Dear Editor,

Coagulation factor XI (FXI) is a member of the "contact pathway" and is activated either intrinsically by coagulation factor XII (FXII) or by thrombin, which is produced by an extrinsic pathway and plays an important role in hemostasis [1]. Factor XI deficiency, also known as hemophilia C, is a predominantly autosomal recessive genetic bleeding disorder that was first reported in 1953 [2] and was found to be particularly prevalent in the Ashkenazi Jewish population [3]. The main clinical manifestation is damage-related or post-operational bleeding in the buccal cavity, nasal cavity, tonsils, or urinary tract [4]. The F11 gene encodes the FXI protein, and mutations in the F11 gene have been found in patients with FXI deficiency. The F11 gene, located on the long arm of chromosome 4 (4q35) with a genome size of 23 kb, consists of 15 exons and 14 introns [5]. Exon 1 encodes the 5'-untranslated region, exon 2 encodes the signal peptide, and exons 3-15 are the region for encoding factor FXI protein [6]. FXI is synthesized as a homodimeric protein, and each FXI monomer consists of 4 N-terminal "apple domains" (A1-A4) and a C-terminal trypsin-like catalytic domain.

According to the F11 gene mutation database (http://www.factorxi.org), 192 mutations are associated with FXI deficiency. While the F283L missense mutation and the E117X nonsense mutation predominate in Ashkenazi Jews [7, 8], additional mutations have been reported in the non-Jewish populations. For example, the C38R missense mutation has been found to have a relatively high frequency in French Basques [9], whereas the C128X and Q88X nonsense mutations are more frequently reported in English Caucasians and in families from Western France, respectively [10, 11]. The fact that some mutations, such as F283L and E117X, predominate in one population (i.e., the Ashkenazi Jewish population) but have never been found in others (i.e., Asian populations) indicates that they are likely to be founder mutations. Although large-scale population studies have not been carried out in a specific Asian population, smaller-scale studies have shown the prevalence of two nonsense mutations (Q226X and Q263X) in Japanese [12], Chinese [13], and Korean [14] patients. In this letter, we report the first case of a heterozygous mutation (C482W) in the F11 gene, resulting in a mild FXI deficiency in a Korean patient.

A 14-yr-old male patient with intermittent epistaxis was admitted to the hospital because of increased epistaxis frequency and excessive blood flow. The patient did not have any abnormal medical history that would have indicated bleeding tendency, apart from being treated for allergic rhinitis. On admission, his vital signs were normal and the initial systemic examination did not uncover any bleeding problem or any other significant problem to be reported. The blood test results were as follows: leukocyte count, 5.6×109/L; hemoglobin level, 15.9 g/dL; and platelet count, 215×109/L. The blood coagulation test showed normal prothrombin time (PT; 12.0 sec; reference range, 9.9-12.3 sec) but prolonged activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT; 45.9 sec, reference range, 20.9-35.0 sec). The thrombin time was normal (16.3 sec; reference range, 14.0-18.3 sec). When the patient's plasma sample was mixed with the normal plasma sample (ratio 1:1), the prolonged aPTT was corrected to within the normal range. The level of von Willebrand factor was within the reference range. The lupus anticoagulant test results were negative. The activity levels of factors II through XII were within the reference ranges, whereas FXI showed slightly decreased activity (26%; reference range, 60-140%).

