Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of prostaglandin (PG) E2 for preterm labor induction and to investigate the predictive factors for the success of vaginal delivery.

Methods

A retrospective cohort study was performed in women (n=155) at 24+0 to 36+6 weeks of gestation who underwent induction of labor using a PGE2 vaginal pessary (10 mg, Propess) from January 2009 to December 2015. Success rates of vaginal delivery according to gestational age at induction and incidence of intrapartum complications such as tachysystole and nonreassuring fetal heart rate were investigated. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed to evaluate the predictive factors for success of labor induction.

Results

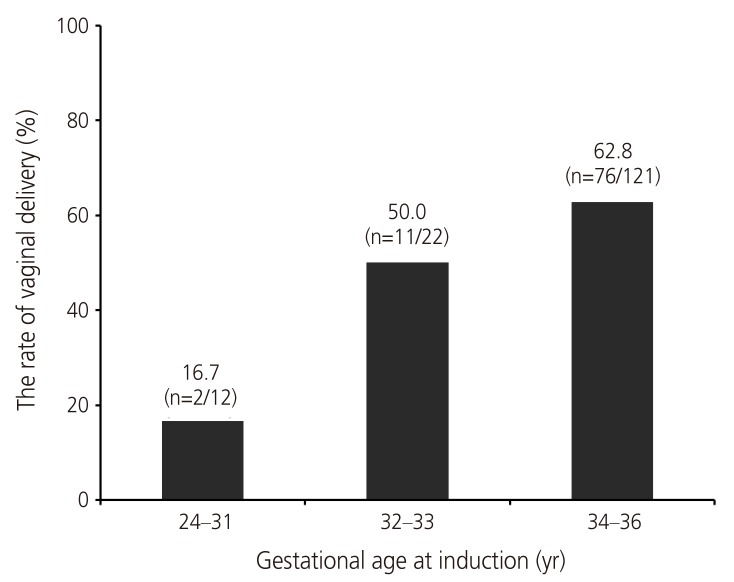

The vaginal delivery rate was 57% (n=89) and the rate of cesarean delivery after induction was 43% (n=66). According to gestational age, labor induction was successful in 16.7%, 50.0%, and 62.8% of patients at 24 to 31, 32 to 33, and 34 to 36 weeks, showing a stepwise increase (P=0.006). There were 18 cases (11%) of fetal distress, 9 cases (5.8%) of tachysystole, and 6 cases (3.8%) of massive postpartum bleeding (>1,000 mL). After adjusting for confounding factors, multiparity (odds ratio [OR], 8.47; 95% confidence interval [CI], 3.10 to 23.14), younger maternal age (OR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.75 to 0.94), advanced gestational age at induction (OR, 1.06; 95% CI, 1.02 to 1.09), rupture of membranes (OR, 11.83; 95% CI, 3.55 to 39.40), and the Bishop score change after removal of PGE2 (OR, 2.19; 95% CI, 1.0 to 4.8) were significant predictors of successful preterm vaginal delivery.

Induction of labor is an increasingly common obstetric procedure, involving about 20% of all pregnant women [1]. Success of labor induction is related to the degree of pre-induction cervical ripening depending on gestational age [23]. Regarding cervical ripening agents or methods, several prostaglandins (PG) including PGE1 and PGE2 (gel, tablet, or pessary type) have been used depending on local availability or the physician's preference. According to a survey performed in our country, the PGE2 vaginal pessary was found to be most frequently used for labor induction [4]. While the efficacy and safety issues of using PGE2 (10 mg) at term pregnancy have been previously demonstrated in many studies [567], few studies have specifically addressed these issues in the context of preterm pregnancy.

