Abstract

The buccal fat pad is specialized fat tissue located anterior to the masseter muscle and deep to the buccinator muscle. Possessing a central body and four processes it provides separation allowing gliding motion between muscles, protects the neurovascular bundles from injuries, and maintains facial convexity. Because of its many advantageous functions, the use of the buccal fat pad during oral and maxillofacial procedures is promoted for the reconstruction of defects secondary to tumor resection, and those defects resulting from oroantral fistula caused by dento-alveolar surgery or trauma. We used the pedicled buccal fat pad in the reconstruction of intraoral defects such as oroantral fistula, maxillary posterior bone loss, or defects resulting from tumor resection. Epithelization of the fat tissue began 1 week after the surgery and demonstrated stable healing without complications over a long-term period. Thus, we highly recommend the use of this procedure.

Since the case report on the first oroantral fistula and oronasal fistula closing surgery using pedicled buccal fat pad combined with skin graft in 1977 by Egyedi1, surgery using buccal fat pad has been used effectively in the restoration of defects in the maxillofacial region, required esthetic and functionality. In 1983, Neder2 performed the closure of intraoral defects using free buccal fat; in 1986, Tideman et al.3 reported that the restoration of defects is possible with buccal fat pad without skin graft. Oroantral fistula is a common complication in maxillary teeth extraction or sinus lift, and primary closure is often not complete in the defect after resecting tumor in the maxillofacial area. The most common treatment of choice is the closure using the local mucoperiosteal flap or a cover of defect using acrylic resin. As reported previously, the buccal local flap needs additional vestibuloplasty because the vestibule may by lowered or the attached gingiva may be reduced. On the other hand, the palatal island flap can cause pain due to bone exposure or damage to the thickness of tissue or reduction of blood supply when rotated4. Moreover, oral closing device using acrylic resin (Obturator) is difficult to use due to insufficient suitability and various disadvantages including gagging reflex.

Anatomically, the buccal fat pad is composed of the central body and four processes-buccal, pterygoid, pterygopalatine, and temporal process. It is in the masticatory space between the masseter muscle and buccinator muscle, so it can be easily accessed by exposing in the mouth when cutting the buccinator muscle5,6 and is good for engraftment with sufficient blood supply because it receives blood from superficial temporal artery, internal maxillary artery, facial artery, and maxillary artery6-8. In the case of the oral recipient site, epithelization begins 7 days after the surgery; histologically, epithelization with surrounding tissues is completed after 4-6 weeks3,9-11. The authors reviewed literature and reported successful clinical results of closure and reconstruction of the oroantral fistula occured after extraction of the maxillary molarsmaxillary sinusitis, bone loss of the maxillary posterior caused by osteomyelitis, and defect after the tumor resection.

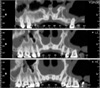

A 23-year-old male patient visited us because the extraction area of the maxillary right second premolar, extracted 3 years ago, was not closed. After examining the radiographs and conducting clinical tests, oroantral fistula was detected.(Figs. 1. A, 1. B) We performed the operation under general anesthesia, and we elevated the mucoperiosteal flap with vertical incision in the proximal area of the maxillary right first premolar and second molar respectively, then the pedicled buccal fat pad was exposed at the posterior area of the maxillary first molar, and we moved it forward.(Fig. 1. C) And primary closure was done. Stitch out was performed 1 week after the operation, and the patient was healed without bleeding or dehiscence.(Fig. 1. D) In the third week after the operation, the patient visited again, we finished treatment because the oroantral fistula was closed completely without any symptom and visible dehiscence, and air did not leak in the Valsalva maneuver.

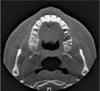

A 50-year-old male patient visited us due to exist cystic lesion and to discharge pus in the left maxillary sinus. He had received sinusitis operation a private otolaryngology clinic 30 years ago. Clinical tests revealed oroantral fistula in the maxillary left second molar area. In the computed tomography (CT) scan examination, a radiolucent lesion was identified in the left maxillary sinus.(Fig. 2) He was diagnosed with post-operative maxillary cyst and oroantral fistula, so we performed Calwell-Luc operation under general anesthesia. We incised vertically in the proximal area of the maxillary left first premolar, elevating the flap posterior, and used a sinus lateral approach. Afterward, we exposed the pedicled buccal fat pad at the posterior of the left maxillary tuberosity and closed fistula of the maxillary left second molar area.(Fig. 3) Stitch out was performed after 1 week, and the patient was healed without any limitation of mouth opening or salivation. One month after the operation, we finished treatment with the regular follow up of the patient because the symptoms disappeared.

