Abstract

The Ael subgroup expresses the least amount of A antigens and could only be detected by performing the adsorption-elution test. The frequency of the Ael subgroup is about 0.001% in Koreans, and the Ael02 allele, which originates from A102, is the most frequently identified allele in the Korean population. We report a Korean family with the Ael03 allele identified by molecular genetic analysis. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first such report in Korea to date.

Ael is a rare subgroup in the A blood type that expresses the least amount of A antigens, comprising about 1/1,000 of the antigen determinants of A1. The frequency of the Ael phenotype has been estimated to be about 0.001% in the Korean population [1] and 0.0049% in the Japanese population [2]. Ael02 is the most frequently identified allele [3]. Red blood cells (RBCs) of the Ael subtype show no agglutination at all in the anti-A or anti-A,B sera, and A antigens on RBCs could only be detected by the adsorption-elution test, which is known as the most sensitive method for detecting the A subgroup. In this report, we found a Korean patient with weak A antigens by performing the adsorption-elution test, and the weak A antigen was identified to be Ael03 via molecular genetic analysis. We also performed ABO genotyping of his family and eventually found that his descendant possessed the Ael allele. Interestingly, this appearance of the Ael03 allele has not been reported previously, and to the best of our knowledge, this is the first such case in the Korean population.

A 48-yr-old man visited the outpatient clinic of Korea University Ansan hospital in July 2013 for the removal of common bile duct stones by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. He knew that his blood type as O, but weak A antigens were noticed after several serologic tests, including the adsorption-elution test. The patient's blood type was suspected to be in the Ael subgroup, since the A antigen was only detectable by the adsorption-elution test. We also tested his family serologically and performed molecular genetic analysis for exact typing. The family did not have any illness or a medical history.

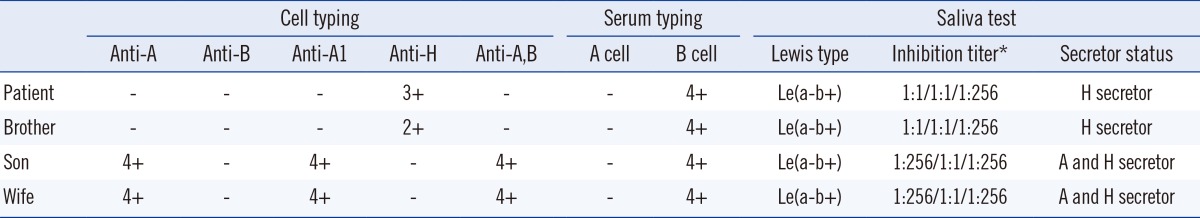

Routine ABO typing of the patient's blood showed the result of phenotype O with only anti-B: negative reactions were observed for anti-A (Bioscot, Livingston, UK), anti-B (Bioscot), anti-A1 (Ortho clinical diagnostics, Raritan, NJ, USA), and anti-A,B (Ortho clinical diagnostics), and positive reactions were observed for anti-H (Imumed, Bammental, Germany) and B cells. Serum typing after the addition of enough serum and 30 min of incubation at 37℃ yielded same results as that observed for the initial serum typing. The results of the patient's brother showed the same pattern as those of the patient. The patient's wife and son had type A blood (Table 1).

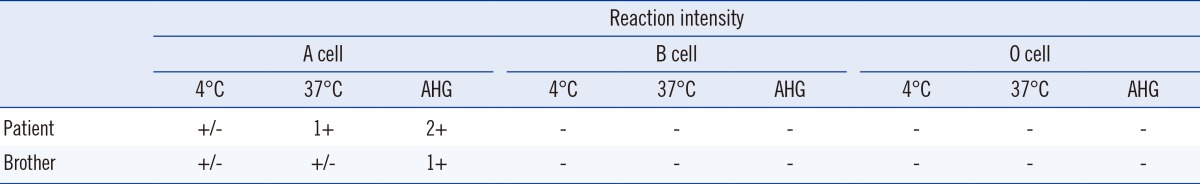

For the adsorption-elution test, 1 mL of patient's RBCs was mixed with 1 mL of anti-A at 4℃ for an hr. After centrifuging, the supernatant was discarded, and RBCs were washed with normal saline. Then, the same amount of normal saline was added, and the bound antibodies were eluted in a 56℃ bath for 10 min. In our case, the elution reacted with A cells at 4℃ and 37℃, after addition of antihuman globulin. Thus, the patient's weak A antigens were detected. This test was also performed for the patient's brother and the same pattern was observed (Table 2). The patient's irregular antibody screening test was negative, and serum immunoglobulin levels were within the reference range. We did not observe A substance in the saliva of the patient and his brother (Table 1).

