Abstract

Background

Carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae (CRKP) is considered a serious global threat. However, little is known regarding the multidrug resistance (MDR) mechanisms of CRKP. This study investigated the phenotypes and MDR mechanisms of CRKP and identified their clonal characteristics.

Methods

PCR and sequencing were utilized to identify antibiotic resistance determinants. Integron gene cassette arrays were determined by restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis. Multi-locus sequence typing (MLST) and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) were used for epidemiological analysis. Plasmids were typed by using a PCR-based replicon typing and analyzed by conjugation and transformation assays.

Results

Seventy-eight strains were identified as resistant to at least one carbapenem; these CRKP strains had a high prevalence rate (38.5%, 30/78) of carbapenemase producers. Additionally, most isolates harbored MDR genes, including Extended spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs), AmpC, and quinolone and aminoglycoside resistance genes. Loss of porin genes was observed, and Class 1 integron was detected in 66.7% of the investigated isolates. PFGE and MLST results excluded the occurrence of clonal dissemination among these isolates.

Conclusions

A high prevalence of NDM-1 genes encoding carbapenem resistance determinants was demonstrated among the K. pneumoniae isolates. Importantly, this is the first report of blaNDM-1 carriage in a K. pneumoniae ST1383 clone in China and of a MDR CRKP isolate co-harboring blaNDM-1, blaKPC-2, blaCTX-M, blaSHV, acc(6′)-Ib, rmtB, qnrB, and acc(6′)-Ib-cr.

Klebsiella pneumoniae, a gram-negative bacillus, causes a wide array of infections resulting in severe morbidity and mortality. Isolates of this species have been reported to be resistant to almost all classes of antibiotics through progressive mutations in chromosomally encoded genes and acquisition of genes from mobile plasmids and integrons [1]. Carbapenems, widely used for the treatment of serious infections, are effective against K. pneumoniae, especially multidrug resistant (MDR) Enterobacteria producing high levels of AmpC cephalosporinases or extended spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs). However, in recent years, widespread use of carbapenem has accelerated the growth of resistant strains in different regions [12]. The global spread of carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae (CRKP) has become a serious clinical challenge because of the limited treatment options.

The mechanisms underlying carbapenem resistance in K. pneumoniae species generally involve the production of carbapenemase and the loss or decreased expression of outer membrane proteins. Additionally, the production of AmpC and ESBL plays an important role in these resistance mechanisms [3]. KPC and NDM are the most notable carbapenemases associated with resistance mechanisms; the genes encoding these enzymes are found on transferable plasmids thus facilitating the spread of these resistance genes to different species worldwide. KPC-2 is the primary cause of carbapenem resistance among K. pneumoniae isolates in China [45]. However, recently, there have been increasing reports of K. pneumoniae harboring NDM-1 in several Chinese hospitals [6789]. More importantly, K. pneumoniae strains expressing carbapenemase or ESBL genes often co-harbor numerous drug-resistance determinants, such as quinolone and aminoglycoside resistance genes, which are partially responsible for MDR phenotypes; however, to date, little is known regarding the MDR mechanisms of CRKP. In addition, the high prevalence of ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae and the increasing use of carbapenems in our hospital necessitated an investigation of the epidemiology and molecular characterization of CRKP.

In this study, we isolated 78 CRKP strains from patients in our hospital from 2012 to 2015. We investigated the antimicrobial resistance phenotypes and underlying MDR mechanisms of the carbapenem-resistant strains.

A total of 2,932 non-duplicated K. pneumoniae strains were isolated and identified from January 2012 to December 2015 by using the VITEK2 compact or VITEK MS systems (bioMerieux, Hazelwood, MO, USA) at the department of laboratory medicine of the First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University, a major tertiary teaching hospital with 3,200 beds in Southwest China. Seventy-eight strains (2012, n=14; 2013, n=25; 2014, n=10; 2015, n=29) were resistant to at least one carbapenem on the basis of antimicrobial drug resistance determined by using the broth microdilution method [10]. These isolates were recovered from a variety of clinical specimens; urine (23/78,29.5%) was the most frequent source of CRKP, followed by respiratory tract (20/78, 25.6%), blood (9/78, 11.5%), bile (7/78, 9.0%), vaginal secretions (7/78, 9.0%), ascites (6/78, 7.7%), wound secretions (3/78, 3.8%), and abscess (3/78, 3.8%). The study was approved by the Biomedical Ethics Committee of First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University.

