Abstract

We report a case of a fetus with an ultrasonography diagnosis of a neuroblastoma during a routine third trimester fetal scan, which presented as a hyperechogenic nodule located above the right kidney. No other abnormalities were found in the ultrasonography scan; however, the follow-up ultrasonography during the 36th week of gestation revealed that the lesion had doubled in size. At the same time, magnetic resonance imaging demonstrated a round mass in the topography of the right adrenal gland with a low signal on T1-weighted images and slightly high signal on T2-weighted images, causing a slight inferior displacement of the kidney. The liver had enlarged and had heterogeneous signal intensity, predominantly hypointense on T2-weighted sequences. Based on these findings, a diagnosis of congenital adrenal neuroblastoma with liver metastases was suggested. A newborn male was delivered by cesarean section 2 weeks later. The physical examination of the neonate revealed abdominal distention and hepatomegaly. The infant had a clinical follow-up in which no surgical or medical intervention was required. At 5 months of age, the infant was asymptomatic with a normal physical examination.

Neuroblastoma is a poorly differentiated embryonal nerve cell tumor. Though most commonly found in the adrenal gland (90%), it may also be found in the posterior mediastinum or along the sympathetic neural chain [12]. Congenital neuroblastoma is the second most common tumor occurring in the neonatal period, corresponding to 20% of all congenital tumors [3]. The incidence ranges from 1 in 10,000 to 1 in 100,000 of all live births [456]. According to some studies, a deletion at the distal portion of the short arm of chromosome 1 (1p36.1-p36.2 or 1p34-p35) is related to the presence of a neuroblastoma [78].

Prenatally diagnosed neuroblastoma involves the adrenal gland in the vast majority of cases, and the cases of in utero metastases have been described [29]. The most common sites of distant metastases are the fetal liver, placenta, retroperitoneal nodes, paraspinal region, bone, skin, and umbilical cord [59]. Ultrasonography (USG) can be used to determine the size, location, and sonographic features of the tumor and to detect metastases. Fetal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be a complementary tool [1011] to confirm the anatomic location and exclude adrenal hemorrhage and is useful for staging and evaluating metastases [10].

Here we report a case of a fetus with a sonographic third trimester diagnosis of a hyperechogenic nodule above the right kidney during the 36th week of gestation. The liver was enlarged, and MRI showed a heterogeneous signal intensity, based on which a diagnosis of congenital adrenal neuroblastoma with liver metastases was suggested. We also present the follow-up of the fetus at 5 months of age.

A 25-year-old woman (gravida 1, para 0) was referred to our clinic for a routine USG during the 29th week of gestation. Her past medical history was uneventful; in particular, there was no evidence of hypertension. The USG examination revealed a hyperechogenic nodule measuring 1.4 cm in diameter, located above the right kidney. Doppler USG was used, and there was no sign of peripheral vascularization to the lesion. The amniotic fluid volume was normal and the fetal development was appropriate for the gestational age. Follow-up USG was performed during the 36th week of gestation. The lesion had doubled in size (3.3 cm in diameter), and the liver had enlarged, showing a heterogeneous texture. Fetal MRI was also performed on the same day. A round mass was identified in the topography of the right adrenal gland with a low signal on T1-weighted sequences and slightly high signal on T2-weighted sequences, measuring 4.2×3.4×4.1 cm, causing a slight inferior displacement of the kidney (Fig. 1). The liver was enlarged and the signal intensity was heterogeneous, predominantly hypointense on T2-weighted sequences. Based on these findings, the diagnosis of congenital adrenal neuroblastoma with liver metastases was suggested.

