The diagnosis of Philadelphia-negative myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN) depends on bone marrow (BM) examination and Janus kinase 2 (

JAK2) V617F mutation analysis [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5].

JAK2 exon 12 mutations and thrombopoietin receptor (

MPL) mutations are useful markers to diagnose JAK2 V617F-negative MPN. However, since these mutations occur in <5% of

JAK2 V617F-negative MPNs, they have limited clinical relevance [

6,

7,

8]. Recently, somatic mutations in exon 9 of calreticulin (

CALR) were identified as a new diagnostic tool in

JAK2 V617F-negative MPNs, which were detected in 67% of the patients with essential thrombocythemia (ET) and 88% of patients with primary myelofibrosis (PMF) without

JAK2 V617F mutation [

9]. Subsequent studies reported a trend of lower white blood cell (WBC) counts and hemoglobin levels, higher platelet counts, and more indolent clinical course in ET and PMF patients carrying

CALR mutations than those carrying the

JAK2 V617F mutation [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. Furthermore,

CALR mutations were proposed as a new diagnostic tool for ET and PMF in the revised WHO classification system [

16].

However, favorable clinical outcome in MPN patients carrying

CALR mutations has not been confirmed since myelofibrosis progression is also reported to have high incidence in ET patients with

CALR mutations [

15]. Moreover, studies in Asian populations are currently outnumbered since only 3 studies have evaluated this issue, but these studies have not included the Korean population [

17,

18,

19]. Therefore, we analyzed the incidence, clinical features, and prognostic impact of

CALR mutations in patients diagnosed as having ET and PMF at a single tertiary hospital in Korea.

Forty-eight patients diagnosed as having ET and 14 diagnosed as having PMF at Pusan National University Hospital from May 2007 to June 2014, according to the WHO diagnostic criteria classifications of 2008 [

1] were included in this study. ET patients were managed with hydroxyurea only (32 patients), hydroxyurea and anagrelide (four patients), anagrelide only (six patients), or close monitoring without treatment (six patients). PMF patients were managed with hydroxyurea only (five patients), hydroxyurea and anagrelide (two patients), anagrelide only (two patients), oxymetholone only (two patients), or close monitoring without treatment (three patients).

JAK2 V617F mutation analysis was performed by using Seeplex JAK2 ACE Genotyping kit (Seegene, Seoul, Korea), and the median follow-up period in 62 patients was 7.73 months (range, 0.03-76.63 months). In 30 ET and PMF patients without

JAK2 V617F mutation, both

JAK2 exon 12 and

MPL exon 9 mutation analyses were performed retrospectively by direct sequencing using in-house designed primers (JAK2-12-F, 5'-CTCCTCTTTGGAGCAATTCA-3'; JAK2-12-R, 5'-CCAATGTCACATGAATGTAAATCAA-3'; MPL-F, 5'-CCGAAGTCTGACCCTTTTTG-3'; MPL-R, 5'-ACAGAGCGAACCAAGAATGC-3').

For

CALR mutation analyses, PCR (F, 5'-GGCAAGGCCCTGAGGTGT-3'; R, 5'-CAGGCCTCAGTCCAGCCCTG-3'; 95℃ for 1 min, 35 cycles at 95℃ for 15 sec, 60℃ for 15 sec, and 72℃ for 30 sec, followed by extension at 72℃ for 7 min) was followed by direct sequencing. After confirming the presence of a single 267-base pair band (wild type) and multiple bands (mutation) in electrophoresis, direct sequencing was performed by using an ABI 3130 genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems Inc., Foster city, CA, USA). Identified mutations were aligned with a reference sequence (NM_004343.3, c.1054_1254), while the novelty of the mutations was determined by screening a published database [

9].

