Abstract

Background

Concerns regarding increasing microbial resistance to vancomycin have resulted in recommendations for a higher trough serum vancomycin concentration. This study aimed to assess the dosage guidelines targeting vancomycin trough concentrations of 15-20 mg/L.

Methods

About 216 adult patients (age, >60 yr) were treated with intravenous vancomycin. The patients were divided into 2 groups according to their target vancomycin trough concentrations: the previous guideline group (n=108) treated with targeted vancomycin trough concentrations of 5-15 mg/L from Jan 2009 through April 2011 and the new guideline group (n=108) treated with targeted concentrations of 15-20 mg/L from November 2011 through July 2012.

Results

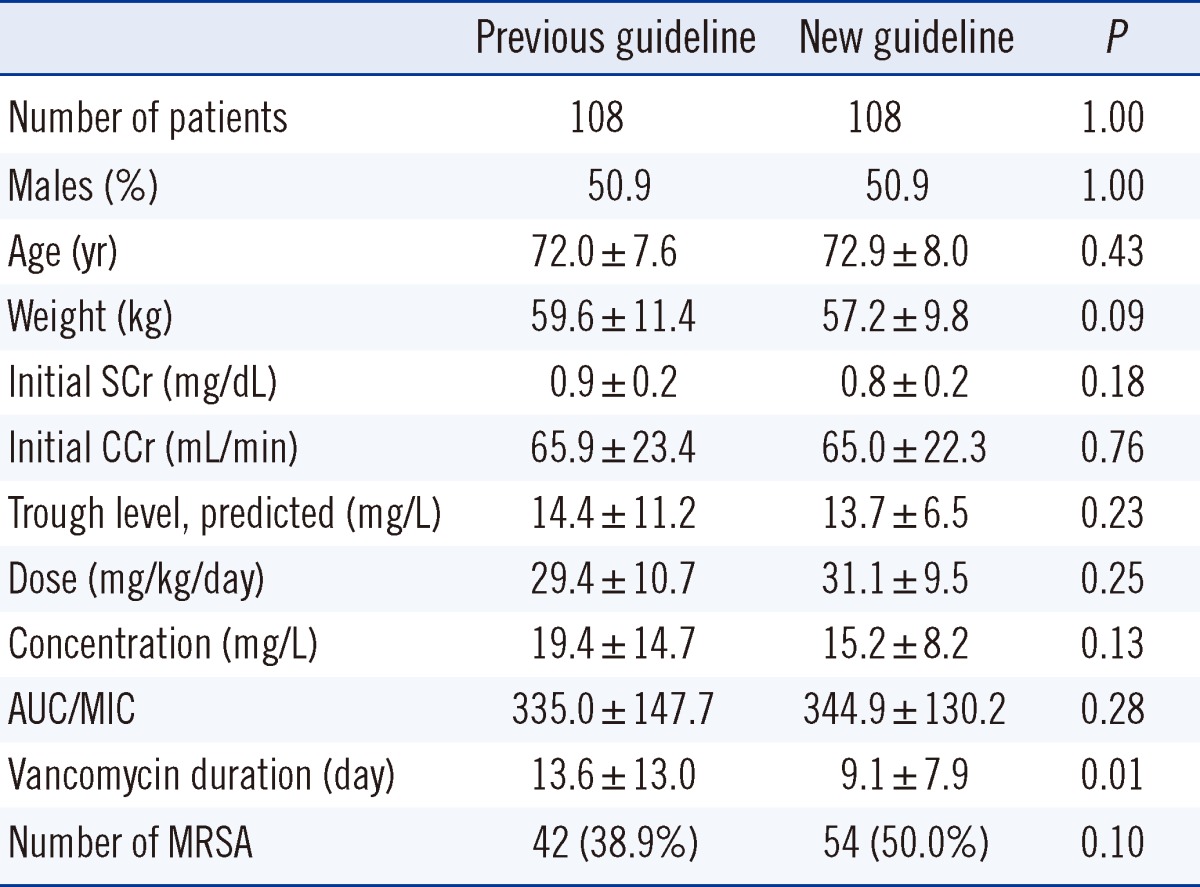

The 2 groups were not significantly different with respect to age, weight, initial serum creatinine, initial creatinine clearance, predictive trough levels, doses, serum drug concentrations, and area under the curve/minimal inhibitory concentrations. Regarding the proportions of vancomycin trough concentrations, the target range was achieved in 50% in the previous guideline group and in 16% in the new guideline group. In the previous and new guideline groups, the trough concentrations of 10-20 mg/dL were observed in 32.4% and 52.8% patients, respectively, and those of <10 mg/L were observed in 45.4% and 29.6%, respectively.

Conclusions

Compared to the previous guideline group, the new guideline group showed higher proportions in the therapeutic range of 10-20 mg/L and lower proportions in trough concentrations <10 mg/L. The strictly managed vancomycin therapeutic drug monitoring in the new guideline group was assessed as more effective.

Vancomycin is a glycopeptide antibiotic that has been in clinical use for nearly 50 yr as an alternative to penicillin to treat penicillinase-producing strains of Staphylococcus aureus [1, 2]. It is one of the most widely used antibiotics in the United States for the treatment of serious gram-positive infections involving methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) [3, 4]. Despite limitations such as poor tissue penetration, relatively slow antibacterial effects, and the potential for toxicity, vancomycin is regarded as the gold standard for antibiotic treatment of MRSA infections because of its low cost and established clinical response [5, 6].

