Abstract

Nocardia pseudobrasiliensis is predominantly associated with invasive infections in immunocompromised patients. We report a case of disseminated mycetoma caused by N. pseudobrasiliensis in a 57-yr-old woman with microscopic polyangiitis, who was treated for 3 months with corticosteroids. The same organism was isolated from mycetoma cultures on the patient's scalp, right arm, and right leg. The phenotypic characteristics of the isolate were consistent with both Nocardia brasiliensis and N. pseudobrasiliensis, i.e., catalase and urease positivity, hydrolysis of esculin, gelatin, casein, hypoxanthine, and tyrosine, but no hydrolysis of xanthine. The isolate was identified as N. pseudobrasiliensis based on 16S rRNA and hsp65 gene sequencing. The patient was treated for 5 days with intravenous ampicillin/sulbactam, at which time both the mycetomas and fever had subsided and discharged on amoxicillin/clavulanate. This case highlights a very rare presentation of mainly cutaneous mycetoma caused by N. pseudobrasiliensis. This is the first reported case of N. pseudobrasiliensis infection in Korea.

Nocardia are aerobic actinomycetes that can cause pulmonary or central nervous system (CNS) infections in immunocompromised hosts and primary cutaneous infections in immunocompetent hosts [1]. The route of infection is usually either trauma-related introduction or inhalation of the organism [2]. Most reported cases of Nocardia infections in Korea have likewise occurred in immunocompromised hosts, with Nocardia farcinica as the most prevalent infecting species [3-5]. In 1996, the bacterium was distinguished from Nocardia brasiliensis based on the results of distinct biochemical tests, mycolic acid patterns, antimicrobial susceptibilities, and DNA-DNA hybridization. Additionally, although Nocardia pseudobrasiliensis is predominantly associated with invasive infections in immunocompromised hosts, N. brasiliensis is most commonly associated with primary cutaneous infections in immunocompetent individuals [6, 7]. In this study, we report a case of multiple mycetomas caused by N. pseudobrasiliensis. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of N. pseudobrasiliensis infection in Korea.

A 57-yr-old woman was admitted to the emergency department of our hospital on July 3, 2012. She had tender erythematous nodules scattered on her scalp, right arm, right leg, and abdomen that had developed 2 weeks earlier (Fig. 1A and B). Despite a 3-day course of cefaclor that was prescribed by the primary hospital, the lesions had not subsided. In addition, for the past 3 months, she had been on corticosteroid therapy for the treatment of pulmonary microscopic polyangiitis. One year earlier, she had been diagnosed with end-stage renal disease, necessitating hemodialysis 3 times a week.

Her blood pressure in the emergency department was 152/102 mmHg; she had a pulse rate of 120/min, a respiration rate of 20/min, and a body temperature of 38.4℃. Active lung lesions were not observed on the chest radiograph. The results of a complete blood cell count were as follows: white blood cell count, 17.4×109/L; hemoglobin, 10.6 g/dL; and platelet count, 306×109/L. Her serum C-reactive protein level was 50.29 nmol/L.

Biopsies of the nodules on her scalp, right arm, and right leg revealed inflammation and pus formation, which were evident on hematoxylin and eosin stained histological preparations (Fig. 1C); many neutrophils but no organisms were detected by Gram staining. The 3 sets of blood cultures taken at admission were negative. Bacterial and fungal cultures of the biopsied tissues from mycetomas on the patient's scalp, right arm, and right leg yielded tiny white colonies on blood agar and Sabouraud dextrose agar after a 2-day incubation. Over time, the colonies grew larger, taking on an irregular wrinkled appearance with an orange color and a chalky white powder covering (Fig. 2C). The responsible organism consisted of thin, filamentous branching, Gram-positive, and modified Kinyoun-positive rods (Fig. 2A and B).

