Abstract

There has been increasing interest in standardized and quantitative Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) DNA testing for the management of EBV disease. We evaluated the performance of the Real-Q EBV Quantification Kit (BioSewoom, Korea) in whole blood (WB). Nucleic acid extraction and real-time PCR were performed by using the MagNA Pure 96 (Roche Diagnostics, Germany) and 7500 Fast real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, USA), respectively. Assay sensitivity, linearity, and conversion factor were determined by using the World Health Organization international standard diluted in EBV-negative WB. We used 81 WB clinical specimens to compare performance of the Real-Q EBV Quantification Kit and artus EBV RG PCR Kit (Qiagen, Germany). The limit of detection (LOD) and limit of quantification (LOQ) for the Real-Q kit were 453 and 750 IU/mL, respectively. The conversion factor from EBV genomic copies to IU was 0.62. The linear range of the assay was from 750 to 106 IU/mL. Viral load values measured with the Real-Q assay were on average 0.54 log10 copies/mL higher than those measured with the artus assay. The Real-Q assay offered good analytical performance for EBV DNA quantification in WB.

The assessment of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) load is important for monitoring the development of post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder and immunosuppression in transplant patients [123]. Measurement of EBV DNA load has been widely implemented in clinical laboratories since the development of quantitative real-time PCR [4]. However, inter-laboratory comparisons showed significant variability in viral load results [5]. The first EBV international standard (IS) was developed and approved by WHO in 2011, which allowed for recalibration of EBV viral load assays on the basis of the standard [6]. Although the EBV IS should improve agreement between inter-laboratory test results, other factors, such as specimen type (whole blood [WB] or plasma), nucleic acid extraction method, as well as assay instruments, may affect test results [7].

The Real-Q EBV DNA Quantification Kit (BioSewoom, Seoul, Korea) was developed for the quantification of EBV load and approved by the Korean Ministry of Food and Drug Safety [8]. It targets the EBNA1 gene and utilizes the Taqman probe-primers system.

In the present study, we assessed performance of the Real-Q assay for EBV DNA quantification in WB clinical specimens using the WHO IS (code: 09/260, National Institute for Biological Standards and Control [NIBSC], Hertfordshire, UK) [6]. Nucleic acid was extracted by using the MagNA Pure 96 system (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany), and real-time PCR was carried out by using the 7500 Fast real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The results were compared with those obtained using the artus EBV RG PCR Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany).

Briefly, WHO IS containing 5×106 IU EBV DNA was reconstituted in 1 mL of distilled water and further diluted in EBV-negative WB. The EBV-negative WB was obtained from a healthy adult and tested negative for EBV by both the artus and Real-Q assays. DNA extraction for both the artus and Real-Q assays was performed by using the MagNA Pure 96 system using the “Pathogen Universal Protocol” (elution volume of 100 µL), according to the manufacturer's instructions. For EBV DNA detection and quantification using the Real-Q assay, PCR was performed with a total volume of 25 µL (20 µL of PCR reaction mixture including probe and primer mixture and 5 µL of template DNA). Real-time PCR was carried out by using the 7500 Fast (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Five quantitative standards (2.0, 3.0, 4.0, 5.0, and 6.0 log10 copies/µL) were included in each PCR run. The EBV DNA load was calculated from the standard curve and expressed as the number of EBV DNA copies/mL of WB.

The limit of detection (LOD), the lowest concentration of viral DNA load that can be detected in 95% of replicates, was determined by using probit analysis. The limit of quantification (LOQ) was defined as the lowest level of EBV at which the total error was ≤1.0 log10 IU/mL [9]. Serial dilutions of the WHO IS were analyzed with eight replicates per dilution. To estimate the conversion factor, WHO IS was diluted to 5.0, 4.0, and 3.0 log10 IU/mL in EBV-negative WB. Triplicates of the dilutions were analyzed in three consecutive days. The linearity of the real-time PCR assay was determined by analyzing a 10-fold dilution series of the WHO IS, ranging from the LOQ to 6.0 log10 IU/mL. Each dilution was tested in triplicate, and the data were subjected to a linear regression analysis. Cross-reactivity was evaluated by using nucleic acid isolated from seven viruses: cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus (HSV)-1, HSV-2, hepatitis B virus, BK virus, respiratory syncytial virus B, and influenza B virus. To validate the clinical performance of the Real-Q assay, 81 clinical WB specimens were used, and the results were compared with those obtained using the artus EBV RG PCR Kit (Qiagen). The characteristics of each PCR are summarized in the Supplemental Data Table 1.