Clinical data of patients was obtained through retrospective review of electronic medical records, including gender, age, complete blood cell counts, BM cellularity, megakaryocyte counts, BM fibrosis grade, history of thrombosis, bleeding or acute myeloid leukemia transformation, survival rates at one year, overall survival (OS, the period between the initial diagnosis and last follow-up or death), and karyotype. Thus, prognostic scores according to Dynamic International Prognostic Scoring System (DIPSS) [

20] were measured in 14 PMF patients. Both 48 ET and 14 PMF patients were classified into the following three subgroups according to

JAK2 V617F and

CALR mutation status: (1),

JAK2(-)/

CALR(-); (2),

JAK2(+)/

CALR(-); (3),

JAK2(-)/

CALR(+). The clinical features, DIPSS scores (in PMF cases), and prognosis were compared among the three subgroups. This study was approved by the review board of the Pusan National University Hospital, and informed consent was obtained from all patients.

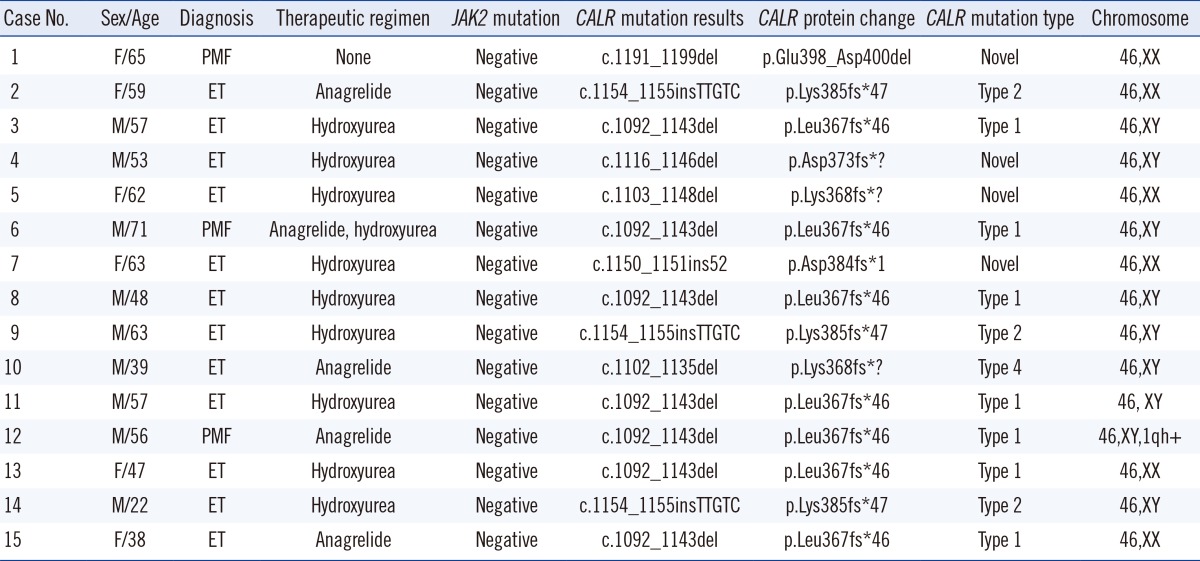

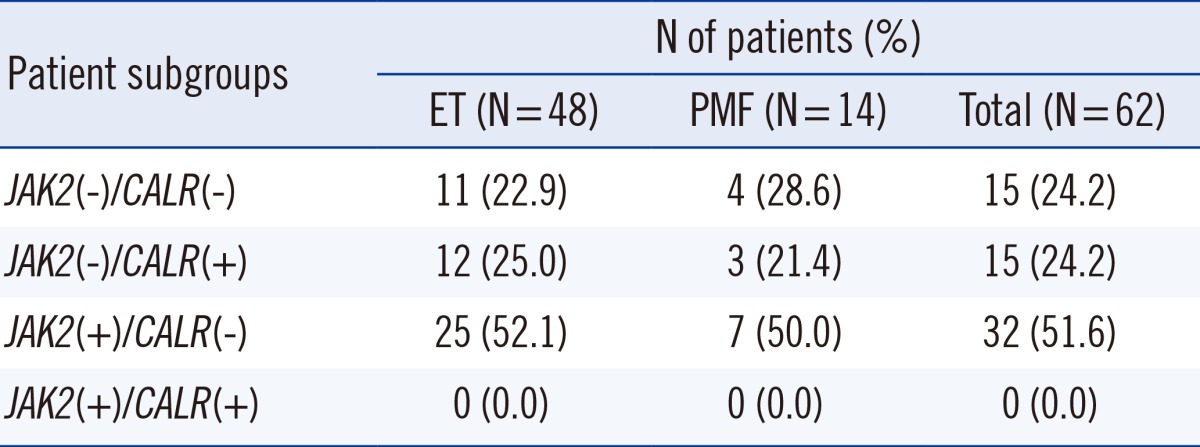

Among 62 patients,

JAK2 V617F mutation was detected in 32 (51.6%) patients, while

CALR mutations were identified in 15 (24.2%) patients. Fifteen (24.2%) patients did not have

