Abstract

Pain on the soft palate and pharynx can originate in several associated structures. Therefore, diagnosis of patients who complain of discomfort in these areas may be difficult and complicated. Pterygoid hamulus bursitis is a rare disease showing various symptoms in the palatal and pharyngeal regions. As such, it can be one of the reported causes of pain in these areas. Treatment of hamular bursitis is either conservative or surgical. If the etiologic factor of bursitis is osteophytic formation on the hamulus or hypertrophy of the bursa, resection of the hamulus is usually the preferred surgical treatment. We report on a case of bursitis that was managed successfully by surgical treatment and a review of the literature.

Go to :

Although comprehension of various pain syndromes and diagnostic procedures has been advanced, the diagnosis of patients who complain of discomfort in the palatal and pharyngeal regions may be difficult and complicated. The basic difficulty in diagnosis arises because neurologic, myogenic, and psychogenic pain states in the facial region have considerable overlap in terms of the manifestation of their symptoms. It has been reported that pain in the palate and pharynx can be caused by elongated styloid processes1, glossopharyngeal neuralgia2, salivary gland tumors3, myofascial pain dysfunction syndrome4, temporomandibular disorders, otitis media5, and impacted third molars.

Pterygoid hamulus bursitis can be another cause of pain in the soft palate and pharynx areas. Shankland6 proved in 1996 the histological presence of the hamular process bursae. The primary function of the bursae is to diminish the friction over the hamular process by the tendon of tensor veli palatini muscle and to make normal movement painless7. When bursitis occurs, however, movement relying on the inflamed bursae becomes painful, aggravating its inflammation and perpetuating the problem.

There are several symptoms of pterygoid hamulus bursitis as described by Shankland8: pain in the hamular region, palatal pain, ear pain, throat pain, maxillary pain, difficulty swallowing, and localized erythema. Sometimes, the patient has a clinical presentation similar to glossopharyngeal neuralgia, which makes swallowing solid food impossible9. To make an accurate diagnosis and distinguish a disease appropriately from these symptoms, a clinician needs to comprehend an associated disease thoroughly including pterygoid hamulus bursitis. Nonetheless, this is a rare disease, and only several cases have been reported.

The purpose of this article is to present a case of bursitis that was managed successfully through surgical treatment and discuss the pain associated with pterygoid hamulus bursitis with literature review.

Go to :

A 62-year-old woman who had experienced painful sensation in the oral cavity, pharynx, and ear came to Boramae Medical Center in June 2012. Other symptoms included difficulty swallowing and burning sensation of the oral cavity.

The pain was described as a pricking pain in the soft palate, causing the whole mouth and throat to be susceptible to the stimulus. The pain also radiated to the left ears. There was no history of trauma or injury. She had been undergoing treatment that involved administering antibiotics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for otic pain with stuffiness at several otorhinolaryngology clinics. When she stopped taking the drugs, however, the pain recurred. In 2011, the patient noticed swelling and painful sensation in the region of the left palate. Her doctor injected steroid in the region correspondent with the hamulus. After steroid injection, she suffered no symptoms for 1 year. In June 2012, however, the pain recurred again, so she was referred to our department.

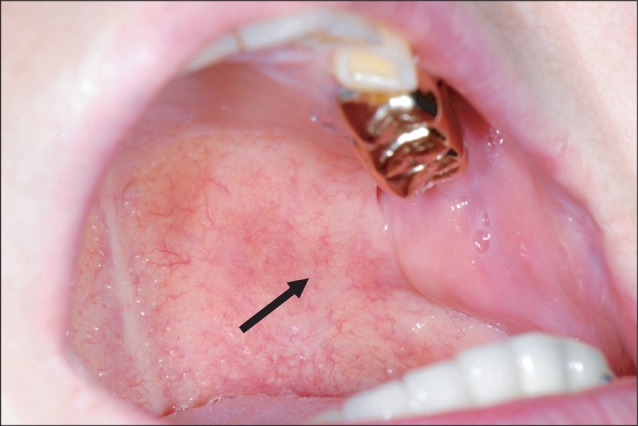

The clinical oral examination revealed a palpable mass of the left soft palate, just medial and posterior to the maxillary tuberosity. The overlying palatal mucosa was normal.(Fig. 1) On palpation, the mass under the soft palate mucosa was hard and rigid, resulting in a burning sensation of the hard and soft palate. This mass appeared to be pterygoid hamulus. According to the patient, the burning sensation had been present for 10 years, worsening when she touched the area with her tongue or finger.

