Abstract

We herein report a case in which the recently characterized species Mycobacterium monacense was isolated from the sputum of an Iranian patient. This case represents the first isolation of M. monacense from Iran. The isolate was identified by conventional and molecular techniques. Our findings show that M. monacense infection is not restricted to developed countries.

Mycobacterium monacense is a rapidly growing Mycobacterium (RGM) that was first isolated from independent clinical specimens in 2006 [1]. Subsequently, 3 additional studies from the United States, Germany, and India have reported the isolation of M. monacense from human clinical samples [2-4]. Here, we report the first case of human isolate of M. monacense from a chronic respiratory infection in Iran identified by a combination of phenotypic and molecular tests.

A 57-yr-old female was admitted to a hospital in the suburb of Isfahan, Iran, for respiratory impairment with chronic productive cough and chest pain. She had no history of mycobacterial infection. A purified protein derivative (PPD) skin test was positive to 5 TU (>12 mm). A chest X radiograph revealed clusters of small (>5 mm) nodules. Based on radiological findings, a positive tuberculin test, the presence of acid-fast bacilli (AFB) in a direct smear of sputum, and isolation of the same strain on 3 repeated examinations, the patient was prescribed anti-tuberculosis drugs and was entered into the tuberculosis register. However, an examination of the cultured infecting organism revealed a yellow-pigmented, rapidly growing scotochromogenic Mycobacterium. Therefore, following the primary identification of the causative agent, the patient's treatment was changed to combination therapy with amikacin and ciprofloxacin. After the initial 45 days of the anti-tuberculosis therapy and the following 45 days of antimicrobial therapy of non-tuberculous pulmonary infection, the patient's general condition improved. Her sputum smears and culture became negative and remained negative at each follow-up examination every 3 months. After discharge from hospital, the patient received a 12-month course of continued treatment at a peripheral center affiliated with the national health care system. During the 24-month follow-up period, the patient did not relapse.

A battery of conventional phenotypic and molecular tests was used to conclusively identify the M11 strain. The phenotypic tests were carried out using standard culture and biochemical methods, as previously described [5]. The susceptibility of the isolate "M11" to major anti-mycobacterial agents was performed using the microdilution method for rapidly growing mycobacteria [6]. For molecular testing a panel of previously defined molecular markers for mycobacteria were used including, PCR amplification of a genus-specific region of the 65-kDa heat shock protein (hsp) gene [7], PCR restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis (PRA) of a 644-bp fragment of the hsp65 gene [8], amplification and direct sequence analysis of the near-full length 16S rDNA and 16S-23S rDNA internal transcribed spacer (ITS) genes, and amplification and direct sequence analysis of partial hsp65 and rpoB genes [9-13]. The GenBank accession numbers of the M11 strain genetic markers in the present study are GU142931, HM229791, HM229792, and HM229793.

Acid-fast bacilli were observed by microscopic evaluation of the sputum sample; the organism was then cultured on Löwenstein-Jensen (LJ) medium. The same isolate was isolated from 3 consecutive sputum samples. The M11 isolate was a rapidly growing (<7 days), scotochromogenic Mycobacterium capable of growth at 25℃, 37℃, and 45℃. Subcultures of the primary isolate had both smooth and rough colony types. Strain M11 was positive for semi-quantitative (100-mm foam) and heat-stable (68℃) catalases, nitrate reduction, Tween® hydrolysis, growth on LJ medium with 5% NaCl, and tellurite reduction. Strain M11 was negative for urease activity, growth on MacConkey agar without crystal violet, arylsulfatase activity (14 days), niacin production, and iron uptake. The M11 isolate was susceptible to amikacin (≤1 µg/mL), cefoxitin (2 µg/mL), ciprofloxacin (≤0.12 µg/mL), clarithromycin (≤0.12 µg/mL), doxicyclin (≤1 µg/mL), ethambutol (≤0.5 µg/mL), imipenem (1 µg/mL), rifampicin (≤0.06 µg/mL), streptomycin (2 µg/mL), and sulfamethoxazol (1 µg/mL).