Antimicrobial susceptibility to ceftazidime (CAZ), ceftriaxone (CRO), cefepime (FEP), gentamicin (GM), tobramycin (TOB), ciprofloxacin (CIP), and levofloxacin (LEV) were determined initially by using AST GN13 cards on the VITEK2 compact system. The minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of ertapenem (ETP), imipenem (IPM), and meropenem (MEM) were confirmed by using the reference broth microdilution method according to the CLSI methods [10]. The susceptibility testing results were interpreted according to the criteria recommended by the CLSI [11]. Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 was used as the quality control strain for susceptibility testing.

PCR sequencing for the presence of β-lactamase genes, including carbapenemase-related genes (blaKPC, blaNDM, blaVIM, blaIMP, blaSME, and blaOXA-48) and other non-carbapenemase-related genes (blaCTX-M, blaTEM, blaSHV, and blaAmpC), was conducted by using previously described primers and conditions [12]. CRKP isolates were also tested for the presence of aminoglycoside resistant determinants (ARD, including aac(6′)-Ib, armA, and rmtB) and fluoroquinolone resistance determinants (QRD, including qnrA, qnrB, qnrS, and aac(6′)-Ib-cr). PCR analysis of the coding region of the ompK35 and ompK36 genes was performed by using previously described primers [13]. Integrons were screened and sequenced by PCR amplification of integrase genes int1, int2, and int3, as described previously [1415].

To characterize integron variable region gene cassettes, the variable regions of class 1 integrons were further amplified to determine their gene cassette composition by RFLP analysis [16]. PCR products were subsequently digested with the RsaI and HinfI restriction enzymes. Integrons exhibiting the same RFLP patterns were considered to contain identical gene cassettes. Amplified DNA fragments of each distinct class 1 RFLP type integron were sequenced and analyzed by using the BLAST program (National Center for Biotechnology Information).

The transfer experiment was carried out in mixed lysogeny broth cultures. Three CRKP strains co-producing blaNDM-1 and blaKPC-2 (K53, K55, and K65) served as the donors, while E. coli DH5α was used as the recipient strain. Transformants were selected on lysogeny broth agar plates containing 4 mg/L CRO. Similarly, the conjugation experiment was performed according to the previously described method [17] using rifampicin-resistant E. coli EC600 as the recipient strain on MacConkey agar plates in the presence of 8 mg/L CRO and 1,024 mg/L rifampicin. Transformants or transconjugants that grew on the selection medium were isolated, and their antimicrobial susceptibility was characterized by using the VITEK2 compact system (bioMerieux). Plasmid DNA extracted from donors, recipients, transformants, and transconjugants by using the alkaline lysis method was used as the template in PCR analyses. Plasmid replicons were determined by using the PCR-based replicon typing method [18].

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) was conducted to investigate the molecular epidemiology of the 78 CRKP isolates with XbaI-digested and genotyped chromosomal DNA. The genomic DNA restriction patterns of the isolates were analyzed and interpreted according to the previously proposed criteria [19]. In addition, to further determine whether clonal spread influenced the dissemination of carbapenemase-producing K. pneumoniae isolates in our hospital, multi-locus sequence typing (MLST) was performed by amplifying the internal fragments of seven K. pneumoniae housekeeping genes according to the MLST website (http://www.mlst.net).

All analyses were performed by using SPSS v.21.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Univariate analyses were performed separately for each of the variables. Categorical variables were calculated by using a chi-square test or Fisher's exact test as appropriate. Continuous variables were calculated by using Student t-test (normally distributed variables) or Wilcoxon rank-sum test (non-normally distributed variables) as appropriate. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Of the 2,932 non-duplicated K. pneumoniae strains, 78 were resistant to at least one carbapenem and were classified as CRKP. Interestingly, we found a statistically significant increase in CRKP frequency from 1.8% (14/765) in 2012 to 3.6% (29/802) in 2015 (P=0.031), as well as an increase of carbapenemase-producing strains from 28.6% (4/14) in 2012 to 69.0% (20/29) in 2015. Notably, while only six (7.7%) isolates were identified as NDM-1 producers from 2012 to 2014, the prevalence of NDM-1-producing K. pneumoniae increased dramatically to 20.5% (P<0.001) over the 2015.