Delivery in preterm gestation is indicated in several clinical situations including maternal hypertensive disorder, premature preterm rupture of membranes (PPROM), fetal growth restriction, maternal indication, oligohydramnios, and certain fetal anomalies. Since preterm women, especially those in primiparity, usually have an unfavorable cervix, the rate of cesarean section (CS) due to induction failure is higher than at term [168], suggesting the importance of pre-induction cervical ripening in preterm gestation. On the contrary, possible side effects of PGs such as tachysystole or nonreassuring fetal heart rate may exert more deleterious effects on preterm fetuses [9]. Given these concerns, obstetricians are often reluctant to attempt preterm induction.

Therefore, it is clinically important to investigate the efficacy and safety of cervical ripening agents in preterm pregnancy and to identify elements involved in successful labor induction. In this study, we aimed to examine the success rate and predictive factors for labor induction at preterm gestation (<37 weeks) using the PGE2 vaginal pessary as a cervical ripening agent. We also investigated the incidences of intrapartum complications such as tachysystole and nonreassuring fetal heart rate.

This retrospective study included a total of 155 preterm pregnant women who underwent labor induction with cervical ripening using a 10 mg PGE2 vaginal pessary (Propess, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, West Drayton, UK) from 2009 to 2015 in our institution. The gestational age at labor induction ranged from 24 to 36 complete weeks. We excluded cases with fetal death in utero, multiple gestations, or those with have any contraindications for vaginal delivery (VD).

Demographic data of patients included maternal age, parity, body mass index, and underlying diseases such as hypertension and diabetes mellitus (DM). Clinical characteristics included cervical status (dilatation and effacement), Bishop score, gestational age at induction and delivery, induction to delivery time, rupture of the membranes, delivery mode, indications of induction, reason for CS indication, birth weight, intrapartum complications, postpartum hemorrhage, and neonatal outcomes (Apgar score and neonatal intensive care unit hospitalization).

Induction indications were classified into six categories: hypertensive disorder, PPROM, fetal growth restriction, maternal indication, oligohydramnios, and fetal anomaly. Hypertensive disorder included chronic hypertension, gestational hypertension, and preeclampsia. The maternal indications were DM nephropathy, idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, breast cancer, colon cancer, and history of fetal death in utero. Maternal DM included both overt DM and gestational DM. In cases of fetal anomaly, if the fetal state began to deteriorate due to fetal anomaly, we determined induction of labor.

According to our departmental protocol, women who were admitted for induction were examined by performing vaginal examination (cervical dilation, cervical effacement, cervical consistency, cervical position, and station of fetal presenting part) for Bishop scoring. Fetal heart monitoring was performed prior to PGE2 pessary insertion for one hour. PGE2 insertion into the posterior fornix was performed according to the Bishop score (≤4) and maintained for a maximum of 10 hours. If the Bishop score did not change, PGE2 was inserted again at 24-hour intervals. If uterine contraction was insufficient, augmentation with oxytocin was initiated. The initial oxytocin dose was 5 mU/min (30 mL/hr) and the increment dose was 5 mU/min every 20 minutes as needed. PGE2 was removed in the event of painful uterine contraction, nonreassuring fetal heart rate, or uterine tachysystole (>5 uterine contractions in 10 minutes). Duration from induction to delivery was defined from the time of Propess insertion to the time of delivery. Nonreassuring fetal heart rate was defined as either category II (without adequate reassurance) or category III fetal heart rate tracing. Induction failure was defined as the failure to reach the active phase of labor (cervical dilation of 4 cm or more with regular uterine contractions) after at least 24 hours of oxytocin administration. Progress failure was defined as the arrest of dilation in the active phase or the arrest of descent in the second stage.

Data analysis was used with SPSS ver. 23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Univariate analysis with Student's t-test was performed to measure continuous variable factors and chi square test, Fisher's exact test and linear by linear association analysis were used for categorical variables. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed in order to detect the predictive factors of successful VD. A P-value of <0.05 was considered significant. The study was approved by the hospital's institutional review board (SMC 2016-05-074).