This study was conducted at a tertiary-care hospital in Seoul, Korea, and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Samsung Medical Center.

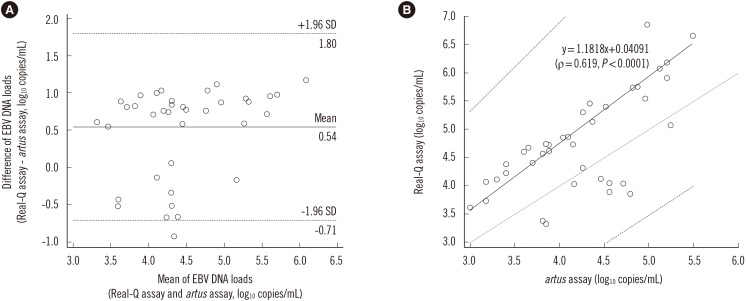

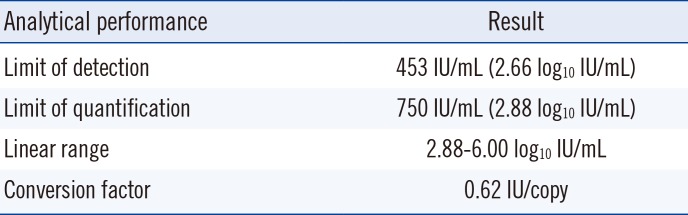

Our results showed that the LOD and LOQ of the Real-Q EBV quantification assay were 453 IU/mL and 750 IU/mL, respectively (Table 1). The conversion factor, calculated as the IS concentration (IU/mL) divided by the mean of 15 EBV genomic copies results (copies/mL), was 0.62. The assay was linear within the range of all samples tested (Fig. 1) (R2=0.9926). No positive signals were observed in the cross-reactivity tests.

A total of 81 clinical WB specimens were tested by using both the Real-Q and artus assays. Thirty-eight specimens were positive by both assays, 13 specimens were positive only by the Real-Q assay, and three specimens were positive only by the artus assay. The concordance between the two assays was 80.2% (65/81). To further compare the two assays, 38 specimens with EBV DNA load above the LOQ in both assays were analyzed by using the Bland-Altman analysis. Viral load values measured with the Real-Q assay were on average 0.54 log10 copies/mL higher than those measured with the artus assay (Fig. 2). A Passing-Bablok regression showed a regression line of Y=1.1818 X+0.04091 (ρ=0.619, P <0.0001). The confidence interval of the slope (1.0404 to 1.5696) excluded 1, but that of the intercept (-1.7070 to 0.6152) included 0, indicating a slight positive proportional bias for the Real-Q assay, but no systematic bias.

A direct comparison for EBV viral load testing can be complicated by several variables including sample type, nucleic acid extraction method, gene target, reagents used, and amplification and detection instruments [410]. Semenova et al [11] demonstrated that multiple methodologies used for quantifying EBV viral load resulted in discrepancies of laboratory test results. Interlaboratory variation in EBV DNA load results was reduced when WHO IS was employed to standardize the results, using the conversion factor for each test. A wide range of conversion factors, from 0.14 to 2.09, was observed in laboratories. In the present study, results obtained by using the Real-Q and artus assays showed divergent log10 copies/mL values. However, we were unable to perform standardization of the log10 IU/mL values because conversion factor for the artus assay was not provided by the manufacturer.

Sample type is one of the most important pre-analytical variables. Various blood components such as WB, plasma or serum, peripheral blood mononuclear cells, and peripheral blood lymphocytes have been used for quantitative EBV testing [12]. Because both cell-free and intracellular viruses can be detected in WB, EBV viral load values in WB are typically higher than those in plasma [41213]. The use of WB allows for a more convenient workflow than the use of plasma, because centrifugation is not required for the former. EBV-negative WB was used as a matrix in all performance evaluations in this study.

