This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Abstract

Various surgical techniques, such as endoscopic surgery and robotic surgery, are developed to optimize the esthetic outcome even in operations for malignancy. A modified face-lift or retroauricular approach are used to minimize postoperative scarring. Recently, robot-assisted surgery is being done in various fields and considered as favorable treatment method by many surgeons. However its high cost is a nonnegligible fraction for many patients. On the other hand, endoscopic surgery, which is cheaper than robotic surgery, is minimally invasive with contentable neck dissection. Although it is a difficult technique for a beginner surgeon due to its limited operation view, we suppose it as an alternative method for robotic surgery. Herein, we report two cases of endoscopic neck dissection via retroauricular incision with a discussion regarding the pros and cons of endoscopic neck dissection.

Go to :

Keywords: Endoscopes, Neck dissection, Head and neck cancer

I. Introduction

Various surgical techniques have been developed to optimize esthetic outcomes even in operations for malignancy. Unlike other parts of the body, postoperative scars are especially noticeable in the head and neck area. Thus, it is crucial to minimize postoperative scarring in these areas, especially in neck dissection (ND). Robot-assisted and endoscopic-assisted surgeries are typical examples. Kang et al.

1 first reported robot-assisted modified radical ND in 2010. They performed the operation via a transaxillary approach, but difficulties in approach to level I, an important area for oral cavity cancer treatment, were encountered

2. To overcome this limitation, ND via modified face-lift or the retroauricular approach using robotic surgery was attempted by the same author. Robot-assisted ND has many advantages, such as excellent esthetic outcomes and good visualization during surgery, but its high cost is a problem for most patients. Endoscopic-assisted surgery can be an alternative and more cost-effective option compared to robot surgery, as Byeon et al.

3 Recently, we treated two patients who underwent endoscopic-assisted ND via a retroauricular approach and had excellent esthetic outcomes. Herein, we report these cases and discuss the pros and cons of endoscopic ND.

Go to :

II. Cases Report

1. Case 1

A 63-year-old male patient visited the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery at Dental Hospital of Yonsei University of College of Dentistry in Korea. His chief complaint was an unhealed oral ulceration which appeared 8 months prior. Incisional biopsy had been performed by another hospital, which revealed invasive squamous cell carcinoma. The patient also had hypertension, for which he was receiving medication. He smoked two cigarettes a day for more than 30 years. The ulcerative lesion was present on the lingual side of #36, #37 and was 3.0×2.0 cm in size. The lesion had an irregular margin without bleeding tendency. Additional diagnostic imaging, including magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and positron-emission tomography (PET), were performed to determine extent of surgery. There was no mandibular or metastatic lymph node invasion, nor were there metastatic lesions on any other organs (cT2N0M0, stage II). Thus, wide excision with marginal mandibulectomy, selective neck dissection (SND) (I-III) via endoscope, and repair of the soft tissue defect with Megaderm (L&C Bio, Seongnam, Korea) were performed.

It took almost 5 hours to complete endoscope-assisted SND (I-III), with 450 cc of blood loss during the operation. The final diagnosis confirmed the initial clinical staging (pT2N0M0, stage II). There was mild marginal mandibular branch weakness, which might also have arisen in conventional ND. The patient was discharged 13 days after surgery without any other complications.

2. Case 2

A 56-year-old male was referred from a local clinic for evaluation of a tongue mass. It appeared 3 months prior and gradually increased in size. It was erosive and ulcerative with induration and bleeding tendency. He had no specific medical history. The patient had smoked 10 cigarettes a day for 15 years. An incisional biopsy was performed and confirmed a diagnosis of invasive squamous cell carcinoma. MRI and PET demonstrated no regional or distant metastasis (cT2N0M0, stage II). Consequently, wide excision with endoscopic ND, reconstruction of the surgical defect with a radial forearm free flap, and repair of the resulting forearm defect with Megaderm were performed.