With the rapid increase in microbial resistance and concerns about the clinical consequences of underdosing, the efficient achievement of target concentrations of vancomycin has become increasingly important. Traditionally, "peak" and "trough" concentrations were measured and the focus was on preventing toxicity by avoiding what were perceived to be excessive troughs [7, 8]. However, the monitoring of peak serum vancomycin concentrations is no longer recommended because this does not decrease the frequency of nephrotoxicity and the concentrations do not correlate with ototoxicity [9]. According to this approach, revised vancomycin recommendations for adults were released in 2009 [9]. On the basis of this guideline, trough serum vancomycin concentrations are the most accurate and practical method for monitoring vancomycin effectiveness. These recommendations discuss the need for more aggressive dosing and higher troughs based on the type of infection. Higher trough serum concentrations of 15-20 mg/L are now recommended for the following severe diseases: bacteremia, endocarditis, osteomyelitis, meningitis, and hospital-acquired pneumonia caused by MRSA [10].

The use of vancomycin is associated with a number of adverse effects, including infusion-related toxicities, nephrotoxicity, and possible ototoxicity. Because the primary route of vancomycin elimination is via renal excretion, the vancomycin dose must be adjusted depending on the patient's renal function. Vancomycin should be used with caution in elderly patients, because increasing age is associated with a progressive decrease in the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) [11]. Thus, adjusting the doses of vancomycin is important in elderly patients. This study aimed to assess the dosage guidelines targeting vancomycin trough concentrations of 15-20 mg/L in elderly patients.

