Abstract

Objective

Investigation of initial 51 cases of single port access (SPA) laparoscopic surgery for large adnexal tumors and evaluation of safety and feasibility of the surgical technique.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of the first 51 patients who received SPA laparoscopic surgery for large adnexal tumors greater than 10 cm, from July 2010 to February 2015.

Results

SPA adnexal surgeries were successfully completed in 51 patients (100%). The mean age, body mass index of the patients were 43.1 years and 22.83 kg/m2, respectively. The median operative time, median blood loss were 73.5 (range, 20 to 185) minutes, 54 (range, 5 to 500) mL, and the median tumor diameter was 13.6 (range, 10 to 30) cm. The procedures included bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (n=18, 36.0%), unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (n=14, 27.45%), and paratubal cystectomy (n=1, 1.96%). There were no cases of malignancy and none were insertion of additional ports or conversion to laparotomy. The cases with intraoperative spillage were 3 (5.88%) and benign cystic tumors. No other intraoperative and postoperative complications were observed during hospital days and 6-weeks follow-up period after discharge.

Adnexal tumor, including ovarian cyst and paratubal cyst, is one of the most common diseases in gynecology and generally occurs during reproductive years. Currently, laparoscopic management is considered as an alternative standard for adnexal tumors. The reported advantages of laparoscopic management include faster recovery, shorter hospital stays, decreased analgesic requirements, fewer perioperative complications, and improved quality of life [1]. Thus, laparoscopic management is regarded as gold standard management of adnexal tumors nowadays [2]. However, the size of adnexal tumors is an important limitation of laparoscopic management. Currently, the precise contraindication concerning the size of adnexal tumor for laparoscopic management is not clearly established. Large adnexal tumor has increased risk of malignancy and capsular rupture. Furthermore, main obstacles of huge adnexal mass operation includes limited surgical field, difficulty in inserting trocars and removing the specimen without rupture or spreading of cystic fluid into abdominal cavity. Recently, to overcome these problems, new surgical laparoscopic technique is suggested for large ovarian cyst [34]. We assessed how safe our surgical approach can be conducted. Our method involves inserting the single port through umbilical incision and reducing the cystic volume through extra- or intra-corporeal aspiration before conducting the remaining surgery. The aim of our study was to evaluate the feasibility and safety of single port access (SPA) extracorporeal laparoscopic surgery among women with large adnexal tumors (≥10 cm in size).

From July 2010 to February 2015, 401 cases of SPA laparoscopic surgery for adnexal tumors were performed at Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Konyang University Hospital, Daejeon, Korea. Among them, 51 cases were eligible for criteria of large adnexa mass (≥10 cm). Our retrospective review for medical records was approved by the institutional review board of our hospital.

We reviewed 51 women with adnexal tumors whose maximum diameter was ≥10 cm. All women underwent a preoperative ultrasound examination and physical examination. When malignancy was suspected, further evaluation such as abdominal and pelvic computed tomography scan or magnetic resonance image, were performed. Furthermore, routine preoperative workup was performed in every patients (patient's abdominal operation history, preoperative laboratory studies including tumor marker such as CA 125, CA 19–9, complete blood count, routine chemistry, electrolyte, prothrombin time/adjusted partial prothrombin time, chest radiography, electrocardiography). Inclusion criteria were as followed: diameter of adnexal mass was ≥10 cm with benign clinical features (e.g., single unilocular cysts, smooth border, no excrescence, no solid portion) and patients who consented to SPA procedures. Patients with an obvious malignancy features in imaging studies, high serum CA 125 levels (>500 U/mL), suspicious severe pelvic adhesions at physical examination, severe obesity (body mass index > 35 kg/m2), and patients who were at high risk for general anesthesia were excluded.

Patient's demographic data including age, body mass index, parity, and surgical data including tumor size, type of surgery, operative time, estimated amount of blood loss, pathologic findings, length of hospital stay, change in hemoglobin level, intraoperative and postoperative complications and the rate of conversion to laparotomy were retrospectively investigated using electronic medical records. Operative time was defined as from incision to wound closure. Hospital day was defined as the time between the operation date and discharge date.