It took almost 3.5 hours to complete endoscope-assisted SND (I-III), with 200 cc of blood loss during the operation. The final diagnosis confirmed the clinical staging (pT2N0M0, stage II). Unlike in case 1, no postoperative facial nerve weakness was observed. The patient was discharged 16 days after surgery without any complications.

3. Surgical procedure

Surgery was performed as described in a previous report

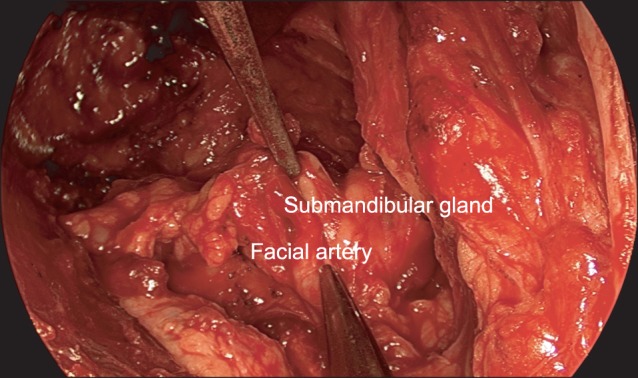

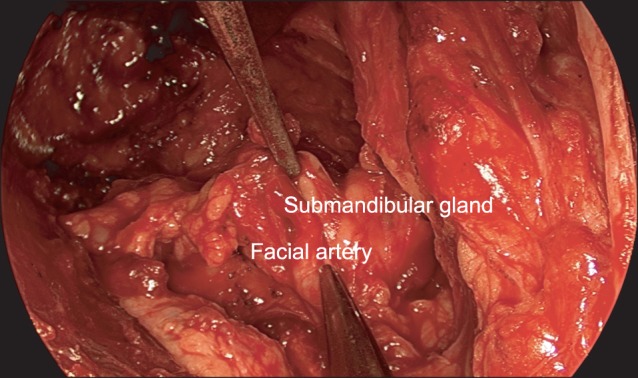

3. Under general anesthesia, the patient was placed in the supine position. Incision line and anatomical landmarks for endoscpoic neck dissection were outlined on patient's neck.(

Fig. 1) A retroauricualr incision was used to approach the sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM) and a skin flap was created. The SCM muscle was exposed, then we continued subplastysmal dissection inferiorly and anteriorly until we reach the omohyoid muscle, hyoid bone and the midline of the neck. During skin flap elevation, a self-retaining retractor (Sejong Medical Corporation, Paju; Sangdosa, Seoul, Korea) was used for good visualization of the surgical field. A nerve stimulator was used to identify the marginal mandibular branch of the facial nerve. We began ND with sufficient skin flap elevation. Level IIb was dissected under direct visualization with anterior retraction of the SCM muscle. Some portions of level Ib, IIa, and III were also dissected under direct visualization. Then, a 30-degree endoscope (10 mm in diameter, 30 cm in length; Stryker, San Jose, CA, USA) was applied in the level I area followed by fixation with an endoscope holder (Karl Storz, Tuttlingen, Germany).(

Figs. 2,

3)

| Fig. 1Patient position and design for retroauricular approach. Patient laid supine position with neck extension. Outline of sternocleidomastoid muscle, omohyoid muscle, inferior border of mandible, and incision line were identified.

|

| Fig. 2Preparation for endoscopic neck dissection. Self-retaining retractor was fixed and endoscope was being inserted into level Ib area.

|

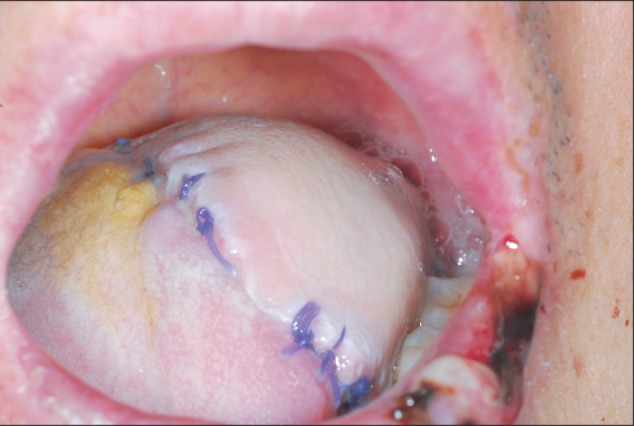

| Fig. 3Dissection on level Ib area (endoscopic view). Submandibular gland and facial artery were identified.

