Abstract

Objectives

Dislocation of the temporomandibular joint may occur for various reasons. Although different invasive methods have been advocated for its treatment, this study highlights the value of non-invasive treatment options even in chronic cases in a resource-poor environment.

Materials and Methods

A seven-year retrospective analysis of all patients managed for temporomandibular joint dislocation in our department was undertaken. Patient demographics, risk factors associated with temporomandibular joint dislocation and treatment modalities were retrieved from patient records.

Results

In all, 26 patients were managed over a seven-year period. Males accounted for 62% of the patients, and yawning was the most frequent etiological factor. Conservative treatment methods were used successfully in 86.4% of the patients managed. Two (66.7%) of the three patients who needed surgical treatment developed complications, while only one (5.3%) patient who was managed conservatively developed complications.

Conclusion

Temporomandibular joint dislocation appears to be associated with male sex, middle age, yawning, and low socio-economic status, although these observed relationships were not statistically significant. Non-invasive methods remain an effective treatment option in this environment in view of the low socio-economic status of the patients affected.

Go to :

The temporomandibular joint (TMJ) is a diarthrodial synovial joint of the hinge variety between the head of the mandibular condyle and the glenoid fossa on the cranial base. Translational (upper joint space) and rotational (lower joint space) movements (ginglymoarthrodial) occur within the joint and allow for protrusion/retrusion, depression/elevation and lateral excursion movements of the mandible1. The type (rotational, anterior translation, posterior translation, and mediolateral translation) and range of condylar movement within the TMJ is controlled by both active and passive forces, which include muscles, nerves and biomechanical constraints in the dentition as well as the TMJ with its associated ligaments2,3,4.

In certain conditions, the condylar head is displaced beyond the glenoid fossa in either an anterior, posterior, medial, lateral, or superior direction. This is referred to as dislocation, and it may be partial (subluxation) or complete (luxation or true dislocation)5. Subluxation is self reducible by the patient, while in cases of luxation, the patient requires assistance in restoring the normal joint position of the condylar head of the mandible6,7.

Dislocation of the mandibular condyle represents 3% of all reported dislocated joints in the body8 and has been variously classified based on symmetry (unilateral or bilateral), position (anterior, posterior, medial, lateral, and superior), number of occurrences (recurrent or non-recurrent), time of presentation (acute or chronic), and etiology (traumatic and non-traumatic or spontaneous). However, anterior dislocation is the most common type seen in clinical practice9,10,11.

Individuals in the second and third decades of life appear to be more predisposed to this condition9,12,13, though TMJ dislocation has been reported in children and the elderly14,15,16. Women are more likely to develop TMJ dislocation17,18, but the reason for this female predisposition is not yet fully understood.

The occurrence of TMJ dislocation has been noted in different clinical and everyday situations such as laughing, shouting, yawning, eating, epileptic and eclamptic fits, tooth brushing, vomiting, trauma, gastroendoscopy, general anesthesia, otorhinolaryngological and dental procedures, and transesophageal echocardiography11,19,20,21.

Different treatment modalities, both conservative and surgical, have been used to manage TMJ dislocation with varying success rates5,22,23. Although many studies have been conducted on TMJ dislocation, very few have been done in resource depleted environment. The aim of this retrospective study is to highlight the pattern of presentation of TMJ dislocation and the treatment modalities commonly used in our environment.

Go to :

All cases of TMJ dislocation seen at the Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Department of our University Teaching Hospital (Shika-Zaria, Kaduna, Nigeria) from 2007 to 2013 were retrospectively studied. Information retrieved from patients' case notes included age, sex, the immediate event preceding the dislocation, the type of dislocation, the treatment modality used, and any reported complications. TMJ dislocation was classified into acute, chronic (prolonged) and recurrent, according to Adekeye et al. (1976), while social class was defined using the United Kingdom National Socio-economic Classification (2010).

Data obtained were analyzed using the SPSS version 13.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and Microsoft Excel 2007 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA). Statistical analysis was performed using descriptive statistics (frequencies and crosstabs), with the test of a statistically significant relationship was set at a P-value less than 0.05.

