Dear Editor,

Bone marrow (BM) oxalosis is a type of systemic oxalosis wherein oxalate is deposited in BM. It is characterized by cytopenias, leukoerythroblastosis, and hepatosplenomegaly [1] as well as BM findings of calcium oxalate crystals that are birefringent under polarized microscopy and granulomatous structures [2]. Hyperoxaluria (excessive urinary excretion of oxalate) can develop into systemic oxalosis when oxalate is deposited in organs [3]. Hyperoxaluria is classified as primary or secondary. Primary hyperoxaluria is an autosomal recessive disease with defective oxalate metabolism [3] in which the overproduction of oxalate results from an enzyme deficiency in the liver; its clinical presentation involves nephrocalcinosis and renal impairment. Systemic deposition of excess oxalate occurs in the bone and all organs and tissues, except the liver. The retina, arteries, peripheral nervous system, myocardium, thyroid, skin, and BM are the major areas of oxalate deposition. Bone is the most common site, although the bone lesions can mimic clinical renal osteo-dystrophy [45].

Primary hyperoxaluria includes three types of enzyme deficiency. The most common form is primary hyperoxaluria type I, with an incidence rate of approximately 1/120,000 live births per year in Europe. It is caused by a mutation in the AGXT gene resulting in a functional defect of the liver enzyme alanine-glyoxylate aminotransferase and represents 80% of primary hyperoxaluria. Primary hyperoxaluria type II is caused by a deficiency of glyoxylate reductase/hydroxypyruvate reductase (GRHPR), and type III is caused by a deficiency of the mitochondrial enzyme HOGA1 [23]. Secondary hyperoxaluria occurs when dietary and intestinal absorption of oxalate or intake of oxalate precursors is increased and the intestinal microflora is changed [3]. The clinical presentation of secondary hyperoxaluria is similar to that of primary hyperoxaluria, although systemic oxalosis is less common [3]. We present a case of BM oxalosis with pancytopenia in a patient who had been on hemodialysis after bilateral nephrectomy due to recurrent nephrocalcinosis.

A 51-yr-old male patient underwent a BM biopsy due to pancytopenia. He had been on hemodialysis via an arterio-venous graft since 2009 when he underwent a bilateral nephrectomy owing to recurrent renal stones and renal failure. One of his siblings had died owing to end-stage renal disease in his or her 30s (the sex is unknown). The patient had no history of a high-oxalate diet or gastrointestinal symptoms. His complete blood count revealed a Hb level of 5.7 g/dL, white blood cell count of 1.2×109/L (absolute neutrophil count 0.81), and platelet count of 98×109/L. Anemia persisted for five years despite treatment with erythropoietin, and leukopenia and thrombocytopenia also developed. Radiography revealed diffuse sclerotic changes and osteolytic lesions in multiple sites that resulted in a spontaneous fracture in his elbow. Endocrinologically, subclinical hypothyroidism was present with an increased thyroid-stimulating hormone level of 5.344 mIU/L (reference range 0.55-4.78 mIU/L), and a near-normal free thyroxine level of 8.1 ng/L (reference range 8.9-17.8 ng/L). Laboratory data showed the following: blood urea nitrogen, 0.36 g/L, creatinine, 43 mg/L, and erythropoietin 33.2 IU/L (reference rage 4.3-29 IU/L).

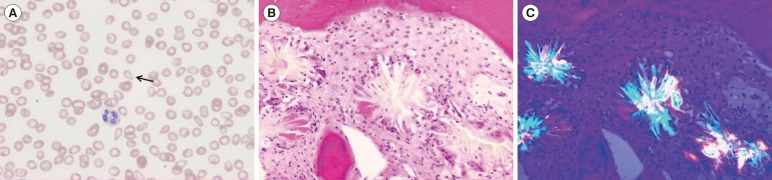

Tear drop cells and left-shifted neutrophils were observed on a peripheral blood smear. BM aspirates were hemodiluted and showed a few multinucleated giant cells. Extensive oxalate crystals depositions surrounded by macrophages and granulomatous formations were revealed on BM biopsy. The crystals were birefringent under polarized microscopy (Fig. 1). The patient demonstrated systemic oxalosis involving the bone, possibly thyroid, and BM, with no evidence of involvement in the retina, arteries, peripheral nervous system, myocardium, or skin.

The familial history of a sibling who had died of end-stage renal disease and the presentation of systemic oxalosis involving bone, thyroid, and BM, and no evidence of a secondary cause, such as diet, suggested a diagnosis of primary hyperoxaluria. However, genetic testing could not be performed because the patient was transferred to a secondary hospital and lost to follow-up.

BM oxalosis is a rare disease presenting with cytopenia, especially treatment-resistant anemia and renal failure [2]. The development of pancytopenia is a rare and late finding [26]. BM aspirate is often hemodiluted owing to crystals. Calcium oxalate crystalline deposits surrounded by granulomatous structures are observed on BM biopsy [2]. Early diagnosis and appropriate conservative treatment is required to prevent the possible complications resulting from cytopenias. Kidney or combined liver and kidney transplantation is the treatment of choice for systemic oxalosis [7].

This is the first case report of BM oxalosis in Korea. BM oxalosis should be considered as a possible diagnosis in patients in renal failure with pancytopenia or treatment-resistant anemia.

Notes

Authors' Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest: No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Go to :

References

2. Taşli F, Özkök G, Ok ES, Soyer N, Mollamehmetoğlu H, Vardar E. Massive bone marrow involvement in an end stage renal failure case with erythropoietin-resistant anemia and primary hyperoxaluria. Ren Fail. 2013; 35:1167–1169. PMID: 23879652.

3. Bhasin B, Ürekli HM, Atta MG. Primary and secondary hyperoxaluria: understanding the enigma. World J Nephrol. 2015; 4:235–244. PMID: 25949937.

5. Lorenzo V, Torres A, Salido E. Primary hyperoxaluria. Nefrologia. 2014; 34:398–412. PMID: 24798559.

6. Sud K, Swaminathan S, Varma N, Kohli HS, Jha V, Gupta KL, et al. Reversal of pancytopenia following kidney transplantation in a patient of primary hyperoxaluria with bone marrow involvement. Nephrology (Carlton). 2004; 9:422–425. PMID: 15663648.

7. Bergstralh EJ, Monico CG, Lieske JC, Herges RM, Langman CB, Hoppe B, et al. Transplantation outcomes in primary hyperoxaluria. Am J Transplant. 2010; 10:2493–2501. PMID: 20849551.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download