Abstract

Congenital chloride diarrhea (CLD) is an autosomal recessive disorder with the hallmark of persistent watery Cl--rich diarrhea from birth. Mutations in the solute carrier family 26, member 3 (SLC26A3) gene, which encodes a coupled Cl-/HCO3- exchanger in the ileum and colon, are known to cause CLD. Although there are a few reports of CLD patients in Korea, none of these had been confirmed by genetic analysis. Here, we describe the case of a Korean infant with clinical features of CLD. Using direct sequencing analysis, we identified 2 sequence variants: a missense variant of unknown significance (c.525G>C; p.Arg175 Ser) and a splicing mutation (c.2063-1G>T) in the SLC26A3 gene; these had been inherited from the father and mother, respectively. Whilst CLD is rare, its main symptom, diarrhea, is very common in infants. Hence, the diagnosis of CLD can prove difficult. Mutational analysis of the SLC26A3 gene should be considered as a viable method to confirm a diagnosis of CLD in Korean infants with persistent diarrhea.

Congenital chloride diarrhea (CLD; OMIM 214700) is a rare intestinal disorder inherited in an autosomal recessive manner. It is characterized by defective intestinal electrolyte absorption, resulting in voluminous osmotic diarrhea with high chloride content. The diarrhea begins in utero and causes polyhydramniosis and premature delivery [1]. Mutations in the SLC26A3 (solute carrier family 26, member 3; MIM 126650) gene on chromosome 7q31, which functions as a coupled Cl-/HCO3- exchanger, are responsible for the disease [2]. The transport function of the SLC26A3 protein is thought to play a role in Cl- absorption and HCO3- secretion in the colon. Although CLD has been reported in various ethnicities, there have been few reports in Korea, and no case has been confirmed by genetic analysis of the SLC26A3 gene [3, 4]. Here, we report the case of a male infant with CLD in whom 2 mutations of the SLC26A3 gene were identified.

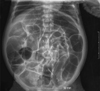

A male infant was delivered preterm at 34+5 weeks of gestation with a birth weight of 2,780 g, via breech cesarean section. Prenatal ultrasonography revealed the presence of dilated bowel loops and polyhydramnios. Soon after delivery, the infant was transferred to the neonatal intensive care unit because he passed greenish watery stool and had abdominal distension. Intestinal obstruction was ruled out on the basis of a physical examination and simple abdominal radiography (Fig. 1). Watery diarrhea, with a frequency of 9-10 times daily, was present; fecal electrolyte concentrations were as follows: Cl-, 135 mEq/L; Na+, 138 mEq/L; and K+, 6.5 mEq/L. Congenital chloride diarrhea was suspected, and as mutations in the SLC26A3 gene are known to be a cause of this disease, we analyzed the gene.

After obtaining informed consent, we collected peripheral blood specimens from the patient and his family. Genomic DNA was extracted from blood leukocytes by using the Wizard Genomic DNA Purification kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. All coding exons and flanking intronic sequences of SLC26A3 (Reference cDNA sequence: NM_000111.2) were amplified and sequenced using primers designed by the authors.

Direct sequencing of the SLC26A3 gene revealed the compound heterozygous mutations. One was a missense variant in exon 5, resulting in a G-to-C substitution at nucleotide position 525 and leading to the substitution of the 175th amino acid residue arginine with serine (c.525G>C; p.Arg175Ser). The other was a splice site mutation occurring in the consensus acceptor site of intron 18 (c.2063-1G>T), which has been listed in the Korean Mutation Database (http://kmd.cdc.go.kr/kmd/search?type=geneid&query=NM_000111.2). A family study revealed that his father and mother were heterozygous carriers of the missense variant and splice site mutation, respectively (Fig. 2), and the novel c.525G>C (p.Arg175Ser) variant was not observed in 376 control chromosomes examined.

CLD, one of the most common hereditary forms of diarrhea, was first described in 1945 by Gamble and Darrow, and more than 250 cases have since been reported worldwide [5, 6]. The countries with a higher than global incidence are Finland (1:10,000), Poland (1:200,000), and Persian Gulf countries including Saudi Arabia and Kuwait (1:5,500); with the exception of these countries, the disease is rare [7]. The incidence of CLD is not known in Korea, and only few cases have been reported to date [4].

SLC26A3, the gene responsible for CLD, resides on chromosome 7q31. SLC26A3 encodes an 85-kDa transmembrane glycoprotein consisting of 764 amino acids [2]. The SLC26A3 protein is an apical epithelial exchanger that transports Cl- across the apical cell membrane in exchange for HCO3- in the surface epithelium of the ileum and colon [2]. The basic mechanism of CLD is loss of SLC26A3-mediated transport in the ileum and colon. If active Cl- reabsorption is defective, massive amounts of Cl- are lost in the stools. The defect in HCO3- secretion leads to metabolic alkalosis with secondary disruption of Na+/H+ transport, resulting in the intestinal loss of both NaCl and fluid. The high intestinal electrolyte content leads to profuse osmotic diarrhea [8].