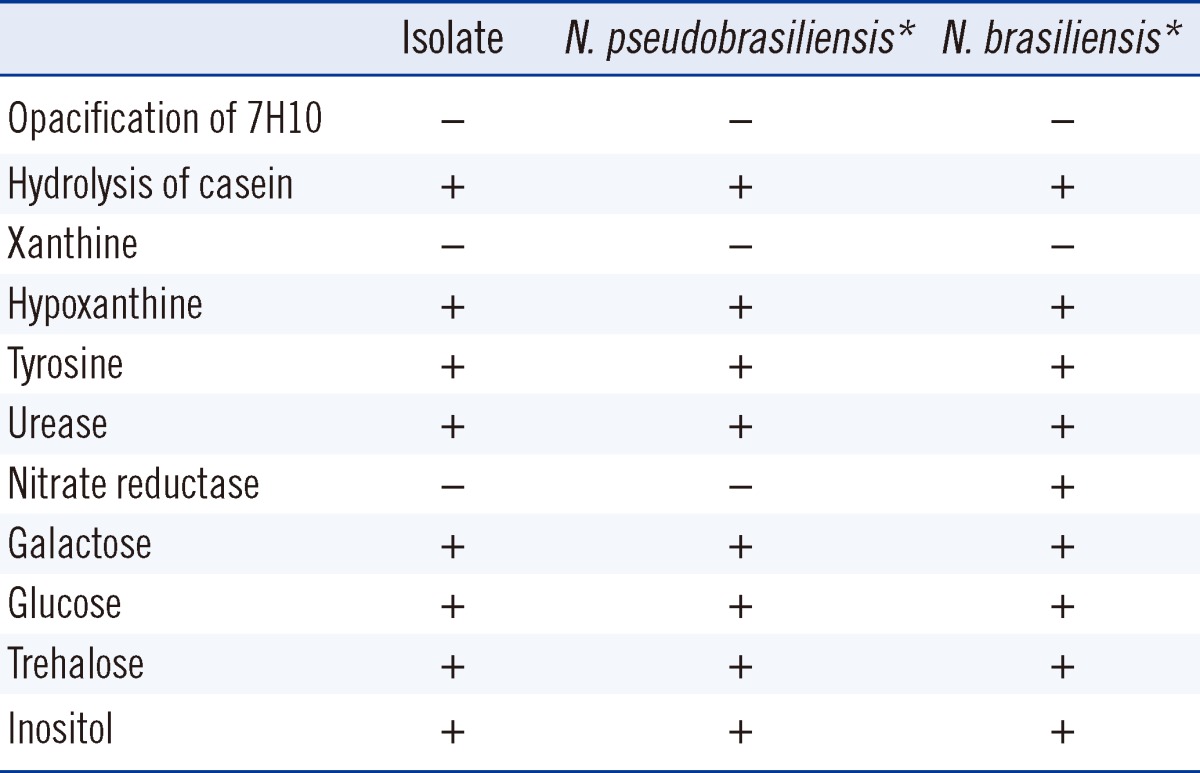

Tests of the organism for catalase and urease were positive, as were those for casein, hypoxanthine, and tyrosine hydrolysis, whereas opacification of 7H10 agar and hydrolysis of xanthine were not observed (Table 1, Fig. 2D). A culture prepared in tap water agar revealed growth of the isolate with aerial hyphae. In the other biochemical tests performed using API Coryne and API 20C AUX (BioMèrieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France), the organism was negative for nitrate reductase, positive for esculin and gelatin hydrolysis, and positive for the assimilation of glucose, glycerol, galactose, N-acetyl-D-glucosamine, inositol, and trehalose. Growth of the isolate at 45℃ was poor after a 3-day incubation. Most of these phenotypic results were consistent with both N. brasiliensis and N. pseudobrasiliensis, with the latter more likely based on the negative nitrate reductase test.

In direct PCR sequencing of 1,350 bp of 16S rRNA obtained from the isolate, 99.5% (1,305/1,312) homology with the published sequence of N. pseudobrasiliensis ATCC 51512T and 98.3% homology with that of N. otitidiscaviarum DSM 43242T were determined. In addition, the hsp65 sequence of the organism exhibited 99.5% (408/410) homology with the corresponding sequence of N. pseudobrasiliensis strain DSM 44290T and 97.3% homology with that of N. transvalensis strain DSM 46068T [8]. In line with the CLSI guidelines [9], the organism was identified as Nocardia, most closely related to N. pseudobrasiliensis. The organism was finally identified as N. pseudobrasiliensis based on its phenotypic characteristics and 16S rRNA and hsp65 gene sequencing.

After the patient was treated with a 5-day course of intravenous ampicillin/sulbactam as an empirical therapy for end-stage renal disease, the multiple mycetomas and fever subsided. She was discharged with a 1-month prescription for amoxicillin/clavulanate. The patient was successfully treated with 6 months of antibiotics therapy.

