoma, an accurate differential diagnosis was important for proper treatment.

Go to :

Proliferative reactions of the periosteum have been described using various terms, including Garre's osteomyelitis, proliferative periostitis of Garre, periostitis ossificans, osteomyelitis with proliferative periostitis, nonsuppurative ossifying periostitis, osteomyelitis sicca, and perimandibular ossification1. Proliferative periostitis is a rare disease, and represents new bone formation with periosteal reaction. The common causes of periosteal reaction are dental caries with associated periapical lesions and secondary periodontal infections, fracture, and nonodontogenic infections2. The most prevalent areas are the premolar and molar areas of the mandible3. Radiographically, radiopaque lamination is observed parallel to the surface of the cortical bone4. The number of laminations varies from 1 to 12, and radiolucent separation is seen between the newly formed bone and the original cortical bone2. Less frequently, osteolytic radiolucency and sequestra are observed in the newly formed bone2. Most lesions are localized around the buccal cortex of the teeth which the periostitis originates3456.

The most common treatment for this disease involves eliminating the origin of infection. Extraction and endodontic therapy around the involved tooth have been described as successful methods to treat the odontogenic origin of proliferative periostitis57. The newly formed bone is consolidated within 6 to 12 months after eliminating the origin of infection and is remodeled by overlying muscle2. A broad differential diagnosis is necessary for determining the treatment plan and may include fibrous dysplasia, Ewing's sarcoma, osteogenic sarcoma, ossifying hematoma, exostosis, and osteoma8.

We present a case of extensive proliferating periostitis that resembled osteogenic sarcoma.

Go to :

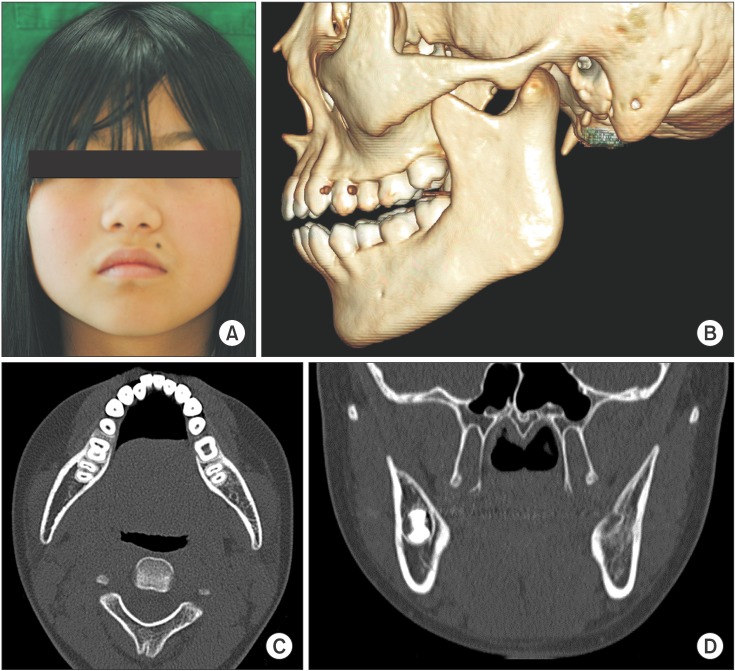

An 11-year-old girl was referred from a local clinic for swelling of the left mandibular area that began one month prior.(Fig. 1) She presented with trismus and facial asymmetry due to swelling of the left mandibular angle and condyle area; however, there was no tenderness, fever, or redness. She had no history of trauma to the left facial area. On intraoral examination, there were no dental caries or periodontal lesions. However, there was mild swelling and tenderness of the distal gingiva on the left mandibular second molar. The third molar was impacted.