Except for emergency cases (e.g., ovarian cyst torsion, n=6/51), single surgeon (CJK) with extensive training and experience (over 1,500 cases of SPA surgery) and in gynecological oncology performed all procedures. Under general anesthesia, patients were placed in the dorsal lithotomy position. The surgeon stood on the left side of the patient. The first assistant stood on the right side of the patient to handle the scope. The second assistant was positioned between the legs of the patient and modulated the RUMI II system (Cooper Surgical, Trumbull, CT, USA). SPA was performed using a OctoPort (DalimSurgNet, Seoul, Korea), which is composed of 2 parts, a 30-mm wound retractor and a detachable port cap with 3 access ports (two 12-mm ports and one 5-mm port) (Fig. 1).

With the open Hasson technique, a 2-cm vertical incision was made within the umbilicus. After inserting single-port access system through the umbilicus, pneumoperitoneum was maintained with CO2 gas at 8 to 12 mmHg. We used a 0 degree, 5 mm, rigid laparoscope (Panoview, Richard Wolf GMBH, Knittlingen, Germany). Inspection of the ovarian cyst, opposite ovary, peritoneal surface and omentum was performed. When the size of cyst was large enough to reach the umbilical level, the port cap was removed for extracoporeal process to aspirate large adnexal cystic contents. If the cyst size did not reach umbilical level, all procedure was done in intracorporeal method without removing the port cap.

The puncture site was closed by the purse string suture or surgical clips and detachable port cap was reinserted through umbilicus. After then, salpingo-oophorectomy or ovarian cystectomy was performed and tumor specimens were extracted using Endo-Pouch (Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Cincinnati, OH, USA). After cystic tumor removal, the detachable cap was reinserted and final inspection was performed. Peritoneal cavity irrigation with normal saline was done. After removing SPA system from abdominal cavity, peritoneum and fascia of the umbilicus were closed with 2-0 polysorb, and the skin was closed with skin adhesive (Histoacryl, B. Braun, Melsungen, Germany) (Fig. 2).

Fifty-one cases were eligible for criteria of large adnexa mass (≥10 cm). Tables 1 and 2 show respectively the patient demographics and surgical outcomes. The median age, body mass index of the patients were 43.1 years and 22.83 kg/m2, respectively. Intraoperative details and type of procedure are listed in Table 2. The median operative time was 73.5 (range, 20 to 185) minutes.

Intraoperative blood loss was estimated by calculating the difference between the total amount of fluid aspirated and the amount of normal saline used for irrigation. The median estimated blood loss was 54 mL.

The median tumor diameter was 13.6 (range, 10 to 30 cm). The procedures included, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (n=18, 35.3%), unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (n=14, 27.5%), ovarian cystectomy (n=13, 25.4%), unilateral oophorectomy (n=3, 5.9%), unilateral salpingectomy (n=2, 3.9%), and paratubal cystectomy (n=1, 2.0%).

Twelve cases had previous abdominal surgery and among these 12 cases, pelvic adhesion was noted in 6 cases. 3 cases of cesarean section, 2 cases hysterectomy and 1 case of appendectomy, respectively. Emergent surgery was performed in six cases, all emergency cases were diagnosed of adnexal torsion. There were three cases of intraoperative cyst rupture among a total 51 cases (5.9%). In case of ruptured cystic tumors, two cases were mucinous cystadenoma, and one case was a mature cystic teratoma. The abdominal cavity was cleansed entirely with saline solution and examined in detail for any remaining cystic contents in cases of ruptured cystic tumor.

The postoperative courses were variable among patients. The median postoperative hospital day was 5days. Although our hospital recommends patients to be discharged on postoperative day 3, only four patients complied with our policy. Most of the patients extended their hospital day for different reasons. Two patients were discharged on postoperative day 8 and 10 respectively to confirm final pathology type because there was a possibility of malignancy. Except those two cases, other patients were discharged on day 4 to 8 due to personal reasons.