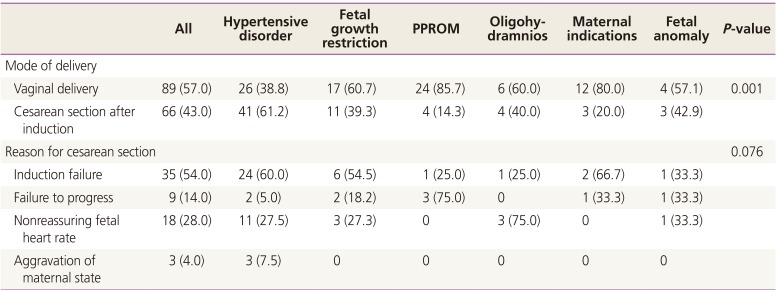

Overall, of the 155 women in our study population who were induced with PGE2, 57% (n=89) underwent VD and 43% (n=66) required CS. The most common indication for labor induction was hypertensive disorder (n=67, 43%), followed by PPROM (n=28, 18%), fetal growth restriction (n=28, 18%), aggravation of maternal medical condition (n=15, 10%), oligohydramnios (n=10, 6%), and fetal anomaly (n=7, 5%).

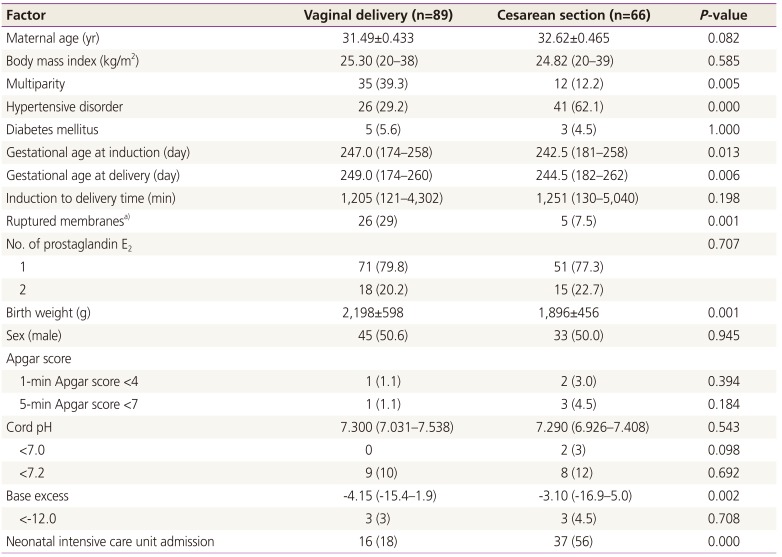

The baseline characteristics of the VD and CS groups were compared (Table 1). As expected, the proportion of multiparous women was significantly higher in the VD group than in the CS group (39.3% vs. 12.2%, P=0.005). The VD rate was significantly higher in patients with ruptured membranes, but lower in patients with concomitant hypertensive disorders. Gestational age at labor induction and neonatal weight in the VD group were significantly higher compared to those in the CS group. As the gestational age at induction progressed, the success of VD increased (P=0.006) (Fig. 1).

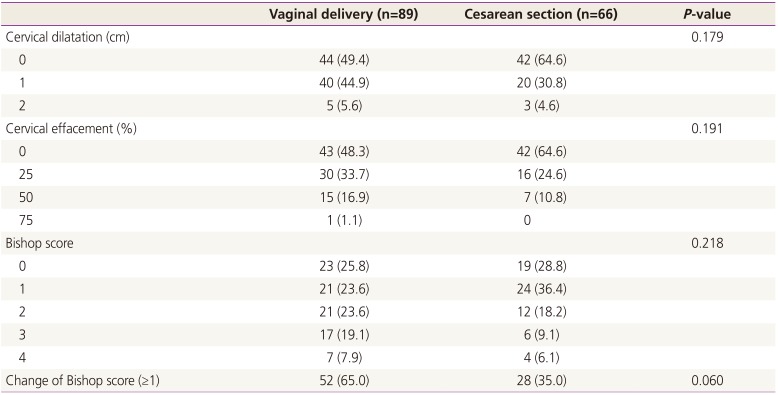

We analyzed cervical status at induction in our study population and compared each parameter between the VD and CS groups (Table 2). The degree of each cervical dilatation or effacement, and Bishop scores at the pre-induction stage were not different between the two groups. However, the change in Bishop scores after the removal of PGE2 seemed to be higher in the VD group than in the CS group (41.6% vs. 56.9%, P=0.06).

