Abstract

Coronoid process hyperplasia is a rare condition that causes mouth opening limitation, otherwise known as trismus. The elongated coronoid processes impinge on the medial surfaces of the zygomatic arches when opening the mouth, which limits movement of the mandible and leads to trismus. Patients with trismus due to coronoid process hyperplasia do not have any definite symptoms such as temporomandibular joint pain or sounds upon clinical examination, and no significant abnormal signs are observed on panoramic radiographs or magnetic resonance images of the temporomandibular joint. Thus, the diagnosis of trismus is usually very difficult. However, computed tomography can help with the diagnosis, and the condition can be treated by surgery and postoperative physical therapy. This paper describes four cases of patients who visited our clinic for trismus and were subsequently diagnosed with coronoid process hyperplasia. Three were successfully treated with a coronoidectomy and postoperative physical therapy.

Go to :

Mouth opening limitation can be caused by a variety of factors, although most cases involve anterior disc displacement without reduction, masticatory muscle disorders, or temporomandibular joint (TMJ) osteoarthritis. For patients with these disorders, mouth opening limitation can improve with conservative treatments such as self-care, medication, or the use of a stabilizing splint. However, if symptoms persist, other etiologies should be considered.

Coronoid process hyperplasia is a rare cause of mouth opening limitation; it is characterized by the impingement of the elongated coronoid processes on the medial surfaces of the zygomatic arches with mouth opening. Early diagnosis and proper treatment planning are important to reduce patient discomfort and avoid wasting time and money on repeated conservative treatments, which would be ineffective since only surgical treatments such as coronoidotomy or coronoidectomy are successful in treating this malady.

This paper describes four cases of continuous mouth opening limitation due to coronoid process hyperplasia. All occurred despite repeat conservative treatments. The diagnosis and treatment of the condition are also discussed. Institutional review board approval was granted in Yonsei University, Gangnam Severance Hospital (IRB #3-2014-0019).

Go to :

A 43-year-old man visited the clinic for mouth opening limitation that had persisted for 30 years. The patient's medical history was unremarkable, and he had no previous history of surgery or trauma.

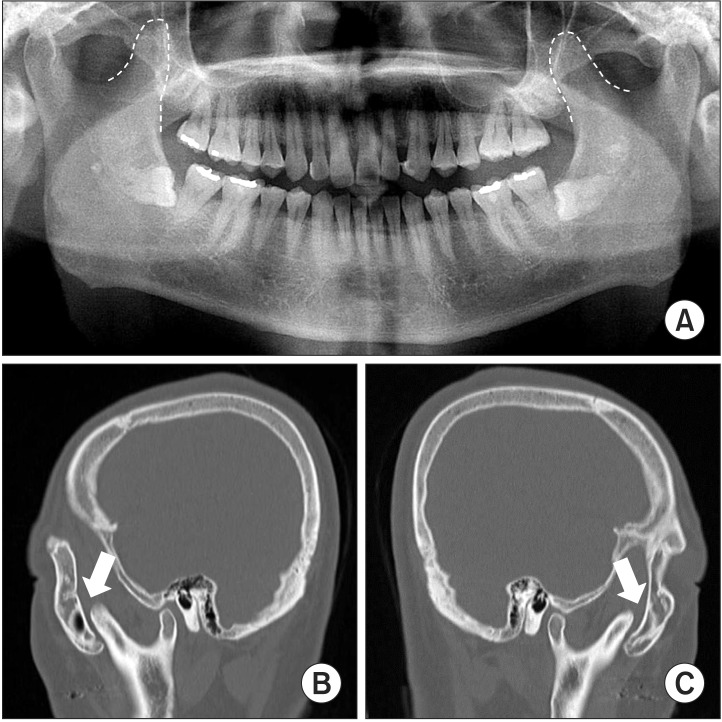

The maximal interincisal opening (MIO) was 25 mm. He had no TMJ sounds or pain, although stiffness of the bilateral masseter muscles was noted. Initially, it was hypothesized that his symptoms were due to anterior disc displacement without reduction and a masticatory muscle disorder; magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed to assess the positions of the articular discs. The MRI did not reveal any detectable disc displacement, so the panoramic radiograph was reassessed to identify the cause of the mouth opening limitation.(Fig. 1. A) Computed tomography (CT) scans were also performed, revealing elongated bilateral coronoid processes and heterotopic bone formation on the medial and inferior surfaces of the bilateral zygomatic arches.(Fig. 1. B, 1. C) The necessity of a coronoidectomy was emphasized when consulting with the patient, but the patient did not return to the clinic.