The Table 3 shows histopathological findings of the study population. The pathologic diagnoses were confirmed as mucinous cystadenoma (n=16, 31.4%), mature cystic teratoma (n=9, 17.7%), serous cystadenoma (n=4, 7.8%), serous cystadenofibroma (n=2, 3.9%), endometriotic cyst (n=2, 3.9%), paratubal cyst (n=2, 3.9%), mucinous/serous borderline tumor (n=4/2, 7.8%/3.9%), other benign cyst (n=8, 15.7%), mixed serous and mucinous cystadenoma (n=1, 2.0%), consistent with struma ovarii (n=1, 2.0%). In two cases of borderline tumors, patients were young and wanted to preserve their fertility. Thus, in these cases ovarian cystectomy was performed and other cases were performed with salpingo-oophorectomy. During following period, two cases (3.9%)of borderline ovarian tumors which underwent ovarian cystectomy had an additional operation because adnexal mass newly developed on another site. Those masses were confirmed as hemorrhagic corpus luteal cyst and simple benign epithelial cyst, respectively. In our study, we did not consider these two cases as recurrence and there were no recurred cases noted during a mean follow-up period of 12.5 (range, 1 to 24) months. None of the cases were converted to open laparotomy and no patient experienced major intraoperative or postoperative complications.

Laparoscopic surgery could be considered a gold standard for management of adnexal tumors [2]. The contraindication for laparoscopic management is not clearly established concerning the size of adnexal tumor. Some suggest that proper management for adnexal tumors larger than 8 to 10 cm in size is laparotomy [56]. Recently, several studies have reported the surgical outcomes of SPA laparoscopic surgery for the management of adnexal tumors [78910], however these reports usually excluded large ovarian cyst.

In our report, when the largest diameter of the cyst measured more than 10 cm on preoperative imaging studies, we defined it as large adnexal mass. While this definition was also used in several studies [41112], other articles suggest different criteria. Salem [13] and Sagiv et al. [14] defined the ovarian cyst as “large” and “extremely large” when the edge of the cyst was above the level of the umbilicus. Nevertheless, as each individual have different level of height of umbilicus, we anticipate further studies to establish objective standards to measure and define large ovarian cyst.

The laparoscopic management for large adnexal tumors is mainly excluded because of several challenging techniques, such as difficulty in inserting trocars, spillage of cystic content, and removing surgical specimen. Specifically, the minimal access surgery is more likely to result in capsular rupture than laparotomy because large adnexal tumors often require drainage of intra-cystic contents before removal to achieve adequate working space [11].

Large adnexal tumors may be associated with malignancy and also an increased risk of spillage of malignant cells during surgery. In contrast, significance of this spillage in malignant cases is controversial [15]. Vergote et al. [16] reviewed six international databases, including 1,545 women who underwent laparotomy for early-stage ovarian cancer. This study identified degree of tumor differentiation as the most powerful prognostic indicator of disease free survival (moderate versus well differentiated hazard ratio 3.13 [95% confidence interval, 1.68 to 5.85], poorly versus well differentiated 8.89 [4.96 to 15.9]). Rupture of tumor during surgery was therefore not prognostic (rupture before surgery 2.65 [1.53 to 4.56], rupture during surgery 1.64 [1.07 to 2.51]). Dembo et al. [17] analyzed predictive factors of relapse risk in 519 patients with stage 1 invasive epithelial ovarian cancer. Cyst rupture during surgery did not influence the rate of relapse or prognosis.

Our method may solve these intraoperative complications such as spillage of cystic content into the peritoneal cavity by extracorporeal or intracorporeal cyst aspiration in which the puncture site is closed after aspiration with purse string suture or surgical clip.

Encountering malignant adnexal tumors during laparoscopic management is a major restriction. Although the tumor size has been considered as one of the predictive factors of malignancy [18], in many cases, large adnexal tumors are benign. In a prospective study involving 1,304 women with unilocular cysts operated over a 6-year period, the frequency of benign diagnosis was 93.2% of cases among masses more than 8cm in diameter [19]. Childers et al. [20] investigated 138 patients who underwent operative laparoscopy for removal of suspicious adnexal masses (elevated CA 125 level and/or none of the ultrasound criteria of benignity, including size <10 cm), and benign pathologic condition was found in 86% (119/138) of the patients, and in 88.4% (38/43) of the women with masses of size ranging over 10 cm.

