INTRODUCTION

The incidence of colorectal cancer is rapidly increasing, making it an important disease in Korea [

1]. The National Cancer Screening Program (NCSP) was implemented in 2002 for stomach, breast, and cervical cancer screening. In 2004, colorectal cancer screening using fecal immunochemical tests (FITs) was introduced. FITs measure the concentration of hemoglobin in feces qualitatively or quantitatively [

2], and are simple, noninvasive, and inexpensive tests, widely used as an organized population screening method. FITs have been shown to generate fewer false-positive results than guaiac fecal occult blood tests or an alternative test [

3].

Although the participation rate for colorectal cancer screening has rapidly increased with the number of cancer screening facilities, issues with the quality assurance of these facilities have been noted [

4]. Since 2008, Korean Society of Laboratory Medicine (KSLM), Korean Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (KSGE), and the National Cancer Center of Korea have implemented the National Quality Improvement Program for colorectal cancer screening to evaluate facilities participating in the NCSP, with the goal of improving the quality of colorectal cancer screening [

5678].

Annually, approximately 3.8 million FITs are performed as a part of the NCSP. Of these, examinees with positive FITs undergo additional colonoscopies, with subsequent polypectomies or biopsies if a lesion or polyp found during initial colonoscopy appears suspicious for colorectal cancer [

49]. Although false-positive results are often observed in FITs, they could be minimized with quality assurance efforts, and the unnecessary implementation of further tests could be reduced. Consequently, medical costs could be reduced.

The standardization of clinical laboratories should be considered in terms of laboratory practices (including laboratory procedures, policies, and personnel) and laboratory methods (commercial products). A recent report has indicated that the accreditation of clinical laboratories improved the accuracy of the laboratory results [

10].

This study aimed to estimate the impact of false-positive results from the NCSP screening facilities with and without participation in the quality assessment program on the health insurance budget.

Go to :

RESULTS

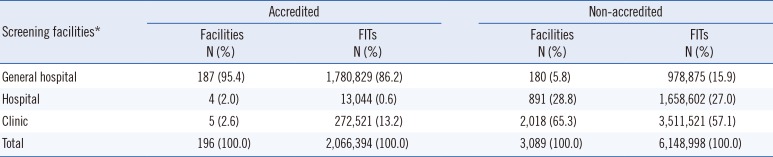

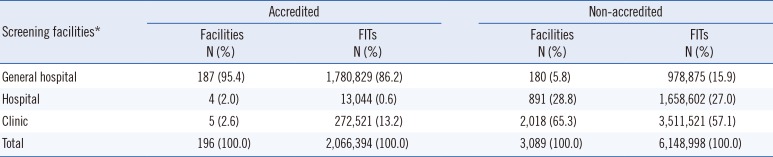

A total of 3,285 screening facilities participated in the NCSP between 2007 and 2010. Of these, 196 facilities were accredited by the KLAP. These facilities were mostly (95.4%) general hospitals. There were only five accredited clinics, and these included 272,521 examinees (representing 13.2% of the total number of FITs) (

Table 1).

Table 1

Number of screening facilities and examinees in the National Cancer Screening Program for colorectal cancer between 2007 and 2010 according to accreditation by the Korean Laboratory Accreditation Program