A 21-year-old man visited the clinic due to a limited MIO of 28 mm and pain in the left TMJ when chewing and opening his mouth. The patient had undergone orthodontic treatment for several years before visiting the clinic and had a history of stabilizing splint therapy in an oriental medical clinic.

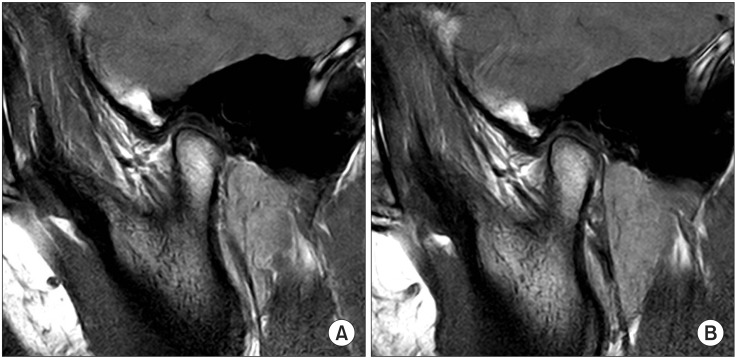

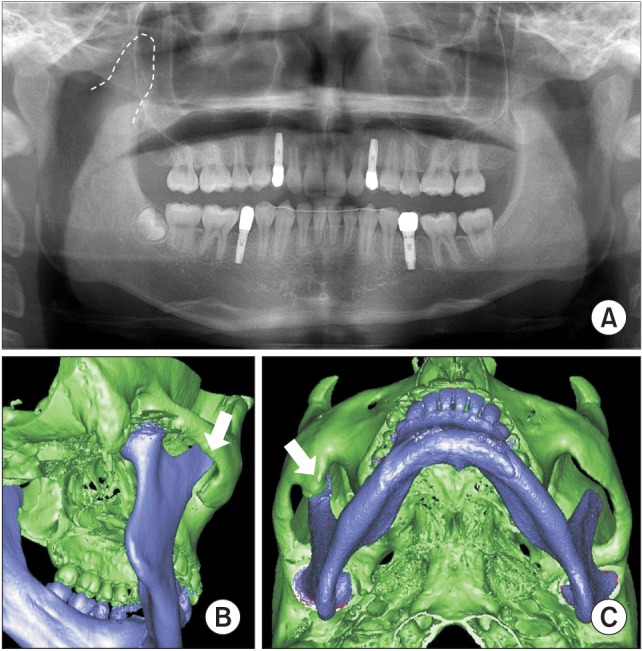

Magnetic resonance images were obtained with the expectation that anterior disc displacement without reduction and a masticatory muscle disorder were responsible for the patient's condition, based on physical examinations.(Fig. 2. A, 2. B) The images revealed anterior disc displacement with reduction on the left TMJ and adhesion of the right articular disc. Anterior positioning splint therapy and botulinum toxin injection were used to relieve the stiffness of the bilateral masseter muscles, but no improvement in TMJ pain or MIO was observed. Arthroplasty of the right TMJ was performed to resolve the adhesion of the articular disc, but the movement of the mandible was not satisfactory in the operating room. A few months after surgery, the patient continued to complain of TMJ pain, a grinding sound in the bilateral TMJs, and mouth opening limitation. CT images were taken to determine the possibility of TMJ osteoarthritis or neoplasm, and an elongated right coronoid process and heterotopic bone formation were detected on the medial and inferior surfaces of the right zygomatic arch.(Fig. 3A-C)

The patient underwent a right coronoidectomy under general anesthesia, and the heterotopic bone was removed. Immediately after surgery, the MIO was increased to 43 mm in the operating room. Physical therapy was initiated three weeks postoperatively; at the 15-month follow-up visit, the patient's MIO was found to have increased to 63 mm with protrusive and lateral movements to the right and left of 7 mm, 10 mm, and 7 mm, respectively. No specific abnormality was noted except for a slight right deviation when opening the mouth, multiple grinding sounds from the left TMJ, and mild pain in the right masseter muscle.

