Abstract

Objective

The objective of this study was to assess the effect of folic acid and multivitamin use during pregnancy on the risk of developing of hypertensive disorder of pregnancy.

Methods

Two reviewers independently determined all prospective cohort study, retrospective cohort study, large population based cohort study, retrospective secondary analysis, and double blinded, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial published using PubMed Medline database, KERIS (Korea Education and Research Information Service), Scopus, and the Cochrane Central Register of controlled trials comparing before conception throughout pregnancy intake oral multivitamin containing folic acid or folic acid alone. Meta-analyses were estimated with odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using random effect analysis according to heterogeneity of studies.

Results

Data from six effect sizes from six studies involving 201,661 patients were enrolled. These meta-analyses showed multivitamin containing folic acid or folic acid alone was not significantly effective in reducing gestational hypertension or preeclampsia incidence (odds ratio, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.81 to 1.03) than the placebo. And the difference of effective sizes of preeclampsia and gestational hypertension according to two dependent variables, multivitamin and folic acid were not significant, respectively (point estimate, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.46 to 0.96).

Hypertensive disorder of pregnancy is one of the most important cause of maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality, accounting for about 5% to 10% of pregnancies [12]. But, the pathogenesis of preeclampsia and gestational hypertension remain uncertain. And its prevention is very important, but really difficult [34]. The role of maternal intake of some nutrition before conception or early pregnancy to throughout pregnancy in influencing the risk of developing hypertensive disorder of pregnancy is unclear. Some studies have observed a significant elevation of serum homocysteine among women with gestational hypertension or preeclampsia. Hyperhomocysteinemia can be corrected by folic acid intake [567]. Were folic acid intake to decrease the incidence of gestational hypertension or preeclampsia, it would have very important clinical significance in prevention of hypertensive disorder of pregnancy. Folic acid use studies are disagree with some indicating good effects [8910] and others indicating no benefits [111213].

The objective of our study was to examine whether antenatal multivitamin containing folic acid or folic acid alone use is associated with favorable effects on hypertensive disorder of pregnancy.

We developed a search strategy to use MeSH (Medical Subject Heading) terms and free key words and text words related to "hypertensive disorder of pregnancy," "preeclampsia," "gestational hypertension," "pregnancy-induced hypertension," "folic acid," and "multivitamin containing folic acid." We searched these terms from PubMed Medline, KERIS (Korea Education and Research Information Service), Scopus, and the Cochrane Central Register of controlled trials from 1980 through February 2015 database without language restrictions. The inclusion criteria were all published prospective, retrospective, and large population based cohort study, retrospective secondary analysis, and double blinded, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial comparing multivitamin containing folic acid or folic acid alone intake with placebo, while publications in abstract form alone were excluded. Data abstraction was completed by two independent investigators. Each independently abstracted data from each study and analyzed data separately.

Pregnant women with hypertensive disorder of pregnancy consisting of gestational hypertension and preeclampsia were included. The diagnosis of gestational hypertension is made in women whose blood pressures reach 140/90 mmHg or greater for the first time after pregnancy. Preeclampsia was defined as having a blood pressure of 140/90 or 30/15 mmHg above baseline with proteinuria of +1 or +2 on dipstick test or 300 mg in 24-hour urine collection in women greater than 20 week of gestation.

Differences were reviewed, and further resolved by common review of the entire data set. Data abstracted included number of study patients, number of patients in intervention and control groups, dosage and gestational weeks of administration of folic acid, the incidence of preeclampsia and gestational hypertension. For studies that did not stratify data, composite data were extracted. When possible, authors of included trials were contacted for missing data. The risk of bias in each included study was assessed by using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Seven domains related to risk of bias were assessed in each included trial since there is evidence that these issues are associated with biased estimates of treatment effect: 1) random sequence generation, 2) allocation concealment, 3) blinding of participants and personnel, 4) blinding of outcome assessment, 5) incomplete outcome date, 6) selective reporting, and 7) other bias. Review authors' judgments were categorized as low, high, or unclear risk of bias.

Meta-analyses were performed with random effects models according to the heterogeneity of studies. The completed analyses were then compared, and any difference was resolved with review of entire data set and independent analysis. Statistical heterogeneity (P-value of the Cochrane Q statistic and Higgins I2 statistic <0.1) (Q [6]=23.271, P<0.01).