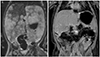

Cesarean section was performed during the 38th week of gestation. A male infant, weighing 2,890 g, was delivered with Apgar scores of 9 at both 1st and 5th minute. A physical examination of the neonate, performed immediately after delivery, demonstrated abdominal distention and hepatomegaly. At 5 weeks of age, a follow-up MRI was performed. It revealed a poorly defined mass in the right adrenal gland measuring 3.6×3.3×2.2 cm with heterogeneous signal intensity, predominantly hypointense on T1- and hyperintense on T2-weighted sequences, with heterogeneous contrast enhancement and a central area of cystic degeneration. The liver showed a huge enlargement (extending from the right iliac fosse up to the left hypochondria), lobulated contours, multiple nodular lesions, a low signal on T1-weighted images and high signal on T2-weighted images, and enhancement after gadolinium administration (Fig. 2A).

The infant had a clinical follow-up with no surgery or drugs because of the abdominal location. At 5 months of age, he was asymptomatic with a normal physical examination. The follow-up MRI showed the right adrenal mass with the same signal characteristics as recorded previously but with an significant decrease in size (2.0×1.1×0.9 cm). The liver showed no focal lesions, presented with normal size, contours, and signal intensity, as well as homogeneous gadolinium enhancement (Fig. 2B).

As reported in the literature, prenatal neuroblastoma is difficult to diagnose [124]. It has been described as "echogenic" or "heterogeneous" in the USG examination, and occasionally, its appearance can be purely cystic or complex [12]. During the USG examination, a neuroblastoma should be considered when any suprarenal mass is observed [911]. Differential diagnoses include subdiaphragmatic cystic adenomatoid malformation, subdiaphragmatic extralobar pulmonary sequestration, duplicated renal collecting system, or adrenal hemorrhage [4612]. Subdiaphragmatic extralobar pulmonary sequestration is more common than neuroblastoma and is most frequently echogenic, left-sided, and can be identified in the second trimester. Neuroblastoma, on the other hand, is most frequently cystic, right-sided, and is usually identified in the third trimester. Color flow mapping and Doppler flow studies may also be helpful to differentiate between these conditions as the neuroblastoma does not have a single feeding vessel [12].

According to the International Neuroblastoma Staging System, this case was classified as stage 4S (also called "special" neuroblastoma) [13]. An important characteristic of the 4S stage neuroblastoma is that the tumor is usually associated with a good prognosis [311]. The detection of liver metastasis is important because it confirms, in several cases, the diagnosis of a neuroblastoma [11]. Typically, the course of a pregnancy is not altered when a fetal neuroblastoma is detected prenatally using USG and/or fetal MRI. For tumors with favorable biological and clinical features, many doctors advise follow-up without any treatment, reserving surgical treatment for cases with poor prognosis [6].

USG is a useful screening tool for the evaluation of abdominal masses in the fetus [11]. The typical sonographic appearance of a neuroblastoma is as a solid extrarenal mass, displacing the kidney inferiorly and laterally; however, cystic change may be the predominant feature [211]. Hyperechoic areas may be observed with microcalcifications, and distal acoustic shadowing may be produced by larger clumps of calcium. Small and irregular areas are usually related to hemorrhage or necrosis [4].

MRI can be a complementary tool in cases where liver metastasis is suspected [1011] to help confirm the anatomic location and exclude adrenal hemorrhage and is useful for staging and evaluating metastases [10]. Signal characteristics vary depending on cystic or solid composition. MRI T2-weighted images reveal a marked signal in the cystic composition and a moderate signal in the solid composition of a neuroblastoma. In neonates and children, this tumor usually exhibits heterogeneous low signal intensity on T1-weighted images and a high signal intensity on T2-weighted images. Intratumoral hemorrhage areas typically have a high signal intensity on T1-weighted images, and cystic changes have a high signal intensity on T2-weighted images [10]. Furthermore, liver metastases may take two forms: diffuse infiltration (observed in infants with stage 4S disease, which can be overlooked on computed tomography as it may uniformly increase the parenchymal attenuation) and focal hypoenhancing masses [14].

