This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to determine whether the menstrual characteristics are different in Korean women with or without ovarian endometrioma.

Methods

We selected 95 premenopausal women aged below 39 years who underwent laparoscopic surgery for ovarian endometrioma (n=46) or other benign ovarian tumors (n=49) between April 2016 and February 2017. We excluded those with uterine diseases that could potentially affect the menstrual characteristics and those on anticoagulants or hormonal medication. At admission, menstrual characteristics such as cycle length, cycle regularity, and menstrual duration, were collected. In addition, amount of menstrual bleeding and severity of dysmenorrhea were recorded using a pictorial blood loss assessment chart (PBAC) and visual analogue scale, respectively.

Results

Age and parity were similar in both women with ovarian endometrioma and women with other benign ovarian tumors. Body mass index (BMI) was significantly lower (median, 20.9 vs. 22.1 kg/m2; P=0.031) in women with ovarian endometrioma. The amount of menstrual bleeding (median PBAC score, 183 vs. 165), menstrual duration (median, 6 vs. 6 days), and cycle length in women with regular cycle (median, 29.0 vs. 29.2 days) were not different between the 2 groups. Pain score was significantly higher (median, 4 vs. 3; P=0.005) in women with ovarian endometrioma.

Conclusion

We found that the menstrual characteristics between women with ovarian endometrioma and women with other benign ovarian tumors were similar. We also observed that low BMI may be one of the risk factor for endometriosis.

Keywords: Endometriosis, Menstruation, Menorrhagia, Body mass index

Introduction

Endometriosis is a common gynecologic condition that affects women throughout their reproductive life. Its prevalence rate is 10%–15% in women of reproductive age and may be as high as 30% in infertile women [

1].

Risk factors for endometriosis remain largely unknown; however, it has previously been suggested that young age, low parity, thinness, alcohol usage, cigarette smoking, early age at menarche, and specific menstrual characteristics may be risk-elevating factors for endometriosis [

234567].

Because retrograde flow of menstrual blood cells during menstruation is considered as the dominant theory for the development of endometriosis, a close association between menstrual characteristics and occurrence of endometriosis may be a plausible scenario.

Moreover, specific menstrual characteristics, such as short cycle length and long duration of menstrual flow, have been identified as possible risk factors [

8]. The duration of menstrual bleeding has also been reported as a potential independent risk factor for endometriosis in infertile Iranian women [

5]. However, several studies have indicated that the duration of menstrual bleeding may be similar between women with and without endometriosis [

39]. It has been an ongoing debate whether frequent menstrual cycle is a risk factor for endometriosis; however, a recent meta-analysis revealed that menstrual cycle length of less than or equal to 27 days may increase the risk of endometriosis, whereas a cycle length of greater than or equal to 29 days may decrease the risk [

6].

With respect to the amount of menstrual bleeding, a significantly higher amount was observed in women with endometriosis compared with women without endometriosis, according to a study from Italy (median score 110 vs. 84 when assessed by pictorial blood loss assessment chart [PBAC]) [

9]. In addition, it has also been reported that moderate to severe menstrual bleeding was significantly more prevalent in women with endometriosis compared with those without endometriosis [

35].

To date, only a few studies have evaluated the association between the amount of menstrual bleeding and presence of endometriosis. Moreover, to the best of our knowledge, there is a limited number of studies that used objective methods to assess the amount of menstrual bleeding, such as PBAC score or alkaline hematin measurement. More importantly, data on the amount of menstrual bleeding in Korean women are not available. Thus, in the present study, we evaluated the menstrual characteristics of Korean women with or without endometriosis.

Materials and methods

A total of 95 women younger than 39 years of age, who received laparoscopic surgery for having ovarian endometrioma (n=46) or other benign ovarian tumors (n=49) between April 2016 and February 2017, was included for analysis. The Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University Hospital approved our study (IRB No. 1706-045-857).

We excluded women with uterine diseases that could potentially affect the menstrual characteristics, such as myoma uteri, endometrial polyps, and adenomyosis. We also excluded women who received gynecologic surgeries within the past 6 months for the aforementioned uterine diseases. Moreover, we also excluded women who had taken anticoagulants or hormonal medications (a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist, glucocorticoids, oral contraceptives, progestins, or intrauterine device) within the last 6 months, because it is possible that these drugs may affect the menstrual characteristics.

From the electronic medical records at admission, the data regarding age, height, body weight, and preoperative blood hemoglobin level were collected. At admission, menstrual characteristics, such as cycle length, cycle regularity, and menstrual duration, were collected by using a questionnaire. The amount of menstrual bleeding was recorded using a PBAC, and the severity of dysmenorrhea was recorded using a visual analogue scale.