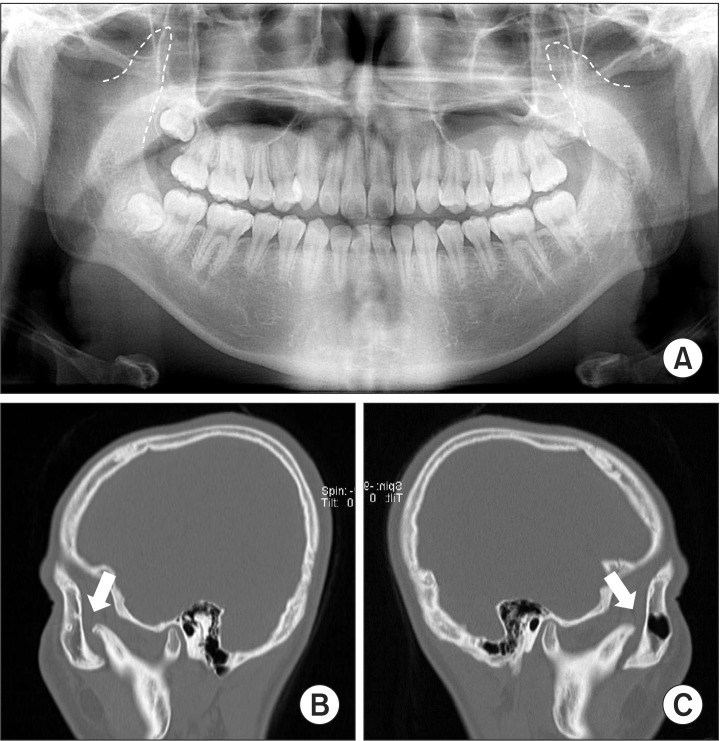

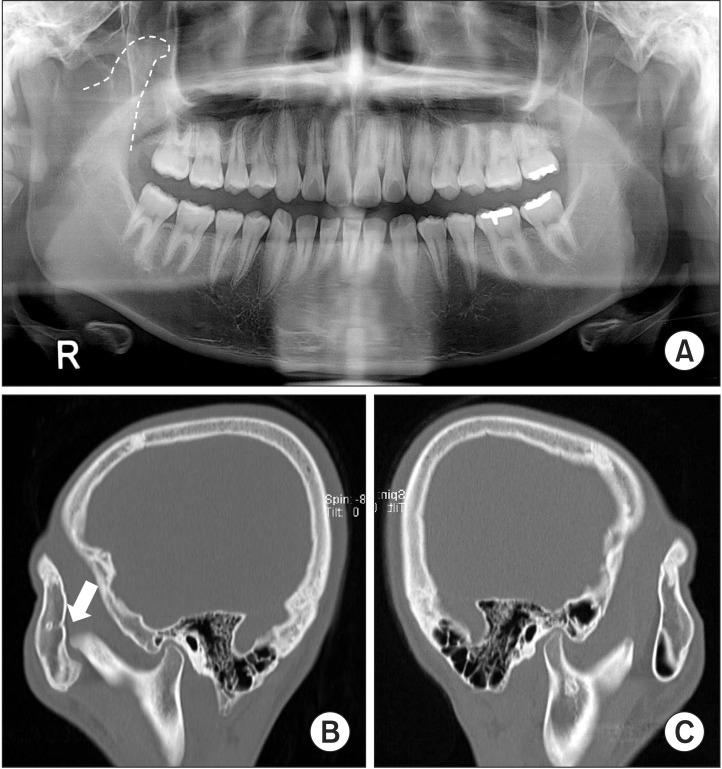

A 19-year-old man visited our clinic for mouth opening limitation that had persisted for four years. Upon initial examination, he was found to have a limited MIO of 32 mm and crepitus sounds in the bilateral TMJs, but no pain on palpation of the TMJ or with jaw opening and closing. Osteoarthritis of the TMJ was suspected based on a panoramic radiograph (Fig. 4. A), so an MRI was obtained. However, the bilateral TMJ discs were in the normal position, and only a slight erosive change was found on the superior surface of the left condyle. It was difficult to determine whether the erosive change on the left condyle was the direct cause of mouth opening limitation, so CT scans taken at another hospital were assessed to determine whether there was any elongation of the coronoid processes. Elongation of the bilateral coronoid processes was confirmed, and heterotopic bone formation was observed on the medial and inferior surfaces of the bilateral zygomatic arches.(Fig. 4. B, 4. C)

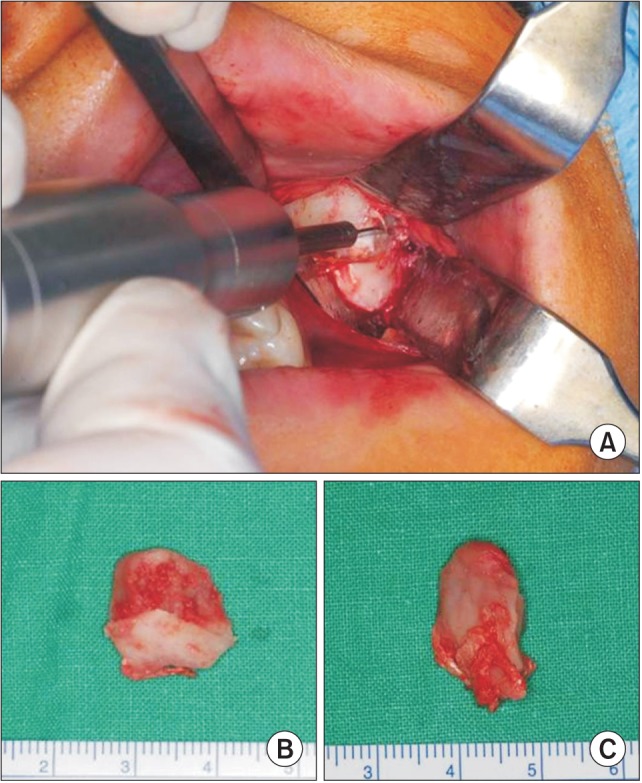