We also examined the success rate of VD according to each indication for induction of labor. As shown in Table 3, each induction group went through cesarean delivery after induction for diverse reasons. The major reason for cesarean delivery in the context of hypertensive disorder and fetal growth restriction was induction failure (60.0%, n=24; 54.5%, n=6). The most common reasons for cesarean section in each category of induction indication were failure to progress (PPROM, 75.0%, n=3), non-reassuring fetal heart rate (oligohydramnios, 75.0%, n=3), and induction failure (maternal indication, 66.7%, n=2).

We examined the labor complications such as tachysystole or non-reassuring fetal heart rate in our study population. As a result, there were 18 cases of non-reassuring fetal heart rate (11%) and 9 cases (5.8%) of tachysystole. The incidence of postpartum hemorrhage, which was defined as massive blood loss (>1,000 mL), was 3.8% (n=6), and there were no cases that required transfusion or embolization. Among the neonatal outcomes, there were no differences in Apgar score, neonatal sex and cord PH. between the vaginal and cesarean delivery patients.

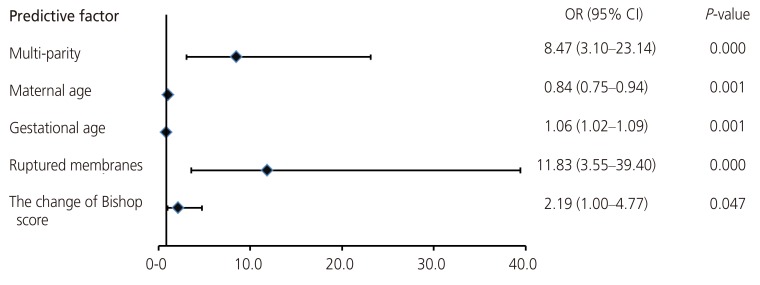

On multivariable logistic regression analysis, multiparity (OR, 8.47; 95% confidence interval [CI], 3.10 to 23.14), maternal age (OR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.75 to 0.94), gestational age at induction (OR, 1.06; 95% CI, 1.02 to 1.09), rupture of membranes (OR, 11.83; 95% CI, 3.55 to 39.40), and change in the Bishop score (OR, 2.19; 95% CI, 1.00 to 4.80) were significant predictors of VD following preterm induction (Fig. 2).

Our study demonstrated that the success rate for VD in preterm induction using PGE2 showed a pattern of stepwise increase according to the gestational age at induction: 16.7% (24 to 31 weeks), 50.0% (32 to 33 weeks), and 62.8% (34 to 36 weeks). In addition to gestational age factor, we identified that multi-parity, younger maternal age, PPROM, and the change in Bishop score after removal of the PGE2 are significant predictive factors for the success of VD in preterm induction. Regarding safety issues, tachysystole after insertion of PGE2 occurred in about 6% of our study population. Although many studies have examined the general use of PGE2 agents for cervical ripening, research focusing specifically on PGE2 in the form of a vaginal pessary has been relatively rare. Thus, our data have contributed important clinical information, particularly regarding preterm pregnancies where delivery is necessary due to maternal or fetal indications.

The optimal method of labor induction in PPROM patients has been controversial. The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists have recommended labor induction in the case of PROM, and suggested caution when using PGE2 in the case of maternal asthma, severe hepatic and renal dysfunction, or glaucoma [3]. However, they have not mentioned any specific contraindication of using PGE2 in PPROM patients. In fact, the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and Ray and Garite [10] refer to the safety and effectiveness of PGE2 in the context of PROM, and a 2004 study of 262 patients with both term and preterm PROM found that there were no apparent maternal or fetal complications in women who were administered PGE2 [11]. In our study, PPROM showed a significantly higher success rate of induction than did the other groups, with no differences in terms of intrapartum complications such as tachysystole or non-reassuring fetal heart rate.