Go to :

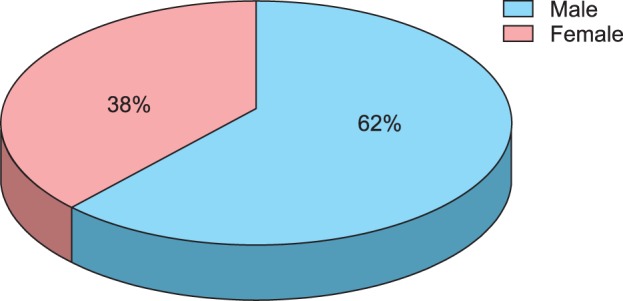

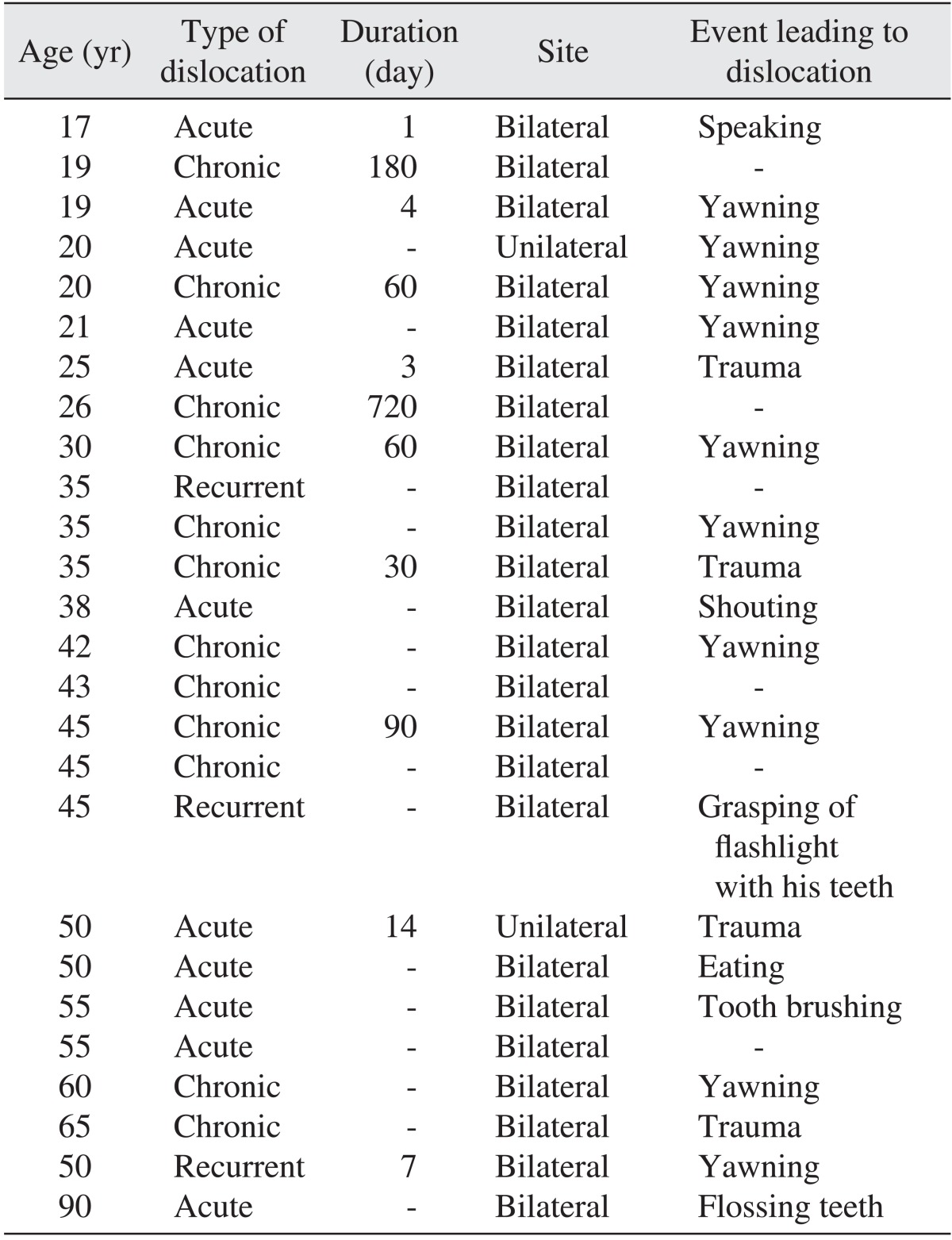

Within the period reviewed, 26 patients were seen, including 16 males (62%) and 10 females (38%), which produced a male : female ratio of 1.6 : 1.0.(Fig. 1) Patient ages ranged from 17 years to 90 years with a mean age of 39.8±17.3 years.(Table 1) Peak incidence was noted in patients in the fourth decade of life; however, although males predominated in most of the age groups, no statistically significant relationship was observed between the sex of the patients and their age group (P=0.483).