A bilateral coronoidectomy was performed, and the heterotopic bone was removed under general anesthesia.(Fig. 5) Immediately after surgery, the MIO had increased to 35 mm in the operating room. Physical therapy was initiated two weeks postoperatively, and muscle relaxants were prescribed to relax the masticatory muscle. At the 18-month follow-up visit, the patient's MIO had increased to 65 mm with protrusive and lateral movements to the right and left of 5 mm, 7 mm, and 5 mm, respectively. No TMJ sounds could be heard.

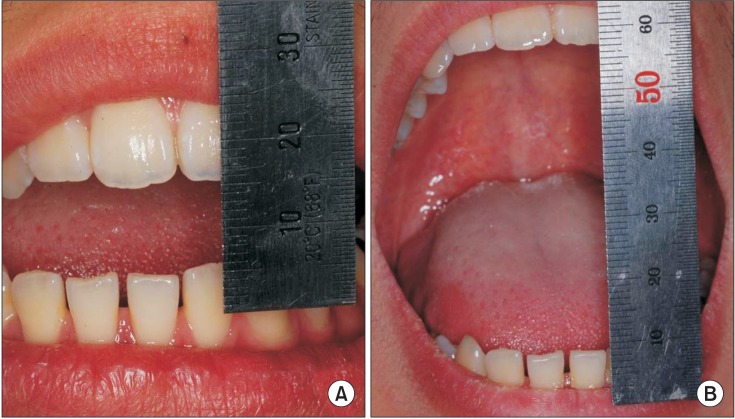

An 18-year-old man visited our clinic for mouth opening limitation that had persisted for six months. Attempts to increase mouth opening by manipulation, medication, and a stabilizing splint were not successful. The MIO was 12 mm (Fig. 6. A), and there were no sounds or pain in the TMJ. Due to the lack of improvement in the MIO despite a long period of conservative treatment, CT scans were obtained, and elongation of the right coronoid process was confirmed.(Fig. 7)

A right coronoidectomy was performed, and physical therapy was initiated three weeks postoperatively. At the 15-month follow-up visit, the MIO was increased to 54 mm (Fig. 6. B), the protrusive and lateral right and left movements were 6 mm, 10 mm, and 8 mm, respectively, and the patient reported that he no longer felt any discomfort.

