Abstract

Objective

The aims of the present study were to investigate the women's perspective on influenza infection and vaccination and to evaluate how they influence vaccine acceptability, in Korean women of childbearing age.

Methods

This was a prospective study by random survey of women of childbearing age (20 to 45 years). They were asked to complete a questionnaire assessing their knowledge, attitudes and acceptability of influenza vaccination before and during pregnancy. This study utilized data from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) between 2008 and 2012, to analyze the recent influenza vaccination trends.

Results

According to KNHANES (2008-2012), influenza vaccination rates in women of childbearing age have increased up to 26.4%, after 2009. The questionnaire was completed by 308 women. Vaccination rate during pregnancy or planning a pregnancy was 38.6%. The immunization rate increased significantly with the mean number of correct answers (P<0.001). Women who received influenza vaccination were more likely to be previously informed of the recommendations concerning the influenza vaccination before or during pregnancy, received the influenza vaccination in the past, and of the opinion that influenza vaccination is not dangerous during pregnancy, with odds ratios of 14.6 (95% confidence interval [CI], 6.44 to 33.33; P<0.0001), 3.6 (95% CI, 1.84 to 6.97; P=0.0002) and 2.7 (95% CI, 1.34 to 5.47; P=0.0057).

Conclusion

Influenza vaccination rate in women of childbearing age has increased in this study and national data. More information and recommendation by healthcare workers, especially obstetricians, including safety of vaccination, might be critical for improving vaccination rate in women of childbearing age.

Influenza (flu) is a major cause of worldwide morbidity and mortality. It has been reported that pregnant women have higher rates of infection and hospital admission, and are at increased risk of maternal complications and serious neonatal outcomes, such as neonatal intensive care unit admission, increased rates of stillbirth and preterm birth [1,2,3]. Vaccination is the primary method of prevention against influenza infection and its resulting complications [4,5]. One additional potential benefit of maternal vaccination is a reduction in the risk of disease through transplacental antibody transfer in infants during the first several months [5,6].

Influenza immunization has thus been routinely recommended in the US since 2004 and the World Health Organization since 2005, at any time during pregnancy [7,8]. Despite existing recommendations and data on the effectiveness and safety of vaccine, the influenza vaccine is underused in most countries.

The influenza A (H1N1) 2009 pandemic was responsible for at least 18,449 reported deaths globally [9], of which pregnant women represented 4% to 13% [10,11]. However, maternal influenza immunization rate in Korea were very low in the previous studies [12,13]. The Korean Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC) firstly published 'Guidelines of vaccination for adult' at 2012, wherein it recommended that pregnant women and women who are planning pregnancy at flu season should have priority for influenza vaccination [14].

The awareness of influenza vaccination for women of childbearing age is expected to improve, but there is still limited data evaluating the perception of women of childbearing age on influenza vaccination. The aims of the present study were to investigate the women's knowledge and beliefs towards influenza infection and vaccination and to evaluate how they influence vaccine acceptability during pregnancy, by analyses of recent influenza vaccination trends in Korean women of childbearing age.

This study utilized data from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) between 2008 and 2012. The KNHANES was conducted by KCDC to examine the general health and nutritional status of Koreans. To select a representative sample of the Korean population, a stratified three-stage clustered probability design (local district, enumeration district, and household) was utilized. To elucidate the influenza vaccination rate in women of childbearing age in Korea, we analyzed 8,518 women participants to the KNHANES aged between 20 and 45 years, with known influenza vaccination status. We analyzed the KNHANES data considering the weight values, according to the complex sampling design.

This was a prospective study by random survey of women of childbearing age (20 to 45 years) in Seoul and the surrounding area (25,000,000 inhabitants). This study was conducted by means of a self-administered close-ended questionnaire which was distributed by the medical staff in outpatient clinics of obstetrics and gynecology departments in the five primary, secondary, or tertiary hospitals, between October 2012 and July 2013. This study and waiver of written consent was approved by institutional review boards of Catholic University of Korea. Among women of childbearing age who visited the hospitals, women who were planning a pregnancy within 3 months, being pregnant, or in postpartum 6 months were included in this study. This study and waiver of written consent was approved by institutional review boards. They were asked to fill in a questionnaire in the clinic, assessing their knowledge, attitudes and acceptability of Tdap vaccination. No exclusion criterion was applied. Willingness to complete the questionnaire was the only requirement to participate in the study. However, women who were planning pregnancy were surveyed between October 2012 and December 2012, to consider flu season. Postpartum women were asked about vaccination during pregnancy. They were required to complete a questionnaire assessing their knowledge, attitudes and acceptability of influenza vaccination before and during pregnancy.