ABO genotyping was performed after obtaining an informed consent from the patient and his family.

Genomic DNA from peripheral blood was extracted using a DNA Extraction Kit (Qiagen Inc., Chatsworth, CA, USA). For PCR, Exon 7 of the ABO gene that encodes for the catalytic domain of the transferase was amplified using three sets of primers previously delineated [4] with the GeneAMP PCR system 9700 (Applied Biosystems, Foster city, CA, USA). Amplified fragment products were subsequently digested by the restriction enzyme Kpnl, and it resulted in specific fragment patterns by electrophoretic separation on agarose gels. After the purification of PCR products, sequencing was performed by using the ABI 3130 Genetic Analyser (Applied Biosystems), and the products were analyzed using the SEQUENCHER (Gene Codes Corp, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) v5.1 demo software program.

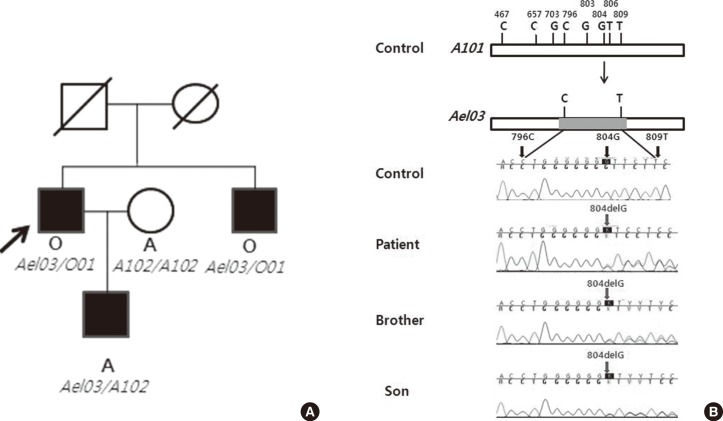

Each result was compared with the consensus sequence of the A101 allele. We identified that the patient and his brother had the exactly same genotype, Ael03/O01. The patient's son had a genotype of Ael03/A102, one haplotype Ael03 allele from his father and the other haplotype A102 allele from his mother. The patient, his brother, and his son had the Ael03 allele in common, resulting in a frame shift mutation caused by a single-base deletion at nucleotide 804 (Fig. 1).

To resolve ABO discrepancy, we performed several tests described above. There is a domestic report that Ael may have anti-A antibody in the serum, which is usually less reactive with the reagent red cells than the anti-B antibody, resembling the O phenotype [5]. However, our patient showed no agglutination by anti-A and anti-B test sera and had only anti-B antibody in the serum, suggesting weak A phenotype. We confirmed the weak A phenotype with the adsorption-elution test. No A substance was found in the saliva test of the patient. Considering that the A antigens were detected only by the adsorption-elution test, the presence of the Ael subgroup was suspected. Exon7 of the ABO gene was analyzed by direct sequencing, and we identified that the patient possessed the Ael03 allele. His brother and his son were also found to possess Ael03. We could not perform molecular genetic analysis of the parents.

It is known that seven types of Ael alleles exist [2], and the mutations of six types, except Ael04, lie within exon 6 and exon 7 [3]. So far, there have been reports on two kinds of Ael allele variants in the Koreans; one is the Ael01 allele that has a C467T (Pro156Leu) substitution, and the other is the Ael02 allele that contains the T646A (Phe216Ile) and G681A (silent mutation) substitution beside the C467T substitution. A102 is the most frequently identified allele in the Korean and Japanese populations [6, 7] and Ael02 is thought to have originated from A102 [8]; therefore, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of Ael03 in the Korean population, and is highly significant.

