Abstract

Diagnosis of the urea cycle disorder (USD) carbamoyl-phosphate synthetase 1 (CPS1) deficiency (CPS1D) based on only the measurements of biochemical intermediary metabolites is not sufficient to properly exclude other UCDs with similar symptoms. We report the first Korean CPS1D patient using whole exome sequencing (WES). A four-day-old female neonate presented with respiratory failure due to severe metabolic encephalopathy with hyperammonemia (1,690 µmol/L; reference range, 11.2-48.2 µmol/L). Plasma amino acid analysis revealed markedly elevated levels of alanine (2,923 µmol/L; reference range, 131-710 µmol/L) and glutamine (5,777 µmol/L; reference range, 376-709 µmol/L), whereas that of citrulline was decreased (2 µmol/L; reference range, 10-45 µmol/L). WES revealed compound heterozygous pathogenic variants in the CPS1 gene: one novel nonsense pathogenic variant of c.580C>T (p.Gln194*) and one known pathogenic frameshift pathogenic variant of c.1547delG (p.Gly516Alafs*5), which was previously reported in Japanese patients with CPS1D. We successfully applied WES to molecularly diagnose the first Korean patient with CPS1D in a clinical setting. This result supports the clinical applicability of WES for cost-effective molecular diagnosis of UCDs.

Go to :

Carbamoyl-phosphate synthetase 1 (CPS1) deficiency (CPS1D; MIM #237300) is a rare autosomal recessive inborn error of the urea cycle [1]. The urea cycle is the only pathway capable of metabolizing excess nitrogen, and defective enzymes involved in the transfer of nitrogen from ammonia to urea lead to toxic hyperammonemia, a metabolic disorder with high morbidity and mortality [2]. The urea cycle consists of six enzymes: CPS1, N-acetylglutamate synthase (NAGS), ornithine carbamoyltransferase (OTC), argininosuccinate synthetase, argininosuccinate lyase, and arginase. Urea cycle disorders (UCDs) result from an inherited deficiency caused by pathogenic variations in one or more of the genes encoding the necessary enzymes [2]. With the aid of the allosteric activator N-acetylglutamate, synthesized by NAGS, CPS1 catalyzes the first step in the urea cycle, converting ammonia to carbamoyl phosphate [3]. Although UCD diagnosis is primarily based on the biochemical measurement of intermediary metabolites, such measurements cannot be used to distinguish between NAGS deficiency and CPS1D; genetic pathogenic variant testing is needed to distinguish these conditions [4].

CPS1 is a large gene located on 2q35, spanning >120 kb, encompassing 4,500 coding nucleotides over 38 coding exons [13]. More than 240 CPS1 pathogenic variations have been reported to be widely distributed among the coding exons in CPS1 pathogenic variants as described in the Leiden Open Variation Database (LOVD, http://www.LOVD.nl/CPS1) and the Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD, http://www.hgmd.org/). Only about 10% of the reported pathogenic variants occur in unrelated individuals, predominantly affecting CpG dinucleotides, further complicating diagnosis because of the "private" nature of such pathogenic variants [1]. Furthermore, individual molecular analysis of the six causative genes of UCDs for differential diagnosis is time consuming and expensive. With the recent introduction of next-generation sequencing (NGS) technology, large amounts of data can be generated at a lower cost, offering new possibilities for UCD screening and diagnosis [4]. However, to our knowledge, no CPS1D patient has yet been newly diagnosed by whole exome sequencing (WES) in a real clinical setting. Here, we report the first successful use of WES for CPS1D diagnosis.

We report a four-day-old female neonate who was referred to our institution owing to hypothermia, poor feeding, lethargy, and respiratory depression that started three days after birth. She was the first baby born at term to non-consanguineous Korean parents; her weight at birth was 2,700 g. The patient had no facial dysmorphism or other phenotypic abnormalities at birth. At admission, no physiological neurologic reflex was observed.