After laparoscopic surgery, all patients were divided into 2 groups based on the final histology of the pathologic report: the ovarian endometrioma group (n=46) and the other benign ovarian tumors group (without endometriosis) (n=49). The endometriosis score was evaluated in accordance with the revised guidelines proposed by the American Society for Reproductive Medicine [

10].

All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences software (SPSS version 22.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). When the numeric data between the 2 groups were compared, nonparametric Wilcoxon test was used, and the data were expressed as the median and 95% confidence interval. When the proportions between the 2 groups were compared, the χ2 test or the Fisher's exact test was used, when appropriate. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

In the ovarian endometrioma group, 17 women had stage III endometriosis and 29 women had stage IV endometriosis. Among the 49 women with other benign ovarian tumors, the final histology was as follows; 33 mature cystic teratomas, 5 mucinous cystadenomas, 4 follicular cysts, 3 paratubal cysts, 2 serous cystadenomas, 1 hydrosalpinx, and 1 tubo-ovarian abscess.

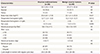

As shown in

Table 1, age and parity were similar in both groups. Women with ovarian endometrioma showed a significantly lower body mass index (BMI) and preoperative hemoglobin level. Pain score was significantly higher in women with ovarian endometrioma. However, cycle regularity, cycle length in women with regular cycle, menstrual duration, and amount of menstrual bleeding were not different between the 2 groups. It is worth noting that we did not analyze the age of menarche because this data was not available in more than half of our participants.

Table 1

Clinical and menstrual characteristics in women with or without ovarian endometrioma

|

Characteristics |

Ovarian endometrioma (n=46) |

Benign ovarian tumors (n=49) |

P

|

|

Age (yr) |

30.5 (29.2–31.8) |

29 (27.5–30.4) |

NS |

|

Married |

14 (30.4) |

16 (32.7) |

NS |

|

Parous |

10 (22) |

11 (22) |

NS |

|

Body mass index (kg/m2) |

20.9 (20.1–21.6) |

22.1 (21.3–23.0) |

0.031 |

|

Preoperative hemoglobin (g/dL) |

12.7 (12.4–13.0) |

13.3 (12.9–13.7) |

0.012 |

|

Preoperative hemoglobin <10 g/dL |

0 |

2 (4) |

NS |

|

Pain score |

4 (3.5–4.4) |

3 (2.5–3.5) |

0.005 |

|

Menstrual amount by PBAC |

183 (155–211) |

165 (133–197) |

NS |

|

PBAC score |

|

|

NS |

|

≥100 |

33 (72) |

35 (71) |

|

≥130 |

29 (63) |

30 (61) |

|

≥160 |

23 (50) |

19 (39) |

|

Menstrual duration (day) |

6 (6–7) |

6 (5–6) |

NS |

|

Menstrual cycle |

|

|

NS |

|

Regular |

40 (87) |

36 (73) |

|

Irregular |

6 (13) |

14 (27) |

|

Cycle length in women with regular cycle (day) |

29.0 (28–30) |

29.2 (28–30) |

NS |

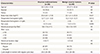

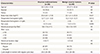

According to the analysis comparing the clinical and menstrual characteristics against the stage of endometriosis, we found that age, BMI, pain score, cycle regularity, cycle length in women with regular cycle, menstrual duration, and amount of menstrual bleeding were all similar between women with stage III endometriosis and those with stage IV endometriosis (

Table 2).

Table 2

Clinical and menstrual characteristics according to the stage of endometriosis

|

Characteristics |

Endometriosis III (n=17) |

Endometriosis IV (n=29) |

P

|

|

Age (yr) |

30.3 (28.2–32.5) |

30.6 (28.9–32.3) |

NS |

|

Married |

5 (29) |

9 (31) |

NS |

|

Parous |

3 (18) |

7 (24) |

NS |

|

Body mass index (kg/m2) |

20.9 (19.5–22.3) |

20.8 (19.9–21.7) |

NS |

|

Preoperative hemoglobin (g/dL) |

12.8 (12.3–13.3) |

12.6 (12.2–13.0) |

NS |

|

Pain score |

3.8 (3.0–4.6) |

4.0 (3.4–4.7) |

NS |

|

Menstrual amount by PBAC |

211 (156–267) |

167 (137–197) |

NS |

|

PBAC score |

|

|

NS |

|

≥100 |

13 (76) |

20 (69) |

|

≥130 |

11 (65) |

18 (62) |

|

≥160 |

9 (53) |

14 (48.3) |

|

Menstrual duration (day) |

6.6 (6.0–7.1) |

6.1 (5.7–6.5) |

NS |

|

Menstrual cycle |

|

|

NS |

|

Regular |

13 (76) |

27 (93.1) |

|

Irregular |

4 (24) |

2 (6.9) |

|

Cycle length in women with regular cycle (day) |

31.0 (29.4–32.6) |

28.6 (27.6–29.5) |

NS |

Discussion

In the present study, the amount of menstrual bleeding was similar between women with and without endometriosis. Moreover, there was no difference in the cycle length, menstrual duration, or menstrual regularity between the 2 groups. This result is inconsistent with previous reports, which showed that amount of menstrual bleeding is greater (110 vs. 84) or menorrhagia is more prevalent in women with endometriosis compared with women without endometriosis [

359].