A total of 216 adult patients over 60 yr of age with normal renal function, who had been treated with intravenous vancomycin at Ewha Womans University Mokdong Hospital, were evaluated for dosing and pharmacokinetic parameters in this retrospective chart review. These patients had various diseases, including pneumonia, wound infection, and surgical site infection. These patients were divided into 2 groups: the previous guideline group and the new guideline group. The previous guideline group comprised 108 adults who were treated from January 2009 through April 2011 with a target vancomycin trough concentration of 5-15 mg/L, and the new guideline group comprised 108 adults who were treated from November 2011 through July 2012 with a target concentration of 15-20 mg/L. Severe diseases (bacteremia, endocarditis, osteomyelitis, meningitis, and hospital-acquired pneumonia caused by MRSA) were found in 13.0% patients (14/108) in the previous guideline group and in 13.9% (15/108) in the new guideline group. Table 1 provides patient demographics, vancomycin dosage, and concentration data. The 2 groups did not differ significantly with respect to age, weight, initial serum creatinine, initial creatinine clearance, predictive trough levels, doses, serum drug concentrations, AUC/MIC, and the presence of MRSA. MRSA, methicillin-sensitive S. aureus (MSSA), coagulase-negative Staphylococcus, and Enterococci were found in 38.9% (42/108), 2.8% (3/108), 12.0% (13/108), and 1.9% (2/108), respectively, in the previous guideline group and in 50.0% (54/108), 0.9% (1/108), 15.7% (17/108), and 4.6% (5/108), respectively, in the new guideline group (data not shown).

The vancomycin drug concentrations were analyzed by Architect iVancomycin (Abbott, Wiesbaden, Germany) using the Architect i1000 SR analyzer (Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL, USA). Architect iVancomycin is an in vitro chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay (CMIA) for the quantitative measurement of vancomycin in human serum or plasma. The analytical measurement range (AMR) of the Architect iVancomycin assay was 0.24 µg/mL to 100 µg/mL and the clinical reportable range (CRR) of the Architect iVancomycin assay was 0.5 µg/mL to 80 µg/mL. The inter-assay coefficients of variation were 10% at 8.2 mg/L, 10% at 24.2 mg/L, and 9% at 42.0 mg/L.

The serum vancomycin predictive trough concentrations were calculated by using Abbott's PKS software program. The following clinical factors were investigated for their influences on the pharmacokinetics of vancomycin: gender, age, height (cm), weight (kg), serum creatinine (mg/dL), serum albumin (g/dL), vancomycin dose (mg/kg/day), vancomycin concentration (mg/L), and days of therapy.

A data file containing all clinical, dosage, and concentration data recorded for patients in the evaluation dataset was created. Individual estimates of vancomycin pharmacokinetic parameters were then obtained for each patient by Bayesian analysis using Abbott's PKS software program. The area under the curve (AUC) was calculated from the daily dose amount (mg/day)/[(creatinine clearance×0.79)+15.4]/0.06 [7]. The creatinine clearance was calculated by using the Cockcroft.Gault formula, (140-age)×weight (kg)×(0.85 if female)/serum creatinine (mg/dL)/72. The minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of vancomycin was measured using the VITEK 2 Compact Microbial Identification System (bioMerieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France).

The reference range of the laboratory target vancomycin trough concentration changed from 5-15 mg/L to 15-20 mg/L after October 2011.

The 216 patients were divided into 2 groups, the previous guideline group and the new guideline group, and these groups of patients were compared. The Chi-square test or Fisher's exact test was used for categorical variables and the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney U test was used for continuous variables. All P values were considered significant at P≤0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 18.0 for windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

The data were compared between the 2 groups to evaluate the association between the presence of kidney toxicity and severe disease. Kidney toxicity was defined as an increase of >0.5 mg/dL (or a ≥50% increase) in serum creatinine over baseline in consecutively obtained daily serum creatinine values. Kidney toxicity was found in 6.5% (7/108) of the previous guideline group and in 11.1% (12/108) of the new guideline group, and severe diseases were found in 13.0% (14/108) of the previous guideline group and in 13.9% (15/108) of the new guideline group. Kidney toxicity and disease severity did not differ between the 2 groups (P=0.23 and P=0.84, respectively).

The AUC/MIC above 400 was 73.1% (79/108) in the previous guideline group and 71.3% (77/108) in the new guideline group. The proportions above 400 for AUC/MIC were not different between the 2 groups (P=0.761).