|

Screening facilities*

|

Accredited |

Non-accredited |

|

Facilities N (%) |

FITs N (%) |

Facilities N (%) |

FITs N (%) |

|

General hospital |

187 (95.4) |

1,780,829 (86.2) |

180 (5.8) |

978,875 (15.9) |

|

Hospital |

4 (2.0) |

13,044 (0.6) |

891 (28.8) |

1,658,602 (27.0) |

|

Clinic |

5 (2.6) |

272,521 (13.2) |

2,018 (65.3) |

3,511,521 (57.1) |

|

Total |

196 (100.0) |

2,066,394 (100.0) |

3,089 (100.0) |

6,148,998 (100.0) |

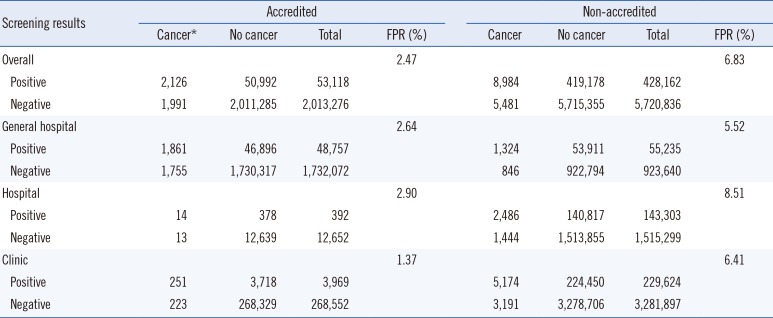

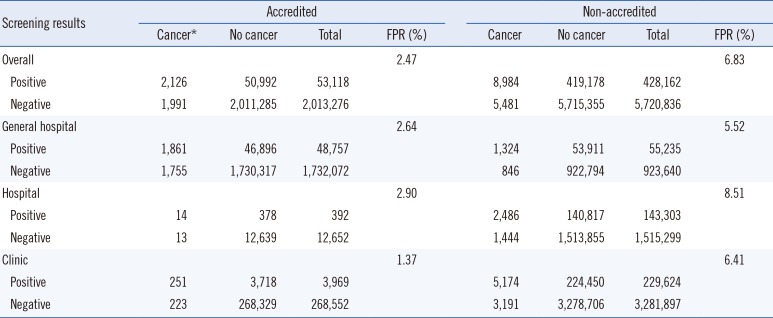

Conversely, most of the non-accredited screening facilities were clinics, and the number of facilities and FITs were 2,018 and 3,511,521, respectively. The false-positive rate for all the accredited screening facilities was 2.47%, which was lower than that for non-accredited facilities (6.83%). The false-positive rates for accredited general hospitals, hospitals, and clinics were 2.64%, 2.90%, and 1.37%, respectively, and those for non-accredited screening facilities were 5.52%, 8.51%, and 6.41%, respectively (

Table 2).

Table 2

Outcomes of the National Cancer Screening Program for colorectal cancer between 2007 and 2010 according to accreditation by the Korean Laboratory Accreditation Program