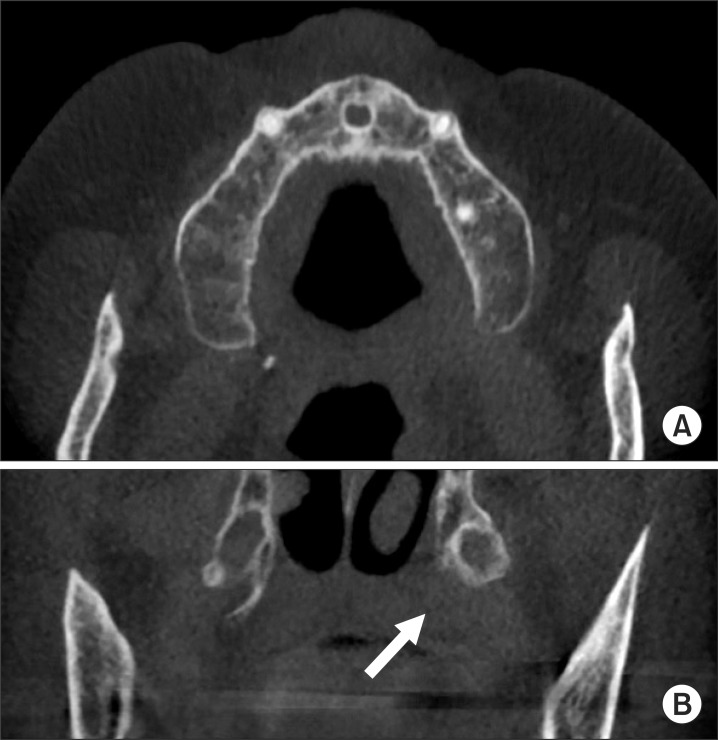

In orthopantomography, no abnormality that induced the pain of the palate was evident.(Fig. 2) The computed tomography showed that the pterygoid hamulus of the left side protruded more medially than the right side.(Fig. 3) These findings suggested that the pain was associated with mechanical stimulation to the surrounding tissues by the pterygoid hamulus, which disturbed the function of the tensor veli palatini muscle.

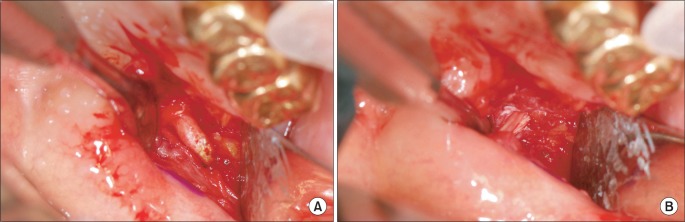

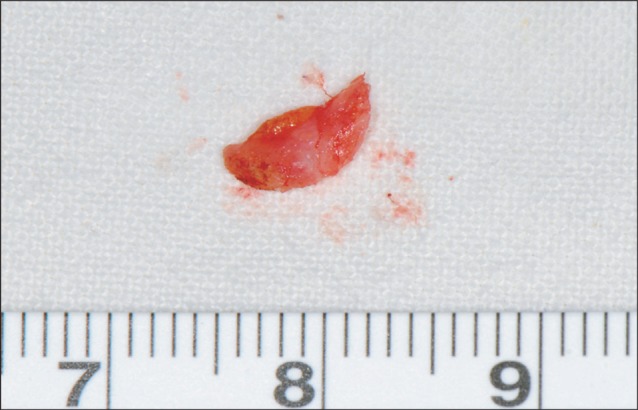

In August 2012, the left pterygoid hamulus was resected under general anesthesia. Following the incision of the overlying mucosa, surgical exposure of the pterygoid hamulus was performed using dissecting scissors. The pterygoid hamulus was removed from its base by bone rongeur.(Fig. 4) The resected specimen was 7 mm long and was sickle-shaped.(Fig. 5) The post-operative healing was uneventful (Fig. 6), and the pain radiating from the palatal region to the entire oral cavity and ear disappeared on the 5th post-operative day. During the post-operative period (8 months), the patient suffered no palatal symptoms.

Go to :

Because pain in the soft palate or in the pharyngeal region may be due to various causes, it can present a diagnostic challenge to the clinician. Although bursitis of the pterygoid hamulus is an uncommon disease, consideration of the pterygoid hamulus as a pain-inducing factor should be included in the differential diagnosis. The information gleaned from the patient's history and clinical findings may assist the clinician in reaching a more complete diagnosis. This is especially important when the clinical examination of patients reveals no positive findings.