Genus-specific PCR amplification yielded a characteristic 228-bp fragment of the hsp65 gene, confirming that strain M11 belonged to the genus Mycobacterium. The M11 isolate had a short helix 18 in the 16S rDNA gene, which is a typical molecular signature of rapidly growing mycobacteria.

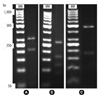

In the PRA method targeting the 644-bp fragment, the M11 isolate's restriction profile consisted of 456/180-bp, 270/161/117-bp and 320/207-bp fragments from digestion with AvaII, HphI, and HpaII, respectively. This restriction profile is distinct from those of other previously characterized atypical mycobacteria (Fig. 1).

The near-full length (1,438-bp) 16S rDNA gene sequence of the M11 isolate shared 99.93% identity with that of M. monacense DSM44395T, 99.23% identity with that of M. doricum DSM44339T, and 97.89% identity with that of M. vaccae ATCC 15483T. Accordingly, there were 1, 13, and 29 nucleotide differences, respectively. The first and second hypervariable signature sequences of the M11 isolate (positions 128-270 and 408-503; Escherichia coli numbering) shared 100% identity with those of the M. monacense type strain (Table 1).

In a phylogeny generated using the 16S rDNA gene, the M11 isolate was classified as an RGM species, and was closely related to M. monacense (Fig. 2).

The M11 isolate's hsp65 gene sequence shared 99.09% identity with that of M. monacense. Its ITS gene sequence also shared 97.83% identity with that of M. monacense clone F1-05352. The M11 isolate's 745-bp fragment of the rpoB gene had a unique sequence compared to those of other atypical mycobacteria; however a comparison was not made between the M11 isolate and of the M. monacense type strain because its relevant data was not available in the molecular databases.

In countries with limited resources, such as Iran, the identification of non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) species by only routine conventional tests (e.g., direct microscopy and culture analysis) may result in erroneous or incomplete diagnosis. As a result, infections caused by these organisms may be underdiagnosed or misdiagnosed and, accordingly, mistreated [14, 15]. Fortunately, the use of molecular tests in conjunction with conventional phenotypic tests has shown significant promise in accurately identifying clinically relevant NTM [14-16].

In 2006, M. monacense was first characterized as a new species following its isolation from the bronchial lavage of an elderly patient and from a biopsy of an injury-acquired fistula in a healthy child [1]. Since then, 3 additional cases of M. monacense isolation from clinical samples have been published. Taieb et al. [2] reported the isolation of M. monacense from a hand infection of an American diabetic patient. Hogardt et al. [3] reported a pulmonary tuberculosis-like infection in a Chinese patient who had traveled to Europe, suggesting that it might have originated in China. In the most recent report, Therese et al. reported the first case of M. monacense isolation from the sputum of a female patient in India [4].

In all but one of the reported cases, the clinical significance of isolation of M. monacense remains uncertain. Specifically, Hogardt et al. [3] presented the only case of a pulmonary disease associated with M. monacense which was isolated from a pulmonary tumor of a Chinese patient. The current report described a pulmonary disease attributable to infection with M. monacense ; this could support a clinically relevant role for this organism. In addition to its phenotypic features, the molecular tests used in the current study suggested that the Iranian isolate belonged to the M. monacense species. Specifically, it shared the highest identity with the 16S rDNA and hsp65 gene sequences of M. monacense, as opposed to those of other published mycobacteria.

The M11 isolate was considered the causative agent of disease in this case, because the acid-fast bacilli were microscopically observed in more than one diseased specimen and were subsequently recovered from a pure culture. Furthermore, no such organism had been isolated in our laboratory previously or during the same time. Our case also met the minimum evaluation criteria for patients suspected of non-tuberculous mycobacterial lung disease set by the American Thoracic Society [17]. These criteria include pulmonary symptoms, a positive chest radiograph, and 3 sputum specimens positive for AFB.