|

Screening results |

Accredited |

Non-accredited |

|

Cancer*

|

No cancer |

Total |

FPR (%) |

Cancer |

No cancer |

Total |

FPR (%) |

|

Overall |

|

|

|

2.47 |

|

|

|

6.83 |

|

Positive |

2,126 |

50,992 |

53,118 |

8,984 |

419,178 |

428,162 |

|

Negative |

1,991 |

2,011,285 |

2,013,276 |

5,481 |

5,715,355 |

5,720,836 |

|

General hospital |

|

|

|

2.64 |

|

|

|

5.52 |

|

Positive |

1,861 |

46,896 |

48,757 |

1,324 |

53,911 |

55,235 |

|

Negative |

1,755 |

1,730,317 |

1,732,072 |

846 |

922,794 |

923,640 |

|

Hospital |

|

|

|

2.90 |

|

|

|

8.51 |

|

Positive |

14 |

378 |

392 |

2,486 |

140,817 |

143,303 |

|

Negative |

13 |

12,639 |

12,652 |

1,444 |

1,513,855 |

1,515,299 |

|

Clinic |

|

|

|

1.37 |

|

|

|

6.41 |

|

Positive |

251 |

3,718 |

3,969 |

5,174 |

224,450 |

229,624 |

|

Negative |

223 |

268,329 |

268,552 |

3,191 |

3,278,706 |

3,281,897 |

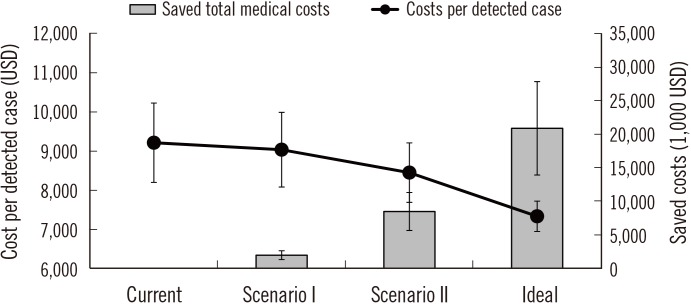

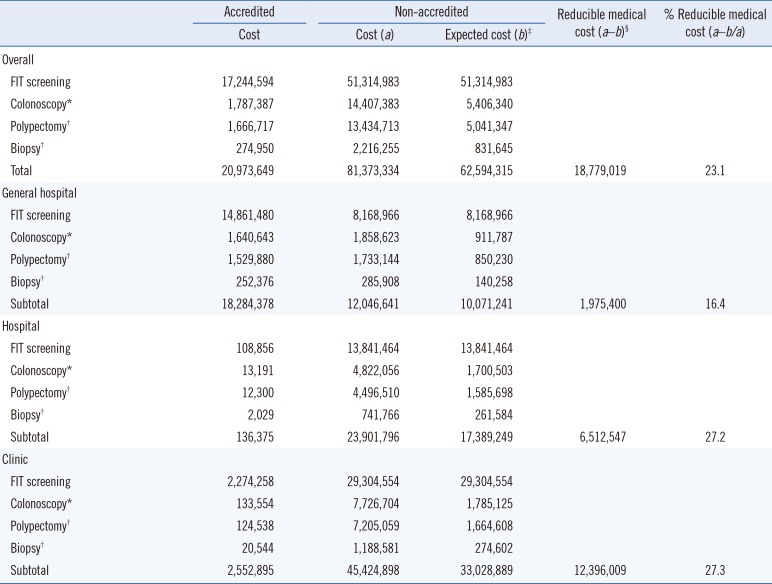

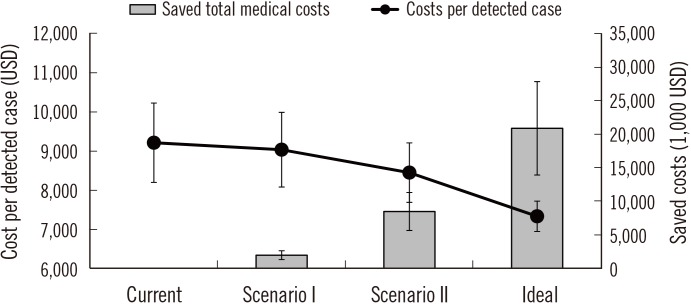

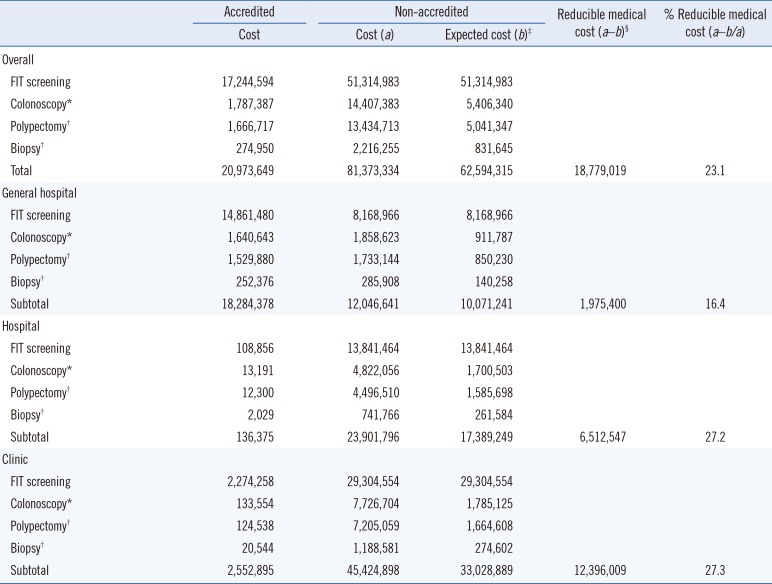

Non-accredited facilities incurred costs of 81,373,334 US dollars (USD) for FIT expenses and additional tests; however, if the false-positive rate decreased to that of accredited facilities, these costs would decline to approximately 62,594,315 USD, resulting in a financial reduction effect of approximately 18,779,019 USD (

Table 3). In the current status of accreditation, the cost of detecting a single case of colorectal cancer is approximately 9,212 USD; however, accreditation of all screening facilities would reduce the cost to approximately 7,332 USD. The greatest financial reduction effect would be achieved with accreditation of all the clinics (

Fig. 1).

| Fig. 1

Changes in the reduction in medical costs according to the proportion of facilities accredited by the Korean Laboratory Accreditation Program (KLAP). The error bars on the gray bars and black circles represent the colonoscopy performed assuming 40% and 80% sensitivity, respectively.