In this case, since the major site of the pain starting from the soft palate was in the ear, she has been merely prescribed antibiotics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in the otolaryngology. She suffered a relapse of the symptoms after stopping the intake of drugs, however. It means that such condition has no potential to be neuropathic disease but is just an inflammatory disease. The absence of tenderness over the muscles of mastication and the unusual initiation and distribution of pain in this patient made the diagnosis of myofascial pain dysfunction questionable. Eyrich et al.10 reported that infiltration of local anesthesia can be an excellent diagnostic aid when differentiating hamular pain from other possible causes. Dupont and Brown11 reported a case of tenderness to palpation in the hamulus region, which was eliminated after anesthetic infiltration of the area. Shankland12 also claimed that the use of anesthetic infiltration in the hamular area may be beneficial in confirming the diagnosis of pterygoid hamular bursitis.

As far as treatment is concerned, there is no generally accepted protocol. Treatment of the pterygoid hamulus syndrome is either conservative or surgical. For palliative treatment, the local trauma origin must be eliminated, and a soft diet is suggested. Injection of synthetic cortisone into the hamulus region can be another choice of conservative treatment. Wooten et al.13 stressed that leaving the hamulus in place and educating and reassuring the patient make for adequate management. Ramirez et al.14 and Salins and Bloxham15 reported on the infiltration of synthetic cortisone in the treatment of hamular bursitis patients, obtaining satisfactory result without the recurrence of the original complaints.

In case conservative treatment is unsuccessful, or if the etiologic factor of the bursitis is an elongation of the hamulus, surgical management would be considered. Hertz16, Kronman et al.17, Eryich et al.10, and Sasaki et al.18 preferred surgical exposure and resection of the hamulus for the resolution of the patient's complaints. Shankland8 discussed three cases of the hamular bursitis treated with injection of synthetic cortisone. Among the three cases, one patient showed only a few days of relief. Surgical treatment was done, enabling the patient to be pain-free for 28 months. They commonly found a sharp prominence considered to be an elongated hamulus process associated with mechanical stimulation; the symptom of patients disappeared completely after the operation.

The pterygoid hamulus or bursa is removed, but the tendon of the tensor veli palatini is left intact if at all possible. It is best to keep the function of the tensor veli palatine muscle intact, because there is a report that pterygoid hamulotomy proved to be effective procedures for the creation of experimental serous otitis media in the cat19. Nonetheless, Noone et al.20 and Kane et al.21 concluded that the fracture of the pterygoid hamulus and consequent disturbance of the tensor veli palatini tendon do not significantly alter the state of middle ear disease.

In the presented case, the hamular area of the patient was injected with steroid, enabling the resolution of the symptoms. Note, however, that the effect of steroid injection lasted for only 1 year, and the pain in the palate and ear returned. Thus, hamulotomy was performed. The post-operative course was uncomplicated, and the patient became completely pain-free without symptoms of otitis media.

Even though there have been many attempts to explain the mechanism of pain generated from the hamular area, the precise etiology is not known. According to Kronman et al.17, the sensation of pain resulted from trauma caused by the bursitis, which inhibited muscular contraction of the tensor veli palatini muscle. In addition, the osteophyte's extension into the palatal musculature caused trauma because of the spicule's penetration of palatal soft tissues. Sasaki et al.18 suggested one possible mechanism wherein the abnormal pterygoid hamulus initially causes mechanical stimulation to the surrounding tissues and disturbance of muscular contraction of the tensor veli palatini muscle, which in turn may cause bursitis. These events may stimulate the branches of the major and minor palatini nerve, glossopharyngeal nerve, and facial nerve, which may result in painful sensation.

Under normal conditions, the normal function of the eustachian tube is to balance the pressure of the middle ear with that of the environment. The tensor veli palatini muscle dilates the eustachian tube and communicates with the nasopharynx22,23. Barsoumian et al.24 demonstrated that the fibers of the most external area of the tensor veli palatini and the fibers of the tensor tympani were joined in the middle ear in a small tendinous. In this regard, the tensor tympani and tensor veli palatini muscles act simultaneously and synergistically, being able to increase intratympanic pressure temporarily. Consequently, tensor veli palatini dysfunction in hamular bursitis can modify the intratympanic environment and show various symptoms in the ear. Ramirez et al.14 stated that the relationship between bursitis of hamulus and otic symptoms can focus on the common neural motor connections between the stomatognathic and otic system. As a result, extra-activity in the middle ear can produce consequences such as vertigo, tinnitus, otalgia, hypoacusis, and fullness.

In summary, a rare case of pterygoid hamulus bursitis was reported in this paper. The bursa of levator veli palatine muscle is present in the hamular region and can be a chronic inflammatory condition by trauma. The palatal and pharyngeal areas deserve special clinical attention especially in the differential diagnosis of a wide variety of oral and pharyngeal pains. Because the modality of treatment for bursitis is radically different from that for the other pain states in this region, the clinician should consider a probable diagnosis of bursitis.

