Abstract

We report the first Far Eastern case of a Korean child with familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) caused by a novel syntaxin 11 (STX11) mutation. A 33-month-old boy born to non-consanguineous Korean parents was admitted for intermittent fever lasting one week, pancytopenia, hepatosplenomegaly, and HLH in the bone marrow. Under the impression of HLH, genetic study revealed a novel homozygous missense mutation of STX11: c.650T>C, p.Leu217Pro. Although no large deletion or allele drop was identified, genotype analysis demonstrated that the homozygous c.650T>C may have resulted from the duplication of a maternal (unimaternal) chromosomal region and concurrent loss of the other paternal allele, likely caused by meiotic errors such as two crossover events. A cumulative study of such novel mutations and their effects on specific protein interactions may deepen the understanding of how abnormal STX1 expression results in deficient cytotoxic function.

Familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is an inherited autosomal recessive disease that is characterized by defective natural killer (NK) cells and T-cell cytotoxicity and manifests as fever, cytopenia, and tissue hemophagocytosis. Genes known to be altered in familial HLH include PRF1, UNC13D, STX11, and STXBP2, which cause familial HLH subtypes 2 to 5, respectively. Subtype 4 is caused by mutations in the syntaxin 11 gene (STX11) located on chromosome 6q24. The identification of aberrations in STX11 and the abnormal expression of STX11 as the cause of HLH were first reported in Kurdish children [1]. Since then, mutations of STX11 have been reported in approximately 10% of patients with familial HLH, the vast majority of whom have Turkish/Kurdish ethnicity [2]. We report a novel STX11 mutation in familial HLH. It was identified in a Korean child, which is the first report in Korea and also in the Far East.

A 33-month-old boy born to non-consanguineous Korean parents was admitted for intermittent fever lasting one week and abdominal distension. Complete blood count revealed a white blood cell count of 2.09×109/L, hemoglobin level of 10.5 g/dL, and a platelet count of 58×109/L. Serologic study showed fibrinogen levels of 209 mg/dL; triglycerides, 157 mg/dL; and ferritin, 371 ng/mL. Abdominal sonography indicated hepatosplenomegaly, and bone marrow study revealed hemophagocytosis with histiocytic hyperplasia. The test for plasma Epstein-Barr virus DNAemia was negative. The patient's fever and poor general condition persisted, and under the diagnosis of HLH, dexamethasone and etoposide chemotherapy according to the HLH-2004 regimen was started [3]. The patient received unrelated hematopoietic stem cell transplantation from a 1-allele mismatched donor after undergoing busulfan, etoposide, cyclophosphamide, and antithymocyte globulin-based conditioning. He is currently disease free 16 months after transplantation with complete donor chimerism.

