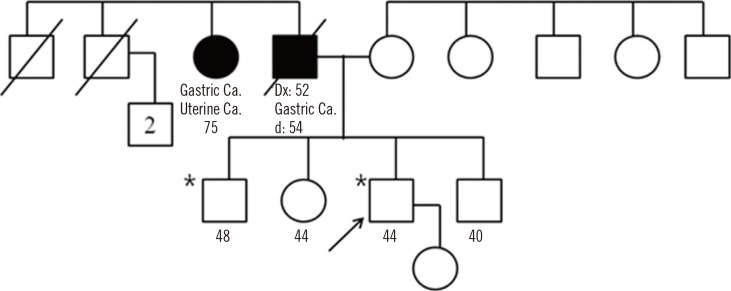

| Fig. 1Pedigree of the individual's family in our case. Solid symbol represents the individual with tumor(s). Types of tumors are indicated, along with ages (yr) at the time of diagnosis and death (if applicable). An asterisk (*) marks the examined individual found to carry the germline CDH1 mutation. Arrow indicates this case.

Abbreviations: Dx, diagnosis; d, death; Ca, cancer.

|

Abstract

Gastric cancer (GC) is one of the most common cancers with high morbidity and mortality. Familial GC is seen in 10% of cases, and approximately 3% of familial GC cases arise owing to hereditary diffuse gastric cancer (HDGC). CDH1, which encodes the protein E-cadherin, is the only gene whose mutations are associated with HDGC. Screening for the familial GC-predisposing gene has been neglected in high-risk countries such as Korea, China, and Japan, where all the cases have been attributed to Helicobacter pylori or other carcinogens. Screening for the GC-causing CDH1 mutation may provide valuable information for genetic counseling, testing, and risk-reduction management for the as-yet unaffected family members. An asymptomatic 44-yr-old Korean male visited our genetic clinic for consultation owing to his family history of GC. Eventually, c.1018A>G in CDH1, a known disease-causing mutation, was found. As of the publication time, the individual is alive without the evidence of GC, and is on surveillance. To our knowledge, this is the first Korean case of presymptomatic detection of CDH1 mutation, and it highlights the importance of genetic screening for individuals with a family history of GC, especially in high-risk geographical areas.

Go to :

Gastric cancer (GC) is relatively common around the world, mainly in its sporadic form; however, familial aggregation of the disease may be seen in approximately 10% of GC cases [1]. The prevalence of GC in Korea is high, with crude incidence rates in men and women of 86.8 and 41.1 per 100,000 person-years, respectively, in 2012 [2]. Because the stage of GC at the time of detection correlates with prognosis, cancer screening is important for early detection, with nationwide screening programs being enforced for the promotion of cancer screening in Korea [3]. The detection of GC at an early stage has increased. However, genetic causes of GC can be easily overlooked in an area with a high occurrence of stomach cancer, such as Korea, possibly because of the causes being attributed to Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection, diet, and life style [4].

Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer (HDGC) is an autosomal dominant disorder caused by germline mutation of the cadherin-1 gene (CDH1), which encodes the cell-to-cell adhesion protein E-cadherin. Early diagnosis of HDGC is very difficult because the tumor cells begin infiltrating the mucosa while preserving a normal surface epithelium, and visible lesions can rarely be spotted endoscopically [5]. In such cases, recent advances in molecular medicine have not only clarified the carcinogenesis of GC, but have also offered novel approaches regarding GC prevention, diagnosis, and therapeutic intervention [6].