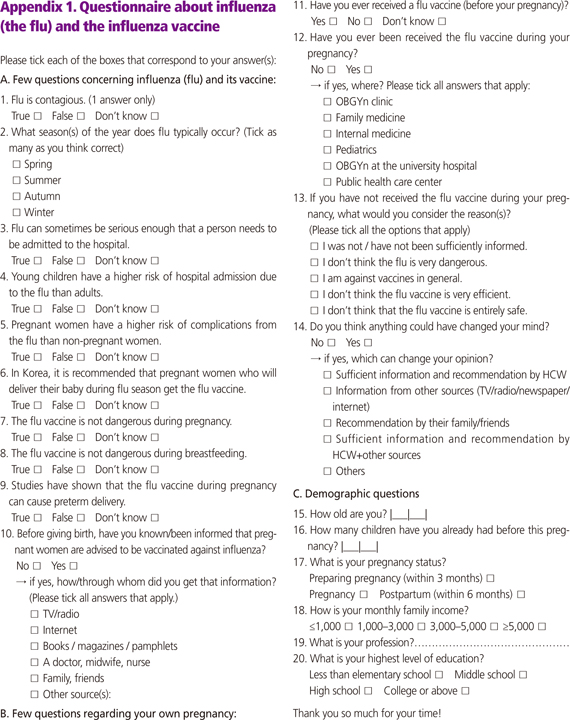

The questionnaire by Blanchard-Rohner et al. [15] in Switzerland, adapted from a previous questionnaire established and validated by a Canadian group [16,17], was applied with permission. It consisted of 21 questions grouped into 3 sections (Appendix 1). Section 1 was intended to evaluate the factual knowledge of influenza in general and in specific risk groups (pregnant women and young children), influenza vaccine, its safety and its recommendations during pregnancy. Section 2 contained questions about the pregnancy and the influenza vaccination status. Section 3 consisted of demographic questions (age, education level, etc.). The English questionnaire was translated in Korean. It was pretested for clarity and comprehensiveness with 3 to 5 women without medical background.

The primary outcome variable was each woman's response to influenza vaccination, during pregnancy, or planning a pregnancy within 3 months, during the flu season. We analyzed the frequency of each response in relation to all variables including demographic characteristics, knowledge, attitude, and risk perception in this study. Chi-square test, Fisher's exact test, or t-test were used to identify significant associations between women's vaccination and their survey responses. The variables with P<0.10 in univariate analyses, were entered into the stepwise multiple logistic regression analysis to identify factors associated with influenza vaccination, planning or during pregnancy. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS ver. 12.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) . A P-value of 0.05 or less was considered significant.

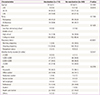

From the KNHANES (2008-2009), influenza vaccination rates in women of childbearing age were less than 20% (Fig. 1). Since 2010, vaccination rate showed increasing tendency up to 26.4% at 2012 KNHANES.

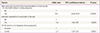

During the study period, the complete survey response rate for individuals who agreed to participate was 97.2% (308/317). Demographic characteristics were presented in Table 1. The median age was 32.2±4.1 years and most women (99.0%) received more than high school education level. Two hundred fifty-five women (84.1%) were in ongoing pregnancy, 127 women (41.2%) were housewives and 49 women (15.9%) were health care workers. Vaccination rate during pregnancy or planning a pregnancy was 38.6%. Groups were separated according to the influenza vaccination during pregnancy or planning a pregnancy. There was no significant difference among groups in mean age, parity, education level, monthly family income level, and occupation. However, women aged <25 years old and >35 years old, and women who were planning a pregnancy and were in postpartum were significantly higher in the non-vaccination group (P=0.0015 and P<0.0001, respectively).

A summary of the questions with the corresponding percentage of correct answers were given in Table 2, with a comparison between vaccinated and non-vaccinated women. Significant differences were found between women who received influenza vaccination in 1) perceived risk of hospitalization in young children infected by influenza (P=0.0116), 2) awareness about recommendation by Korean government about influenza vaccination, during pregnancy (P<0.0001), and 3) concern about safety of influenza vaccination during pregnancy and breastfeeding (P<0.0001 and P=0.0002, respectively), including risk of preterm birth by vaccination (P=0.0002). We observed a higher proportion of correct answers in vaccinated than non-vaccinated women concerning the risks of influenza complications during pregnancy and the existence of a recommendation for pregnant women. The immunization rate increased significantly with the mean number of correct answers (P<0.001)

Information sources with respect to influenza vaccination were summarized in Table 3. More vaccinated women had been previously informed and previously received influenza vaccination in the past (P<0.0001, respectively). More than 60% of vaccinated women received influenza vaccination in obstetric department of clinics or university hospital. Main reasons for non-vaccination were insufficient information (61.2%) and safety concern about influenza vaccination (26.1%). To change opinion in the non-vaccinated group, sufficient information and recommendation by health care workers was considered as the most important factor (47.8%).