|

Dissection of the anterior belly area (level Ia) was performed; then, level Ib, which contains the submandibular gland, was dissected. Harmonic curved shears (Harmonic Ace 36P; Johnson & Johnson Medical, Cincinnati, OH, USA) were used to cauterize minor vessels and dissect tissues. The distal facial artery and vein were ligated with premium surgiclips (Covidien, Dublin, Ireland); the submandibular ganglion, Wharton's duct, proximal facial artery and vein were cut after ligation with surgiclips. The lingual artery and hypoglossal nerve were preserved. We demarcated the level of omohyoid muscle, which is inferior to the border of level III, and dissected lymphoadipose tissue superiorly from inferior margin using endoscope. Finally, dissection of the carotid artery and internal jugular vein was performed with posterior retraction of the SCM. It was possible to perform the final step under direct visualization. No remarkable bleeding or damage to important anatomical structures was observed.

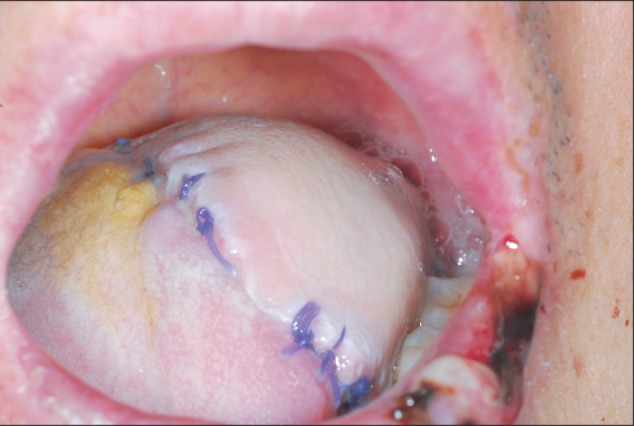

Micro-vascular surgery was performed in case 2 as usual manuals which have been done in conventional neck dissection.(

Fig. 4) Donor vessels such as the proximal portion of facial artery, superior thyroid artery, and related veins were observed well under microscope. No additional device was needed. However, an assistant had to retract the skin flap with an Army-Navy retractor for visualization of the operative field.

| Fig. 4Reconstructed tongue with radial forearm free flap (Case 2, postoperative day 17). Transplanted radial forearm free flap was survived successfully. Micro-anastomosis was performed via retroauricular approach. The color and texture was favorable.

|

Go to :

III. Discussion

Gagner

4 introduced endoscopic surgery as an alternative to conventional open neck surgery for parathyroidectomy in 1996. Since then, various trials for endoscopic surgery on the neck, including thyroidectomy

5, submandibular gland excision

6, sentinel node biopsy

7, and ND

3, have been performed. This technique was developed gradually and is currently used in the treatment of many patients.