To our knowledge, this is the first report on presymptomatic identification of CDH1 mutation in a Korean individual with a family history of diffuse GC (DGC). Being exposed to medical information on genetic mutations associated with GC through a newspaper article, a 44-yr-old male visited our genetic counseling clinic for genetic testing of the gene associated with GC. He showed no specific symptoms or anomalous findings on physical examination, as well as no known history of other genetic disorders. His father died of GC at the age of 54; and a year after GC diagnosis at the age of 52, one of his paternal aunts showed terminal-stage GC (Fig. 1). However, histological diagnosis was not known or performed for his father and aunt. To be diagnosed with HDGC, a family should meet the criteria proposed by the International Gastric Cancer Linkage Consortium (IGCLC) [7], which includes the followings: 1) two or more documented cases of DGC in first- or second-degree relatives, with at least one case diagnosed before the age of 50 yr; or 2) three or more cases of documented DGC in first- or second-degree relatives, independent of their ages. Previously, 25-50% of the families fulfilling the criteria for HDGC were shown to have germline mutations in CDH1 [7, 8]. Considering the family history, genetic analysis of the CDH1 was performed with the patient's written informed consent; the analysis did not fulfill the clinical criteria of HDGC as defined by the IGCLC.

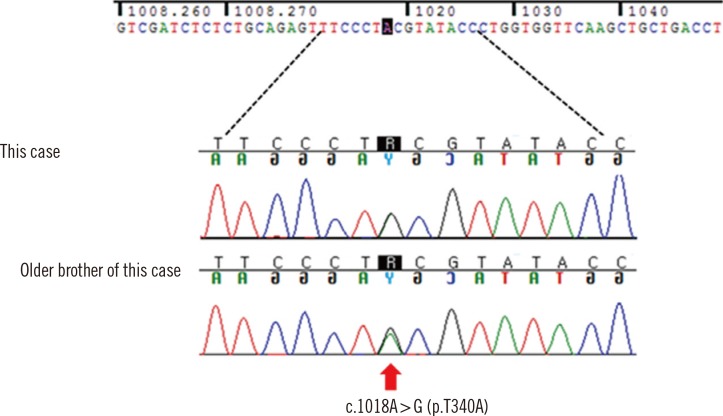

Genomic DNA was extracted from the individual's peripheral blood leukocytes by using Wizard Genomic DNA Purification kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. All the coding exons and flanking intronic regions of CDH1 were amplified by using the primer sets we designed (available on request). PCR was performed by using a thermal cycler (Model 9700; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Five microliters of the amplification product was treated with 2 U of shrimp alkaline phosphatase and 10 U exonuclease I (USB Corp., Cleveland, OH, USA). Direct sequencing was per-formed by using BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction Kit and an ABI Prism 3130 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). The obtained sequences were analyzed by using the Sequencher program (Gene Codes Corp., Ann Arbor, MI, USA) and were compared with a reference sequence (GenBank accession number NM_004360.3).

The sequencing revealed that he had a known heterozygous mutation in codon 340 of CDH1, resulting in an amino acid change from threonine to alanine (c.1018A>G, p.Thr340Ala) (Fig. 2). Although he showed no specific symptoms such as nausea or dyspepsia, he was recommended intensive endoscopic surveillance and genetic counseling, considering the CDH1 mutation. For the esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) findings, any macroscopically significant lesion suggesting DGC was not observed in the individual's stomach. In addition, chronic active H. pylori gastritis was found. An endoscopic biopsy was performed by randomly selecting two sites, including lower and higher parts on the greater curvature of the stomach, but the results showed no abnormal pathological findings.

We informed the individual underwent genetic counseling along with his family members of the possibilities of their mutation status and of their options following the testing. Not all the family members underwent the genetic testing; the individual's older brother was found to have the same CDH1 mutation, identified in our individual. Therefore, they can be considered asymptomatic CDH1 mutation carriers; they received an explanation on the prophylactic gastrectomy, and then chose to opt for periodic surveillance. Under the surveillance program for screening CDH1 mutation-positive individuals in our genetic clinics, he and his older brother have annually undergone EGD to ensure that there is no evidence of clinically significant lesions. As of the time of this publication, they are alive and do not show the occurrence of GC, as ascertained by annual endoscopic surveillance for about 5 yr from the time of identification in CDH1 mutation.

CDH1, which is a known tumor suppressor gene, is located on chromosome 16q22.1, and it contains 2.6 kb of coding sequences and 16 exons. To date, approximately 122 CDH1 germline mutations have been identified [9]. Male and female carriers of a germline CDH1 mutation have over 80% of lifetime risk of developing DGC, along with a 33-52% increased risk of lobular breast cancer in women [10, 11].