A 29-year-old female patient referred us complaining of severe pain because the extraction socket of the maxillary left first molar teeth extracted a year and a half ago was not closed and it generated pus. Based on clinical tests and CT scan examination (Fig. 4) combined with an infection of the extraction socket, she was diagnosed with maxillary-osteomyeltis. Thus, we performed sequestrectomy of necrotic bone, extracted the maxillary left second premolar involved, and carried out primary closure of the defect area with pedicled buccal fat pad under general anesthesia.(Fig. 5. A) Stitch out was performed after 1 week, and epithelization without dehiscence was confirmed.(Fig. 5. B)

A 50-year-old female patient visited us after being referred by an otolaryngology clinic for the evaluation of raddish lesion in the left buccal area.(Fig. 6. A) The biopsy revealed mucoepidermoid carcinoma, but the positron emmision tomography (PET) CT scan showed that it did not spread to other organs including cervical lymph gland. We resected the lesion from the posterior of the maxillary left second molar area to the pterygomandibular raphe, and reconstructed the defect with exposed pedicled buccal fat pad.(Figs. 6. B, 6. C) Stitch out was performed after 1 week; though part of the grafted buccal fat pad became necrosis, the patient was healed without dehiscence and bleeding.(Fig. 6. D) Three months after the surgery, the regular follow up showed that cancer did not recur based on the magnetic resonance imaging and PET scan, and the patient had been cured steadily.

A 59-year-old male patient visited us because the left maxillary sinus area had swollen and it has been bleeding for a long time. The incisional biopsy revealed salivary duct carcinoma. We performed radical resection and partial maxillectomy including maxillary left first and second molar tooth, and closed the defect area with ipsilateral pedicled buccal fat pad.(Fig. 7. A) The size of the defect area was 5×3×3 cm. One week after the surgery, though part of it became necrosis, there was no dehiscence and bleeding.(Fig. 7. B) After 3 months, complete epithelization was verified in a regular follow up.(Fig. 7. C)

Sufficient blood supply of the buccal fat pad is deemed to increase the success rate of surgery and reduce the side effects by increasing the success rate of engraftment with the surrounding tissues after reconstruction, improving structural resistance to infection or other stimuli, and promoting fast epithelization12-14. The epithelization of the buccal fat pad used in the reconstruction started within 1 week of the reconstruction and ended within 6 weeks. The histological examination revealed no fat cell, and the buccal fat pad can reportedly maintain the role of membrane3,9-11. A side effect of closure using buccal fat pad is the recurrence of fistula due to partial necrosis and loss of flap. In most cases, it is generated when the defect area is large6,14-17. Since Egyedi1 reported that it can be used for defects smaller than 4 cm, other studies have been conducted continuously. Most authors recommend the reconstruction of defects measuring under 5×4 cm without tension when using pedicled buccal fat pad12,18, since they believe it minimizes complications including recurrence of fistula and necrosis in reconstruction of the severe defects. Our cases also showed successful treatments with complete epithelization without dehiscence for up to 5×3×3 cm.

Other complications include the infection of the restored area, loss of tissue due to necrosis or physical impact, hematoma, and bleeding. To prevent them, there is a need to perform proper disinfection and administer antibiotics as well as reduce tension using tensionless suture with the surrounding tissues to improve blood supply3,10,17. Furthermore, Amin et al.8 recommended using a cover or an oral closing device using acrylic resin (Obturator) to prevent stimulation and distortion of the operated area. In our cases, operations were performed in aseptic state and under general anesthesia, and tissues were sutured with minimizing tension. To achieve the aforesaid purposes, we exposed the pedicled buccal fat pad at the closest location and used enough amount of buccal fat pad. In addition, we administered second-generation Cephalosporin-type antibiotics for 4-7 days after the operation and performed intraoral dressing until the removal of stitches. There was no bleeding after the removal of sutures; though partial necrosis was detected, the patients were cured successfully without using any additional device.