The key point of SPA laparoscopic surgery for large adnexal tumors is that it combines extracorporeal and intracorporeal procedures [21]. Through 2 cm umbilical incision, extracorporeal management such as suction of cystic contents and cystectomy was performed and using laparoscopy, intracorporeal procedures such as inspection and irrigation of pelvic cavity were performed.

Minimal access surgery, specifically, the surgical approach suggested in this study, may reduce the limitations of conventional laparoscopy and laparotomy for treatment of large adnexal tumors. In a prospective randomized study that compared outcomes of laparoscopy and laparotomy conducted for benign ovarian mass less than 10 cm [22], the laparoscopic approach significantly reduced operative morbidity (odds ratio, 0.34; 95% confidence interval, 0.13 to 0.88), postoperative pain and analgesic requirement, hospital stay, and recovery period. In our report, extension of hospitalization (>3 days) was often reported. The extended hospitalization period in Korea may be a distinct characteristic compared to other countries because most patients prefer to be admitted until they fully recover from all the symptoms related to the operation.

In addition, another study also showed superior surgical outcome of single port laparoscopic management compared to former established approach including conventional laparoscopy and laparotomy. Chong et al. [21] compared the outcome of laparoscopy and laparotomy to single port laparoscopic management for large ovarian cyst (>8 cm in greatest diameter on preoperative imaging studies). The surgical outcomes included complications and cystic content spillage rates. Single port laparoscopic management reduced operative time and blood loss in comparison with laparotomy (operative time, 69.3 vs. 87.5 minutes, P=0.02; blood loss, 16.0 [19.4] vs. 42.2 [39.7] mL, P=0.005). Moreover, spillage rate in single port laparoscopic management was significantly lower than conventional laparoscopy (8.0% vs. 69.7%, P<0.001).

One of the major limitations of our investigation is that no comparison between single port laparoscopy and conventional laparoscopy was done since conventional laparoscopy was occasionally performed and there were no laparotomy done. None of the cases underwent laparotomy and only three cases had conventional laparoscopy (3 port access) because severe adhesion was predicted before surgery.

As mentioned above, SPA laparoscopic surgery may reduce spillage rate and facilitate the removal of specimen. Furthermore, present studies provide comparable surgical outcomes and morbidity with conventional laparoscopy. However, there are some basic requirements that are essential for laparoscopic management of large adnexal mass: (1) absence of a gynecologic malignancy and metastasis on image studies; (2) availability of frozen section diagnosis conducted by an expert; and (3) a gynecologic oncologist or surgical team for appropriate cancer surgery.

The strength of this study is relatively large sample size, which approve sufficient power for proper analyses. In addition, by a single surgeon progresses most of the operation, it was able to reduce the variables that may be caused by differences in surgical methods and surgical instruments Our study is limited due to its retrospective single arm design and selection bias may be present. Also, none of the cosmetic outcomes were evaluated. However, our study is significant in terms of covering a relatively large number of patients.

In conclusion, SPA laparoscopic surgery for large adnexal tumors is a safe and feasible alternative compared to conventional laparoscopic surgery. This technique provides superior surgical outcomes that are comparable with those of conventional laparoscopic surgery for women with large adnexal masses, with no increase in perioperative complications and no recurrence after surgery.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 2

(A) Large ovarian cyst (≥10 cm in diameter). (B) Aspiration of cystic contents. (C) Closure by surgical clip of remnant ovarian tissues. (D) Ovarian salpingo-oophorectomy. (E) Intra-pelvic cavity after salpingo-oophorectomy. (F) Postoperative umbilical wound.

Table 1

Patient's demographic data

| Characteristics | Value |

|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 43.1 (10–85) |

| Parity | 1.6 (0–5) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 22.8 (17.2–41.4) |

| No. of previous pelvic surgeries | 12 (23.5) |

Table 2

Surgical outcomes of SPA

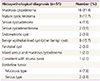

Table 3

Histopathological findings of the study population

References

1. Escobar PF, Starks D, Fader AN, Catenacci M, Falcone T. Laparoendoscopic single-site and natural orifice surgery in gynecology. Fertil Steril. 2010; 94:2497–2502.

2. Canis M, Rabischong B, Houlle C, Botchorishvili R, Jardon K, Safi A, et al. Laparoscopic management of adnexal masses: a gold standard? Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2002; 14:423–428.