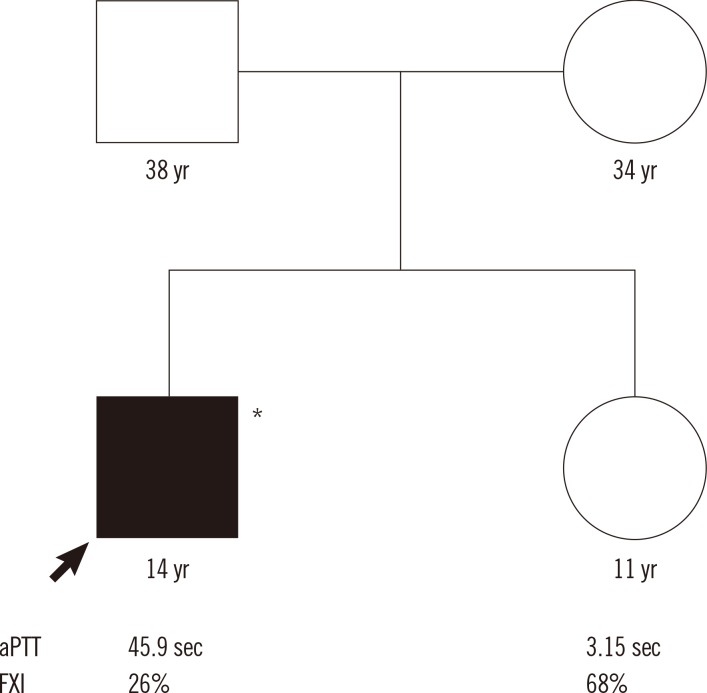

The patient has an 11-yr-old sister who had no symptoms and no abnormal test results for the above described tests. The patient's parents did not consent to be tested. The pedigree of the patient is shown in Fig. 1. Consent was obtained from the patient's mother for the parent's molecular genetic testing, and a whole blood sample was collected. The patient's genomic DNA was extracted from the collected whole blood sample by using the Easy-DNA Kit (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Exons 7, 8, 11, and 13 of the F11 gene were amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with the previously designed primer sets [14]. Direct sequencing of the amplified regions was performed by using the ABI Prism 3500dx automated genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), the same primers that were used to amplify the 4 exons of the F11 gene by PCR, and the Big Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction Kit (Applied Biosystems). Sequencher software (Gene Codes Corporation, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) was used to compare the patient's DNA sequences to the reference DNA sequence (GenBank accession number, NM_000128.3). The guidelines of the Human Genome Variation Society (HGVS) were used to identify the sequence variations.

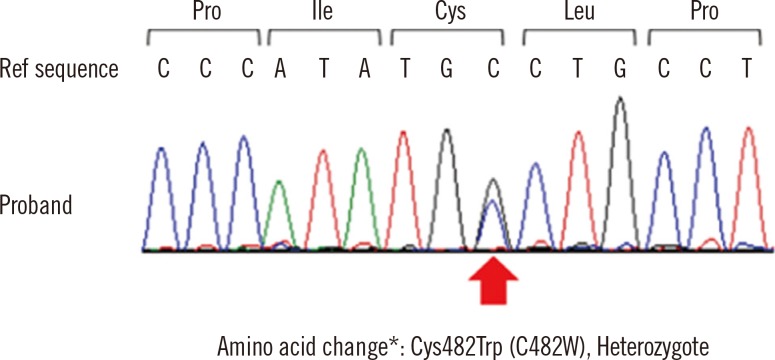

A heterozygous cytosine-to-guanine substitution, located at nucleotide 1,500 on exon 13, was identified in the patient's F11 gene. This mutation resulted in a cysteine-to-tryptophan amino acid change at codon 500 (p.Cys500Trp, according to HGVS nomenclature or Cys482Trp, according to the nomenclature suggested by Asakai et al. [6] (Fig. 2). Hereafter, we have used the conventional nomenclature method suggested by Asakai et al. [6] to refer to the identified amino acid change (Cys482Trp).