We obtained successful results in reconstruction of the intraoral defects using pedicled buccal fat pad, which has many advantages as mentioned above. We report these cases to recommend the use of pedicled buccal fat pad because it can be utilized more widely with considering the post-surgery problems and complications.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Case 1. A. Preoperative dental panoramic X-ray. B. Intraoral view of oroantral fistula. C. Closed the oroantral fistula with buccal fat pad (size: 1×1 cm). D. One week after the operation. There was no bleeding and dehiscence. |

| Fig. 2Preoperative dental computed tomography image of case 2. Oroantral fistula was detected in the #27 area. |

| Fig. 3Case 2. Primary closure with buccal fat pad measuring 1.5×1 cm (photographed using dental mirror). |

| Fig. 4Preoperative computed tomography image of case 3 (horizontal view). Sequestrum was detected around the #25 root area. |

| Fig. 5Case 3. A. Primary closure with buccal fat pad after the extraction of #25 and sequestrectomy of that area (size: 2.5×2 cm). B. One week after the operation. |

References

1. Egyedi P. Utilization of the buccal fat pad for closure of oroantral and/or oro-nasal communications. J Maxillofac Surg. 1977. 5:241–244.

3. Tideman H, Bosanquet A, Scott J. Use of the buccal fat pad as a pedicled graft. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1986. 44:435–440.

4. Luskin IR. Reconstruction of oral defects using mucogingival pedicle flaps. Clin Tech Small Anim Pract. 2000. 15:251–259.

5. Alkan A, Dolanmaz D, Uzun E, Erdem E. The reconstruction of oral defects with buccal fat pad. Swiss Med Wkly. 2003. 133:465–470.

6. Colella G, Tartaro G, Giudice A. The buccal fat pad in oral reconstruction. Br J Plast Surg. 2004. 57:326–329.

7. Baumann A, Ewers R. Application of the buccal fat pad in oral reconstruction. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2000. 58:389–392.

8. Amin MA, Bailey BM, Swinson B, Witherow H. Use of the buccal fat pad in the reconstruction and prosthetic rehabilitation of oncological maxillary defects. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005. 43:148–154.

9. Hanazawa Y, Itoh K, Mabashi T, Sato K. Closure of oroantral communications using a pedicled buccal fat pad graft. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1995. 53:771–775.

10. Rapidis AD, Alexandridis CA, Eleftheriadis E, Angelopoulos AP. The use of the buccal fat pad for reconstruction of oral defects: review of the literature and report of 15 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2000. 58:158–163.

11. Samman N, Cheung LK, Tideman H. The buccal fat pad in oral reconstruction. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1993. 22:2–6.

12. Singh J, Prasad K, Lalitha RM, Ranganath K. Buccal pad of fat and its applications in oral and maxillofacial surgery: a review of published literature (February) 2004 to (July) 2009. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2010. 110:698–705.

13. Stuzin JM, Wagstrom L, Kawamoto HK, Baker TJ, Wolfe SA. The anatomy and clinical applications of the buccal fat pad. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990. 85:29–37.

14. Zhang HM, Yan YP, Qi KM, Wang JQ, Liu ZF. Anatomical structure of the buccal fat pad and its clinical adaptations. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002. 109:2509–2518.

15. Hao SP. Reconstruction of oral defects with the pedicled buccal fat pad flap. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000. 122:863–867.

16. Poeschl PW, Baumann A, Russmueller G, Poeschl E, Klug C, Ewers R. Closure of oroantral communications with Bichat's buccal fat pad. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009. 67:1460–1466.

17. Fujimura N, Nagura H, Enomoto S. Grafting of the buccal fat pad into palatal defects. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1990. 18:219–222.

18. Kim ES. Clinical evaluation of the effectiveness of pedicled buccal fat pad grafts in closure of oroantral communications. J Korean Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2000. 26:297–300.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download