In the present study, we identified c.1018A>G (p.Thr340Ala) located in CDH1, which is a known disease-causing mutation as reported in HDGC families in Europe and China [8, 12]. In Korea, there have been no previous reports to our knowledge on the identification of c.1018A>G in a GC-afflicted family, although it has been reported in two patients with ascending colon cancer and sigmoid colon cancer [13]. The functional analysis of the CDH1 mutation p.Thr340Ala showed that p.Thr340Ala-expressing cells exhibited altered cellular morphology from epithelial to fibroblastic morphotype and presented a highly motile phenotype [14]. In particular, p.Thr340Ala mutation influences cell migration by increasing Rho-GTPase activity [14].

CDH1-mutation positive individuals must be surveilled and be given genetic counseling [7]. The consensus reached at an IGCLC workshop was that individuals who test positive for a CDH1 mutation should be advised to consider prophylactic gastrectomy regardless of any endoscopic findings [5, 7]. If individuals with CDH1 mutation refuse or delay gastrectomy due to choice, surveillance endoscopy should be offered annually in order to ensure that there is no evidence of clinically significant lesions [7].

CDH1 mutations preferentially affect gastric epithelia, but tumors do occur outside the stomach in HDGC families, at sites including the colon, lung, prostate, salivary glands, pancreas, and appendix [15, 16]. Several studies have documented that colorectal cancer is an occasional member of the HDGC disease spectrum [15, 16, 17], with the recommendation that surveillance colonoscopy should commence in such families for individuals over the age of 40, or those who are 10 yr younger than the youngest person diagnosed with colon cancer [7]. However, the spectrum and frequency of other extra-gastric diseases occurring in in conjunction with HDGC is uncertain, mainly because the number of identified HDGC families is too small to establish significant associations [15]. Further studies are needed to accurately define such extra-gastric malignancies as being a part of the HDGC spectrum of malignancies in individuals with genetically verified HDGC, and to better define the clinical guidelines for screening the malignancies.

The lack of a sensitive screening test for HDGC makes its early diagnosis challenging. However, genetic testing can confirm whether a condition in patient is the result of an inherited syndrome. The identification of CDH1 mutation in individuals with a family history of GC may provide valuable information for genetic counseling, genetic testing for GC susceptibility, GC risk reduction management for the as-yet unaffected family members, and confirmatory diagnosis of HDGC for the proband [18]. Moreover, as more individuals with HDGC are identified early by genetic screening and undergo prophylactic gastrectomy, longer survival outcomes will effectively unveil additional risks of malignancy at other organ sites [16, 18]. However, there is a paucity of research on familial GC, and the effort to identify genetic causes in patients with GC is still unfamiliar to Korean clinicians, with the high prevalence of the GC in Korea making it undesirable [19, 20].

To summarize, clinicians should consider the relevance of genetic predisposition with early-onset or familial clustering of GC, irrespective of endoscopic findings showing abnormal gastric mucosa. A proactive attempt to identify familial GC, including genetic counseling and CDH1 screening, will provide comprehensive management and confirmatory diagnosis of HDGC, in addition to providing new insights into tumor initiation, progression, and metastasis of hereditary GC in Korea.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the Korea Health Technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (A120030).

Go to :

References

1. Vogelaar IP, van der Post RS, Bisseling TM, van Krieken JH, Ligtenberg MJ, Hoogerbrugge N. Familial gastric cancer: detection of a hereditary cause helps to understand its etiology. Hered Cancer Clin Pract. 2012; 10:18.

2. Jung KW, Won YJ, Kong HJ, Oh CM, Seo HG, Lee JS. Prediction of cancer incidence and mortality in Korea, 2013. Cancer Res Treat. 2013; 45:15–21.