Her blood tests revealed hyperammonemia of 1,690 µmol/L (reference range, 11.2-48.2 µmol/L) and lactic acidosis (6.86 mmol/L; reference range, 0.2-2.2 mmol/L) with pH 7.266. Newborn screening tests for amino acid and acylcarnitine using tandem mass spectrometry showed markedly elevated levels of alanine, glutamate, and proline; however, citrulline and arginine levels were not increased. Collectively, those results suggested a UCD. Plasma amino acid analysis revealed markedly elevated alanine (2,923 µmol/L; reference range, 131-710 µmol/L) and glutamine (5,777 µmol/L; reference range, 376-709 µmol/L), decreased citrulline (2 µmol/L; reference range, 10-45 µmol/L), and arginine in the reference range. Orotic acid and uracil in urine were within the reference ranges, suggesting a UCD such as CPS1D or NAGS deficiency.

Emergency treatment involved mechanical ventilation for her respiratory failure and cardio-pulmonary resuscitation upon cardiac arrest. Intermittent episodes of seizures with lip smacking and rigidity of the extremities were noted and managed with phenobarbital and midazolam. Severe diffuse brain edema with abnormal parenchymal echogenicity including deep gray matter, suggestive of metabolic disease, was identified through a brain ultrasound. Hepatomegaly, severe gallbladder wall edema, periportal edema associated with ascites, and edematous changes along the mesentery and subcutaneous fat layers were also observed through abdominal ultrasound. Continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) was performed for rapid removal of toxic ammonia causing metabolic encephalopathy and for management of electrolytes, acid-base state, and dehydration or fluid overload. Multiple sessions of CRRT were necessary to control hyperammonemia. At 11 days after birth, phenylbutyrate and benzoate sodium (500 mg/kg/day, p.o.) was initiated with restriction of protein intake. Plasma ammonia was decreased to and maintained at <50 µmol/L after five weeks of treatment. Her electroencephalogram suggested severe diffuse cerebral dysfunction, and extensive cystic encephalomalacia with ventriculomegaly was identified through a follow-up brain ultrasound after six weeks of treatment, despite the interventions. The patient was alive through a six-month follow-up period with maintenance therapy and arginine supplements.

WES was performed as previously described [5]. Briefly, exonic sequences were enriched in the DNA sample using a SureSelect Target Enrichment kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Sequences were determined by a HiSeq2000 instrument (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA), and 150-200 bp were read paired-end. The patient's variants that passed the quality filters were screened against the public databases listed in the Standards and Guidelines for the Interpretation of Sequence Variants by the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) [6] for a global minor allele frequency <1.0%. Protein-altering variants were then selected. The variants derived from the variant filtering strategy were then prioritized on the basis of their likelihood to affect protein function by using public algorithms such as SIFT and to totally or partially match the patient's phenotype. Nucleotides are numbered from the first adenine of the ATG translation initiation codon in the CPS1 cDNA reference sequence NM_001122633.2. The variants identified in the proband were classified according to the Standards and Guidelines for the Interpretation of Sequence Variants by the ACMG [6].