The variables with P<0.10 in univariate analyses, were entered into the stepwise multiple logistic regression analysis. The variables with P<0.10 were pregnancy status, monthly family income, knowledge items of 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9, number of correct answers, previous information about recommendations concerning the flu vaccination before or during pregnancy, and past experience about flu vaccination. In the stepwise multiple logistic regression model, women who received influenza vaccination were more likely to be previously informed of the recommendations concerning the influenza vaccination before or during pregnancy; have received influenza vaccination in the past; and think that influenza vaccination is not dangerous during pregnancy; with odds ratios of 14.6 (95% confidence interval [CI], 6.44 to 33.33; P<0.0001), 3.6 (95% CI, 1.84 to 6.97; P=0.0002) and 2.7 (95% CI, 1.34 to 5.47; P=0.0057) (Table 4).

Between 2008 and 2012, influenza vaccination rate in women of childbearing age from the analysis data of the KNHANES has increased since 2010. In this prospective study, vaccination rate during pregnancy or planning a pregnancy was 38.6%, which was much higher than previous studies [12,13]. In 2009, while undergoing an influenza pandemic, the recognition of influenza vaccination for women of childbearing age was expected to improve. It might also have lead to the recognition that obstetricians should recommend influenza vaccination. However, this study comprised a relatively high percentage of women who were health care workers and might have thus affected the vaccination rate. In Korea, an influenza epidemic usually occurs from October to April of the following year, with the peak of the epidemic usually in December and January. The basic elements for influenza prevention and control in medical institutions include the following [18]: influenza vaccination, adherence to precautions, influenza surveillance, infection control according to the environment and facilities of the institution, use of prophylactic and therapeutic antiviral agents, education of patients, guardians, and medical staff.

Vaccination is the most effective way to prevent influenza, and pregnant women are included in priority subjects for vaccination. Additionally, KCDC included women planning a pregnancy during flu season as priority subjects and a recent guideline approved by Korean Society of Infectious Diseases and Korean Society for Nosocomial Infection Control included postpartum women (within 2 weeks post-delivery) as priority subjects [14,18]. Our study did not investigate vaccination rate postpartum, but investigated the vaccination status during pregnancy, in postpartum women.

In this study, recommendation of influenza vaccination before or during pregnancy, past experience of influenza vaccination, and the information that influenza vaccination is not dangerous during pregnancy were significant factors associated with influenza vaccination in stepwise multiple logistic regression analysis. Therefore, inadequate information and recommendation, as well as safety concern about the vaccination, before or during pregnancy, might be important barriers in women of childbearing age. 64.8% of women who were pregnant or planning a pregnancy received influenza vaccination in obstetric departments. Therefore, education of patients, guardians, and medical staffs in obstetric departments might be important.

Several studies already suggested that obstacles to influenza immunization include insufficient awareness of the disease burden and of the importance and safety of immunization, and insufficient recommendation by medical staffs [15,16,17,19,20]. Information pamphlets with correct recommendations significantly increased influenza vaccination rates in Canada [17]. In a USA study, physician education program and distribution of posters advertising the influenza vaccine to all offices offering prenatal care in local areas increased influenza vaccination rates from 19% to 31% [19]. The patient recall rates for influenza vaccination to pregnant women were also increased from 28% to 51% [19]. Because women are especially concerned of their own health and the baby's health, before pregnancy, during pregnancy and breastfeeding, it seems that education might be effective and vaccination rate can increase, if adequate information and recommendations on safety of vaccination are provided by medical staff. Prepregnancy counseling during flu season needs to include influenza vaccination. Furthermore, if Korean government incurs vaccination cost at least for pregnant women, the vaccination coverage in this high risk population will increase. Historically, national immunization programs have been successful in Korea, i.e., the fight against tuberculosis, prevention of Vertical Transmission of Hepatitis B program, measles elimination [21]. It reflects great interest of public health related to vaccination, including the awareness of preventable diseases and safety issues of vaccines, in Korea. It seems that active information communication, in digital information era, took an important role in Korea.