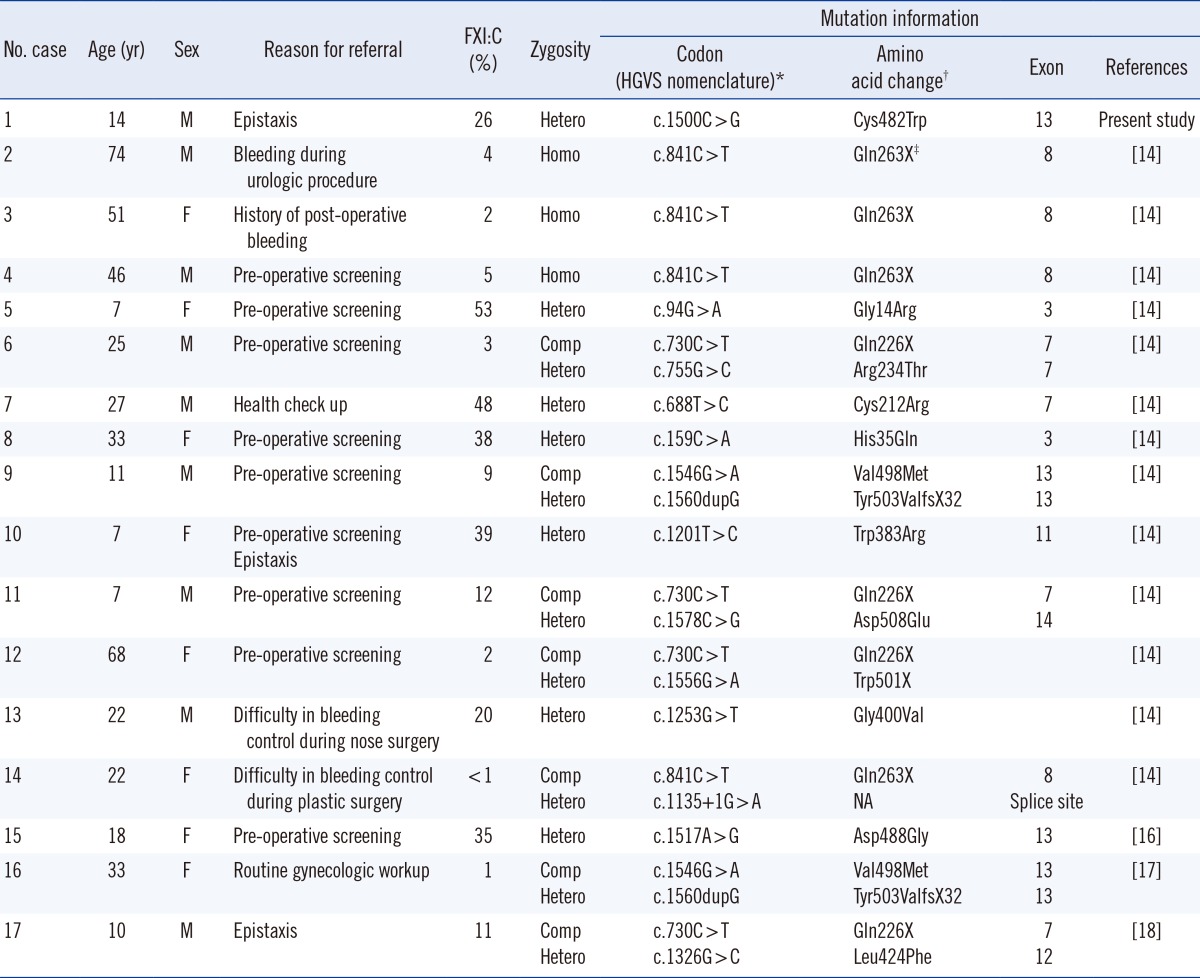

The Cys482Trp missense mutation identified in our patient was previously reported in England [15], but has never been reported in Korea. Only 17 cases of FXI deficiency (including the present case) have been confirmed by molecular and genetic testing in Korea [14, 16, 17, 18] (Table 1). Therefore, further testing and discovery of molecular lesions in the F11 gene in the Korean patients with FXI deficiency is needed to gain better understanding of founder mutations that are specific to this population. Such studies would facilitate the development of a database in order to better identify mutations in Korea and their relationship with racial and geographical differences.