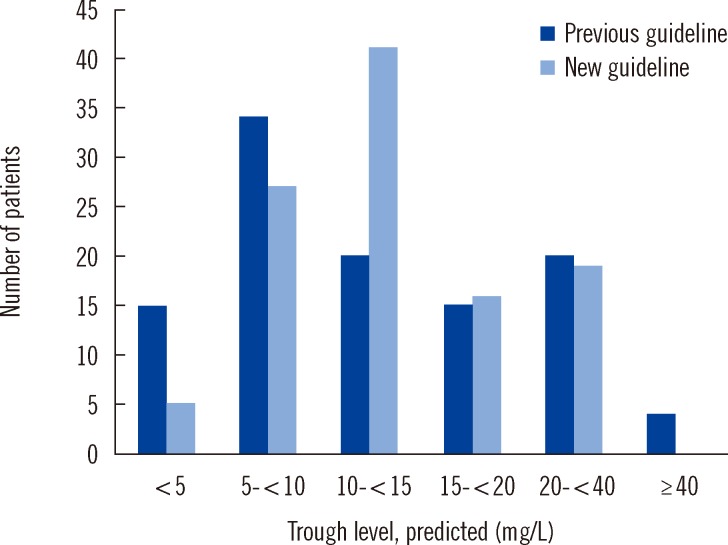

The percentages of patients in whom the target vancomycin trough concentrations comprised the target ranges in the previous and new guideline groups were 50% (54/108) and 14.8% (16/108), respectively. The percentage of patients with trough concentrations of 10-20 mg/dL was 32.4% (35/108) in the previous guideline group and 52.8% (57/108) in the new guideline group, and the percentage of patients in whom it was <10 mg/L was 45.4% (49/108) and 29.6% (32/108), respectively, (P=0.004) (Fig. 1).