In conclusion, influenza vaccination rate in women of childbearing age was increased in this study and national data. More information and recommendation by healthcare workers, especially by obstetricians, including the safety of vaccination, might be critical to improving the vaccination rate in women of childbearing age.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Influenza vaccination rates in 8,518 women participants (aged between 20 and 45 years), to the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey between 2008 and 2012.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Geraldin Blanchard-Rohner (Department of Paediatrics, Children's Hospital of Geneva) for generously permitting the use of questionnaires.

References

1. Yates L, Pierce M, Stephens S, Mill AC, Spark P, Kurinczuk JJ, et al. Influenza A/H1N1v in pregnancy: an investigation of the characteristics and management of affected women and the relationship to pregnancy outcomes for mother and infant. Health Technol Assess. 2010; 14:109–182.

2. Dodds L, McNeil SA, Fell DB, Allen VM, Coombs A, Scott J, et al. Impact of influenza exposure on rates of hospital admissions and physician visits because of respiratory illness among pregnant women. CMAJ. 2007; 176:463–468.

3. Schanzer DL, Langley JM, Tam TW. Influenza-attributed hospitalization rates among pregnant women in Canada 1994-2000. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2007; 29:622–629.

4. Omer SB, Goodman D, Steinhoff MC, Rochat R, Klugman KP, Stoll BJ, et al. Maternal influenza immunization and reduced likelihood of prematurity and small for gestational age births: a retrospective cohort study. PLoS Med. 2011; 8:e1000441.

5. Poehling KA, Szilagyi PG, Staat MA, Snively BM, Payne DC, Bridges CB, et al. Impact of maternal immunization on influenza hospitalizations in infants. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011; 204:6 Suppl 1. S141–S148.

6. Wutzler P, Schmidt-Ott R, Hoyer H, Sauerbrei A. Prevalence of influenza A and B antibodies in pregnant women and their offspring. J Clin Virol. 2009; 46:161–164.

7. Harper SA, Fukuda K, Uyeki TM, Cox NJ, Bridges CB. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Prevention and control of influenza: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2004; 53(RR-6):1–40.

8. Influenza vaccines. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2005; 80:279–287.

9. World Health Organization. Pandemic (H1N1) 2009-update 112 [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization;2010. cited 2015 Jan 22. Available from: http://www.who.int/csr/don/2010_08_06/en/index.html.

10. Jamieson DJ, Honein MA, Rasmussen SA, Williams JL, Swerdlow DL, Biggerstaff MS, et al. H1N1 2009 influenza virus infection during pregnancy in the USA. Lancet. 2009; 374:451–458.

11. Creanga AA, Johnson TF, Graitcer SB, Hartman LK, Al-Samarrai T, Schwarz AG, et al. Severity of 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus infection in pregnant women. Obstet Gynecol. 2010; 115:717–726.

12. Kim MJ, Lee SY, Lee KS, Kim A, Son D, Chung MH, et al. Influenza vaccine coverage rate and related factors on pregnant women. Infect Chemother. 2009; 41:349–354.

13. Kim IS, Seo YB, Hong KW, Noh JY, Choi WS, Song JY, et al. Perception on influenza vaccination in Korean women of childbearing age. Clin Exp Vaccine Res. 2012; 1:88–94.

14. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines of vaccination for adult [Internet]. Cheongju: Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;2012. cited 2014 Apr 11. Available from: http://www.cdc.go.kr.

15. Blanchard-Rohner G, Meier S, Ryser J, Schaller D, Combescure C, Yudin MH, et al. Acceptability of maternal immunization against influenza: the critical role of obstetricians. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012; 25:1800–1809.

16. Yudin MH, Salaripour M, Sgro MD. Pregnant women's knowledge of influenza and the use and safety of the influenza vaccine during pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2009; 31:120–125.

17. Yudin MH, Salripour M, Sgro MD. Impact of patient education on knowledge of influenza and vaccine recommendations among pregnant women. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2010; 32:232–237.

18. Baek JH, Seo YB, Choi WS, Kee SY, Jeong HW, Lee HY, et al. Guideline on the prevention and control of seasonal influenza in healthcare setting. Korean J Intern Med. 2014; 29:265–280.

19. Panda B, Stiller R, Panda A. Influenza vaccination during pregnancy and factors for lacking compliance with current CDC guidelines. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2011; 24:402–406.

20. Blanchard-Rohner G, Siegrist CA. Vaccination during pregnancy to protect infants against influenza: why and why not? Vaccine. 2011; 29:7542–7550.

21. Cha SH. The history of vaccination and current vaccination policies in Korea. Clin Exp Vaccine Res. 2012; 1:3–8.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download