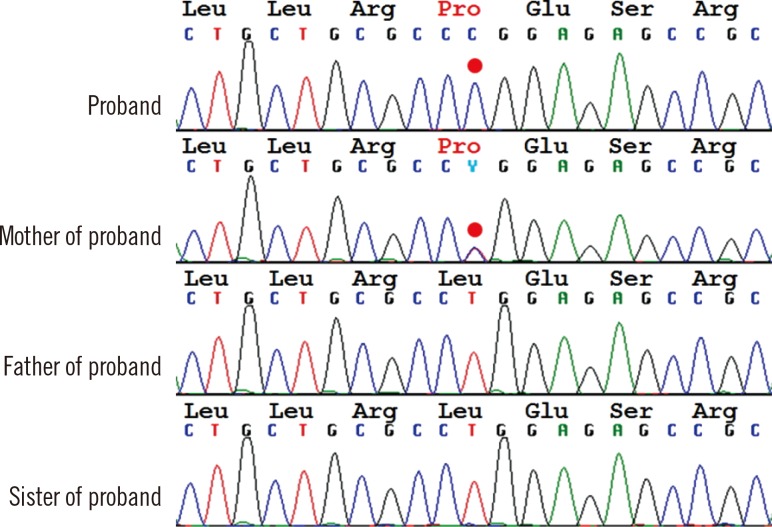

Genetic study for mutations in PRF1, UNC13D, and STX11, performed through direct sequencing of exons and exon-intron boundaries of genomic DNA extracted from peripheral blood leukocytes, revealed a novel homozygous missense mutation in the STX11: c.650T>C, p.Leu217Pro (Fig. 1). Genetic studies of the parents and older sister were performed, and the mother was found to be a carrier of the STX11 mutation, whereas the father and sister were negative for STX11 mutation. Short tandem repeat analysis confirmed the biological relationship of the father and mother with the patient.

To study the possibility of allele dropout, we designed several additional primer sets avoiding single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) sites. The mutation found in the patient was unaffected by allele dropout (i.e. non-amplification of one of the alleles). Long-range PCR covering 9kb of genomic DNA from a portion of intron 1 to exon 2 identified no large deletion breakpoints. Additionally, SNP array with the Sureprint G3 human comparative genomic hybridization (CGH)+SNPMicroarray4x180K kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) confirmed no large heterozygous deletion in STX11 or uniparental disomy in chromosome 6.

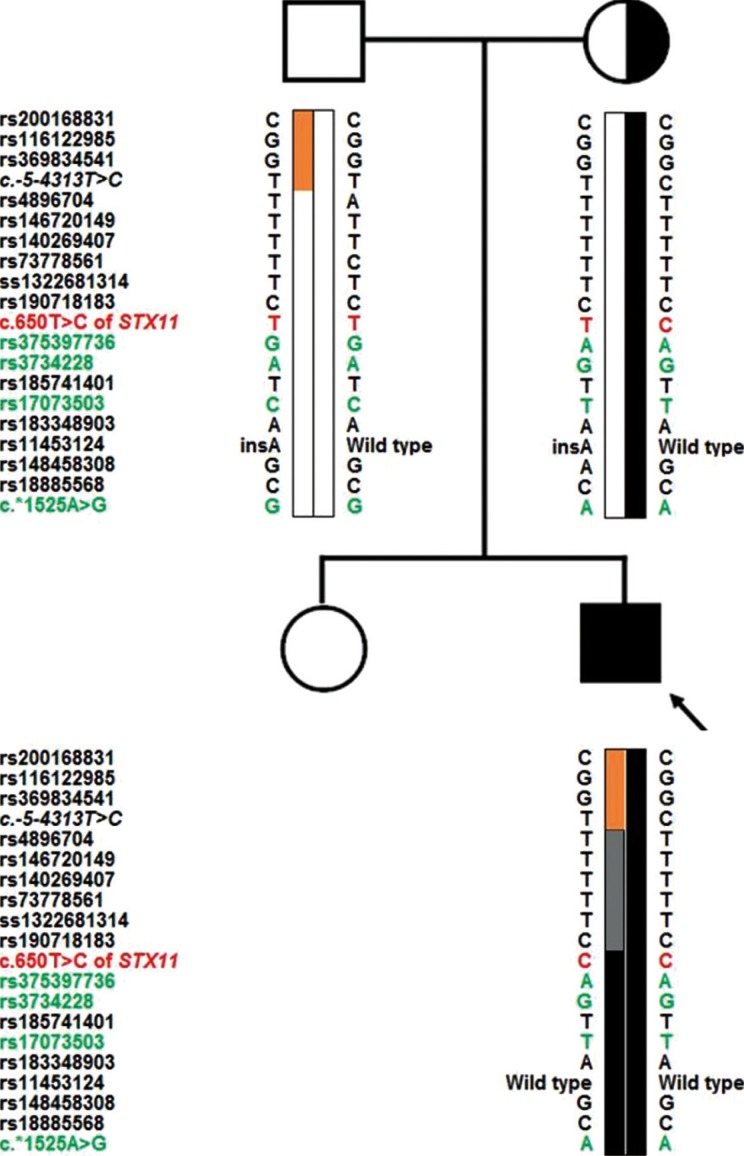

Genotype analysis was performed with 19 SNP markers in an approximately 9-kb region from part of intron1 (c.-5-7000) to part of the 3'untranslated region (UTR; c.*2000) surrounding c.650 of STX11. One haplotype bearing c.650 of STX11 was confirmed to originate from the maternal allele, but the other haplotype harboring the same mutation was suspicious for uniparental disomy (UPD) because it was only partially concordant with the paternal allele (Fig. 2, orange bar).