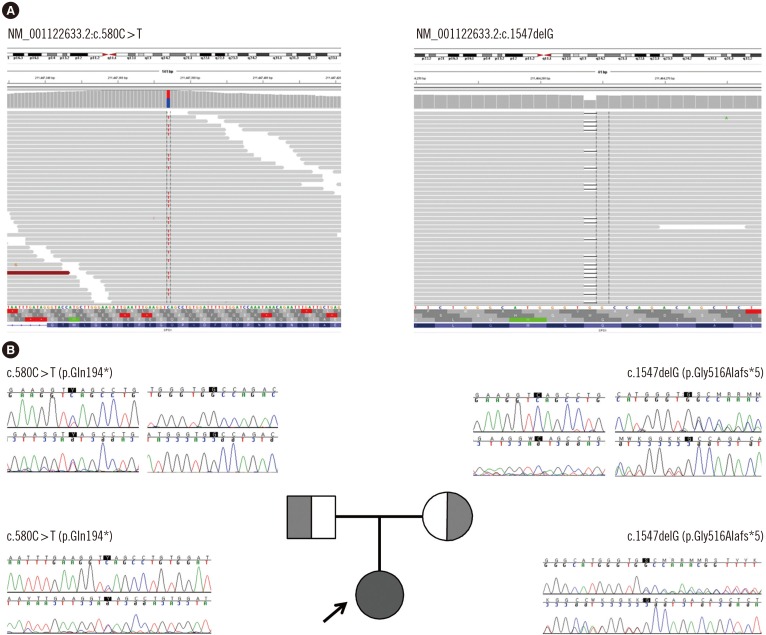

WES of the proband revealed two heterozygous variants of the CPS1 gene: one novel nonsense pathogenic variant of c.580C>T (p.Gln194*) and one previously known pathogenic frameshift pathogenic variant of c.1547delG (p.Gly516Alafs*5), which has been recurrently reported in Japanese patients with CPS1D [178]. These pathogenic variants were confirmed with Sanger sequencing (Fig. 1). A familial study was performed with targeted pathogenic variant analysis of the two CPS1 variants. The patient's mother was a heterozygous carrier of c.1547delG, while the patient's father was a heterozygous carrier of c.580C>T.

In the present study, we report a female neonate with CPS1D identified as having a novel pathogenic nonsense pathogenic variant, c.580C>T (p.Gln194*), on CPS1 exon 6. The codon change resulting in early termination occurred at the N-terminal of the CPS1 gene [3]. Different types of pathogenic variants including missense changes (~59%), deletions (~13%), small insertions or duplications (~6%), indels (~2%), nonsense (~7%), gross deletions, and splicing pathogenic variants (~13%) have been reported to be distributed across all exons of this gene, except exon 6 [1]. The pathogenic variant identified in this patient, c.1547delG (p.Gly516Alafs*5) on exon 14, has been commonly reported in the Japanese population, suggesting the possibility of an ethnic origin and a possible founder pathogenic variant among Korean and Japanese populations.

To our knowledge, this is the first case of CPS1D diagnosed by WES, which was successfully applied to identify the pathogenic variants of the disease. Although NGS technologies have been demonstrated to be clinically applicable for the molecular diagnosis of various UCDs [4], no case of newly diagnosed CPS1D by WES has been reported. This could be due to the fatal nature of CPS1D, which makes diagnosis difficult. The estimated incidence of the UCDs varies between 1:56,500 for OTC deficiency, <1:2,000,000 for NAGS deficiency, and 1:1,300,000 for CPS1D [9]; however, this is most likely an underestimation since many of the patients die unreported, undiagnosed, or both, with disease detection varying with the degree of awareness of the clinician and access to testing, diagnostics, and life-support facilities [1]. Estimating the prevalence and incidence of CPS1D in the Korean population is even more difficult because, as far as we know, this is the first reported case of CPS1D in Korea. The present study suggests the applicability of WES for the molecular diagnosis of UCDs.

Molecular diagnosis of CPS1D can be hampered by the large size of the CPS1 gene [1]. Genetic analysis is a key element in diagnosing CPS1D and for performing counseling, prenatal diagnosis, and eventually, for future procedures of disease-free embryo selection [1]. Specifically, because NAGS deficiency and CPS1D have identical clinical manifestations and a similar biochemical intermediary metabolic profile, the importance of molecular diagnosis is reinforced [2]. Despite the fact that prenatal CPS1D diagnosis has been introduced in other populations [1011], there is currently no prenatal diagnosis test in Korea. With the development of NGS, it is now possible to generate large amounts of sequence data at a lower cost and with less effort, offering new possibilities for diagnostic pathogenic variant screening [4]. A recent study on the genetic diagnosis of structural fetal abnormalities revealed by ultrasound reported the possibility of applying WES to fetuses [12]. In such cases, the step-wise approach of Sanger sequencing of individual genes can be time-consuming; WES could be a cost effective approach [513]. The present study highlights the potential for expanding the applicability of WES to the molecular diagnosis of UCDs.