Go to :

There have been many reports of coronoid process hyperplasia in males, and some authors have noted that the condition is a sex-linked trait1. However, subsequent cases have been noted in females2,3. All of the cases discussed here were adolescent males, and McLoughlin et al.4 have noted that men are more commonly affected than women.

Several factors have been thought to be associated with coronoid process hyperplasia, including endocrine stimulation, genetic inheritance, and trauma5,6,7,8. However, hypotheses involving increased activity of the temporal muscles have received the most support9. It has been reported that, when the mandibular movement is limited by permanent TMJ disc displacement or TMJ ankylosis, compensatory hyperactivity of the temporal muscles occurs, leading to coronoid process hyperplasia10. In the present study, MRI was performed for cases 1, 2, and 3, and no articular disc displacement was observed except in case 2, which showed anterior disc displacement with reduction of the left TMJ. In addition, it was initially difficult to identify the reason for each patient's trismus because, in the absence of classic associations like condylar fracture or TMJ ankylosis, no obvious reason for hyperactivity of the temporal muscles could be identified. A consideration of the differential diagnosis for fibrous ankylosis was thus important.

The initial clinical examination of patients with mouth opening limitation is very important for selecting the appropriate diagnostic modalities. Patients with coronoid process hyperplasia rarely complain of symptoms such as TMJ pain or sounds or of the masticatory muscle pain that is commonly reported in temporomandibular or masticatory muscle disorders. Previous studies have reported that only a small percentage of these patients complain of pain (7%) and crepitation (8%) with mouth opening at the initial clinical examination11. Mulder et al.9 reported that, if patients complain of pain, crepitation in the zygomatic area, or a hard end feel when opening their mouth at the initial clinical examination, coronoid process hyperplasia should be suspected. In the present study, two patients had no symptoms of pain, and no sounds were heard when they opened their mouth; one patient experienced only crepitus sounds, and the final patient complained of pain in the left TMJ, felt no pain in the right TMJ (the site of coronoid process hyperplasia), and had no audible sounds with jaw movement. These findings indicate that, if a patient with mouth opening limitation has 1) no symptoms related to a temporomandibular or masticatory muscle disorder, 2) a hard end feel when opening the mouth, 3) pain in the zygomatic area when opening the mouth, and 4) no improvement of symptoms despite repeated conservative treatment, it can be assumed that coronoid process hyperplasia is responsible for the mouth opening limitation.

Various diagnostic modalities have been suggested for patients with mouth opening limitation caused by coronoid process hyperplasia. Some authors have reported that using a Water's view radiograph in the mouth open position2 or comparing the distance between the horizontal line of the coronoid process and the horizontal line of the condyle head using Levandoski panoramic radiograph analysis12,13 could be useful diagnostic methods when plain X-rays are used. Kubota et al.13 measured the ratio between the length of the coronoid process and the length of the condylar process of patients with coronoid process hyperplasia and a control group using Levandoski panoramic radiograph analysis and reported that a ratio greater than 1.1 indicates that further evaluation is necessary because coronoid process hyperplasia is likely. However, the anatomic structures shown in panoramic radiographs are subject to distortion, so the diagnostic methods mentioned above are suitable for use as a reference when diagnosing coronoid process hyperplasia, but they cannot play a crucial role in the diagnosis. Creating plastic models of the skull, such as the rapid prototyping model, has also been reported as a suitable diagnostic method but is of limited use given the costs involved14. Recently, cone-beam CT has been preferred over conventional CT for diagnosis due to the low dose of radiation used and the relatively low cost12.