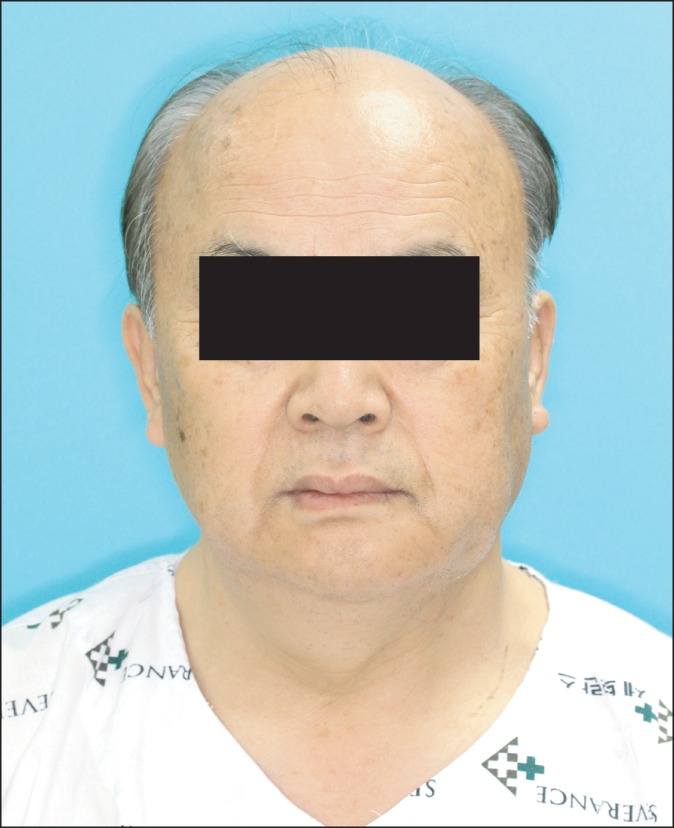

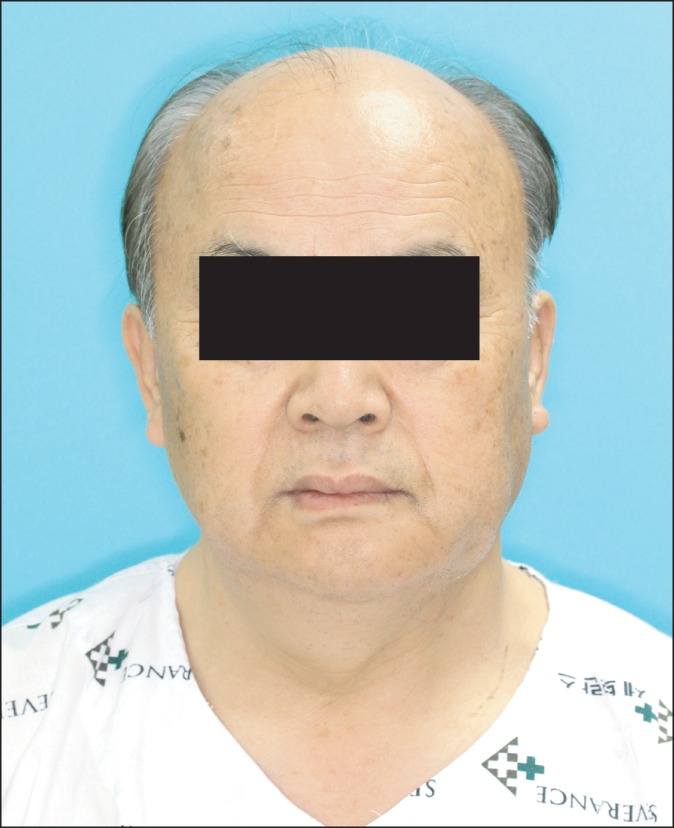

There are some advantages to endoscopic surgery compared to conventional methods. First of all, optimized esthetic outcomes are possible. Although postoperative period is not enough to discuss about results of postoperative scar, it cannot be seen easily in the frontal view because the incision line is hidden along the posterior neck.(

Figs. 5-

7) Second, the procedure is minimally invasive and patients typically recover faster. The incision line is also shorter than that of the conventional method. Although more retraction of the skin flap is needed and causes stretching of the flap, this did not lead to any postoperative complications in the present cases. Patients experienced less swelling and more rapid healing. We found that accurate ND could be obtained by the endoscopic approach. In the conventional method, it is difficult to dissect level IIb precisely, but the endoscopic approach provides the best field of view on level II and favorable fields of view on levels Ib and III.