JAK2 or

CALR mutations, while there were no patients with both mutations. Among 30 patients without the

JAK2 V617F mutation,

CALR mutations were detected in 15 (50.0%) patients but

JAK2 exon 12 or

MPL exon 9 mutations were not found in these patients (

Table 1). Among 15 patients carrying

CALR mutations, seven patients showed a 52-base pair deletion (c.1092_1143del), defined as the most frequent mutation (type 1) [

9], three patients showed a 5-base pair insertion (c.1154_ 1155insTTGTC), defined as a frequently detected mutation (type 2) [

9], while one patient showed a previously defined mutation type 4 (c.1102_1135del) [

9]. Four patients were identified with novel mutations (c.1191_1199del, c.1116_1146del, c.1103_1148del, and c.1150_1151ins52) (

Table 2).

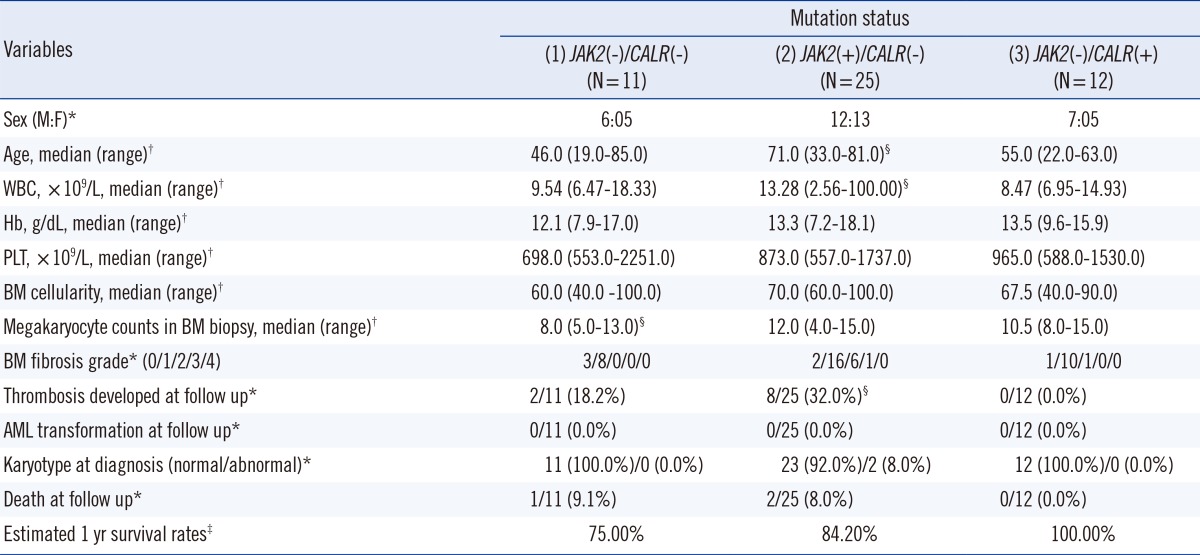

Among 48 ET patients, those carrying

CALR mutations were significantly younger (

P=0.036) but had lower WBC counts (

P=0.022) and less thrombosis development during follow-up (

P=0.036) than those with the

JAK2 V617F mutation. Patients carrying

CALR mutations did not show significant differences in platelet counts, 1-yr survival rates, death rates, and OS (