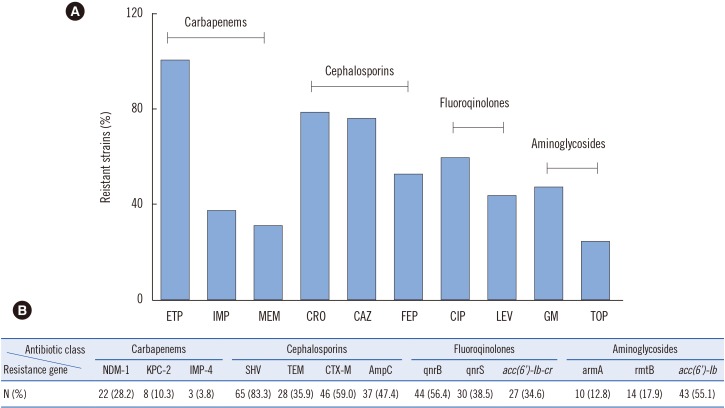

Of the 78 CRKP isolates, the ertapenem resistance rate was 100%, while 37.2% (29/78) and 30.8% (24/78) of the isolates were resistant to IPM and MEM, respectively (Fig. 1). In addition, the resistance rate to cephalosporins was relatively high. Specifically, 78.2%, 75.6%, and 52.5% of the isolates were resistant to CRO, CAZ, and FEP, respectively. The results of the fluoroquinolone testing showed that 46 (59.0%) and 34 (43.6%) isolates were resistant to CIP and LEV, respectively, while the aminoglycoside testing results showed that 37 (47.4%) isolates were resistant to GM, and 19 (24.4%) were resistant to TOB. Notably, 46.2% (36/78) of the CRKP isolates were classified as MDR as they were resistant to three or more classes of antimicrobials.

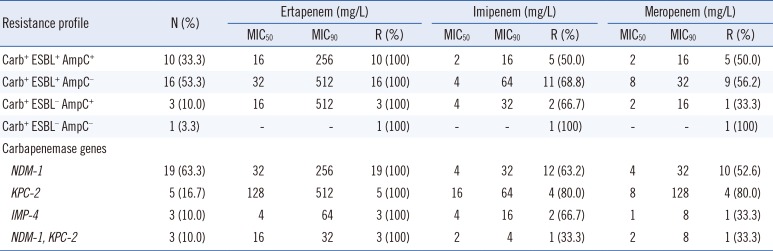

Of the 78 CRKP isolates, 38.5% (30/78) harbored carbapenemase-encoding genes; 22 isolates possessed blaNDM-1, eight isolates contained blaKPC-2, and three isolates had blaIMP-4 (Table 1). It should be noted that the ETM, IPM, and MEM MIC ranges were dramatically higher in isolates possessing both blaNDM-1 and blaKPC-2 than those with only blaNDM-1. Moreover, carbapenemase-producing strains co-expressing blaESBL showed the highest MICs for ETM, IPM, and MEM. Unexpectedly, the MIC50 or MIC90 of three carbapenem agents were dramatically lower in the carbapenemase-producing isolates co-harboring ESBL and AmpC than in isolates positive only for ESBL; however, there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups (MIC50, P=0.268; MIC90, P=0.268).

The remaining 48 non-carbapenemase-producing isolates had a relatively high rate of ESBL genes (36/48, 75.0%) and AmpC enzymes (24/48, 50.0%). In addition to the production of ESBL or AmpC enzymes, deletion or mutation of porins such as OmpK35 and/or OmpK36 has been shown to be correlated with increased carbapenem MICs [20]. Surprisingly, only five (10.4%) of the 48 isolates were found to have defective porin genes, which differ completely from those observed in a multicenter surveillance study conducted in Korea [21]. Subsequent sequencing of the ompK35 and ompK36 genes of the remaining CRKP isolates (73/78) ruled out the occurrence of mutations or insertions, suggesting that these phenotypes were due to decreased expression, protein structure alteration, or inactivation of porins OmpK35 and OmpK36. Therefore, the production of ESBL or AmpC enzymes may have played an important role in carbapenem resistance in our hospital; differences in ESBL combinations or AmpC enzyme expression levels may explain the susceptibility profiles observed.

The prevalence of QRD genes in the 78 CRKP strains was 78.2% (61/78), with 44 strains carrying qnrB, 30 strains carrying qnrS, and 27 strains carrying aac(6′)-Ib-cr; 47.5% of the strains co-expressed at least two types of QRD genes. The prevalence of ARD genes was 65.4% (51/78 strains), and the genes aac(6′)-Ib, armA, and rmtB were detected in 55.1%, 12.8%, and 17.9% of the isolates, respectively; 17.9% of the strains co-expressed at least two types of ARD genes (Fig. 1).