| Fig. 5Clinical photograph (Case 1, frontal view, postoperative day 12). Postoperative scar is not identified at frontal photograph. Surgeons might achieve esthetic result after neck dissection.

|

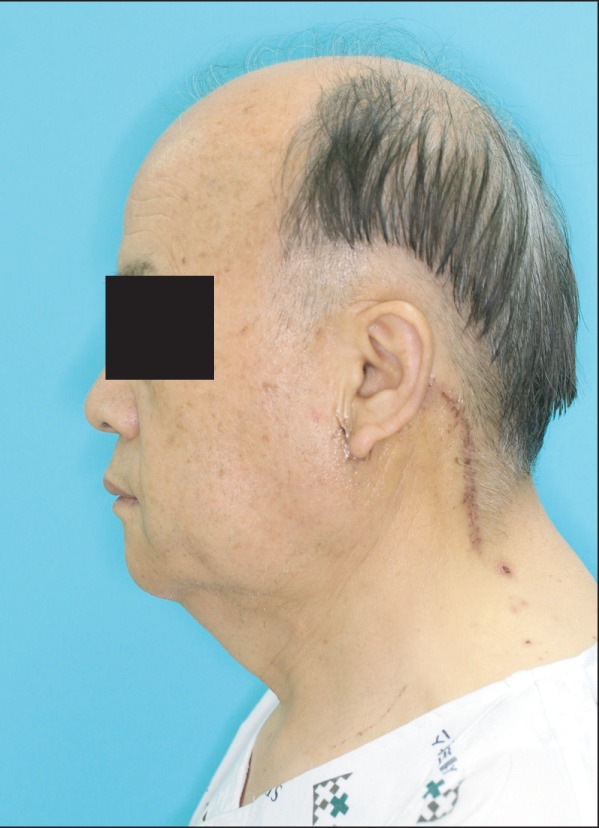

| Fig. 7Clinical photograph (Case 2, lateral view, postoperative day 17). The scar is relatively short compared with conventional methods and can also be hidden in hairline.

|

However, this technique may not be appropriate for unskilled operators who have less experience with endoscopy or are unfamiliar with surgical anatomy. Endoscopy provides limited direct visualization compared to the conventional method, so it can be difficult to recognize the exact area where is being operated and control unexpected hemorrhages. We should be especially careful when dissecting level Ia for two reasons. First, the overlying skin tends to be thin and punctured easily, since there is no platysma muscle on level Ia. Second, it is difficult to dissect the lymphoadipose tissues on level Ia precisely compared with the conventional method because of the limited surgical field. This technique may also not be appropriate for lesions on the floor of the mouth, near the midline, or along the anterior mandible where lymphatic drainage occurs to level Ia.

Byeon et al.

3 reported the advantages of robotic surgery compared with endoscopic surgery. First, they proposed that endoscopic surgery causes inconveniences to the operator and assistant due to limited space. Second, the robotic system has wrist articulated movement, which enables an unlimited operation field in a narrow working space compared to the endoscope. Third, the robotic system provides more assistance with its arm. However, its high cost is a distinct disadvantage of robotic surgery

3,

8. According to our experience, most patients diagnosed with oral cavity cancer are elderly, and are more concerned about cost than neck scarring.

Prominent postoperative scarring can be a major problem for patients. Robotic surgery provides minimal postoperative scarring, but is very expensive. Endoscopic ND is a little bit more expensive than the conventional approach, but cheaper than robotic surgery, and causes fewer scars compared to the conventional approach. Thus, we consider endoscopic ND as an alternative to robotic surgery in terms of cost and postoperative scarring. Oral and maxillofacial surgeons should make an effort to gain experience in endoscopic surgery and robotic surgery.

Unfortunately, there is no long-term follow-up information on patient outcomes involving these surgeries. Thus, it is impossible to compare oncologic outcomes between endoscopic ND and conventional ND. Further studies are required to gather more data on endoscopic ND.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download