Currently, the most popular diagnostic method is CT, and most clinicians have used CT to confirm the diagnosis of coronoid process hyperplasia8,15,16,17. CT scans were obtained for all of the cases presented here, and elongated coronoid processes were found in all four cases. Additionally, heterotopic bone formation was identified on the medial and inferior surface of the zygomatic arch in the sagittal view of the CT images of cases 2 and 3. In the axial view, the tops of the coronoid processes were higher than the superior surface of the zygomatic arch, and this could also be used to identify coronoid process hyperplasia. Therefore, when patients show the signs mentioned above and also have elongated coronoid processes observed in panoramic radiographs, CT will be the most reliable method for confirming the diagnosis.

Coronoidectomy can be accomplished using intraoral and extraoral approaches. The intraoral approach has the advantages of providing sufficient access without producing any extraoral scar, and it is preferred in most cases despite the risk of postoperative hematoma formation or subsequent fibrosis4. An endoscopy-assisted intraoral approach can reportedly reduce the complications associated with the intraoral approach described above16. In the present report, an intraoral approach was used for the three patients who underwent surgery, and no remarkable postoperative complications were noted. Application of ice packs or a steroid injection to reduce postoperative swelling and physical therapy for preventing fibrosis are important components of postoperative care.

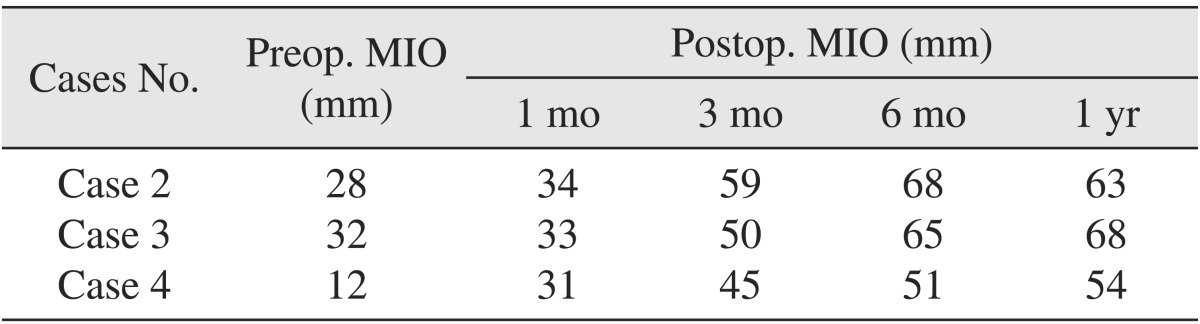

Postoperative physical therapy is very important for obtaining a good result after coronoidectomy4,11. Regrowth of the previously resected coronoid process, hematoma formation, or fibrosis may lead to an unsatisfactory prognosis18. McLoughlin et al.4 emphasized the importance of postoperative physical therapy based on a study in which only half of the treated patients achieved an MIO greater than 30 mm. A spatula, wedge, and TheraBite Jaw Motion Rehabilitation System (ATOS Medical, Hörby, Sweden) are currently used for physical therapy19. In the present study, patients began with light mouth opening exercises 2 to 3 weeks after surgery, and active physical therapy with accompanying lateral and protrusive movements of the jaw was started 3 to 5 weeks after surgery. The importance of physical therapy was stressed at each weekly visit; consequently, satisfactory improvements in MIO were achieved.(Table 1)

Medication is also important for obtaining good results after coronoidectomy. Smyth and Wake15 prescribed diphosphonates (Didronel; Norwich Pharmaceuticals Inc., North Norwich, NY, USA) for three months postoperatively to a patient who had recurrent coronoid process hyperplasia after the first coronoidectomy and successfully avoided a further recurrence. Diphosphonates suppress alkaline phosphatase levels and reduce bone turnover and osteoblast activity. Muscle relaxants were prescribed for cases 2 and 3 in order to enhance the effect of postoperative physical therapy because both patients had difficulty performing physical therapy due to stiffness of the jaw-opening muscles, likely due to the chronic nature of their mouth opening limitation. The follow-up results were satisfactory.

Patients with mouth opening limitation suspected to be due to coronoid process hyperplasia after initial clinical and radiographic examinations should undergo CT for an accurate diagnosis. Ineffective long-term conservative care from the misdiagnosis of coronoid process hyperplasia is not only costly, but it can also lead to patient discomfort and wasted time. After coronoidectomy, continuous and active physical therapy, medications including muscle relaxants, and regular check-ups can help achieve a good outcome.