Current, Maintenance of the proportion of KLAP-accredited facilities; Scenario I, Assumption of accreditation of all general hospitals by the KLAP; Scenario II, Assumption of accreditation of all general hospitals and hospitals by the KLAP; Ideal, Assumption of accreditation of all screening facilities by the KLAP.

|

Table 3

Estimated costs of the National Cancer Screening Program for colorectal cancer according to accreditation by the Korean Laboratory Accreditation Program

|

Accredited |

Non-accredited |

Reducible medical cost (a–b)§

|

% Reducible medical cost (a–b/a) |

|

Cost |

Cost (a) |

Expected cost (b)‡

|

|

Overall |

|

|

|

|

|

|

FIT screening |

17,244,594 |

51,314,983 |

51,314,983 |

|

|

|

Colonoscopy*

|

1,787,387 |

14,407,383 |

5,406,340 |

|

|

|

Polypectomy†

|

1,666,717 |

13,434,713 |

5,041,347 |

|

|

|

Biopsy†

|

274,950 |

2,216,255 |

831,645 |

|

|

|

Total |

20,973,649 |

81,373,334 |

62,594,315 |

18,779,019 |

23.1 |

|

General hospital |

|

|

|

|

|

|

FIT screening |

14,861,480 |

8,168,966 |

8,168,966 |

|

|

|

Colonoscopy*

|

1,640,643 |

1,858,623 |

911,787 |

|

|

|

Polypectomy†

|

1,529,880 |

1,733,144 |

850,230 |

|

|

|

Biopsy†

|

252,376 |

285,908 |

140,258 |

|

|

|

Subtotal |

18,284,378 |

12,046,641 |

10,071,241 |

1,975,400 |

16.4 |

|

Hospital |

|

|

|

|

|

|

FIT screening |

108,856 |

13,841,464 |

13,841,464 |

|

|

|

Colonoscopy*

|

13,191 |

4,822,056 |

1,700,503 |

|

|

|

Polypectomy†

|

12,300 |

4,496,510 |

1,585,698 |

|

|

|

Biopsy†

|

2,029 |

741,766 |

261,584 |

|

|

|

Subtotal |

136,375 |

23,901,796 |

17,389,249 |

6,512,547 |

27.2 |

|

Clinic |

|

|

|

|

|

|

FIT screening |

2,274,258 |

29,304,554 |

29,304,554 |

|

|

|

Colonoscopy*

|

133,554 |

7,726,704 |

1,785,125 |

|

|

|

Polypectomy†

|

124,538 |

7,205,059 |

1,664,608 |

|

|

|

Biopsy†

|

20,544 |

1,188,581 |

274,602 |

|

|

|

Subtotal |

2,552,895 |

45,424,898 |

33,028,889 |

12,396,009 |

27.3 |

Go to :

DISCUSSION

The false-positive rates of the FIT screening facilities participating in the NCSP differed according to the accreditation of the quality assessment program. Accredited screening facilities had remarkably lower false-positive rates than those of the non-accredited facilities. These differences were clearly shown to be associated with the type of screening facility. If the false-positive rates of non-accredited screening facilities decreased to that of accredited facilities, then colorectal cancer could be detected more efficiently, reducing insurance costs associated with the colorectal cancer NCSP. Notably, this budget-saving effect was most apparent to clinics.