This report follows a case in the United States, which confirms Hogardt's suggestion that M. monacense infection is not restricted to Europe [12]. Consistent with previous reports on most non-tuberculous mycobacteria, our findings indicate that molecular markers are important for the identification of rare clinical isolates of atypical mycobacteria. Consequently, we recommend that developing countries centralize the laboratory diagnosis of rare NTM to a regional referral laboratory in order to avoid misidentification.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

PCR restriction fragment length polymorphism patterns obtained from digestion of the amplified hsp65 gene of the isolate "M11" with HphI (A), HpaII (B) and AvaII (C), respectively. MW: the 50 bp molecular weight marker.

Acknowledgement

The authors are grateful to the Office of Vice-chancellor for Research at Isfahan University of Medical Sciences for financial support.

References

1. Reischl U, Melzl H, Kroppenstedt RM, Miethke T, Naumann L, Mariottini A, et al. Mycobacterium monacense sp. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2006. 56:2575–2578.

2. Taieb A, Ikeguchi R, Yu VL, Rihs JD, Sharma M, Wolfe J, et al. Mycobacterium monacense : a mycobacterial pathogen that causes infection of the hand. J Hand Surg Am. 2008. 33:94–96.

3. Hogardt M, Schreff AM, Naumann L, Reischl U, Sing A. Mycobacterium monacense in a patient with a pulmonary tumor. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2008. 61:77–78.

4. Therese KL, Gayathri R, Thiruppathi K, Madhavan HN. First report on isolation of Mycobacterium monacense from sputum specimen in India. Lung India. 2011. 28:124–126.

5. Kent PT, Kubica GP. Public health mycobacteriology: a guide for the level III laboratory. 1985. Atlanta, Ga: Centers for Disease Control, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

6. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Document No. M24-A. Susceptibility testing of mycobacteria, nocardiae, and other aerobic actinomycetes; Approved Standard. 2003. Wayne, PA: NCCLS.

7. Khan IU, Yadav JS. Development of a single-tube, cell lysis-based, genus-specific PCR method for rapid identification of mycobacteria: optimization of cell lysis, PCR primers and conditions, and restriction pattern analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 2004. 42:453–457.

8. Kim H, Kim SH, Shim TS, Kim MN, Bai GH, Park YG, et al. PCR restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis (PRA)-algorithm targeting 644 bp Heat Shock Protein 65 (hsp65) gene for differentiation of Mycobacterium spp. J Microbiol Methods. 2005. 62:199–209.

9. Shojaei H, Magee JG, Freeman R, Yates M, Horadagoda NU, Goodfellow M. Mycobacterium elephantis sp. nov., a rapidly growing non-chromogenic Mycobacterium isolated from an elephant. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2000. 50(Pt 5):1817–1820.

10. Roth A, Fischer M, Hamid ME, Michalke S, Ludwig W, Mauch H. Differentiation of phylogenetically related slowly growing mycobacteria based on 16S-23S rRNA gene internal transcribed spacer sequences. J Clin Microbiol. 1998. 36:139–147.

11. Kim H, Kim SH, Shim TS, Kim MN, Bai GH, Park YG, et al. Differentiation of Mycobacterium species by analysis of the heat-shock protein 65 gene (hsp65). Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2005. 55:1649–1656.

12. Adekambi T, Colson P, Drancourt M. rpoB-based identification of nonpigmented and late-pigmenting rapidly growing mycobacteria. J Clin Microbiol. 2003. 41:5699–5708.

13. Jeon YS, Chung H, Park S, Hur I, Lee JH, Chun J. jPHYDIT: a JAVA-based integrated environment for molecular phylogeny of ribosomal RNA sequences. Bioinformatics. 2005. 21:3171–3173.

14. Shojaei H, Heidarieh P, Hashemi A, Feizabadi MM, Daei Naser A. Species identification of neglected nontuberculous mycobacteria in a developing country. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2011. 64:265–271.

15. Tortoli E, Rogasi PG, Fantoni E, Beltrami C, De Francisci A, Mariottini A. Infection due to a novel Mycobacterium, mimicking multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010. 16:1130–1134.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download