The patient (Ael03/O01) showed the result for phenotype O with only anti-B. The reason that Ael03 was manifested as O seems to be the lack of allelic enhancement of Ael03. Allelic enhancement occurs when one ABO allele gains antigenicity when it is combined with the A allele or B allele. However, this allelic enhancement does not explain all the discrepancies between genotype and phenotype, because there are several reports about the Ael phenotype where the O allele exists [5, 8]. The results of the patient's son (Ael03/A102) revealed that Ael03 expression was affected by the co-inherited allele A, resulting in its expression as A and indicating a gain of allelic enhancement in Ael03. In conclusion, Ael03 could be expressed as phenotype O or A depending on the co-inherited allele. There are domestic family studies about Ael02 and B306, which showed different phenotypes depending on the co-inherited ABO allele [3, 9].

As molecular genetic studies develop, understanding of polymorphism in the blood group system becomes clearer and broader. This case shows that a single-base deletion resulted in a frame shift mutation and caused a change in blood group A glycosyltranseferase activity. These results can explain the presence of weak A antigens in serologic tests. The present case highlights the importance and necessity of molecular genetic studies in the research of molecular genetic heterogeneity within Ael subgroups and in determining ABO subgroups. Furthermore, we recognize concerns about phenotypic changes when the relevant allele is combined with A or B.

References

1. Cho D, Shin MG, Yazer MH, Kee SJ, Shin JH, Suh SP, et al. The genetic and phenotypic basis of blood group A subtypes in Koreans. Transfus Med. 2005; 15:329–334. PMID: 16101812.

2. Okiura T, Fukumori Y, Nishimura K, Orimoto C, Fujii K, Nishimukai H. A-elute alleles of the ABO blood group system in Japanese. Leg Med (Tokyo). 2003; 5(S1):S207–S209. PMID: 12935591.

3. Choi HW, Cho D, Jeon MJ, Lee JS, Song JW, Shin MG, et al. A family study of Ael02 allele expressing different phenotypes depending on co-inhereted ABO alleles. Korean J Blood Transfus. 2006; 17:146–152.

4. Seo DH, Lee CY, Kim DW, Kim SI. ABO gene analysis of cis-AB and B subgroup in blood donors. Korean J Blood Transfus. 2000; 11:27–34.

5. Joo SY, Shim YS, Kim MJ, Kwon HL, Lee K, Chang HE, et al. A case of ABO*Ael02/O04 genotype with typical phenotype O. Korean J Lab Med. 2008; 28:319–324. PMID: 18728383.

6. Kang SH, Fukumori Y, Ohnoki S, Shibata H, Han KS, Nishimukai H, et al. Distribution of ABO genotypes and allele frequencies in a Korean population. Jpn J Hum Genet. 1997; 42:331–335. PMID: 9290258.

7. Ogasawara K, Bannai M, Saitou N, Yabe R, Nakata K, Takenaka M, et al. Extensive polymorphism of ABO blood group gene: three major lineages of the alleles for the common ABO phenotypes. Hum Genet. 1996; 97:777–783. PMID: 8641696.

8. Ogasawara K, Yabe R, Uchikawa M, Nakata K, Watanabe J, Takahashi Y, et al. Recombination and gene conversion-like events may contribute to ABO gene diversity causing various phenotypes. Immunogenetics. 2001; 53:190–199. PMID: 11398963.

9. Cho D, Kim SH, Ki CS, Choi KL, Cho YG, Song JW, et al. A novel B(var) allele (547 G>A) demonstrates differential expression depending on the co-inherited ABO allele. Vox Sang. 2004; 87:187–189. PMID: 15569071.

Fig. 1

The pedigree and the results of sequencing. (A) Pedigree demonstrating the inheritance of the Ael03 allele. The phenotype and genotype are indicated below each symbol. The arrow indicates proband. (B) Schemes for generation of frame shift mutation caused by single-base deletion at nucleotide 804.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download