Patients with FXI deficiency show a wide spectrum of bleeding severity. Patients with severe symptoms (FXI activity <20%) are either homozygotes or complex heterozygotes, while those with heterozygous mutations usually show no or only minor symptoms [4]. The present patient did not have epistaxis, except when the allergic rhinitis worsened, and the blood coagulation test results were normal except for the prolonged aPTT. The patient was found to be a carrier for a mutation that results in a non-synonymous amino acid change (Cys482Trp). This mutation affects exon 13, which encodes the FXI C-terminal serine protease (SP) domain that is important for dissociating the disulfide bond between the Cys482 and Cys362 residues. This dissociation is followed by a change in conformation and reduction in the activation of FXI [15].

The F11 gene, located on chromosome 4, consists of 15 exons and 14 introns and spans 23 kb [5]. To date, the genetic tests that have been performed in the Korean patients with FXI deficiency were conducted by testing all 15 exons to identify mutations. However, in this case, only four exons (7, 8, 11, and 13) were subjected to sequencing. Since the Q226X and Q263X nonsense mutations commonly occur in the Korean patients with FXI deficiency. Kim et al. [14] proposed that these patients should first be screened for putative mutations affecting exons 7 and 8. Their study showed that 57.1% of patients had mutations in exons 7 and 8, with the detection rate increasing to 71.4% when exon 13 was included, and to 80.1% when exon 11 was also included. In addition, all the other reported cases where the molecular bases of the FXI deficiency were confirmed in the Korean patients were found to be mutations affecting either exon 7 [18] or exon 13 [16, 17]. Thus, these findings strongly indicate that identification of causative mutations in the Korean patients with FXI deficiency should involve initial screening of mutations in exons 7, 8, 11, and 13 by sequencing. Sequencing of the additional 11 exons is warranted, if the screening results for those 4 exons are not in line with the patient's clinical manifestation. Furthermore, it would also be efficient in terms of time and cost to screen the other exons as well when the clinical manifestation is very severe (i.e., FXI activity is severely reduced), which indicates a homozygous or complex heterozygous mutation, but only a single heterozygous mutation is identified in one of the four most frequently mutated exons. In this case, further screening was not needed since the patient's mild clinical manifestation and FXI coagulation test results were in agreement with the finding that the patient was heterozygous for a mutation affecting exon 13.

In summary, we identified the Cys482Trp missense mutation in a Korean patient with FXI deficiency. Owing to the small number of FXI deficiency cases with associated mutations that have been reported in Korea to date, further studies are warranted to contribute to the development of a database that would help clarify the distribution of mutations present in the Korean population. Such a database would also facilitate studies aimed to clarify the possibility of a founder effect for F11 gene mutations. Furthermore, these efforts would help improve the molecular and genetic diagnostic strategies used for the Korean patients.

References

1. Seligsohn U. Factor XI in haemostasis and thrombosis: past, present and future. Thromb Haemost. 2007; 98:84–89. PMID: 17597996.

2. Rosenthal RL, Dreskin OH, Rosenthal N. New hemophilia-like disease caused by deficiency of a third plasma thromboplastin factor. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1953; 82:171–174. PMID: 13037836.

3. Seligsohn U. High gene frequency of factor XI (PTA) deficiency in Ashkenazi Jews. Blood. 1978; 51:1223–1228. PMID: 647126.

4. Seligsohn U. Factor XI deficiency in humans. J Thromb Haemost. 2009; 7(Suppl 1):84–87. PMID: 19630775.

5. Kato A, Asakai R, Davie EW, Aoki N. Factor XI gene (F11) is located on the distal end of the long arm of human chromosome 4. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1989; 52:77–78. PMID: 2612218.

6. Asakai R, Davie EW, Chung DW. Organization of the gene for human factor XI. Biochemistry. 1987; 26:7221–7228. PMID: 2827746.

7. Asakai R, Chung DW, Davie EW, Seligsohn U. Factor XI deficiency in Ashkenazi Jews in Israel. N Engl J Med. 1991; 325:153–158. PMID: 2052060.

8. Shpilberg O, Peretz H, Zivelin A, Yatuv R, Chetrit A, Kulka T, et al. One of the two common mutations causing factor XI deficiency in Ashkenazi Jews (type II) is also prevalent in Iraqi Jews, who represent the ancient gene pool of Jews. Blood. 1995; 85:429–432. PMID: 7811996.