Go to :

References

1. Marra LM. Bilateral coronoid hyperplasia, a developmental defect. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1983; 55:10–13. PMID: 6572342.

2. Kreutz RW, Sanders B. Bilateral coronoid hyperplasia resulting in severe limitation of mandibular movement. Report of a case. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1985; 60:482–484. PMID: 3864110.

3. Kraut RA. Bilateral coronoid hyperplasia: report of two cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1985; 43:612–614. PMID: 3859611.

4. McLoughlin PM, Hopper C, Bowley NB. Hyperplasia of the mandibular coronoid process: an analysis of 31 cases and a review of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1995; 53:250–255. PMID: 7861274.

5. Rowe NL. Bilateral developmental hyperplasia of the mandibular coronoid process. A report of two cases. Br J Oral Surg. 1963; 1:90–104. PMID: 14089492.

6. Sarnat BG, Feigenbaum JA, Krogman WM. Adult monkey coronoid process after resection of trigeminal nerve motor root. Am J Anat. 1977; 150:129–137. PMID: 412408.

7. van Hoof RF, Besling WF. Coronoid process enlargement. Br J Oral Surg. 1973; 10:339–348. PMID: 4516118.

8. Kai S, Hijiya T, Yamane K, Higuchi Y. Open-mouth locking caused by unilateral elongated coronoid process: report of case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1997; 55:1305–1308. PMID: 9371124.

9. Mulder CH, Kalaykova SI, Gortzak RA. Coronoid process hyperplasia: a systematic review of the literature from 1995. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012; 41:1483–1489. PMID: 22608198.

10. Isberg AM, McNamara JA Jr, Carlson DS, Isacsson G. Coronoid process elongation in rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) after experimentally induced mandibular hypomobility. A cephalometric and histologic study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1990; 70:704–710. PMID: 2263326.

11. Wenghoefer M, Merkx M, Steiner M, Götz W, Meijer GJ, Bergg SJ. Hyperplasia of the coronoid process. Asian J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006; 18:51–58.

12. Costa YM, Porporatti AL, Stuginski-Barbosa J, Cassano DS, Bonjardim LR, Conti PC. Coronoid process hyperplasia: an unusual cause of mandibular hypomobility. Braz Dent J. 2012; 23:252–255. PMID: 22814695.

13. Kubota Y, Takenoshita Y, Takamori K, Kanamoto M, Shirasuna K. Levandoski panographic analysis in the diagnosis of hyperplasia of the coronoid process. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1999; 37:409–411. PMID: 10577758.

14. Asaumi J, Kawai N, Honda Y, Shigehara H, Wakasa T, Kishi K. Comparison of three-dimensional computed tomography with rapid prototype models in the management of coronoid hyperplasia. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2001; 30:330–335. PMID: 11641732.

15. Smyth AG, Wake MJ. Recurrent bilateral coronoid hyperplasia: an unusual case. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1994; 32:100–104. PMID: 8199139.

16. Robiony M, Casadei M, Costa F. Minimally invasive surgery for coronoid hyperplasia: endoscopically assisted intraoral coronoidectomy. J Craniofac Surg. 2012; 23:1838–1840. PMID: 23147302.

17. Tavassol F, Spalthoff S, Essig H, Bredt M, Gellrich NC, Kokemüller H. Elongated coronoid process: CT-based quantitative analysis of the coronoid process and review of literature. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012; 41:331–338. PMID: 22192388.

18. Bronstein SL, Osborne JJ. Mandibular limitation due to bilateral coronoid enlargement: management by surgery and physical therapy. Cranio. 1984-85; 3:58–62. PMID: 6594401.

19. Fernández Ferro M, Fernández Sanromán J, Sandoval Gutierrez J, Costas López A, López de Sánchez A, Etayo Pérez A. Treatment of bilateral hyperplasia of the coronoid process of the mandible. Presentation of a case and review of the literature. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2008; 13:E595–E598. PMID: 18758406.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download