In summary, we have described the evolution of a case of congenital adrenal neuroblastoma with liver metastases, from the diagnosis in the third trimester of pregnancy until the regression of the lesion at 5 months of age, using USG and MRI examinations. USG is the imaging method of choice for the diagnosis of fetal tumors, and MRI is an important complementary method to confirm the liver metastasis. In this case, a multidisciplinary team comprising specialists in fetal medicine, pediatric radiology, neonatology, obstetrics, and pediatric oncology was important for the parental counseling, delivery, and choice of conservative postnatal management. This case report is an example of the excellent prognosis of an adrenal 4S stage neuroblastoma without surgical and chemotherapy treatment and shows the usefulness of USG and MRI in the diagnosis and prognosis evaluation.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

(A) Ultrasonography in axial view of fetal abdomen identifying a hyperechogenic image above the right kidney (arrow) at 29th week of gestation. (B) Fetal magnetic resonance imaging T2-weighted (axial view) showing an increased and heterogeneous liver (*) and a round mass with lightly high signal in the right adrenal (arrow) at 36th week of gestation.

References

1. Delahaye S, Doz F, Sonigo P, Saada J, Mitanchez D, Sarnacki S, et al. Prenatal diagnosis of dumbbell neuroblastoma. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008; 31:92–95.

2. DeMarco RT, Casale AJ, Davis MM, Yerkes EB. Congenital neuroblastoma: a cystic retroperitoneal mass in a 34-week fetus. J Urol. 2001; 166:2375.

3. Koksal Y, Varan A, Kale G, Tanyel FC, Buyukpamukcu M. Bilateral adrenal cystic neuroblastoma with hepatic and splenic involvement in a newborn. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2005; 27:670–671.

4. Chen CP, Chen SH, Chuang CY, Lee HC, Hwu YM, Chang PY, et al. Clinical and perinatal sonographic features of congenital adrenal cystic neuroblastoma: a case report with review of the literature. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1997; 10:68–73.

5. Lee SY, Chuang JH, Huang CB, Hsiao CC, Wan YL, Ng SH, et al. Congenital bilateral cystic neuroblastoma with liver metastases and massive intracystic haemorrhage. Br J Radiol. 1998; 71:1205–1207.

6. Luis AL, Martinez L, Hernandez F, Sastre A, Garcia P, Queizan A, et al. Congenital neuroblastomas. Cir Pediatr. 2004; 17:89–92.

7. Amler LC, Bauer A, Corvi R, Dihlmann S, Praml C, Cavenee WK, et al. Identification and characterization of novel genes located at the t(1;15)(p36.2;q24) translocation breakpoint in the neuroblastoma cell line NGP. Genomics. 2000; 64:195–202.

8. Koesters R, Adams V, Betts D, Moos R, Schmid M, Siermann A, et al. Human eukaryotic initiation factor EIF2C1 gene: cDNA sequence, genomic organization, localization to chromosomal bands 1p34-p35, and expression. Genomics. 1999; 61:210–218.

9. Sul HJ, Kang Dy. Congenital neuroblastoma with multiple metastases: a case report. J Korean Med Sci. 2003; 18:618–620.

10. Elsayes KM, Mukundan G, Narra VR, Lewis JS Jr, Shirkhoda A, Farooki A, et al. Adrenal masses: mr imaging features with pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2004; 24:Suppl 1. S73–S86.

11. Forman HP, Leonidas JC, Berdon WE, Slovis TL, Wood BP, Samudrala R. Congenital neuroblastoma: evaluation with multimodality imaging. Radiology. 1990; 175:365–368.

12. Daltro PA, Werner H. Fetal MRI of the chest. In : Lucaya J, Strife JL, editors. Pediatric chest imaging. Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag;2008. p. 397–416.

13. Castel V, Garcia-Miguel P, Canete A, Melero C, Navajas A, Ruiz-Jimenez JI, et al. Prospective evaluation of the International Neuroblastoma Staging System (INSS) and the International Neuroblastoma Response Criteria (INRC) in a multicentre setting. Eur J Cancer. 1999; 35:606–611.

14. Lonergan GJ, Schwab CM, Suarez ES, Carlson CL. Neuroblastoma, ganglioneuroblastoma, and ganglioneuroma: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2002; 22:911–934.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download