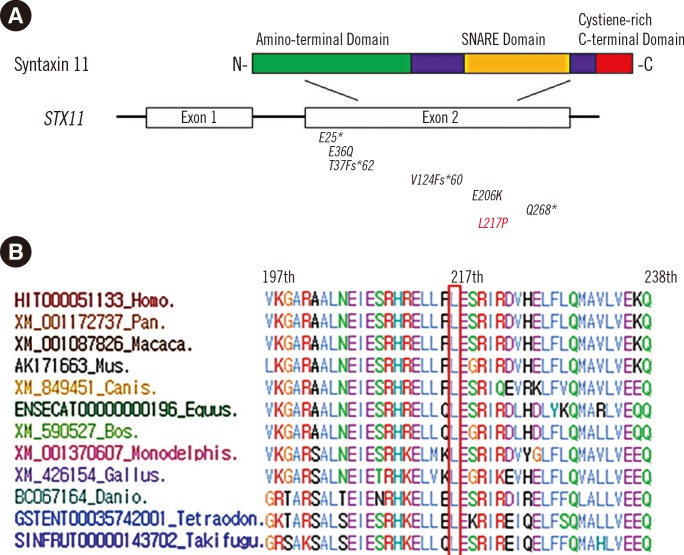

This novel mutation was not listed in dbSNP (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/SNP/) or 1,000 Genomes (http://browser.1000genomes.org/). Because database and literature reviews showed that c.650T>C had not been previously reported in STX11 (Fig. 3A), we performed a control study and found that c.650T>C was not detected in 192 healthy controls in the Korean population. Comparative genomic analysis with Evola (http://www.h-invitational.jp/evola/) demonstrated that the Leu217 residue is conserved across all 12 vertebrate species (Fig. 3B). Bioinformatics analyses with SIFT (http://sift.jcvi.org/) and Polyphen-2 (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/) showed that p.Leu217Pro was predicted to be not tolerated and probably damaging.

Since the initial report associating STX11 mutation with familial HLH, the majority of reported patients with STX11 mutation have been of Turkish or Middle Eastern ethnicity [45]. Korean studies found the UNC13D mutation to be predominant among patients with familial HLH but identified no patients with STX11 mutation [6]. Evaluations undertaken in both Japan and China also failed to identify familial HLH patients with STX11 mutation [78]. Hence, our patient is not only the first familial HLH patient with STX11 mutation of Korean ethnicity but possibly also the first such patient reported from the Far East. Mutations outside the predominant ethnicity have tended to be novel [910].

Of particular note, our patient was homozygous for the STX11 mutation despite having only one parent who carried the mutation. Although neither large deletion nor allele drop was identified, genotype analysis demonstrated that the homozygous c.650T>C may have resulted from duplication of a maternal (unimaternal) chromosomal region and concurrent loss of the other paternal allele. This interstitial UPD is likely associated with meiotic errors such as two crossover events [11].

The various genetic mutations involved in familial HLH result in different clinical disease courses. Patients with PRF1 mutations have earlier disease onset, often during infancy, whereas STX11 mutations may result in onset at a significantly older age [45]. Among patients with STX11 mutations, those with a nonsense mutation may present during infancy, whereas those with biallelic missense mutations may show symptoms at older ages [9].

Our study underscores the hypothesis that STX11 mutation screening in patients with presumed familial HLH is diagnostically relevant regardless of ethnicity. A cumulative study of these novel mutations and their effects on specific protein interactions may lead to greater understanding of how abnormal STX11 expression results in deficient cytotoxic function.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the Korea Health Technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (A120175).