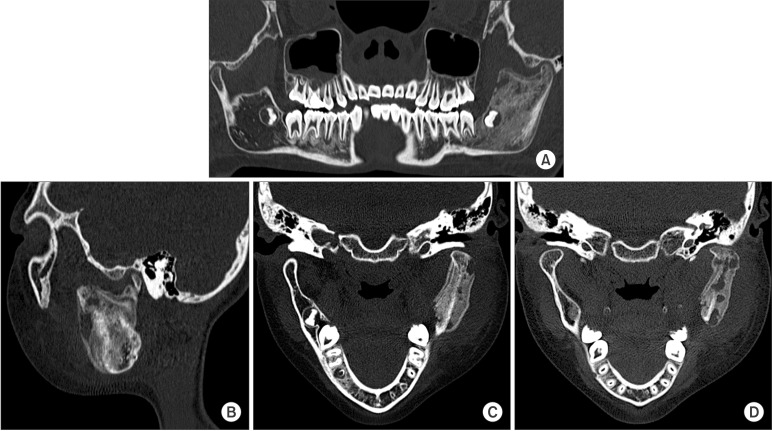

A panoramic view showed the unerupted third molar on the left mandible and a radiolucent appearance of the ascending ramus. A sclerotic appearance was observed over the left mandibular body, ramus, and condyle. Because of the bony sclerotic change, the cortical bone of the left mandibular canal was faint compared to the corresponding area on the right side.(Fig. 2) This feature can be observed in detail on the computed tomography (CT) image.(Fig. 3) There was an osteolytic and sclerotic bone lesions in the left mandibular body, ramus, and condyle area.(Fig. 3. A, 3. B) New bone formation with periosteal reactions was observed in the medial and lateral portion of the condyle.(Fig. 3. C) It was more dominant in the lateral portion. Osteolytic change was also observed inside the newly formed bone.(Fig. 3. D) The left masseter muscle showed swelling and contrast enhancement. On laboratory testing, the C-reactive protein (CRP) level was 2.0 mg/dL, white blood cells (WBC) count was 11.2×103/mm3 and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 104 mm/hr. These values were greater than the normal ranges.

From these clinical and radiological features, the initial diagnosis was osteogenic sarcoma with an initial treatment plan of hemimandibulectomy with costochondral graft. To obtain a proper diagnosis, we performed an incisional biopsy on the left mandible area under local anesthesia. Histologically, acute and chronic inflammation with reactive new bone formation was observed. Based on the pathological findings, the initial diagnosis was revised to an extensive form of proliferative periostitis.

Under general anesthesia, a vestibular incision was made starting from the left mandible outer oblique ridge area. Subperiosteal dissection was performed inferiorly and posteriorly to expose the mandibular angle. After adequate exposure of the coronoid process, a coronoidectomy was performed to properly approach to the condylar area. The newly formed bone overlying the cortical bone of the ramus was identified, and decortication was performed. The impacted third molar was extracted, and the removed specimens were sent for biopsy.

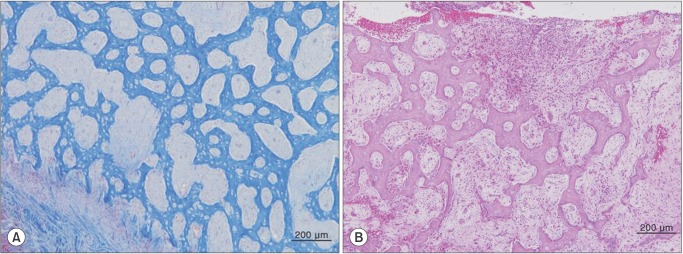

Histological examination showed new trabecular bone formation with osteoblastic rimming. The individual bony trabeculae of the reactive woven bone were arranged perpendicular to the bone surface.(Fig. 4. A) The intertrabecular space was occupied by a dense fibrous stroma with chronic inflammatory infiltrates and necrosis.(Fig. 4. B) From these features, the mandibular lesion was diagnosed as osteomyelitis with proliferative periostitis.

Amoxicillin was prescribed following surgery. Ten days after surgery, the patient did not feel any particular discomfort, and the surgical wound showed was in a good healing state. The trismus also showed improvement. The laboratory tests returned to normal ranges. The CRP level was 0.13 mg/dL, WBC count was 6.7×103/mm3, and ESR was 39 mm/hr. One month after surgery, the left mandibular angle area showed normal facial contour, and the trismus had disappeared. At 11-month follow-up, there was no sign of recurrence or facial contour abnormality.(Fig. 5. A) On CT imaging, the newly formed bone and sclerotic change of the mandibular ramus and condyle area had disappeared.(Fig. 5. B, 5. C) Additionally, the extraction socket of left mandibular third molar completely healed.(Fig. 5. D)

She agreed to have her clinical photographs being published on this paper.

Go to :

Proliferative periostitis is a form of chronic osteomyelitis that involves new periosteal bone formation over the cortical bone. The most common cause of proliferative periostitis is odontogenic infection2. Most proliferative periostitis occurs over the cortical bone and the area of the involved tooth but in a localized form3. Some reports used only occlusal radiography to make a diagnosis of this disease without biopsy or further radiological examination34. A case of extensive bone formation over the involved area has never been reported. In this case, periosteal bone formation extended beyond the involved areas into the left mandibular ramus and condyle.