The socio-economic class of 22 patients whose occupations were documented showed that 19 (83.4%) belonged to analytical class 8 while 3 (13.6%) were of analytical class 7. There was no statistically significant relationship between social class status and TMJ dislocation (P=0.288). Acute and chronic dislocations were the most common types of presentation, accounting for 46.2% and 42.3%, respectively, of all the cases reviewed and were predominantly bilateral (96.2%). Similarly, there was no statistically significant relationship observed between the sex of patients and the type of dislocation (P=0.922).

Only three patients (11.5%) had a known underlying predisposing condition in the form of psychiatric illness. These patients were on antipsychotic therapy; one had been prescribed risperidone, and information regarding the pharmacological agents being used by the other two patients could not be obtained. An analysis of etiological factors in 20 of the patients (Table 1) showed yawning (50.0%) to be the main etiological factor followed by trauma (20.0%), but this difference was not statistically significant (P=0.266). The most common presentation was a class III skeletal relationship.(Fig. 2)

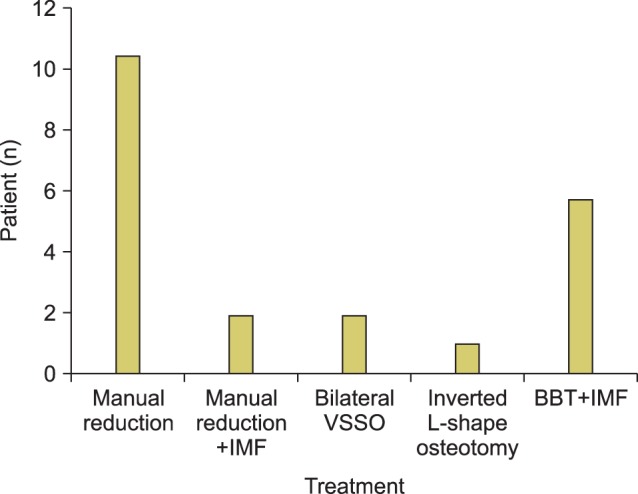

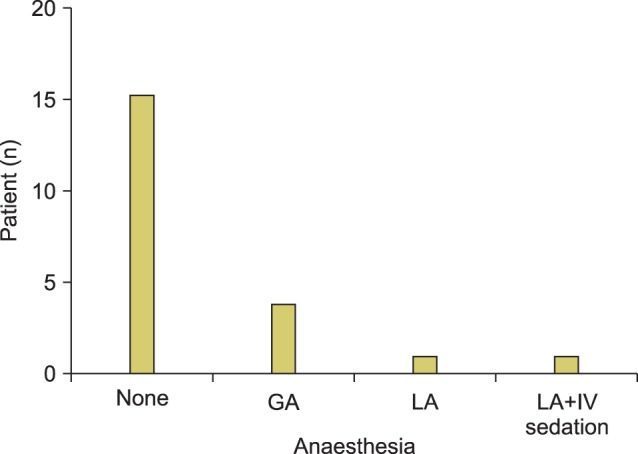

Of the 22 (84.6%) patients who received treatment (Fig. 3), manual reduction (50.0%) was the most common form of treatment used, followed by bite block traction (23.1%; Fig. 4) and surgical treatment (11.5%). Anesthesia (Fig. 5) was used in only six (27.3%) patients and consisted of local anesthesia in two (9.1%) and general anesthesia in four (18.2%) patients.

Two patients (10.0%) suffered from the complication of an anterior open bite two years after the surgical treatment, and a mobile anterior tooth was also identified in one patient (5.0%) who had been treated with bite block traction.

Go to :

TMJ dislocation has been documented in varying age groups14,24,25. In the present study, a high incidence of TMJ dislocation was noted between the third and fifth decades of life. This result was similar to other findings9,17. The peak age group incidence was 40-49 years. In contrast, other studies have reported a peak age group incidence of 20-29 years11 and 70-79 years26.