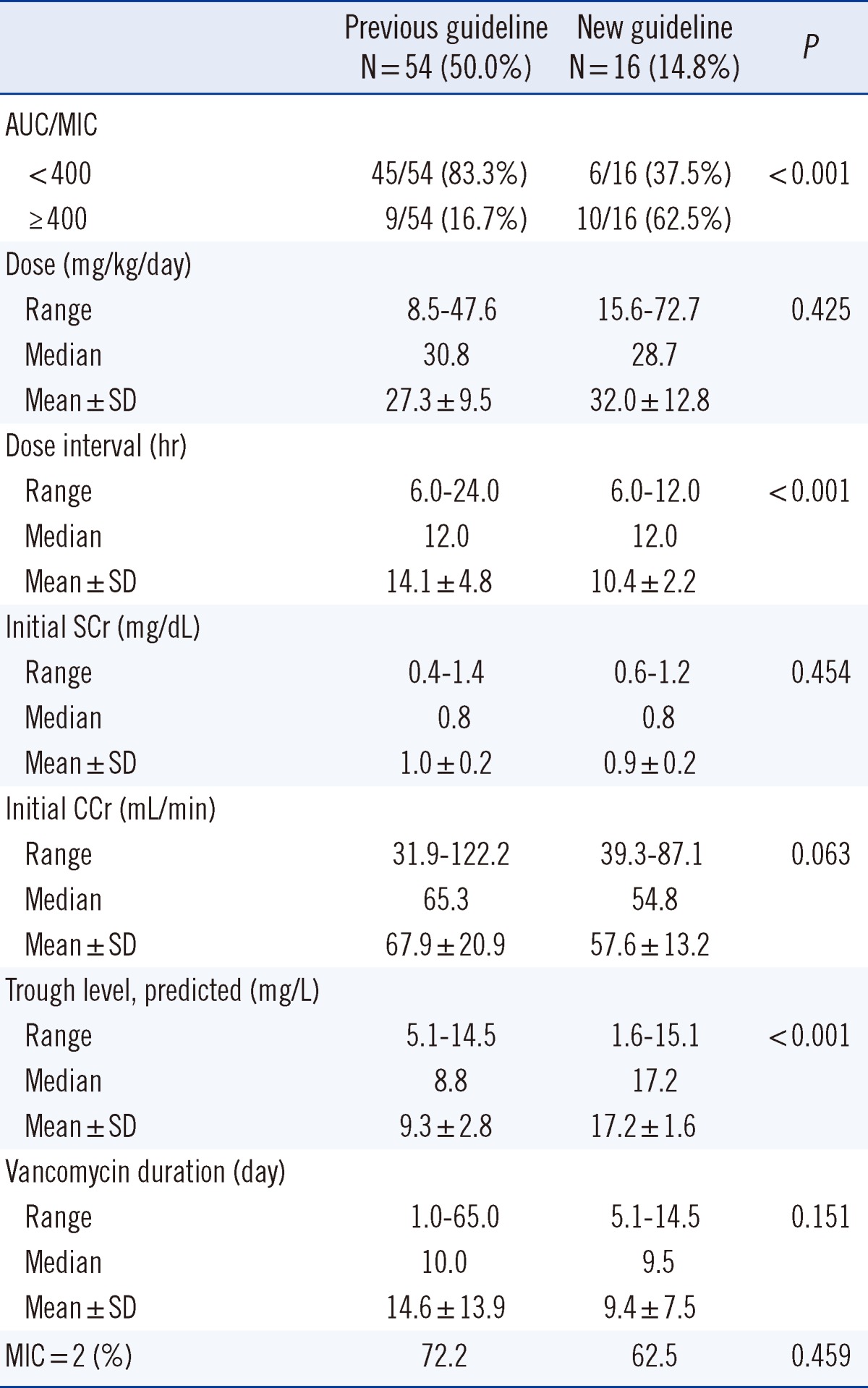

The percentages of patients in whom the target vancomycin trough concentrations comprised the target ranges in the previous and new guideline groups were 50% (54/108) and 14.8% (16/108), respectively (Table 2). All further analyses described in this section were conducted in the patients, in whom these target ranges were achieved. Analysis of these patients revealed that the AUC/MIC over 400 was observed in 16.7% (9/54) in the previous guideline group and in 62.5% (10/16) in the new guideline group (P<0.001). The mean dose was 27.3±9.5 mg/kg/day and 32.0±12.8 mg/kg/day in the previous and new guideline groups, respectively, without significant difference (P=0.425); however, the dose interval was shorter in the new guideline group (14.1±4.8 hr vs. 10.4±2.2 hr) (P<0.001). Analysis of initial serum creatinine levels revealed that the mean level was 1.0±0.2 mg/dL and 0.9±0.2 mg/dL in the previous and in the new guideline group, respectively (P=0.454). Further, the mean initial creatinine clearance level was 67.9±20.9 mL/min in the previous guideline group and 57.6±13.2 mL/min in the new guideline group (P=0.063). The predictive trough level was higher in the new guideline group (9.3±2.8 mg/L vs. 17.2±1.6 mg/L) (P<0.001), whereas the vancomycin duration was not significantly different between the 2 groups (14.6±13.9 days in the previous guideline group vs. 9.4±7.5 days in the new guideline group, P=0.151). The proportion of patients with MIC=2 was 72.2% (39/54) in the previous guideline group and 62.5% (10/16) in the new guideline group (P=0.459). Analysis of our data yielded the following predictive equation: trough concentration=8.662+0.086×dose, r=0.213, P=0.077.

In this study, we investigated the relationship between vancomycin trough concentrations and several therapeutic drug-monitoring (TDM) parameters in 216 elderly patients with normal renal function. This study used data collected during routine TDM to determine population estimates of vancomycin pharmacokinetic parameters, to develop new dosage guidelines, and to evaluate these new guidelines prospectively.