Heterogeneity between results, interpreted as the proportion of the total variation in estimated risk ratios that is due to between-study heterogeneity instead of chance, was assessed with I2, and I2 values of 25%, 50%, and 75% corresponding to low, moderate, and high levels of heterogeneity, respectively. In subgroup analysis, the random effects model was chosen because we could not remove the heterogeneity of subgroups.

All effect sizes were calculated through Comprehensive Meta-analysis (CMA) 2.0 software (Biostat, Englewood, NJ, USA). Meta-analyses were estimated with odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using random effect analysis according to heterogeneity of studies. P-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The meta-analysis was performed following the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses) statement. This study had no funding source.

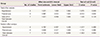

Twenty-one trials on multivitamin containing folic acid or folic acid alone intake during pregnancy and the risk of gestational hypertension and preeclampsia were identified. Seven studies evaluating the effect of multivitamin containing folic acid or folic acid alone intake in the development of gestational hypertension and preeclampsia during pregnancy or before conception throughout pregnancy were identified. Six trials that met inclusion criteria for this meta-analysis were analyzed. No similar systematic review was found. Fig. 1 shows the flow diagram of information through the different phases of the review. The quality of a randomized controlled trial included in our meta-analysis was assessed by the Cochrane Collaboration's tool. All studies had low risk of bias in incomplete outcome data and selective reporting. Table 1 shows the summary of characteristics of enrolled studies included meta-analyses [8910111415].

Fig. 2 shows funnel plot for assessing publication bias for the risk of gestational hypertension and preeclampsia; it looked apparent that the funnel plot in Fig. 2 was biased. We performed additional tests to check whether this bias is potential threat to distort the overall result. With Begg and Mazumdar's rank correlation approach, Kendall's tau is -0.571 which was not statistically significant (P>0.05). These results indicated that the bias was unlikely in this data. Furthermore, we scrutinized what it would be like if the data was perfectly symmetric with Duval and Tweedie's trim and fill approach. Four virtual studies were added to make the data symmetric. The adjusted estimates was 1.026 which was not that statistically deviant from the observed value 1.021, which suggested that the given estimates were reliable and constant regardless of the adjustment (Fig. 2).

Data from seven effect sizes from six studies involving 201,661 patients were enrolled. These meta-analyses showed multivitamin containing folic acid or folic acid alone was not significantly effective in reducing gestational hypertension or preeclampsia incidence (OR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.81 to 1.03) than the placebo (Tables 2, 3) [8910111415].

And the difference of effective sizes of preeclampsia and gestational hypertension according to two dependent variables, multivitamin and folic acid was not significant, respectively (point estimate, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.52 to 0.99) (Table 4).

This meta-analysis of pooled data of seven studies shows that multivitamin containing folic acid or folic acid alone was not significantly effective in reducing gestational hypertension or preeclampsia incidence compared to controls. Various strategies used to prevent occurrence of preeclampsia or modify preeclampsia severity have been evaluated for many years. But, none of these antioxidants, multivitamin, and exercise have been found to be convincingly and reproducibly effective. The benefits of folic acid intake have so far been focused on the preventive effects on neural tube defects and mega-loblastic anemia [1617]. The other potential benefits of folic acid on maternal and fetal health beyond its effect on neural tube defects and megaloblastic anemia combined with the lack of scientific evidence. So, these studies have created a confusion in folic acid intake throughout pregnancy to many clinicians. Folic acid use studies are inconsistent. Our results of meta-analyses from six effect sizes from six studies involving 201,661 patients showed multivitamin containing folic acid or folic acid alone was not significantly effective in reducing gestational hypertension or preeclampsia incidence than the placebo. These meta-analyses are the first study to examine whether antenatal multivitamin containing folic acid or folic acid alone use is associated with favorable effects on developing of the gestational hypertension or preeclampsia.