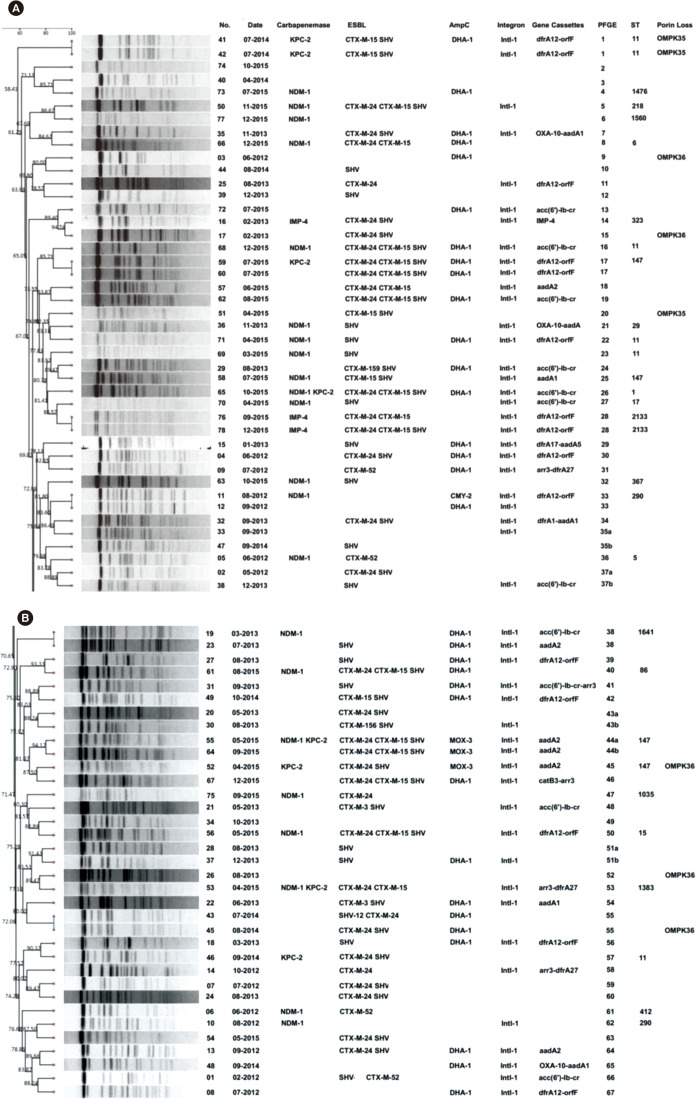

We found that nearly 66.7% (52/78) of the 78 isolates harbored the int1 gene, 45 were identified by amplification of the int1 cassette region, and the length of the amplicons varied from 0.3 kb to 2.6 kb. Gene cassette arrays were divided into 11 distinct types based on their RFLP profile. Moreover, 13 gene cassettes were detected in our study, of which the dfrA12-orfF genes were the most frequent (Fig. 2).

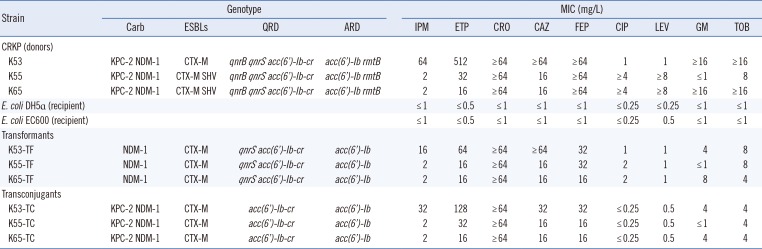

Carbapenem resistance was successfully transferred from three CRKP strains (K53, K55, and K65) to E. coli EC600 by conjugation and to E. coli DH5α by transformation. All E. coli transconjugants exhibited significantly reduced carbapenem susceptibility, with IPM and ETM MICs of 2–32 mg/L and 16–128 mg/L, respectively. In addition, the transconjugants exhibited MDR phenotypes similar to those of the clinical K. pneumoniae isolate donors. The transconjugants were also resistant to cephalosporins, but were susceptible to quinolones and aminoglycosides. Notably, three transconjugants simultaneously harbored blaNDM-1, blaKPC-2, blaCTX-M, acc(6′)-Ib-cr, and acc(6′)-Ib genes, while blaSHV, qnrB, qnrS, or rmtB were not detected in any of the transconjugants. The results of the transformation assays showed that three transformants were resistant to carbapenems and cephalosporins. Similar to the transconjugants, all transformants were susceptible to CIP and LEV; however, a number of transformants exhibited intermediate resistance to GM and TOB. Importantly, the transformation assays enabled the simultaneous transfer of blaNDM-1, blaCTX-M, qnrS, acc(6′)-Ib-cr, and acc(6′)-Ib genes in all of the transformants, while blaKPC-2, blaSHV, qnrB, and rmtB were not detected. In addition, plasmids from K55 and K65 (including those in the donors, transformants, and transconjugants) belonged to plasmid replicon type IncA/C, while the plasmids from K53 were untypeable (Table 2).