In conclusion, we report the first CPS1 pathogenic variant identified by WES with a novel pathogenic variant, c.580C>T, on exon 6. This diagnostic approach was successful for diagnosing CPS1D in a real clinical setting.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the Korea Health Technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (A120030).

Go to :

Notes

Authors' Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest: No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Go to :

References

1. Häberle J, Shchelochkov OA, Wang J, Katsonis P, Hall L, Reiss S, et al. Molecular defects in human carbamoy phosphate synthetase I: mutational spectrum, diagnostic and protein structure considerations. Hum Mutat. 2011; 32:579–589. PMID: 21120950.

2. Ah Mew N, Lanpher BC, et al. Urea cycle disorders overview. In : Pagon RA, Adam MP, editors. GeneReviews(R). Seattle, WA: University of Washington;2011.

3. Díez-Fernández C, Hu L, Cervera J, Häberle J, Rubio V. Understanding carbamoyl phosphate synthetase (CPS1) deficiency by using the recombinantly purified human enzyme: effects of CPS1 mutations that concentrate in a central domain of unknown function. Mol Genet Metab. 2014; 112:123–132. PMID: 24813853.

4. Amstutz U, Andrey-Zürcher G, Suciu D, Jaggi R, Häberle J, Largiadèr CR. Sequence capture and next-generation resequencing of multiple tagged nucleic acid samples for mutation screening of urea cycle disorders. Clin Chem. 2011; 57:102–111. PMID: 21068339.

5. Choi R, Woo HI, Choe BH, Park S, Yoon Y, Ki CS, et al. Application of whole exome sequencing to a rare inherited metabolic disease with neurological and gastrointestinal manifestations: a congenital disorder of glycosylation mimicking glycogen storage disease. Clin Chim Acta. 2015; 444:50–53. PMID: 25681648.

6. Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015; 17:405–424. PMID: 25741868.

7. Wakutani Y, Nakayasu H, Takeshima T, Adachi M, Kawataki M, Kihira K, et al. Mutational analysis of carbamoylphosphate synthetase I deficiency in three Japanese patients. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2004; 27:787–788. PMID: 15617192.

8. Kurokawa K, Yorifuji T, Kawai M, Momoi T, Nagasaka H, Takayanagi M, et al. Molecular and clinical analyses of Japanese patients with carbamoylphosphate synthetase 1 (CPS1) deficiency. J Hum Genet. 2007; 52:349–354. PMID: 17310273.

9. Summar ML, Koelker S, Freedenberg D, Le Mons C, Haberle J, Lee HS, et al. The incidence of urea cycle disorders. Mol Genet Metab. 2013; 110:179–180. PMID: 23972786.

10. Finckh U, Kohlschütter A, Schäfer H, Sperhake K, Colombo JP, Gal A. Prenatal diagnosis of carbamoyl phosphate synthetase I deficiency by identification of a missense mutation in CPS1. Hum Mutat. 1998; 12:206–211. PMID: 9711878.

11. Aoshima T, Kajita M, Sekido Y, Mimura S, Itakura A, Yasuda I, et al. Carbamoyl phosphate synthetase I deficiency: molecular genetic findings and prenatal diagnosis. Prenat Diagn. 2001; 21:634–637. PMID: 11536261.

12. Carss KJ, Hillman SC, Parthiban V, McMullan DJ, Maher ER, Kilby MD, et al. Exome sequencing improves genetic diagnosis of structural fetal abnormalities revealed by ultrasound. Hum Mol Genet. 2014; 23:3269–3277. PMID: 24476948.

13. Biesecker LG, Green RC. Diagnostic clinical genome and exome sequencing. N Engl J Med. 2014; 370:2418–2425. PMID: 24941179.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download