References

1. zur Stadt U, Schmidt S, Kasper B, Beutel K, Diler AS, Henter JI, et al. Linkage of familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (FHL) type-4 to chromosome 6q24 and identification of mutations in syntaxin 11. Hum Mol Genet. 2005; 14:827–834. PMID: 15703195.

2. zur Stadt U, Beutel K, Kolberg S, Schneppenheim R, Kabisch H, Janka G, et al. Mutation spectrum in children with primary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: molecular and functional analyses of PRF1, UNC13D, STX11, and RAB27A. Hum Mutat. 2006; 27:62–68. PMID: 16278825.

3. Henter JI, Horne A, Aricó M, Egeler RM, Filipovich AH, Imashuku S, et al. HLH-2004: diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007; 48:124–131. PMID: 16937360.

4. Horne A, Ramme KG, Rudd E, Zheng C, Wali Y, al-Lamki Z, et al. Characterization of PRF1, STX11 and UNC13D genotype-phenotype correlations in familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Br J Haematol. 2008; 143:75–83. PMID: 18710388.

5. Sepulveda FE, Debeurme F, Ménasché G, Kurowska M, Côte M, Pachlopnik Schmid J, et al. Distinct severity of HLH in both human and murine mutants with complete loss of cytotoxic effector PRF1, RAB27A, and STX11. Blood. 2013; 121:595–603. PMID: 23160464.

6. Yoon HS, Kim HJ, Yoo KH, Sung KW, Koo HH, Kang HJ, et al. UNC13D is the predominant causative gene with recurrent splicing mutations in Korean patients with familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Haematologica. 2010; 95:622–626. PMID: 20015888.

7. Yamamoto K, Ishii E, Horiuchi H, Ueda I, Ohga S, Nishi M, et al. Mutations of syntaxin 11 and SNAP23 genes as causes of familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis were not found in Japanese people. J Hum Genet. 2005; 50:600–603. PMID: 16180048.

8. Zhizhuo H, Junmei X, Yuelin S, Qiang Q, Chunyan L, Zhengde X, et al. Screening the PRF1, UNC13D, STX11, SH2D1A, XIAP, and ITK gene mutations in Chinese children with Epstein-Barr virus-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012; 58:410–414. PMID: 21674762.

9. Marsh RA, Satake N, Biroschak J, Jacobs T, Johnson J, Jordan MB, et al. STX11 mutations and clinical phenotypes of familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in North America. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2010; 55:134–140. PMID: 20486178.

10. Danielian S, Basile N, Rocco C, Prieto E, Rossi J, Barsotti D, et al. Novel syntaxin 11 gene (STX11) mutation in three Argentinean patients with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. J Clin Immunol. 2010; 30:330–337. PMID: 19967551.

11. Engel E. A new genetic concept: uniparental disomy and its potential effect, isodisomy. Am J Med Genet. 1980; 6:137–143. PMID: 7192492.

Fig. 1

Direct sequencing analysis of syntaxin 11 gene (STX11). The proband was homozygous for a missense mutation, c.650T>C, p.Leu217Pro, his mother was heterozygous for the same mutation, and his father and sister had no mutation in the STX11. A base substitution mutation in the second codon position is indicated by the red dots.

Fig. 2

Pedigree and haplotype analysis with the closest markers linked to the mutation. The arrow indicates the proband. The patient's haplotype included paternal (orange) and maternal (black) types in one allele (left). The gray bar indicates an equivocal region in which the maternal and paternal genotypes were identical.

Fig. 3

(A) Domains of the STX11 protein with previously reported STX11 mutations (black) and the patient's novel mutation, c.650T>C (red). (B) Comparative genomic analysis. The Leu217 residue of STX11 is highly conserved across all 12 vertebrate species according to Evola (http://www.h-invitational.jp/evola/).

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download