As shown in Fig. 2, 67 different XbaI patterns (1 to 67) were identified, indicating that the investigated isolates were epidemiologically unrelated. There were six patterns consisting of two different isolates that were closely related. However, these strains were collected from different wards. MLST demonstrated that sequence type (ST)11 was the most common among the carbapenemase-producing strains (6/30, 20.0%), followed by ST147 (4/30, 13.3%), ST290 (2/30, 6.7%), and ST2133 (2/30, 6.7%). The 22 blaNDM-1 positive strains were divided into 18 different ST patterns, of which the dominant clones, ST11 (3/22) and ST147 (3/22), exhibited diverse PFGE patterns and carried different antibiotic resistance genes. Notably, three isolates possessing both blaNDM-1 and blaKPC-2 belonged to ST1, ST147, and a novel type, ST1383. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report on a K. pneumoniae ST1383 clone possessing blaNDM-1 and blaKPC-2 in China.

In the present study, the most plausible explanation for increased rates of CRKP isolates is the preferential use of carbapenem for the treatment of serious infections in our hospital, which has led to a gradual increase in carbapenem consumption in recent years. Increased usage may result in major selective pressure, thus promoting the progression of carbapenem resistance. As other studies have confirmed the high susceptibility rate of CRKP isolates to colistin and tigecycline [22], combination antibiotic treatment should be considered as the optimal treatment option for severely ill patients with serious infections caused by CRKP. In addition, the incidence of NDM-1 producers among the CRKP in our hospital (28.2%) was much higher than that previously reported in China [6789]. Notably, three NDM-1 isolates co-harbored the blaKPC-2 carbapenemase gene, which also contains other drug-resistance determinants. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report on a MDR CRKP isolate co-harboring blaNDM-1, blaKPC-2, blaCTX-M, blaSHV, acc (6′)-Ib, rmtB, qnrB, and acc(6′)-Ib-cr. CRKP isolates carrying NDM-1 were more likely to be resistant to multiple antibiotics than CRKP strains lacking NDM-1 or other carbapenemases; NDM-1 was often accompanied by other genes encoding resistance to β-lactams, fluoroquinolones, or aminoglycosides, which was in line with a number of previous studies [2324].

Production of ESBL or AmpC enzymes has been demonstrated to play a role in K. pneumoniae resistance to broad-spectrum β-lactams and carbapenems [2]. In our study, we found 81.9% of the NDM-1 isolates co-expressed different ESBL and/or AmpC genes, exhibiting a complex β-lactamase background that was consistent with previous studies [2526]. The SHV-type ESBL gene was the most prevalent among the isolates, followed by the CTX-M-type, which is in agreement with two previous results [2728]. Furthermore, the identification of DHA-1 as the predominant AmpC in the CRKP isolates is similar to the recent findings in China [29].

The present study also demonstrated the qnrB was the most common gene and aac(6′)-Ib-cr was the least frequent gene identified in our hospital. Interestingly, aac(6′)-Ib-cr has been reported to be the most prevalent QRD gene in K. pneumoniae in many countries; these differences are probably due to regional variation in the prevalent resistant isolates [303132]. Most of the CIP and/or LEV resistant isolates identified in this study possessed at least one QRD gene; however, while several isolates were found to carry QRD genes, they exhibited susceptibility to CIP and LEV. Moreover, five isolates resistant to CIP and LEV were negative for QRD genes. Although qnr determinants alone may not confer resistance to quinolones, they do supplement other quinolone resistance mechanisms. Further studies will be required to examine additional resistance mechanisms mediating the high levels of fluoroquinolone resistance such as mutations in chromosomal gyrA and gyrC genes [33] or the presence of efflux pumps encoding genes such as qepA [34].

While many CRKP strains have been shown to be highly multiresistant, aminoglycosides may retain partial bactericidal activity against these isolates [35]. In our study, 52.6% (41/78) of the CRKP isolates were sensitive to at least one of the aminoglycosides tested. The high prevalence of aac(6′)-Ib is likely explained by the fact that the majority of CRKP isolates in our hospital possessed ESBLs; aac(6′)-Ib and ESBL genes are located on the same plasmid [36]. Notably, isolates carrying armA were more resistant to both GM and TOB than strains lacking this gene, suggesting that armA plays an important role in mediating higher aminoglycoside resistance rate.

Integrons, a diverse family of mobile elements, may also play an important role in the rapid evolution of MDR gram-negative pathogens by transferring antimicrobial resistance genes [14]. In the present study, class 1 integron was detected in 66.7% (52/78) of the CRKP isolates, and 13 different gene cassettes were observed in these isolates. The presence of integrons could be associated with resistance to trimethoprim, aminoglycosides, or fluoroquinolones, in agreement with a previous study [37]. Therefore, the wide distribution of integrons in CRKP isolates might pose a serious threat to the development of antimicrobial therapies.