5. Fujita H, Lennerz JK, Chung DC, Patel D, Deshpande V, Yoon SS, et al. Endoscopic surveillance of patients with hereditary diffuse gastric cancer: biopsy recommendations after topographic distribution of cancer foci in a series of 10 CDH1-mutated gastrectomies. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012; 36:1709–1717. PMID: 23073328.

6. Hu B, El Hajj N, Sittler S, Lammert N, Barnes R, Meloni-Ehrig A. Gastric cancer: Classification, histology and application of molecular pathology. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2012; 3:251–261. PMID: 22943016.

7. Fitzgerald RC, Hardwick R, Huntsman D, Carneiro F, Guilford P, Blair V, et al. Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer: updated consensus guidelines for clinical management and directions for future research. J Med Genet. 2010; 47:436–444.

8. Oliveira C, Bordin MC, Grehan N, Huntsman D, Suriano G, Machado JC, et al. Screening E-cadherin in gastric cancer families reveals germline mutations only in hereditary diffuse gastric cancer kindred. Hum Mutat. 2002; 19:510–517.

9. Corso G, Marrelli D, Pascale V, Vindigni C, Roviello F. Frequency of CDH1 germline mutations in gastric carcinoma coming from high- and low-risk areas: metanalysis and systematic review of the literature. BMC Cancer. 2012; 12:8.

10. Pharoah PD, Guilford P, Caldas C. International Gastric Cancer Linkage Consortium. Incidence of gastric cancer and breast cancer in CDH1 (E-cadherin) mutation carriers from hereditary diffuse gastric cancer families. Gastroenterology. 2001; 121:1348–1353.

11. Kaurah P, MacMillan A, Boyd N, Senz J, De Luca A, Chun N, et al. Founder and recurrent CDH1 mutations in families with hereditary diffuse gastric cancer. JAMA. 2007; 297:2360–2372.

12. Zhang Y, Liu X, Fan Y, Ding J, Xu A, Zhou X, et al. Germline mutations and polymorphic variants in MMR, E-cadherin and MYH genes associated with familial gastric cancer in Jiangsu of China. Int J Cancer. 2006; 119:2592–2596.

13. Kim HC, Wheeler JM, Kim JC, Ilyas M, Beck NE, Kim BS, et al. The E-cadherin gene (CDH1) variants T340A and L599V in gastric and colorectal cancer patients in Korea. Gut. 2000; 47:262–267.

14. Suriano G, Oliveira MJ, Huntsman D, Mateus AR, Ferreira P, Casares F, et al. E-cadherin germline missense mutations and cell phenotype: evidence for the independence of cell invasion on the motile capabilities of the cells. Hum Mol Genet. 2003; 12:3007–3016.

15. More H, Humar B, Weber W, Ward R, Christian A, Lintott C, et al. Identification of seven novel germline mutations in the human E-cadherin (CDH1) gene. Hum Mutat. 2007; 28:203.

16. Hamilton LE, Jones K, Church N, Medlicott S. Synchronous appendiceal and intramucosal gastric signet ring cell carcinomas in an individual with CDH1-associated hereditary diffuse gastric carcinoma: a case report of a novel association and review of the literature. BMC Gastroenterol. 2013; 13:114.

17. Blair V, Martin I, Shaw D, Winship I, Kerr D, Arnold J, et al. Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer: diagnosis and management. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006; 4:262–275.

18. Chen Y, Kingham K, Ford JM, Rosing J, Van Dam J, Jeffrey RB, et al. A prospective study of total gastrectomy for CDH1-positive hereditary diffuse gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011; 18:2594–2598.

19. Kim S, Chung JW, Jeong TD, Park YS, Lee JH, Ahn JY, et al. Searching for E-cadherin gene mutations in early onset diffuse gastric cancer and hereditary diffuse gastric cancer in Korean patients. Fam Cancer. 2013; 12:503–507.

20. Kim S, Ki CS, Kim KM, Lee MG, Kim S, Bae JM, et al. Novel mechanism of a CDH1 splicing mutation in a Korean patient with signet ring cell carcinoma. BMB Rep. 2011; 44:725–729. PMID: 22118538.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download