Nucleic acid extraction method and real-time PCR instrumentation were previously reported to affect viral load results [14]. In this study, we extracted EBV DNA by automated nucleic acid extraction using the MagNA Pure 96 system. Although we did not compare our results with those obtained using other DNA extraction methods, the Real-Q assay coupled with the MagNA Pure 96 system was a useful clinical tool for EBV quantification in WB. In conclusion, the Real-Q assay offered good analytical performance for EBV DNA quantification in WB.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the Korean Health Technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (HI13C1521).

References

1. Gulley ML, Tang W. Using Epstein-Barr viral load assays to diagnose, monitor, and prevent posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010; 23:350–366. PMID: 20375356.

2. Heslop HE. How I treat EBV lymphoproliferation. Blood. 2009; 114:4002–4008. PMID: 19724053.

3. San-Juan R, Comoli P, Caillard S, Moulin B, Hirsch HH, Meylan P. Epstein-Barr virus-related post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder in solid organ transplant recipients. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014; 20(S7):109–118. PMID: 24475976.

4. Gärtner B, Preiksaitis JK. EBV viral load detection in clinical virology. J Clin Virol. 2010; 48:82–90. PMID: 20395167.

5. Hayden RT, Yan X, Wick MT, Rodriguez AB, Xiong X, Ginocchio CC, et al. Factors contributing to variability of quantitative viral PCR results in proficiency testing samples: a multivariate analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 2012; 50:337–345. PMID: 22116152.

6. Fryer JF, Heath AB, Wilkinson DE, Minor PD. Collaborative study to evaluate the proposed 1st WHO international standard for Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) for nucleic acid amplification (NAT)-based assays. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization;2011.

7. Smith TF, Espy MJ, Mandrekar J, Jones MF, Cockerill FR, Patel R. Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction for evaluating DNAemia due to cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, and BK virus in solid-organ transplant recipients. Clin Infect Dis. 2007; 45:1056–1061. PMID: 17879925.

8. Ha J, Park Y, Shim J, Kim HS. Evaluation of real-time PCR kits for Epstein-Barr virus DNA assays. Lab Med Online. 2016; 6:31–35.

9. CLSI. Evaluation of detection capability for clinical laboratory measurement procedures; Approved Guideline – Second ed. CLSI document EP17-A2. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute;2012.

10. Gullett JC, Nolte FS. Quantitative nucleic acid amplification methods for viral infections. Clin Chem. 2015; 61:72–78. PMID: 25403817.

11. Semenova T, Lupo J, Alain S, Perrin-Confort G, Grossi L, Dimier J, et al. Multicenter evaluation of whole-blood Epstein-Barr viral load standardization using the WHO international standard. J Clin Microbiol. 2016; 54:1746–1750. PMID: 27076661.

12. Ruf S, Behnke-Hall K, Gruhn B, Bauer J, Horn M, Beck J, et al. Comparison of six different specimen types for Epstein-Barr viral load quantification in peripheral blood of pediatric patients after heart transplantation or after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. J Clin Virol. 2012; 53:186–194. PMID: 22182950.

13. Ouedraogo DE, Bollore K, Viljoen J, Foulongne V, Reynes J, Cartron G, et al. Comparison of EBV DNA viral load in whole blood, plasma, B-cells and B-cell culture supernatant. J Med Virol. 2014; 86:851–856. PMID: 24265067.

14. Germi R, Lupo J, Semenova T, Larrat S, Magnat N, Grossi L, et al. Comparison of commercial extraction systems and PCR assays for quantification of Epstein-Barr virus DNA load in whole blood. J Clin Microbiol. 2012; 50:1384–1389. PMID: 22238432.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Data Table S1

Characteristics of molecular assays performed in this study

Fig. 2

Comparison of clinical specimens tested with the Real-Q and artus assays. A total of 38 specimens with EBV DNA load above the limit of quantification in both assays were analyzed. (A) A Bland-Altman plot comparing the artus and Real-Q assays. The solid line represents the mean of difference between copy number values obtained by the Real-Q and the artus assays; dashed lines indicate the 95% confidence interval of the mean of difference. (B) The Passing-Bablok regression analysis. The regression line (solid line) and the 95% confidence interval (dashed lines) are displayed.

Abbreviation: EBV, Epstein-Barr virus.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download