9. Zivelin A, Bauduer F, Ducout L, Peretz H, Rosenberg N, Yatuv R, et al. Factor XI deficiency in French Basques is caused predominantly by an ancestral Cys38Arg mutation in the factor XI gene. Blood. 2002; 99:2448–2454. PMID: 11895778.

10. Bolton-Maggs PH, Peretz H, Butler R, Mountford R, Keeney S, Zacharski L, et al. A common ancestral mutation (C128X) occurring in 11 non-Jewish families from the UK with factor XI deficiency. J Thromb Haemost. 2004; 2:918–924. PMID: 15140127.

11. Quélin F, Trossaert M, Sigaud M, Mazancourt PD, Fressinaud E. Molecular basis of severe factor XI deficiency in seven families from the west of France. Seven novel mutations, including an ancient Q88X mutation. J Thromb Haemost. 2004; 2:71–76. PMID: 14717969.

12. Okumura K, Kyotani M, Kawai R, Takagi A, Murate T, Yamamoto K, et al. Recurrent mutations of factor XI gene in Japanese. Int J Hematol. 2006; 83:462–463. PMID: 16787881.

13. Wang J, Wang X, Dai J, Ding Q, Fu Q, Wang H, et al. A case of factor XI deficiency caused by compound heterozygous F11 gene mutation. Haemophilia. 2009; 15:603–606. PMID: 19347998.

14. Kim J, Song J, Lyu CJ, Kim YR, Oh SH, Choi YC, et al. Population-specific spectrum of the F11 mutations in Koreans: evidence for a founder effect. Clin Genet. 2012; 82:180–186. PMID: 21668437.

15. Mitchell M, Mountford R, Butler R, Alhaq A, Dai L, Savidge G, et al. Spectrum of factor XI (F11) mutations in the UK population--116 index cases and 140 mutations. Hum Mutat. 2006; 27:829. PMID: 16835901.

16. Lee JH, Cho HS, Hyun MS, Kim HY, Kim HJ. A novel missense mutation Asp506Gly in Exon 13 of the F11 gene in an asymptomatic Korean woman with mild factor XI deficiency. Korean J Lab Med. 2011; 31:290–293. PMID: 22016685.

17. Kwon MJ, Kim HJ, Bang SH, Kim SH. Severe factor XI deficiency in a Korean woman with a novel missense mutation (Val498Met) and duplication G mutation in exon 13 of the F11 gene. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2008; 19:679–683. PMID: 18832909.

18. Kim J, Kim Y, Shin S, Lyu CJ, Choi JR, Lee KA. A novel F11 mutation in a Korean pediatric patient with recurrent epistaxis. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2013; 24:433–435. PMID: 23187786.

Fig. 1

Pedigree of the family with factor XI deficiency. Genetic analysis was available for one family member (*).

Abbreviations: aPTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; FXI, factor XI activity level.

Fig. 2

Identification of the F11 gene mutation. Direct sequencing of the proband demonstrated a heterozygous mutation, c.1500C >G, (p.Cys500Trp [Cys482Trp]) of exon 13 in the F11 gene. The location of the variation is indicated by an arrow. *Conventional numbering according to Asakai et al. [6] at the protein level, omitting the signal peptide and counting the start codon ATG as -18.

Abbreviation: Ref sequence, reference DNA sequence.

Table 1

Phenotypic and genotypic results in the Korean patients with FXI deficiency

*The approved HGVS nomenclature with 'A' of the translation initiation codon ATG numbered as +1 was used to describe nucleotide numbering for coding level; †Conventional numbering according to Asakai et al. [6] at the protein level, omitting the signal peptide and counting the start codon ATG as -18; ‡X in this column indicates the stop codon.

Abbreviations: Comp Hetero, compound heterozygote; Hetero, heterozygote; HGVS, Human Genome Variation Society; Homo, homozygote; F, female; FXI, factor XI; FXI:C, FXI coagulant activity; M, male; NA, not available.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download