Importantly, we found that all NDM-1 plasmids could be successfully transferred by both transformation and conjugation, whereas transfer of KPC-2 was successful only by conjugation. The most plausible explanation for this finding is that NDM-1 was carried on self-transmissible IncA/C or IncP plasmids, while KPC-2 was located either on non-self-transmissible plasmids or on the chromosome [38]. Moreover, the MICs of IPM and ETM against a number of transconjugants (K53-TC and K55-TC) were much higher than those against the transformants. The cephalosporin and aminoglycoside antimicrobial susceptibility patterns and resistance genes of the E. coli transconjugants were similar to those of the transformants. Interestingly, although both transformants and transconjugants were susceptible to quinolones, the MIC of CIP and LEV was 2- and 4-fold higher against the transformants, respectively, compared with the transconjugants, possibly due to the presence of qnrS in the E. coli transformants. Similar results were also found in a previous study [39].

It should be pointed out that none of the NDM-1 positive patients had a history of travel to any endemic area. Additionally, these NDM-1 isolates could not be attributed to the spread of a single clone, as determined by PFGE analysis; thus, all of the cases were sporadic. This local spread appears to be caused by different factors such as antibiotic abuse, poor infection control precautions, and environmental spread. Given the rapid spread of the NDM-1 carbapenemase in recent years, timely detection and aggressive control approaches are crucial to prevent its establishment as an endemic carbapenemase in our hospital.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates the high prevalence of NDM-1 genes encoding carbapenem resistance among K. pneumoniae isolates in Chongqing, China, as well as a high frequency of MDR determinants among these bacteria. Most importantly, this is the first report on a K. pneumoniae ST1383 clone carrying blaNDM-1 and blaKPC-2 in China and a MDR CRKP isolate co-harboring blaNDM-1, blaKPC-2, blaCTX-M, blaSHV, acc(6′)-Ib, rmtB, qnrB, and acc(6′)-Ib-cr. Because these isolates have limited treatment options, effective surveillance and strict infection control strategies should be implemented to prevent serious infections caused by CRKP in China.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81471992 and 81272545) and the Science Foundation of Yuzhong, district of Chongqing (Grant No. 20140120).

References

1. Hawser SP, Bouchillon SK, Lascols C, Hackel M, Hoban DJ, Badal RE, et al. Susceptibility of Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from intra-abdominal infections and molecular characterization of ertapenem-resistant isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011; 55:3917–3921. PMID: 21670192.

2. Nordmann P, Cuzon G, Naas T. The real threat of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing bacteria. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009; 9:228–236. PMID: 19324295.

3. Pasteran F, Mendez T, Guerriero L, Rapoport M, Corso A. Sensitive screening tests for suspected class a carbapenemase production in species of Enterobacteriaceae. J Clin Microbiol. 2009; 47:1631–1639. PMID: 19386850.

4. Qi Y, Wei Z, Ji S, Du X, Shen P, Yu Y. ST11, the dominant clone of KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in China. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011; 66:307–312. PMID: 21131324.

5. Cai JC, Zhou HW, Zhang R, Chen GX. Emergence of Serratia marcescens, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Escherichia coli Isolates possessing the plasmid-mediated carbapenem-hydrolyzing beta-lactamase KPC-2 in intensive care units of a Chinese hospital. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008; 52:2014–2018. PMID: 18332176.

6. Zhou G, Guo S, Luo Y, Ye L, Song Y, Sun G, et al. NDM-1-producing strains, family Enterobacteriaceae, in hospital, Beijing, China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014; 20:340–342. PMID: 24456600.

7. Zheng R, Zhang Q, Guo Y, Feng Y, Liu L, Zhang A, et al. Outbreak of plasmid-mediated NDM-1-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae ST105 among neonatal patients in Yunnan, China. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2016; 15:10. PMID: 26896089.

8. Jin Y, Shao C, Li J, Fan H, Bai Y, Wang Y. Outbreak of multidrug resistant NDM-1-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae from a neonatal unit in Shandong Province, China. PLoS One. 2015; 10:e0119571. PMID: 25799421.

9. Qin S, Fu Y, Zhang Q, Qi H, Wen JG, Xu H, et al. High incidence and endemic spread of NDM-1-positive Enterobacteriaceae in Henan Province, China. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014; 58:4275–4282. PMID: 24777095.

10. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Methods for Dilution Antimicrobial Tests for Bacteria that Grow Aerobically. Approved Standard, 10th ed. M07-A10. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute;2015.

11. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. 23th informational supplement, M100-S20. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute;2014.

12. Zhang C, Xu X, Pu S, Huang S, Sun J, Yang S, et al. Characterization of carbapenemases, extended spectrum β-lactamases, quinolone resistance and aminoglycoside resistance determinants in carbapenem-non-susceptible Escherichia coli from a teaching hospital in Chongqing, Southwest China. Infect Genet Evol. 2014; 27:271–276. PMID: 25107431.

13. Doumith M, Ellington MJ, Livermore DM, Woodford N. Molecular mechanisms disrupting porin expression in ertapenem-resistant Klebsiella and Enterobacter spp. clinical isolates from the UK. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009; 63:659–667. PMID: 19233898.

14. Bado I, Cordeiro NF, Robino L, García-Fulgueiras V, Seija V, Bazet C, et al. Detection of class 1 and 2 integrons, extended-spectrum β-lactamases and qnr alleles in enterobacterial isolates from the digestive tract of intensive care unit inpatients. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2010; 36:453–458. PMID: 20691572.

15. Correia M, Boavida F, Grosso F, Salgado MJ, Lito LM, Cristino JM, et al. Molecular characterization of a new class 3 integron in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003; 47:2838–2843. PMID: 12936982.

16. Lévesque C, Piché L, Larose C, Roy PH. PCR mapping of integrons reveals several novel combinations of resistance genes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995; 39:185–191. PMID: 7695304.

17. Borgia S, Lastovetska O, Richardson D, Eshaghi A, Xiong J, Chung C, et al. Outbreak of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae containing blaNDM-1, Ontario, Canada. Clin Infect Dis. 2012; 55:e109–e117. PMID: 22997214.

18. Carattoli A, Bertini A, Villa L, Falbo V, Hopkins KL, Threlfall EJ. Identification of plasmids by PCR-based replicon typing. J Microbiol Methods. 2005; 63:219–228. PMID: 15935499.

19. Tenover FC, Arbeit RD, Goering RV, Mickelsen PA, Murray BE, Persing DH, et al. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J Clin Microbiol. 1995; 33:2233–2239. PMID: 7494007.

20. Tsai YK, Fung CP, Lin JC, Chen JH, Chang FY, Chen TL, et al. Klebsiella pneumoniae outer membrane porins OmpK35 and OmpK36 play roles in both antimicrobial resistance and virulence. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011; 55:1485–1493. PMID: 21282452.

21. Kim SY, Shin J, Shin SY, Ko KS. Characteristics of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae isolates from Korea. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013; 76:486–490. PMID: 23688521.

22. Endimiani A, Hujer AM, Perez F, Bethel CR, Hujer KM, Kroeger J, et al. Characterization of blaKPC-containing Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates detected in different institutions in the Eastern USA. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009; 63:427–437. PMID: 19155227.

23. Kumarasamy KK, Toleman MA, Walsh TR, Bagaria J, Butt F, Balakrishnan R, et al. Emergence of a new antibiotic resistance mechanism in India, Pakistan, and the UK: a molecular, biological, and epidemiological study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010; 10:597–602. PMID: 20705517.

24. Ranjan A, Shaik S, Mondal A, Nandanwar N, Hussain A, Semmler T, et al. Molecular epidemiology and genome dynamics of New Delhi Metallo-β-Lactamase-producing extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli strains from India. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016; 60:6795–6805. PMID: 27600040.

25. Zowawi HM, Sartor AL, Balkhy HH, Walsh TR, Al Johani SM, Al Jindan RY, et al. Molecular characterization of carbapenemase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae in the countries of the Gulf cooperation council: dominance of OXA-48 and NDM producers. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014; 58:3085–3090. PMID: 24637692.

26. Gharout-Sait A, Alsharapy SA, Brasme L, Touati A, Kermas R, Bakour S, et al. Enterobacteriaceae isolates carrying the New Delhi mettallo-β-lactamase gene in Yemen. J Med Microbiol. 2014; 63:1316–1323. PMID: 25009193.

27. Tijet N, Sheth PM, Lastovetska O, Chung C, Patel SN, Melano RG. Molecular characterization of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC)-producing Enterobacteriaceae in Ontario, Canada, 2008-2011. PLoS One. 2014; 9:e116421. PMID: 25549365.

28. Uz Zaman T, Aldrees M, Al Johani SM, Alrodayyan M, Aldughashem FA, Balkhy HH. Multi-drug carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae infection carrying the OXA-48 gene and showing variations in outer membrane protein 36 causing an outbreak in a tertiary care hospital in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Int J Infect Dis. 2014; 28:186–192. PMID: 25245001.