The organism was tested for antimicrobial susceptibility by the broth microdilution method, performed using the Sensititre Rapid Growing Mycobacteria Plate Format (TREK Diagnostic Systems Limited, East Grinstead, UK). The inoculum was prepared in BACTEC Plus Aerobic/F medium (Becton Dickinson Diagnostic Systems, Sparks, MD, USA) instead of cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth, because the organism grew poorly in the latter. The test results revealed a minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of 8/152 for trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (TMP/SMX). The MICs of other antibiotics were as follows: ciprofloxacin, ≤0.12; moxifloxacin ≤0.25; cefoxitin, >128; amikacin, 4; doxycycline, 16; tigecycline, 4; clarithromycin, 0.25; linezolid, ≤1; imipenem, 64; cefepime, 16; amoxicillin/clavulanate, 32/16; ceftriaxone, 8; minocycline, >8; and tobramycin, ≤1. These data suggested resistance against TMP/SMX, cefoxitin, doxycycline, imipenem, amoxicillin/clavulanate, and minocycline [10].

In this case, N. pseudobrasiliensis was identified by biochemical methods and sequencing of the 16S rRNA and hsp65 genes. N. brasiliensis and N. pseudobrasiliensis are biochemically indistinguishable by traditional amino acid hydrolysis tests; both are positive for the hydrolysis of casein, hypoxanthine, and tyrosine but negative for the hydrolysis of xanthine. Although adenine hydrolysis and nitrate reductase are useful for differentiating the 2 species, given that N. pseudobrasiliensis is positive for adenine hydrolysis and negative for nitrate reductase whereas the converse is true for N. brasiliensis, these tests are not commonly used in the identification of Nocardia species [6, 11]. Therefore, if the results of amino acid hydrolysis testing indicate N. brasiliensis, then 16S rRNA gene sequencing is desirable as a next step to differentiate between this bacterium and N. pseudobrasiliensis.

In this case, the patient manifested only cutaneous lesions, i.e., multiple mycetomas. However, most patients with N. pseudobrasiliensis infections are immunocompromised, and the primary clinical signs and symptoms are typically pulmonary or CNS involvement, which indicates disseminated infection. For example, disseminated N. pseudobrasiliensis infection involving the skin, lungs, and joints was reported in an AIDS patient in Brazil. Pulmonary nocardiosis caused by N. pseudobrasiliensis infection was also detected in a patient in Japan who underwent chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and surgery for esophageal and stomach cancer [12, 13]. CNS infection by a multidrug-resistant strain of N. pseudobrasiliensis was reported in an immunocompetent child. An opportunistic N. pseudobrasiliensis infection occurred in a patient with multiple myeloma, who received an allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant [14, 15]. In contrast to these cases, N. pseudobrasiliensis infection, in which there is only skin involvement, such as in case of mycetoma, is rare. Interestingly, the mycetomas in our patient involved unusual sites, such as the scalp and abdomen. Our patient was on long-term corticosteroid therapy and had no definite history of skin trauma. Although blood cultures were futile, the simultaneous development of mycetoma at multiple sites including unusual sites together with an unexplained fever suggested a disseminated infection.

The antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of the isolated organism was consistent with N. pseudobrasiliensis, which has been consistently reported to be susceptible to ciprofloxacin, clarithromycin, and linezolid and resistant to minocycline and amoxicillin/clavulanate [16, 17]. Unexpectedly, however, the isolate was resistant to TMP/SMX, a property of N. pseudobrasiliensis that has not been definitively described thus far. N. pseudobrasiliensis is resistant to TMP/SMX in the disk diffusion tests, but susceptible in the broth microdilution tests [7]. However, our isolate was resistant to TMP/SMX in both of these tests, suggesting the intrinsic resistance of the isolate to these antibiotics, in contrast to previous reports. Furthermore, our patient was successfully treated with ampicillin/sulbactam and amoxicillin/clavulanate despite the resistance of the isolate to the latter combination in the antimicrobial susceptibility test. Thus, the clinical implications of antimicrobial susceptibility testing for Nocardia species require further clarification.

In conclusion, to our knowledge, we report the first case of N. pseudobrasiliensis infection in Korea, which presented mainly as cutaneous mycetoma. In clinical laboratory testing, 16S rRNA gene sequencing may be the best option to identify N. pseudobrasiliensis, as key biochemical tests differentiating Nocardia species are rarely available in the hospital setting.

References

1. Wilson JW. Nocardiosis: updates and clinical overview. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012; 87:403–407. PMID: 22469352.

2. Ambrosioni J, Lew D, Garbino J. Nocardiosis: updated clinical review and experience at a tertiary center. Infection. 2010; 38:89–97. PMID: 20306281.

3. Heo ST, Ko KS, Kwon KT, Ryu SY, Bae IG, Oh WS, et al. The first case of catheter-related bloodstream infection caused by Nocardia farcinica. J Korean Med Sci. 2010; 25:1665–1668. PMID: 21060759.