More males than females presented with TMJ dislocation, which was similar to some other findings11. However, some studies9,13 have documented a female preponderance. This difference may be related to the cultural and religious beliefs of the people in the area where this study was conducted. They are predominantly Muslims; therefore, women are more restricted in line with the Sharia legal system. As a result, some cases of TMJ dislocations may not present to the hospital for treatment, especially in female patients.

Based on the United Kingdom National Socio-economic Classification (2010), most of the patients (83.4%) whose occupational status was documented belonged to analytical class 8, and 30% of these were students. Despite this observed association between low social class and TMJ dislocation, there was no statistically significant relationship between the two variables. Previous studies did not include information regarding the social status of the patients.

The interval between the occurrence of the dislocation and the patient's presentation at the clinic ranged between 1-720 days with a mean of 51.7 days. Acute TMJ dislocations were more common (46.2%), although a higher percentage of patients presented with chronic TMJ dislocation when compared to previous findings11. Factors responsible for late presentations in our environment included cultural and religious beliefs (attributing TMJ dislocation to spiritual events), financial constraints (most of those affected were of low socio-economic class), missed diagnoses by other medical practitioners, and a shortage of skilled healthcare professionals. In some cases, patients had to travel a distance of over 300 km to seek treatment.

Similar to other studies9,11, yawning was the most common etiological factor for TMJ dislocation amongst our patients (50.0%). However, another report cited trauma as the most frequent cause13. The pathophysiology of yawning as it relates to TMJ dislocation is not fully understood. It is likely that repeated yawning (especially forceful yawning) leads to a gradual laxity of the restraining joint ligaments over time, thus predisposing such individuals to an increased range of condylar movement.

Systemic conditions such as myotonia dystrophy, Parkinson disease, multiple sclerosis, cerebral palsy, and psychiatric disorders are associated with an increased risk for TMJ dislocation26,27,28. Three of the patients in this study had known psychiatric conditions and were on antipsychotic agents. Documentation of TMJ dislocation in psychiatric patients exists in the literature and often occurs following drug-induced orofacial dystonic reactions, which commonly result from the use of anti-dopaminergic agents28,29,30,31. Dislocation may occur with any antipsychotic agent, although previous reports have implicated haloperidol, thiotixene, risperidone, and aripiprazole. One of the patients in this study was on risperidone. However, dystonic reactions may occur with other non-antipsychotic agents with antidopaminergic activity, such as antiemetics (metochlopromide).

The diagnosis of TMJ dislocation is mainly clinical; however, different imaging modalities can assist in patient assessment, treatment planning and follow-up. Plain radiography (specifically left and right oblique views of the jaws) was the only imaging modality used to assess the patients in this study because it is cheap and widely available at most centers. Trans-cranial oblique views of the TMJ, contrast computed tomography scans, i-CAT scans (Imaging Sciences International, Philadelphia, PA, USA), magnetic resonance imaging, linear and rotational plain tomograms, TMJ arthroscopy, and the Dolphin imaging system (Dolphin Imaging and Management Solutions, Chatsworth, CA, USA) are other imaging modalities that can be used in patient assessment10.

Both surgical and non-surgical methods have been used in the treatment of TMJ dislocation. Although surgical treatment is usually undertaken when conservative options have failed, no strict criteria exist in the literature for the use of any of the various conservative and surgical treatment options. Non-surgical treatment may be initiated with or without local or general anesthesia and also with or without intermaxillary fixation. Non-surgical treatment in acute TMJ dislocation involves manual reduction using the Hippocratic, wrist pivot or extra oral techniques or a combination of these techniques24. Similarly, manual reduction in acute TMJ dislocation using a bone hook has been reported32. Manual reduction was successful in 13 (59.1%) of our patients, which was a higher success rate than the 27.6%9 reported by another study. This difference in the success rate may be related to the fact that most patients in our study presented with acute dislocation, while that previous study primarily included those with chronic dislocation.