Because of the intrauterine onset of diarrhea, CLD manifests itself on ultrasonography as a dilatation in the intestinal loops as well as polyhydramnios. Patients are born slightly prematurely because of intrauterine diarrhea [9]. After birth, the persistent intestinal loss of acidic fluid and chloride leads to hypochloremia, metabolic alkalosis, hyponatremia, hypokalemia, and dehydration. Additional clinical findings are malnutrition, hyperbilirubinemia, and failure to thrive [1]. Untreated CLD is mainly fatal during the first weeks or months of life, and infants who survive with undiagnosed disease are likely compensating for their diarrheal losses with a salty diet [10]. Early diagnosis and sufficient salt substitution therapy with NaCl and KCl allow for normal development and favorable prognosis [11]. Untreated, or poorly treated, disease results in several complications, such as constant dehydration and hypoelectrolytemia, retarded growth and development, activation of the renin-aldosterone system, renal involvement, chronic kidney disease, hyperuricemia, and male subfertility and spermatoceles resulting from defectwive Cl-/HCO3- exchange in the male reproductive tract [11].

The diagnosis of CLD is generally based on its typical clinical features and high concentration of fecal Cl- (exceeding 90 mmol/L) after correction of fluid and salt depletion. However, excessive salt and volume depletion reduces the amount of diarrhea and may result in a low fecal Cl- reading of even 40 mmol/L [12]. Watery diarrhea sometimes goes unnoticed during the neonatal period because the stool in diapers resembles urine [10]. This confusing situation may lead to misdiagnosis or significantly delayed diagnosis. Therefore, many patients are likely to die before correct diagnosis and treatment. Thus, genetic analysis is essential to confirm diagnosis in patients with suspected CLD [13].

Our patient showed several symptoms clinically compatible with CLD, such as persistent watery Cl--rich diarrhea, abdominal distention, and intrauterine signs (prematurity and polyhydramnios). We found 2 heterozygous variants in the SLC26A3 gene. The c.525G>C (p.Arg175Ser) is a novel missense variant, which has been predicted to be damaging in PolyPhen (polymorphism phenotyping, http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph/), and the other mutation c.2063-1G>T is a splicing mutation in the acceptor site of intron 18. The c.2063-1G>T mutation has not been reported in the literature but is listed in the Korean Mutation Database (http://kmd.cdc.go.kr/kmd/search?type=geneid&query=NM_000111.2). Further analysis of the parents revealed that each variant was inherited from his parents; this was compatible with the autosomal recessive inheritance pattern of the disease. Intravenous NaCl and KCl supplementation was started, and this was later changed to oral supplementation. His diarrhea improved over time and so did his clinical condition. Following a checkup at 3 months of age, it was revealed that all developmental milestones were normal for his age. He was started on a regular formula at 6 months. The sodium, potassium, and chloride levels were normal with a supplementation of NaCl 4 mmol/kg/day, divided over 3 doses a day. He showed mild abdominal distension and passed loose stools 2 or 3 times per day, but his general condition was good.

In summary, our patient is the first Korean patient with CLD in whom mutational analysis of the SLC26A3 gene was performed. CLD should be considered in infants presenting with intractable, watery Cl--rich diarrhea. In practical clinical work, the diagnosis of CLD is difficult, since the disorder itself is rare in Korea and its main symptom, diarrhea, is common. Mutational analysis of the SLC26A3 gene should be considered to establish an accurate diagnosis, particularly if the clinical diagnosis remains uncertain.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 2

Sequence analysis of the SLC26A3 gene. The patient had a compound heterozygous missense variant in exon 5 (c.525G>C; p.Arg 175Ser) and a splicing mutation in intron 18 (c.2063-1G>T); the father and mother were heterozygous carriers of each of the variants, respectively. Arrows indicate the variant sequences.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by a Samsung Biomedical Research Institute (SBRI) grant (C-B0-206-2).

References

2. Höglund P, Haila S, Socha J, Tomaszewski L, Saarialho-Kere U, Karjalainen-Lindsberg ML, et al. Mutations of the down-regulated in adenoma (DRA) gene cause congenital chloride diarrhoea. Nat Genet. 1996. 14:316–319.

3. Lee YD, Lee HJ, Moon HR. Congenital chloridorrhea in Korean infants. J Korean Med Sci. 1988. 3:123–129.

4. Yoon SK, Kim EY, Moon KR, Park SK. A case of congenital chloride diarrhea in premature infant. J Korean Pediatr Soc. 2003. 46:308–311.

6. Wedenoja S, Pekansaari E, Höglund P, Mäkelä S, Holmberg C, Kere J. Update on SLC26A3 mutations in congenital chloride diarrhea. Hum Mutat. 2011. 32:715–722.

7. Höglund P, Auranen M, Socha J, Popinska K, Nazer H, Rajaram U, et al. Genetic background of congenital chloride diarrhea in high-incidence populations: Finland, Poland, and Saudi Arabia and Kuwait. Am J Hum Genet. 1998. 63:760–768.

8. Moseley RH, Höglund P, Wu GD, Silberg DG, Haila S, de la Chapelle A, et al. Downregulated in adenoma gene encodes a chloride transporter defective in congenital chloride diarrhea. Am J Physiol. 1999. 276:G185–G192.

9. Kirkinen P, Jouppila P. Prenatal ultrasonic findings in congenital chloride diarrhoea. Prenat Diagn. 1984. 4:457–461.

10. Ozen H, Tanriöğer N. Congenital chloride diarrhea in a Turkish boy. Turk J Pediatr. 1996. 38:235–238.

11. Wedenoja S, Höglund P, Holmberg C. Review article: the clinical management of congenital chloride diarrhoea. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010. 31:477–485.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download