3. Lee LC, Sheu BC, Chou LY, Huang SC, Chang DY, Chang WC. An easy new approach to the laparoscopic treatment of large adnexal cysts. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 2011; 20:150–154.

4. Eltabbakh GH, Charboneau AM, Eltabbakh NG. Laparoscopic surgery for large benign ovarian cysts. Gynecol Oncol. 2008; 108:72–76.

5. Chapron C, Dubuisson JB, Kadoch O, Capella-Allouc S, Vacher-Lavenu MC. Laparoscopic management of organic ovarian cysts: is there a place for frozen section diagnosis? Hum Reprod. 1998; 13:324–329.

6. Maiman M, Seltzer V, Boyce J. Laparoscopic excision of ovarian neopla subsequently found to be malignant. Obstet Gynecol. 1991; 77:563–565.

7. Kim TJ, Lee YY, Kim MJ, Kim CJ, Kang H, Choi CH, et al. Single port access laparoscopic adnexal surgery. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2009; 16:612–615.

8. Lee YY, Kim TJ, Kim CJ, Park HS, Choi CH, Lee JW, et al. Single port access laparoscopic adnexal surgery versus conventional laparoscopic adnexal surgery: a comparison of peri-operative outcomes. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2010; 151:181–184.

9. Kim WC, Im KS, Kwon YS. Single-port transumbilical laparoscopic-assisted adnexal surgery. JSLS. 2011; 15:222–227.

10. Kim WC, Lee JE, Kwon YS, Koo YJ, Lee IH, Lim KT. Laparoendoscopic single-site surgery (LESS) for adnexal tumors: one surgeon's initial experience over a one-year period. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2011; 158:265–268.

11. Ghezzi F, Cromi A, Bergamini V, Uccella S, Siesto G, Franchi M, et al. Should adnexal mass size influence surgical approach? A series of 186 laparoscopically managed large adnexal masses. BJOG. 2008; 115:1020–1027.

12. Ou CS, Liu YH, Zabriskie V, Rowbotham R. Alternate methods for laparoscopic management of adnexal masses greater than 10 cm in diameter. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2001; 11:125–132.

13. Salem HA. Laparoscopic excision of large ovarian cysts. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2002; 28:290–294.

14. Sagiv R, Golan A, Glezerman M. Laparoscopic management of extremely large ovarian cysts. Obstet Gynecol. 2005; 105:1319–1322.

15. Goh SM, Yam J, Loh SF, Wong A. Minimal access approach to the management of large ovarian cysts. Surg Endosc. 2007; 21:80–83.

16. Vergote I, De Brabanter J, Fyles A, Bertelsen K, Einhorn N, Sevelda P, et al. Prognostic importance of degree of differentiation and cyst rupture in stage I invasive epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Lancet. 2001; 357:176–182.

17. Dembo AJ, Davy M, Stenwig AE, Berle EJ, Bush RS, Kjorstad K. Prognostic factors in patients with stage I epithelial ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 1990; 75:263–273.

18. Timmerman D, Testa AC, Bourne T, Ferrazzi E, Ameye L, Konstantinovic ML, et al. Logistic regression model to distinguish between the benign and malignant adnexal mass before surgery: a multicenter study by the International Ovarian Tumor Analysis Group. J Clin Oncol. 2005; 23:8794–8801.

19. Ekerhovd E, Wienerroith H, Staudach A, Granberg S. Preoperative assessment of unilocular adnexal cysts by transvaginal ultrasonography: a comparison between ultrasonographic morphologic imaging and histopathologic diagnosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001; 184:48–54.

20. Childers JM, Nasseri A, Surwit EA. Laparoscopic management of suspicious adnexal masses. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996; 175:1451–1457.

21. Chong GO, Hong DG, Lee YS. Single-port (OctoPort) assisted extracorporeal ovarian cystectomy for the treatment of large ovarian cysts: compare to conventional laparoscopy and laparotomy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2015; 22:45–49.

22. Yuen PM, Yu KM, Yip SK, Lau WC, Rogers MS, Chang A. A randomized prospective study of laparoscopy and laparotomy in the management of benign ovarian masses. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997; 177:109–114.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download