Other studies involving different types and doses of PGE2 have reported on the success rates and safety levels in cases of preterm induction. For example, Abelin Tornblom et al. [6] reported that labor induction at preterm (n=50) with PGE2 gel was successful in 80% of cases and that there were no cases of tachysystole after insertion of PGE2. Notably, that study population consisted of 70% multiparous women. In a large population study by Melamed et al. [12], in which PGE2 (3 mg vaginal tablet) was used for pre-induction cervical ripening at preterm (n=444), a success rate for VD of about 75% was shown, with only one case of tachysystole and a study population of 50% multiparous women. In contrast, we used a different form of PGE2 (10 mg pessary) and found that overall success rate for VD was 56%, with a 6% incidence of tachysystole. The lower success rate of induction in our study population seemed to be associated with the relatively high proportion of primiparous women (70%), which corresponds to previous reports [1314]. Although the rate of tachysystole induced by PGE2 was higher than in previous studies, there was no case of emergent CS due to tachysystole with nonreassuring fetal heart rate in our study population.

Previous studies have demonstrated that degree of cervical ripening, higher gestational age, multi-parity, and lower maternal age are correlated with success of VD, though these studies mostly focused on term pregnancy [215161718]. Indeed, few reports to date have evaluated the predictive factors for labor induction success at preterm gestation. Since preterm induction has a higher failure rate for successful VD than does term induction [19], identifying associated predictors is considered critical in obstetric practice. To that end, we exclusively focused on preterm induction using PGE2 as a cervical ripening agent and demonstrated that multi-parity, younger maternal age, higher gestational age, rupture of membranes, and the change in Bishop score are all significant predictive factors of preterm labor induction success.

It is noteworthy that we presented the success rates of VD and the reasons for CS after induction according to each indication group. Compared to other indication groups, a higher CS rate (61%) was observed in women with hypertensive disorder, which was the most common indication for labor induction among our study population. A higher CS rate in preterm hypertensive women was similarly observed in a study by Blackwell et al. [20], which showed a 54% CS rate at preterm labor induction (gestational age <34 weeks) using a PGE2 gel. In that study, the foremost reason for CS was nonreassuring fetal status, whereas in our study, the chief cause for cesarean delivery in the hypertensive group was induction failure, as opposed to nonreassuring fetal status or aggravation of maternal factors.

Our study may be limited by the fact that we retrospectively collected data from pregnant women who underwent preterm induction, as did previous studies [612]. For example, an individual clinician may opt for CS without first attempting labor induction in some women. Furthermore, the relatively small study population size and higher proportion of late preterm pregnancies (≥34 weeks) could be other weaknesses. Therefore, further studies assessing significant predictive factors and safety aspects associated with labor induction at preterm gestation remain to be conducted.

Typically, when obstetricians need to make a decision regarding delivery method in the context of preterm delivery, they agonize over the efficacy and safety of labor induction. Our study indicated that multiparity, younger maternal age, advanced gestational age, rupture of membranes, and the change in Bishop score were independently associated with the success of preterm labor induction using PGE2. In terms of safety, incidences of tachysystole, nonreassuring fetal status resulting in emergent cesarean delivery, and postpartum bleeding were low overall. Those results might be particularly relevant to consultations with women when premature delivery is deemed necessary.

References

1. Vrouenraets FP, Roumen FJ, Dehing CJ, van den Akker ES, Aarts MJ, Scheve EJ. Bishop score and risk of cesarean delivery after induction of labor in nulliparous women. Obstet Gynecol. 2005; 105:690–697. PMID: 15802392.

2. Hendricks CH, Brenner WE, Kraus G. Normal cervical dilatation pattern in late pregnancy and labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1970; 106:1065–1082. PMID: 5435658.

3. ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins Obstetrics. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 107: Induction of labor. Obstet Gynecol. 2009; 114:386–397. PMID: 19623003.

4. Min JA, Choi SJ, Jung KL, Oh SY, Kim JH, Roh CR. The clinical practice pattern of postterm pregnancy in Korea. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 2007; 50:79–84.

5. Kelly AJ, Kavanagh J, Thomas J. Vaginal prostaglandin (PGE2 and PGF2a) for induction of labour at term. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003; 4:CD003101.

6. Abelin Tornblom S, Ostlund E, Granstrom L, Ekman G. Pre-term cervical ripening and labor induction. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2002; 104:120–123. PMID: 12206923.

7. Carlan SJ, O'Brien WF, Logan S. Serial intravaginal prostaglandin E2 gel cervical ripening in preterm pregnancies. Prostaglandins. 1996; 52:237–246. PMID: 8908623.

8. Moore LE, Rayburn WF. Elective induction of labor. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2006; 49:698–704. PMID: 16885673.

9. Hofmeyr GJ, Gulmezoglu AM. Vaginal misoprostol for cervical ripening and induction of labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003; (1):CD000941. PMID: 12535398.

10. Ray DA, Garite TJ. Prostaglandin E2 for induction of labor in patients with premature rupture of membranes at term. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992; 166:836–843. PMID: 1550149.

11. Ben-Haroush A, Yogev Y, Glickman H, Bar J, Kaplan B, Hod M. Mode of delivery in pregnancies with premature rupture of membranes at or before term following induction of labor with vaginal prostaglandin E2. Am J Perinatol. 2004; 21:263–268. PMID: 15232758.

12. Melamed N, Yogev Y, Hadar E, Hod M, Ben-Haroush A. Preinduction cervical ripening with prostaglandin E2 at preterm. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2008; 87:63–67. PMID: 18158629.

13. Ehrenthal DB, Jiang X, Strobino DM. Labor induction and the risk of a cesarean delivery among nulliparous women at term. Obstet Gynecol. 2010; 116:35–42. PMID: 20567165.

14. Johnson DP, Davis NR, Brown AJ. Risk of cesarean delivery after induction at term in nulliparous women with an unfavorable cervix. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003; 188:1565–1569. PMID: 12824994.

15. Anderson AB, Turnbull AC. Relationship between length of gestation and cervical dilatation, uterine contractility, and other factors during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1969; 105:1207–1214. PMID: 5360251.

16. Yogev Y, Ben-Haroush A, Gilboa Y, Chen R, Kaplan B, Hod M. Induction of labor with vaginal prostaglandin E2. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2003; 14:30–34. PMID: 14563089.

17. Prysak M, Castronova FC. Elective induction versus spontaneous labor: a case-control analysis of safety and efficacy. Obstet Gynecol. 1998; 92:47–52. PMID: 9649091.

18. Lee HR, Kim MN, You JY, Choi SJ, Oh SY, Roh CR, et al. Risk of cesarean section after induced versus spontaneous labor at term gestation. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2015; 58:346–352. PMID: 26430658.

19. Nageotte MP, Dorchester W, Porto M, Keegan KA Jr, Freeman RK. Quantitation of uterine activity preceding preterm, term, and postterm labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988; 158:1254–1259. PMID: 3273360.

20. Blackwell SC, Redman ME, Tomlinson M, Landwehr JB Jr, Tuynman M, Gonik B, et al. Labor induction for the preterm severe pre-eclamptic patient: is it worth the effort? J Matern Fetal Med. 2001; 10:305–311. PMID: 11730492.

Fig. 2

Multiple logistic regression analyses of success of vaginal delivery. OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Table 1

Demographic and clinical characteristic of study patients

Table 2

Cervical status and Bishop score at time of labor induction

Table 3

The success rate of vaginal delivery and reason for cesarean section according to indication of preterm delivery

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download