According to the World Health Organization, accreditation is the most commonly used external mechanism to improve standard-based quality in the medical field [

14]. The KLAP is a quality assurance system for clinical laboratories in Korea and is designed to assess a comprehensive quality standard checklist related to the practices of clinical laboratories through peer review. The KLAP checklist is designed to determine and manage the structure, process, and outcome of the laboratory practice, and to continually identify focus areas and encourage activities for improvement. This process appears to improve the quality of laboratory practice by enhancing the confidence and ability of laboratory workers [

5].

Only 6% of the facilities participating in the NCSP for colorectal cancer screening were accredited by the KLAP; these facilities were primarily general hospitals. The five accredited clinics were institutions offering comprehensive health checkups and performing approximately 272,000 FITs. There were 2,018 (65.3%) non-accredited clinics, performing approximately 3,511,000 (57.1%) FITs. Of these non-accredited screening facilities, over 600 facilities examined fewer than 100 FITs annually. Screening facilities with lower hospital volume have a lower awareness of and willingness to participate in external quality control of their clinical laboratories, due to the financial burden involved. Since 2007, KSLM has conducted an external quality assessment of FITs, using external quality assessment materials. A total of 650 general hospitals and hospitals participated in the external quality assessment of KSLM between 2007 and 2009, and the number of participating facilities has not increased [

67].

If all facilities participating in the NCSP for colorectal cancer could maintain the false-positive rates of accredited facilities, this would result in financial savings of approximately 19 million USD, with the largest effects observed in clinics and the smallest effects observed in general hospitals (clinics, 12,396,009 USD; hospitals, 6,512,547 USD; and general hospitals, 1,975,400 USD). However, there are 2,018 clinics requiring additional accreditation, compared with only 180 general hospitals and 891 hospitals. The financial reduction effect per additional accredited facility was the largest for general hospitals and the smallest for clinics (general hospitals, 10,974 USD; hospitals, 7,309 USD; and clinics, 6,143 USD).

In contrast to the considerable interest generated by quality assurance for invasive screening tests, such as colonoscopy, the importance of quality assurance for FITs has not yet been extensively studied [

815]. However, in the NCSP, if the FIT result is positive, additional colonoscopy tests are recommended [

16]. Therefore, appropriate assessment of quality assurance based on FITs may minimize unnecessary colonoscopies. Once the accuracy of FIT screening is improved and the harm from screening is minimized, the NCSP will be more effective and efficient [

1718].

The screening interval for colorectal cancer based on the NCSP was changed from two years to one year in 2012, and continuous efforts to increase the participation rates will increase the number of FIT examinees [

4]. If four million FITs are implemented annually as a part of the NCSP, the health insurance budget related to the NCSP for colorectal cancer can save 10,168,208 USD each year by quality control efforts. However, it is not easy to implement a quality assessment program for all the screening facilities participating in the NCSP; therefore, general hospitals and hospitals are preferentially encouraged to participate in the quality assessment programs. Internal and external quality assessment programs for clinics need to be developed to provide high-quality colorectal cancer screening. Furthermore, strategies to increase the hospital volume of clinics participating in the NCSP should also be developed.

This study had several limitations. First, assessment items included in the KLAP did not include items related to FITs. The presence of accreditation in the KLAP did not directly reflect the reliability of the FIT process. This may explain the reason for lower false-positivity of accredited laboratories than that of non-accredited ones. However, KLAP accreditation could be used as an indicator of the overall status of a laboratory. Second, we did not consider different FIT cut-off levels according to equipment and test reagents from different manufacturers. Third, the range of the health insurance budget was restricted to the cost of screening and diagnosis and did not include any other medical expenses, such as treatment or out-of-pocket costs. Finally, we did not consider the effects of false-negative results on the budget. Although the impact on the budget was considered, we could not distinguish between preventable (missing interval cancers) and unavoidable cases (true interval cancers).

In conclusion, participation of laboratories in a quality assessment program could reduce false-positive rates and minimize the requirement of unnecessary tests, thereby increasing the cost-effectiveness of colorectal cancer screening programs. Strategies to encourage screening facilities to participate in quality assessment programs should be developed. Moreover, efforts to develop quality assessment programs according to hospital type are required to improve the quality of cancer screening services.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download