Vancomycin has been used as the primary therapeutic agent to treat MRSA infections for the past 50 yr [1-3]. Until recently, vancomycin was usually administered intravenously to adults at a dosage of 1,000 mg every 12 hr, with the targeted serum trough level between 5 and 10 mg/L [12, 13]. Recently, the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP), the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), and the Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists (SIDP) advised that vancomycin should be given in doses sufficient to achieve a trough level between 15 to 20 mg/L for the treatment of MRSA. Further, the British National Formulary (BNF) recommendation for intravenous pulsed infusion of vancomycin has recently been changed to 1,000-1,500 mg twice daily, and this value is reduced to 500 mg twice daily or 1,000 mg daily in patients over 65 yr of age [14]. Daily doses of >2,000 mg are usually required for patients with normal renal function to achieve trough concentrations above 10 mg/L, particularly if they are critically ill [15, 16]. The optimal doses and trough levels of adults remain controversial because of the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of vancomycin [17], lack of well-designed randomized clinical evaluations, and lack of data to support a clear relationship between specific serum concentrations and patient outcome. The present study demonstrated that the new guidelines would achieve vancomycin trough concentrations of 15-20 mg/L earlier and more consistently than previous dosage guidelines.

In this study, the percentages of patients in whom the target vancomycin trough concentrations comprised the target ranges in the previous and new guideline groups were 50% and 14.8%, respectively. The percentage of patients in whom the trough concentration was 10-20 mg/dL was 32.4% in the previous guideline group and 52.8% in the new guideline group, and the percentage of patients in whom it was <10 mg/L was 45.4% and 29.6%, respectively. These findings indicate that the new guideline group tended to reach the ideal vancomycin trough concentration. Trough serum vancomycin concentrations of <10 mg/L may predict therapeutic failure and the potential for the emergence of vancomycin-intermediate S. aureus (VISA) or vancomycin-resistant S. aureus (VRSA) [18, 19].

The AUC/MIC robustly predicts treatment outcomes when treating MRSA infections with vancomycin, and an AUC/MIC ratio of ≥400 has been advocated as a target to achieve clinical effectiveness with vancomycin [9]. Vancomycin dosages of 15-20 mg/kg given every 8-12 hr are required for most adult patients with normal renal function to achieve the suggested serum concentrations when the MIC is ≤1 mg/L [9]. In the present study, 28.7% of patients were predicted to achieve a satisfactory AUC/MIC, if the new guidelines were followed. The proportions above 400 for the AUC/MIC were not significantly different between the 2 groups. However, when analyzing the patients who comprised the target ranges in each group, the percentage of patients in whom AUC/MIC over 400 was 16.7% in the previous guideline group and 62.5% in the new guideline group (P<0.001).

In this study, the dose intervals were expected to be more frequent and the predicted trough levels were higher in the new guideline group. Increased dosing will be required, if higher trough concentrations are necessary.

Analysis of our data yielded the following predictive equation regarding trough concentration and dose: trough concentration=8.662+0.086×dose, r=0.213, P=0.077. This predictive equation should be formally assessed for efficacy, safety, and outcome before being applied in clinical practice.

In conclusion, we have confirmed new vancomycin trough concentration guidelines by following a population analysis of routine vancomycin concentration data. We observed that the new guideline group was more likely, than the previous guideline group, to achieve a trough concentration in the therapeutic range of 10-20 mg/L and was less likely to achieve a trough concentration of <10 mg/L. Further, among patients in whom the target ranges were achieved in each group, the proportion of patients with AUC/MIC over 400 was greater in the new guideline group. The strict management of vancomycin TDM in the new guideline group appears to have been more effective. Further studies on clinical efficacy before increases in the target trough level are recommended.

References

1. Song YG, Kim HK, Roe EK, Lee SY, Ahn BS, Kim JH, et al. Therapeutic Drug Monitoring of Vancomycin in Korean Patients. Infect Chemother. 2004; 36:311–318.

2. MacGowan AP. Pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics, and therapeutic drug monitoring of glycopeptides. Ther Drug Monit. 1998; 20:473–477. PMID: 9780121.