29. Hawkey PM, Jones AM. The changing epidemiology of resistance. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009; 64(S1):i3–i10. PMID: 19675017.

30. Jacoby GA, Strahilevitz J, Hooper DC. Plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance. Microbiol Spectr. 2014; 2:PLAS-0006-2013.

31. Rodríguez Martínez JM, Díaz-de Alba P, Lopez-Cerero , Ruiz-Carrascoso G, Gomez-Gil R, Pascual A. Presence of quinolone resistance to qnrB1 genes and blaOXA-48 carbapenemase in clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae in Spain. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2014; 32:441–442. PMID: 24746402.

32. Ruiz E, Sáenz Y, Zarazaga M, Rocha-Gracia R, Martínez-Martínez L, Arlet G, Torres C. qnr, aac(6)-Ib-cr and qepA genes in Escherichia coli and Klebsiella spp.: genetic environments and plasmid and chromosomal location. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012; 67:886–897. PMID: 22223228.

33. Fendukly F, Karlsson I, Hanson HS, Kronvall G, Dornbusch K. Patterns of mutations in target genes in septicemia isolates of Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae with resistance or reduced susceptibility to ciprofloxacin. APMIS. 2003; 111:857–866. PMID: 14510643.

34. Yamane K, Wachino J, Suzuki S, Kimura K, Shibata N, Kato H, et al. New plasmid-mediated fluoroquinolone efflux pump, QepA, found in an Escherichia coli clinical isolate. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007; 51:3354–3360. PMID: 17548499.

35. Almaghrabi R, Clancy CJ, Doi Y, Hao B, Chen L, Shields RK, et al. Carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae strains exhibit diversity in aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes, which exert differing effects on plazomicin and other agents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014; 58:4443–4451. PMID: 24867988.

36. Chen YT, Shu HY, Li LH, Liao TL, Wu KM, Shiau YR, et al. Complete nucleotide sequence of pK245, a 98-kilobase plasmid conferring quinolone resistance and extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase activity in a clinical Klebsiella pneumoniae isolate. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006; 50:3861–3866. PMID: 16940067.

37. Leverstein-van Hall MA, M Blok HE, T Donders AR, Paauw A, Fluit AC, Verhoef J. Multidrug resistance among Enterobacteriaceae is strongly associated with the presence of integrons and is independent of species or isolate origin. J Infect Dis. 2003; 187:251–259. PMID: 12552449.

38. Wu W, Feng Y, Carattoli A, Zong Z. Characterization of an Enterobacter cloacae strain producing both KPC and NDM carbapenemases by whole-genome sequencing. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015; 59:6625–6628. PMID: 26248381.

39. Strahilevitz J, Jacoby GA, Hooper DC, Robicsek A. Plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance: a multifaceted threat. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009; 22:664–689. PMID: 19822894.

Fig. 1

Antimicrobial resistant determinants of 78 carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae (CRKP) isolates. (A) Antibiotic resistance profiles of CRKP isolates: ertapenem (ETP), imipenem (IPM), meropenem (MEM), ceftriaxone (CRO), ceftazidime (CAZ), cefepime (FEP), ciprofloxacin (CIP), levofloxacin (LEV), gentamicin (GM), and tobramycin (TOB). (B) Identification of resistance determinants among the 78 CRKP isolates by PCR.

Fig. 2

Dendrogram of PFGE patterns of chromosomal DNA restriction fragments from the 78 carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae (CRKP) isolates. (A) A dendrogram of PFGE fingerprinting of 43 CRKP isolates. (B) The other dendrogram to show relatedness of PFGE patterns of 35 CRKP isolates. A genetic similarity index scale is shown on the left of the dendrogram. Strain number, collection data, resistance determinants, integron, gene cassettes, PFGE, and MLST types are included by each PFGE lane.

Abbreviations: ESBL, extended-spectrum β-lactamase; PFGE, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis; ST, sequence type.

Table 1

Carbapenem MICs of 30 carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae with different carbapenemase, ESBL, and AmpC combination profiles

Table 2

Antibiotic resistance genes and susceptibility profiles of donors, E. coli EC600, transconjugants, E. coli DH5α, and transformants

Abbreviations: CRKP, carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae; Carb, carbapenemases; ESBLs, expended spectrum β-lactamases; QRD, quinolone resistance determinants; ARD, aminoglycoside resistance determinants; IPM, imipenem; ETP, ertapenem; CRO, ceftriaxone; CAZ, ceftazidime; FEP, cefepime; CIP, ciprofloxacin; LEV, levofloxacin; GM, gentamicin; TOB, tobramycin.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download