Short cycle length has previously been proposed as a risk factor for endometriosis [

68]. However, it has also been asserted that long duration of menstrual flow may be a risk factor for endometriosis [

359]. To date, whether the amount of menstrual bleeding should be considered as a risk factor for endometriosis remains to be inconclusive, because there has only been one study assessing the amount of menstrual bleeding using the PBAC score [

9].

In our study, the median PBAC score was rather high in both groups (183 vs. 165), when compared with the PBAC score (110 vs. 84) from a previous report [

9]. The cut-off point of the PBAC score for the diagnosis of menorrhagia has traditionally been 130 [

11]. When using 130 as the cut-off point in our study, the prevalence of menorrhagia was 63% in women with endometriosis and 61% in women without endometriosis. However, in a recent study, 160 was proposed and used as the cut-off point for menorrhagia [

12]. They reported that the median PBAC values in women who reported their blood flow as minimal, normal, or heavy were 45 (range, 2–204), 116 (range, 13–610), and 255 (range, 13–1,740). When using this new cut-off point in our study, the prevalence of menorrhagia was much higher in women with endometriosis (50% vs. 39%); but it did not reach statistical significance.

Because there has not been any study investigating a baseline reference PBAC score for menstrual amount in Korean women, it is unknown whether our study population is representative of women with normal or abnormal menstrual amount.

In the present study, the BMI was significantly lower in women with endometriosis. This is consistent with a previous report that concluded thinness as a risk factor for endometriosis [

13]. The mechanism behind this remains largely unknown. According to a previous report, thin women generally have low level of circulating leptin [

13]. This study also reported that lower concentration of leptin in the peritoneal fluid may be associated with greater severity of endometriosis [

13].

Moreover, young age and low parity have also been suggested as risk factors for endometriosis in previous reports [

2]; however, in our study, age and parity were not different between the endometriosis group and non-endometriosis group. In our study, the preoperative hemoglobin value was lower in women with endometriosis; however, the clinical significance of this might be minimal since the hemoglobin values, despite being lower, were mostly within normal range.

In our study, the pain score was significantly higher in women with endometriosis. This is consistent with the already-existing knowledge of dysmenorrhea causing endometriosis. In general, pain score is not associated with endometriosis stage, and we found a similar pain score between those with stage III endometriosis (median VAS score 3.8) and stage IV endometriosis (median VAS score 4).

The PBAC score system has been proposed by Higham et al. [

14] as a means to evaluate the amount of menstrual bleeding. They showed that this scoring system is directly correlated with the uterine blood loss measured by the alkaline hematin method, and suggested a cut-off value of 100, at which point, both sensitivity and specificity for menorrhagia was shown to be greater than 80%, according to their validation study [

14]. However, in a subsequent study, the cut-off value for menorrhagia has been suggested to be 130; with this score, the sensitivity was 91% and the specificity was 81.9% [

11]. In a recent study, the cut-off value for menorrhagia has been proposed to be 160; with this score, the sensitivity was 78.5% and the specificity was 75.8% [

12]. Taken together, we can conclude that the criteria for the PBAC score system as a means to diagnosis menorrhagia may increase over time. Although the reason behind is unclear, it is likely due to the increasing prevalence of uterine diseases affecting the menstrual amount.

The advantage of our study is that we excluded women with past or current uterine diseases as well as those who had taken anticoagulants or hormonal medications within the past 6 months. It is worth noting that these could affect menstrual characteristics. Another advantage is that we included surgically confirmed control group, in whom endometriosis was absent. In our study, we selected only those who were 39 years or younger, since women older than 40 years would have a high possibility of menorrhagia due to uterine diseases, such as adenomyosis or myoma uteri.

One limitation of this study is that we were unable to investigate whether alcohol usage and cigarette smoking were risk factors for endometriosis. In addition, age of menarche was not incorporated in the final analysis due to lack of available data. Although age of menarche was included in the questionnaire, less than half of the participants responded; it is likely that most women do not remember their age of menarche.

In conclusion, we found similar menstrual characteristics (except pain score) between women with endometriosis and women without endometriosis. Low BMI appears to be one of the risk factor for endometriosis. More research with a large population is necessary to clarify the association between menstrual characteristics and endometriosis risk. In addition, a baseline reference PBAC score for menstrual amounts in Korean women should be investigated.