In the chronic form of TMJ dislocation, manual reduction, reduction using a Bristlow elevator or a bone hook, and bite block traction are some of the non-surgical methods available5. Bite block traction was used successfully in six (66.7%) of nine patients managed for chronic TMJ dislocation in our study. This percentage was higher than the 54.5%11 success rate reported by a previous study. Bite block traction is a good alternative for patients in whom surgery with general anesthesia carries a high risk; it is also inexpensive and prevents further deterioration of the patient's condition while waiting for a surgical slot to open up22. However, this type of traction is time consuming, can be associated with severe pain, may lead to tooth/teeth mobility, and carries a risk of wire injury to the surgeon or the patient.(Fig. 6) Non-surgical methods have also been used in the management of recurrent TMJ dislocation to prevent future dislocation, including autologous blood injection, injection of botulinum toxin A and Picibanil (Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) injection27,33.

Surgical treatment is used in both acute (in cases of superior dislocations into the middle cranial fossa) and chronic (or recurrent) TMJ dislocations and may involve endoscopic procedures or open surgery. Surgical methods range from those that create a new joint or change the axis of rotation of the TMJ (condylectomy, inverted L-shaped osteotomy, vertical subsigmoid osteotomy, or oblique subsigmoid osteotomy) to procedures that aid in the reduction of a dislocated condyle or prevent redislocation after reduction (temporalis muscle myotomy, eminectomy, Dautrey's procedure, or augmentation of the articular eminence). Three patients (13.6%) in this study received surgical treatment: an inverted L-shaped osteotomy in two patients and a vertical subsigmoid osteotomy in one patient. The low rate of surgical intervention in this study was a result of our successful treatment of the dislocation with conservative measures.

Patient compliance with postoperative follow-up review was poor and may be related to financial constraints and a feeling of being healed. However, three patients presented with complications after treatment: an anterior open bite in two of the patients managed surgically, and Ellis class I mobility of the maxillary incisors in one patient treated using bite block traction.

Go to :

In this study, male sex, middle age, yawning, and low socio-economic status appeared to be associated with TMJ dislocation; however, this observed relationship was not statistically significant. Although different treatment modalities exist in the literature, this study further highlighted the effectiveness and advantages of conservative methods of treatment.

Go to :

References

1. Last RJ. Temporomandibular joint. In : Last RJ, McMinn RMH, editors. Last's anatomy regional and applied. 9th ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone;1994. p. 523–525.

2. Osborn JW. The disc of the human temporomandibular joint: design, function and failure. J Oral Rehabil. 1985; 12:279–293. PMID: 3862791.

3. Koolstra JH. Dynamics of the human masticatory system. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2002; 13:366–376. PMID: 12191962.

4. Ingawalé S, Goswami T. Temporomandibular joint: disorders, treatments, and biomechanics. Ann Biomed Eng. 2009; 37:976–996. PMID: 19252985.

5. Caminiti MF, Weinberg S. Chronic mandibular dislocation: the role of non-surgical and surgical treatment. J Can Dent Assoc. 1998; 64:484–491. PMID: 9737079.

6. Schwartz AJ. Dislocation of the mandible: a case report. AANA J. 2000; 68:507–513. PMID: 11272957.

7. Cardoso AB, Vasconcelos BC, Oliveira DM. Comparative study of eminectomy and use of bone miniplate in the articular eminence for the treatment of recurrent temporomandibular joint dislocation. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2005; 71:32–37. PMID: 16446889.

8. Lovely FW, Copeland RA. Reduction eminoplasty for chronic recurrent luxation of the temporomandibular joint. J Can Dent Assoc. 1981; 47:179–184. PMID: 7013948.

9. Sang LK, Mulupi E, Akama MK, Muriithi JM, Macigo FG, Chindia ML. Temporomandibular joint dislocation in Nairobi. East Afr Med J. 2010; 87:32–37. PMID: 23057301.

10. Akinbami BO. Evaluation of the mechanism and principles of management of temporomandibular joint dislocation. Systematic review of literature and a proposed new classification of temporomandibular joint dislocation. Head Face Med. 2011; 7:10. PMID: 21676208.

11. Ugboko VI, Oginni FO, Ajike SO, Olasoji HO, Adebayo ET. A survey of temporomandibular joint dislocation: aetiology, demographics, risk factors and management in 96 Nigerian cases. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005; 34:499–502. PMID: 16053868.

12. Candirli C, Yüce S, Cavus UY, Akin K, Cakir B. Autologous blood injection to the temporomandibular joint: magnetic resonance imaging findings. Imaging Sci Dent. 2012; 42:13–18. PMID: 22474643.