Usually, proliferative periostitis originates from a periapical lesion associated with dental caries or periodontal infection3. Rarely, proliferative periostitis has been reported to occur due to an unerupted third molar6. According to Neville et al.2, periosteal hyperplasia can be caused by an unerupted tooth near the lesion. In this patient, the developing third molar was suspected to be the source of infection, and proliferative periostitis was observed adjacent to the unerupted third molar.(Fig. 2)

In the CT image, osteolytic change was observed inside the newly formed bone.(Fig. 3) Generally, proliferative bone forms layers of radiopaque lamination, like "onion skin". Cortical bone lamination should be arranged in parallel layers3. Less frequently, osteolytic radiolucencies are found in the new bone7. In our patient, the outer surface of the newly formed bone was smooth and continuous (Fig. 3. C); however, a bony, destructive and sclerotic appearance was observed inside the new bone, which was dominant on the lateral portion.(Fig. 3. D) This bony change also appears in Ewing's sarcoma and osteogenic sarcoma8, but the bony destruction involved in those diseases is more irregular and has a moth-eaten appearance28. Additionally, the periosteal reaction is typically seen as a sun burst or sun ray appearance as opposed to lamination of cortical bone28.

Histologically, parallel rows of trabeculae in reactive, woven bone formed perpendicularly to the cortical bone surface, and inflammation and necrosis were observed in the intertrabecular space. In proliferating periostitis, the individual trabecular bone is sometimes interconnected and widely distributed2, which is similar to the pattern of immature fibrous dysplasia9. However, in fibrous dysplasia, the trabeculae of woven bone are irregularly shaped, and a fibrous stroma is seen. Furthermore, in osteogenic sarcoma, anaplastic tumor cells and osteoid produced by malignant mesenchymal cells can be observed2. However, there was no osteoid production or tumor cells in this case.

Treatment options for proliferative periostitis typically include removal of the infected tooth or endodontic treatment346. After eliminating the source of the infection, the enlarged bone is remodeled back to its original form by the action of overlying muscle2. If the osseous enlargement is too severe and remodeling to the original form is unlikely, surgical intervention is needed to contour the enlarged bone10. In this case, the source of infection was removed by extraction of the left mandibular third molar, and an outer decortication was performed to remove sclerotic bone and for aesthetic reasons. The patient's face recovered, and regained normal symmetric contours one month after surgery. Eleven months after surgery, new bone formation on the ramus and condyle completely disappeared.(Fig. 5) Although the sclerotic change extended broadly from the mandibular ramus to the condyle, we could easily treat this case by simple tooth extraction and decortication without radical resection.

In conclusion, this case demonstrates that proliferative periostitis can occur due to infection around an unerupted tooth. In this patient, the periosteal reaction was seen extensively from the mandibular ramus to the condyle. The sclerotic and osteolytic bony change presented inside the newly formed bone. We used CT imaging and incisional biopsy to make an initial diagnosis. Based on these results, we performed extraction of the unerupted tooth and subsequent decortication.

Go to :

Notes

Conflict of Interest: This work was supported by a grant from the Next-Generation BioGreen21 Program (No.PJ01121404), Rural Development Administration, Republic of Korea.

Go to :

References

1. Langlais RP, Langland OE, Nortjé CJ. Diagnostic imaging of the jaws. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins;1995.

2. Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM. Oral and maxillofacial pathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders;2002.

3. Zand V, Lotfi M, Vosoughhosseini S. Proliferative periostitis: a case report. J Endod. 2008; 34:481–483. PMID: 18358903.

4. Jacobson HL, Baumgartner JC, Marshall JG, Beeler WJ. Proliferative periostitis of Garré: report of a case. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002; 94:111–114. PMID: 12193904.

5. Ebihara A, Yoshioka T, Suda H. Garrè's osteomyelitis managed by root canal treatment of a mandibular second molar: incorporation of computed tomography with 3D reconstruction in the diagnosis and monitoring of the disease. Int Endod J. 2005; 38:255–261. PMID: 15810976.

6. Tong AC, Ng IO, Yeung KM. Osteomyelitis with proliferative periostitis: an unusual case. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006; 102:e14–e19. PMID: 17052617.

7. Nortjé CJ, Wood RE, Grotepass F. Periostitis ossificans versus Garrè's osteomyelitis Part II: radiologic analysis of 93 cases in the jaws. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1988; 66:249–260. PMID: 3140161.

8. Wood NK, Goaz PW. Differential diagnosis of oral and maxillofacial lesions. 5nd ed. St Louis: Mosby;1997.

9. Petrocelli M, Kretschmer W. Conservative treatment and implant rehabilitation of the mandible in a case of craniofacial fibrous dysplasia: a case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014; 72:902.e1–902.e6. PMID: 24742486.

10. Belli E, Matteini C, Andreano T. Sclerosing osteomyelitis of Garré periostitis ossificans. J Craniofac Surg. 2002; 13:765–768. PMID: 12457091.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download