Go to :

References

1. Ghosh LM, Dubey SP. The syndrome of elongated styloid process. Auris Nasus Larynx. 1999; 26:169–175. PMID: 10214896.

2. Love JG. Diagnosis and treatment of glossopharyngeal neuralgia. Ann Surg. 1941; 113:1078–1079. PMID: 17857808.

3. Raustia AM, Oikarinen KS, Luotonen J, Salo T, Pyhtinen J. Parotid gland carcinoma simulating signs and symptoms of craniomandibular disorders--a case report. Cranio. 1993; 11:153–156. PMID: 8495508.

4. Brooke RI, Stenn PG, Mothersill KJ. The diagnosis and conservative treatment of myofascial pain dysfunction syndrome. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1977; 44:844–852. PMID: 341019.

5. Youniss S. The relationship between craniomandibular disorders and otitis media in children. Cranio. 1991; 9:169–173. PMID: 1802427.

6. Shankland WE 2nd. Bursitis of the hamular process. Part I: anatomical and histological evidence. Cranio. 1996; 14:186–189. PMID: 9110609.

7. Putz R, Kroyer A. Functional morphology of the pterygoid hamulus. Ann Anat. 1999; 181:85–88. PMID: 10081567.

8. Shankland WE 2nd. Bursitis of the hamular process. Part II: diagnosis, treatment and report of three case studies. Cranio. 1996; 14:306–311. PMID: 9110625.

9. Gores RJ. Pain due to long hamular process in the edentulous patient. Report of two cases. J Lancet. 1964; 84:353–354. PMID: 14199335.

10. Eyrich GK, Locher MC, Warnke T, Sailer HF. The pterygoid hamulus as a pain-inducing factor. A report of a case and a radiographic study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1997; 26:275–277. PMID: 9258718.

11. Dupont JS Jr, Brown CE. Comorbidity of pterygoid hamular area pain and TMD. Cranio. 2007; 25:172–176. PMID: 17696033.

12. Shankland WE 2nd. Pterygoid hamulus bursitis: one cause of craniofacial pain. J Prosthet Dent. 1996; 75:205–210. PMID: 8667281.

13. Wooten JW, Tarsitano JJ, Reavis DK. The pterygoid hamulus: a possible source for swelling erythema, and pain: report of three cases. J Am Dent Assoc. 1970; 81:688–690. PMID: 5272119.

14. Ramirez LM, Ballesteros LE, Sandoval GP. Hamular bursitis and its possible craniofacial referred symptomatology: two case reports. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2006; 11:E329–E333. PMID: 16816817.

15. Salins PC, Bloxham GP. Bursitis: a factor in the differential diagnosis of orofacial neuralgias and myofascial pain dysfunction syndrome. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1989; 68:154–157. PMID: 2780016.

16. Hertz RS. Pain resulting from elongated pterygoid hamulus: report of case. J Oral Surg. 1968; 26:209–210. PMID: 5237185.

17. Kronman JH, Padamsee M, Norris LH. Bursitis of the tensor veli palatini muscle with an osteophyte on the pterygoid hamulus. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1991; 71:420–422. PMID: 2052325.

18. Sasaki T, Imai Y, Fujibayashi T. A case of elongated pterygoid hamulus syndrome. Oral Dis. 2001; 7:131–133. PMID: 11355439.

19. Odoi H, Proud GO, Toledo PS. Effects of pterygoid hamulotomy upon eustachian tube function. Laryngoscope. 1971; 81:1242–1244. PMID: 5569676.

20. Noone RB, Randall P, Stool SE, Hamilton R, Winchester RA. The effect on middle ear disease of fracture of the pterygoid hamulus during palatoplasty. Cleft Palate J. 1973; 10:23–33. PMID: 4509407.

21. Kane AA, Lo LJ, Yen BD, Chen YR, Noordhoff MS. The effect of hamulus fracture on the outcome of palatoplasty: a preliminary report of a prospective, alternating study. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2000; 37:506–511. PMID: 11034035.

22. Spauwen PH, Hillen B, Lommen E, Otten E. Three-dimensional computer reconstruction of the eustachian tube and paratubal muscles. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 1991; 28:217–219. PMID: 2069979.

23. Swarts JD, Rood SR. The morphometry and three-dimensional structure of the adult eustachian tube: implications for function. Cleft Palate J. 1990; 27:374–381. PMID: 2253384.

24. Barsoumian R, Kuehn DP, Moon JB, Canady JW. An anatomic study of the tensor veli palatini and dilatator tubae muscles in relation to eustachian tube and velar function. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 1998; 35:101–110. PMID: 9527306.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download