13. Güven O. Management of chronic recurrent temporomandibular joint dislocations: a retrospective study. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2009; 37:24–29. PMID: 18996023.

14. Chhabra S, Chhabra N. Recurrent bilateral TMJ dislocation in a 20-month-old child: a rare case presentation. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2011; 29(6 Suppl 2):S104–S106. PMID: 22169834.

15. Whiteman PJ, Pradel EC. Bilateral temporomandibular joint dislocation in a 10-month-old infant after vomiting. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2000; 16:418–419. PMID: 11138886.

16. Ozcelik TB, Pektas ZO. Management of chronic unilateral temporomandibular joint dislocation with a mandibular guidance prosthesis: a clinical report. J Prosthet Dent. 2008; 99:95–100. PMID: 18262009.

17. Wahab NU, Warraich RA. Treatment of TMJ recurrent dislocation through eminectomy: a study. Pakistan Oral Dent J. 2008; 28:25–28.

18. Vasconcelos BC, Porto GG, Lima FT. Treatment of chronic mandibular dislocations using miniplates: follow-up of 8 cases and literature review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009; 38:933–936. PMID: 19467842.

19. Cascarini L, Cameron MG. Bilateral TMJ dislocation in a 23-month-old infant: a case report. Dent Update. 2009; 36:312–313. PMID: 19585855.

20. Anantharam B, Chahal N, Stephens N, Senior R. Temporo-mandibular joint dislocation: an unusual complication of transoesophageal echocardiography. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2010; 11:190–191. PMID: 19939814.

21. Sosis M, Lazar S. Jaw dislocation during general anaesthesia. Can J Anaesth. 1987; 34:407–408. PMID: 3608062.

22. Pradhan L, Jaisani MR, Sagtani A, Win A. Conservative management of chronic TMJ dislocation: an old technique revived. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2013; doi: 10.1007/s12663-013-0476-9.

23. Adekeye EO, Shamia RI, Cove P. Inverted L-shaped ramus osteotomy for prolonged bilateral dislocation of the temporomandibular joint. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1976; 41:568–577. PMID: 1063959.

24. Oliphant R, Key B, Dawson C, Chung D. Bilateral temporomandibular joint dislocation following pulmonary function testing: a case report and review of closed reduction techniques. Emerg Med J. 2008; 25:435–436. PMID: 18573960.

25. Tohyama H, Kurita H, Uehara S, Kurashina K. Retrospective analysis of clinical findings of TMJ dislocation and treatment. Shinsu Med J. 2008; 56:191–194.

26. Zanoteli E, Yamashita HK, Suzuki H, Oliveira AS, Gabbai AA. Temporomandibular joint and masticatory muscle involvement in myotonic dystrophy: a study by magnetic resonance imaging. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002; 94:262–271. PMID: 12221397.

27. Vázquez Bouso O, Forteza González G, Mommsen J, Grau VG, Rodríguez Fernández J, Mateos Micas M. Neurogenic temporomandibular joint dislocation treated with botulinum toxin: report of 4 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2010; 109:e33–e37. PMID: 20219583.

28. Zakariaei Z, Taslimi S, Tabatabaiefar MA, Arghand Dargahi M. Bilateral dislocation of temporomandibular joint induced by haloperidol following suicide attempt: a case report. Acta Med Iran. 2012; 50:213–215. PMID: 22418992.

29. Solomon S, Gupta S, Jesudasan J. Temporomandibular dislocation due to aripiprazole induced dystonia. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2010; 70:914–915. PMID: 21175449.

30. Kodama M, Fujiwara M. Risperidone-induced dislocation of the temporomandibular joint. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012; 73:176. PMID: 22401477.

31. Ibrahim ZY, Brooks EF. Neuroleptic-induced bilateral temporomandibular joint dislocation. Am J Psychiatry. 1996; 153:293–294. PMID: 8561217.

32. Kim BC, Kang Samayoa SR, Kim HJ. Reduction of superior-lateral intact mandibular condyle dislocation with bone traction hook. J Korean Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013; 39:238–241. PMID: 24471051.

33. Matsushita K, Abe T, Fujiwara T. OK-432 (Picibanil) sclerotherapy for recurrent dislocation of the temporomandibular joint in elderly edentulous patients: case reports. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007; 45:511–513. PMID: 17056162.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download