P=0.341) compared with those carrying the

JAK2 V617F mutation. Among the 23 ET patients without the

JAK2 V617F mutation, the clinical features and OS (

P=0.221) of the patients carrying

CALR mutations were not significantly different from those without

CALR mutations, although higher megakaryocyte counts in BM biopsy (

P=0.020) were observed in the former group (

Table 3).

In PMF, three patients carrying CALR mutations showed significantly lower WBC counts (median 4.30×109/L vs. 22.77×109/L, P=0.016) and tended to have lower hemoglobin levels (median 8.3 g/dL vs. 11.0 g/dL, P=0.087) than did seven patients carrying the JAK2 V617F mutation. No significant differences in other clinical features, prognosis, and DIPSS scores (median 2.0 [0.0-3.0] in patients carrying CALR mutations vs. 1.0 [0.0-3.0] in those carrying the JAK2 V617F mutation, P=0.400) were observed between the two subgroups. Among patients without the JAK2 V617F mutation, no significant differences in clinical features, prognosis, and DIPSS scores (median 2.0 [0.0-3.0] vs. 2.5 [2.0-4.0], P=0.999) were observed between three patients with CALR mutations and four without CALR mutations, although significantly higher WBC counts were detected in the former group (median 4.30×109/L vs. 2.31×109/L, P=0.034).

Our data evidenced that the incidence of

CALR mutations is 24.2% in ET and PMF, while the mutation frequency increased to 50.0% in patients without the

JAK2 V617F mutation, irrespective of the specific disease subtype. The incidence of

CALR mutations reported herein is slightly lower than that reported by Klampfl et al. [

9], while it is similar to the results in other studies (24% and 31% in ET and 20% in PMF) [

10,

15]. Our results are also similar to previous reports on Asian populations (22.5% and 26.3% in ET and 21% in PMF) [

17,

18,

19]; hence, the frequency of

CALR mutation in ET and PMF is suggested to be independent of ethnic variations. Our data indicated that by introducing a

CALR mutation analysis, 50% of the patients suspected of having ET and PMF but without the

JAK2 V617F mutation could be diagnosed correctly.

Consistent with previous reports, we demonstrated that ET patients carrying

CALR mutations have distinct clinical features such as younger age, lower WBC counts, and lower thrombosis risk than those carrying the

JAK2 V617F mutation [

9,

10,

14,

15]. In contrast with previous studies, we did not find significant differences in hemoglobin levels and platelet counts in ET patients with respect to their

JAK2 V617F and

CALR mutation status [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. Additionally, our data indicated that the

CALR mutation status has no influence on clinical features, including prognosis in ET patients without the

JAK2 V617F mutation. Considering the small size of each subgroup, lack of statistical power might be a major limitation of our study, thus explaining the discrepancy with previous data. Similarly, the comparison of clinical features in PMF patients with respect to

JAK2 V617F and

CALR mutation status might have been affected by the small size of each subgroup. Therefore, additional large-scale studies are required to confirm the clinical relevance of

CALR mutations in ET and especially in PMF patients.

In conclusion, the incidence of CALR mutations in ET and PMF was 24.2% and increased to 50.0% in JAK2 V617F-negative cases. ET patients carrying CALR mutations were younger, showed lower WBC counts, and experienced less thrombosis than did those carrying the JAK2 V617F mutation, although no differences in other clinical features and prognosis were demonstrated. Furthermore, in ET patients without the JAK2 V617F mutation, the presence of CALR mutations had no influence on clinical manifestation and prognosis. CALR mutation analysis can therefore be a useful additional diagnostic tool for ET and PMF, although the prognostic impact of CALR mutations should be addressed in more detail in future studies.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download