4. Moon JH, Cho WS, Kang HS, Kim JE. Nocardia brain abscess in a liver transplant recipient. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2011; 50:396–398. PMID: 22200027.

5. Park BS, Park YJ, Kim YJ, Kang SW, Kim YH, Shin JH, et al. A case of disseminated Nocardia farcinica diagnosed through DNA sequencing in a kidney transplantation patient. Clin Nephrol. 2008; 70:542–545. PMID: 19049715.

6. Ruimy R, Riegel P, Carlotti A, Boiron P, Bernardin G, Monteil H, et al. Nocardia pseudobrasiliensis sp. nov., a new species of Nocardia which groups bacterial strains previously identified as Nocardia brasiliensis and associated with invasive diseases. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1996; 46:259–264. PMID: 8573505.

7. Wallace RJ Jr, Brown BA, Blacklock Z, Ulrich R, Jost K, Brown JM, et al. New Nocardia taxon among isolates of Nocardia brasiliensis associated with invasive disease. J Clin Microbiol. 1995; 33:1528–1533. PMID: 7650180.

8. Yin X, Liang S, Sun X, Luo S, Wang Z, Li R. Ocular nocardiosis: HSP65 gene sequencing for species identification of Nocardia spp. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007; 144:570–573. PMID: 17698022.

9. Clinical and Laboratory Standard Institute. Interpretive criteria for identification of bacteria and fungi by DNA target sequencing; Approved guideline. MM18-A. 2008. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute.

10. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Susceptibility testing of mycobacteria, nocardiae, and other actinomycetes; Approved Standard-Second Edition. M24-A2. 2011. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute.

11. Kiska DL, Hicks K, Pettit DJ. Identification of medically relevant Nocardia species with an abbreviated battery of tests. J Clin Microbiol. 2002; 40:1346–1351. PMID: 11923355.

12. Brown BA, Lopes JO, Wilson RW, Costa JM, de Vargas AC, Alves SH, et al. Disseminated Nocardia pseudobrasiliensis infection in a patient with AIDS in Brazil. Clin Infect Dis. 1999; 28:144–145. PMID: 10028089.

13. Kageyama A, Sato H, Nagata M, Yazawa K, Katsu M, Mikami Y, et al. First human case of nocardiosis caused by Nocardia pseudobrasiliensis in Japan. Mycopathologia. 2002; 156:187–192. PMID: 12749583.

14. Lebeaux D, Lanternier F, Degand N, Catherinot E, Podglajen I, Rubio MT, et al. Nocardia pseudobrasiliensis as an emerging cause of opportunistic infection after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. J Clin Microbiol. 2010; 48:656–659. PMID: 19940053.

15. Mongkolrattanothai K, Ramakrishnan S, Zagardo M, Gray B. Ventriculitis and choroid plexitis caused by multidrug-resistant Nocardia pseudobrasiliensis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008; 27:666–668. PMID: 18520971.

16. Brown-Elliott BA, Brown JM, Conville PS, Wallace RJ Jr. Clinical and laboratory features of the Nocardia spp. based on current molecular taxonomy. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006; 19:259–282. PMID: 16614249.

17. Versalovic J, editor. Manual of clinical microbiology. 2011. 10th ed. Washington, DC: ASM Press.

Fig. 1

Solitary erythematous nodules on the patient's scalp (A) and right arm (B). Histopathological findings of tissue biopsied from the scalp (C) included inflammation and abscess formation (H&E stain, ×100).

Fig. 2

(A) The Gram-stained smear of a cultured colony reveals thin and filamentous branching rods (×1,000). (B) Modified-Kinyoun staining reveals weakly positive dotted rods (×1,000). (C) The morphology of colonies of the isolate on SDA after 3-week incubation. (D) Biochemical tests, including the opacification of Middlebrook 7H10 (a) and the hydrolysis of casein (b), xanthine (c), hypoxanthine (d), and tyrosine (e), were interpreted after a 5-day incubation at 35℃. The organism was negative for Middlebrook 7H10 opacification and xanthine hydrolysis but positive for casein, hypoxanthine, and tyrosine hydrolysis (lower row). The un-inoculated media (upper row) are shown for comparison.

Abbreviation: SDA, Sabouraud dextrose agar.

Table 1

Biochemical characteristics of the isolate in this study compared with N. pseudobrasiliensis and N. brasiliensis in previous reports

*Data from [16].

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download