3. Kim DI, Im MS, Choi JH, Lee J, Choi EH, Lee HJ. Therapeutic monitoring of vancomycin according to initial dosing regimen in pediatric patients. Korean J Pediatr. 2010; 53:1000–1005. PMID: 21253314.

4. Moellering RC Jr. Vancomycin: a 50-yr reassessment. Clin Infect Dis. 2006; 42(Suppl 1):S3–S4. PMID: 16323117.

5. Kollef MH. Limitations of vancomycin in the management of resistant staphylococcal infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2007; 45(Suppl 3):S191–S195. PMID: 17712746.

6. Patanwala AE, Norris CJ, Nix DE, Kopp BJ, Erstad BL. Vancomycin dosing for pneumonia in critically ill trauma patients. J Trauma. 2009; 67:802–804. PMID: 19820588.

7. Moise-Broder PA, Forrest A, Birmingham MC, Schentag JJ. Pharmacodynamics of vancomycin and other antimicrobials in patients with Staphylococcus aureus lower respiratory tract infections. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2004; 43:925–942. PMID: 15509186.

8. Tobin CM, Darville JM, Thomson AH, Sweeney G, Wilson JF, MacGowan AP, et al. Vancomycin therapeutic drug monitoring: is there a consensus view? The results of a UK National External Quality Assessment Scheme (UK NEQAS) for Antibiotic Assays questionnaire. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2002; 50:713–718. PMID: 12407128.

9. Rybak M, Lomaestro B, Rotschafer JC, Moellering R Jr, Craig W, Billeter M, et al. Therapeutic monitoring of vancomycin in adult patients: a consensus review of the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, the Infectious Diseases Society of America, and the Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2009; 66:82–98. PMID: 19106348.

10. Eiland LS, English TM, Eiland EH 3rd. Assessment of vancomycin dosing and subsequent serum concentrations in pediatric patients. Ann Pharmacother. 2011; 45:582–589. PMID: 21521865.

11. Verhave JC, Fesler P, Ribstein J, du Cailar G, Mimran A. Estimation of renal function in subjects with normal serum creatinine levels: influence of age and body mass index. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005; 46:233–241. PMID: 16112041.

12. Patanwala AE, Norris CJ, Nix DE, Kopp BJ, Erstad BL. Vancomycin dosing for pneumonia in critically ill trauma patients. J Trauma. 2009; 67:802–804. PMID: 19820588.

13. Cunha BA. Vancomycin revisited: a reappraisal of clinical use. Crit Care Clin. 2008; 24:393–420. PMID: 18361953.

14. Joint Formulary Committee. British National Formulary. 56th ed. London: British Medical Association and Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain;2008.

15. del Mar Fernández de Gatta Garcia M, Revilla N, Calvo MV, Domínguez-Gil A, Sánchez Navarro A. Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic analysis of vancomycin in ICU patients. Intensive Care Med. 2007; 33:279–285. PMID: 17165021.

16. Pea F, Porreca L, Baraldo M, Furlanut M. High vancomycin dosage regimens required by intensive care unit patients cotreated with drugs to improve haemodynamics following cardiac surgical procedures. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2000; 45:329–335. PMID: 10702552.

17. American Thoracic Society. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Guidelines for the management of adults with hospital-acquired, ventilator-associated, and healthcare-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005; 171:388–416. PMID: 15699079.

18. Sakoulas G, Gold HS, Cohen RA, Venkataraman L, Moellering RC, Eliopoulos GM. Effects of prolonged vancomycin administration on methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in a patient with recurrent bacteraemia. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2006; 57:699–704. PMID: 16464892.

19. Howden BP, Ward PB, Charles PG, Korman TM, Fuller A, du Cros P, et al. Treatment outcomes for serious infections caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus with reduced vancomycin susceptibility. Clin Infect Dis. 2004; 38:521–528. PMID: 14765345.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download