Concerning the study's limitation, the periods of maternal consumption of folic acid intake were different. In four studies, folic acid was supplemented before conception to 14–20 weeks. Other three studies, folic acid was used from 2 to 3 months before conception throughout pregnancy. Thus, these findings may not be representative of the effects of folic acid during both the preconception period and the all pregnancy periods. The amount of folic acid supplemented to mother was various from 0.4 to 1.0 mg. Also, these analyses did not include the study of high dose folic acid more than 4 mg. The women intake with multivitamin containing thiamine, riboflavin, vitamin C, vitamin 6, vitamin 12, and vitamin E were enrolled this study. Nonetheless, these results from reliable statistical analyses are clinically meaningful, and they can offer useful information about the association between folic acid intake and hypertensive disorder of pregnancy. These analyses indicate folic acid use may not be helpful in reducing the incidence of gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. According to Gui et al. [18], Larginine intake was superior to placebo in lowering blood pressure and lengthen duration of pregnancy period in patients with gestational hypertension or preeclampsia. Whether arginine intake has a benefit in women with hypertensive disorders needs further large scale, multicenter studies.

Also, folic acid has many other useful effects on pregnancy. Considering the additional protective effect of folic acid against other adverse pregnancy outcomes, folic acid intake should be recommended at least from 2 to 3 months before conception and throughout pregnancy. To clarify the optimal amount and duration of folic acid use for best improving maternal and neonatal outcomes, further more studies are warranted in the future.

References

1. Leeman L, Fontaine P. Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Am Fam Physician. 2008; 78:93–100.

2. Cifkova R. Why is the treatment of hypertension in pregnancy still so difficult? Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2011; 9:647–649.

3. Sibai BM. Diagnosis and management of gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2003; 102:181–192.

4. Report of the National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000; 183:S1–S22.

5. Yanez P, Vasquez CJ, Rodas L, Duran A, Chedraui P, Liem KH, et al. Erythrocyte folate content and serum folic acid and homocysteine levels in preeclamptic primigravidae teenagers living at high altitude. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2013; 288:1011–1015.

6. Tang Z, Buhimschi IA, Buhimschi CS, Tadesse S, Norwitz E, Niven-Fairchild T, et al. Decreased levels of folate receptor-β and reduced numbers of fetal macrophages (Hofbauer cells) in placentas from pregnancies with severe pre-eclampsia. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2013; 70:104–115.

7. Mujawar SA, Patil VW, Daver RG. Study of serum homocysteine, folic Acid and vitamin b(12) in patients with preeclampsia. Indian J Clin Biochem. 2011; 26:257–260.

8. Wen SW, Chen XK, Rodger M, White RR, Yang Q, Smith GN, et al. Folic acid supplementation in early second trimester and the risk of preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008; 198:45.e1–45.e7.

9. Bodnar LM, Tang G, Ness RB, Harger G, Roberts JM. Periconceptional multivitamin use reduces the risk of preeclampsia. Am J Epidemiol. 2006; 164:470–477.

10. Hernandez-Diaz S, Werler MM, Louik C, Mitchell AA. Risk of gestational hypertension in relation to folic acid supplementation during pregnancy. Am J Epidemiol. 2002; 156:806–812.

11. Li Z, Ye R, Zhang L, Li H, Liu J, Ren A. Folic acid supplementation during early pregnancy and the risk of gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. Hypertension. 2013; 61:873–879.

12. Ray JG, Mamdani MM. Association between folic acid food fortification and hypertension or preeclampsia in pregnancy. Arch Intern Med. 2002; 162:1776–1777.

13. Theriault S, Giguere Y, Masse J, Lavoie SB, Girouard J, Bujold E, et al. Absence of association between serum folate and preeclampsia in women exposed to food fortification. Obstet Gynecol. 2013; 122(2 Pt 1):345–351.

14. Kim MW, Ahn KH, Ryu KJ, Hong SC, Lee JS, Nava-Ocampo AA, et al. Preventive effects of folic acid supplementation on adverse maternal and fetal outcomes. PLoS One. 2014; 9:e97273.

15. Merchant AT, Msamanga G, Villamor E, Saathoff E, O'brien M, Hertzmark E, et al. Multivitamin supplementation of HIV-positive women during pregnancy reduces hypertension. J Nutr. 2005; 135:1776–1781.

16. Talaulikar VS, Arulkumaran S. Folic acid in obstetric practice: a review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2011; 66:240–247.

17. Osterhues A, Ali NS, Michels KB. The role of folic acid fortification in neural tube defects: a review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2013; 53:1180–1190.

18. Gui S, Jia J, Niu X, Bai Y, Zou H, Deng J, et al. Arginine supplementation for improving maternal and neonatal outcomes in hypertensive disorder of pregnancy: a systematic review. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst. 2014; 15:88–96.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download