Abstract

Objective

To find out the factors affecting medication discontinuation in patients with overactive bladder (OAB) symptoms.

Methods

The clinical data of 125 patients with OAB symptoms who had taken antimuscarinics and behavioral therapy were retrospectively reviewed. Antimuscarinics related outcomes were evaluated by an independent observer with telephone interview. All patients were asked about duration of medication and reason of continuation or discontinuation of antimuscarinics. To determine pre-treatment factors predicting self-report discontinuation of antimuscarinics, variables of only those with P-values <0.25 on the univariate analysis were included in the Cox proportional hazard modeling.

Results

Mean follow-up was 39.6 months and the proportion of discontinuation of antimuscarinics was 60.0% (75/125). The mean duration of medication was 21.2 months in the continuation group and 3.3 months in the discontinuation group. The reasons of discontinuation of antimuscarinics were improved OAB symptoms (46.7%), tolerable OAB symptoms (33.3%), no change of OAB symptoms (1.3%), side-effects (8.0%) and no desire to take long-term medication (10.7%). The variables affecting remaining cumulative probability of antimuscarinics were age, history of anti-incontinence surgery or vaginal surgery, and having stress predominant urinary incontinence on urodynamic study.

Conclusion

The lower rate of cumulative continuation of antimuscarinics encourages us to give a more detailed counseling and education to the patients with OAB symptoms before prescription. And explorations about newer agent and non-pharmacologic treatment with good efficacy and lower side-effects are needed.

Overactive bladder (OAB) is a highly prevalent chronic disorder of urgency, with or without urge incontinence, usually with increased frequency and nocturia [1]. This condition has considerable impact on health-related quality of life in terms of daily and work activities, sleep, self-esteem, mental health, sexual function and relationships [234].

Antimuscarinic agents are considered the main stay of pharmacologic therapy of OAB treatment, and initial management of OAB is behavioral therapy along with medication [5]. Antimuscarinics alleviate patients' symptoms. Patients taking antimuscarinics have experienced a mean change in the number of incontinence episodes, number of micturitions and of urine voided per day [6]. Along with other chronic medical illness, patients need long-term treatment for relief of symptoms, but they experience variable side-effects such as dry mouth, urinary retention, constipation, blurred vision, somnolence and cognitive dysfunction [78]. Hence determining the factors associated with a tendency to discontinue ongoing treatment is necessary for predicting the effectiveness of OAB treatment. To date, only a few studies have identified the factors that affect continuation or discontinuation of antimuscarinics in OAB patients, and the data are insufficient [91011].

The aims of this study were to know the rate of discontinuation of antimusacrinics based on the out-patient urogynecological clinic setting of university hospital and to identify the pre-treatment factors affecting discontinuation of antimuscarinics in patients with OAB.

All of the OAB patients in the outpatient urogynecological clinic setting of university hospital who had been prescribed antimuscarinics 6 months ago to do this study were retrospectively identified. Medical records of these patients were reviewed and data were collected on the age, parity, menstruation history, other systemic diseases (e.g., diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and thyroid disease) surgical history (cesarean section, urinary incontinence, prolapse), and results of urodynamic studies and prescribed antimuscarinics. An independent interviewer contacted the patients by telephone to gather information. They were asked to whether they were still using antimuscarinics. Those who remained on antimuscarinics at the time of telephone survey irrespective of intervening medication free period were defined as continuation group. If they had discontinued the medication, they could choose the main reason among the precoded pool of reasons for discontinuing medication. Continuation or discontinuation of antimusacrinics information by interviewer was available on 125 patients. This study was approved by the institutional review board of Kuyng Hee University Hospital at Gangdong.

The statistical analysis was performed with SAS ver. 2.2.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Chi-square tests and independent t-tests were used to compare baseline characteristics and parameters of discontinuation and continuation group. To know the pre-treatment factors affecting discontinuation of antimuscarinics in patients with OAB, variables of only those with P-values <0.25 on the univariate analysis were included in the Cox proportional hazard modeling. The treatment discontinuation rate was evaluated with Kaplan-Meier estimate. The log rank test within Kaplan-Meier analysis was used to test for differences in the discontinuation rate for the each variable.

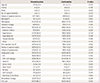

All 125 patients were divided into 2 groups according to whether they continued antimucarinics medication (continuation group) or did not continue treatment (discontinuation group) by telephone survey. Those who were defined as continuation group by telephone survey had experienced variable period of no taking medicine from 1 to 6 months in 86%. The mean follow-up duration was 39.6 months. Among the 125 patients, treatment was discontinued in 75 patients (59.7%). The median duration of taking antimuscarinics was 3.3 and 21.2 months in the discontinuation group and continuation group, respectively. The mean age of the patients was 57.5 years, and 77 (61.6%) were in a menopausal states. Sixty five patients (52.5%) had concomitant diseases. Nineteen patients (15.2%) had diabetes and 40 (32.0%) had hypertension. Thirty-three patients (26.4%) underwent surgery for urinary incontinence, and 26 (21.6%) had a history of vaginal surgery. Urodynamic study was performed in 97 patients, 86 patients had detrusor overactivity, 79 patients had uninhibited detrusor contraction with urinary leakage and 53 patients had stress incontinence (Table 1).

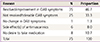

The reasons for discontinuation of antimuscarinics in the discontinuation group treatment were resolution/improvement of symptoms (46.7%), not resolved but tolerable symptoms (33.3%), persisted symptoms but no longer wanted to continue medication (10.7%), side effects of antimuscarinics (8.0%) and no effectiveness (1.3%) (Table 2).

To know the associations of pre-treatment factors with continuation of antimuscarinics, two groups between continuation and discontinuation of antimuscarinics were compared. Those who have continued antimuscarinics were significantly older (mean age, 55.3 vs. 61.1 years; P=0.01), and have a higher parity. The proportion of menopausal women was significantly higher in the continuation group (55.4% vs. 72.0%, P=0.046). Patients in the continuation group were significantly suffered from diabetes mellitus (9.5% vs. 24.0%, P=0.026). The maximum flow rate was significantly lower in the continuation group (23.9 vs. 8.9 mL/s) (Table 3).

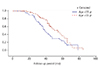

Those who were older aged, not having stress predominant urinary incontinence on urodynamic study and had not received anti-incontinence operation or surgery for vaginal prolapse had a higher adjusted cumulative probability of remaining on the antimuscarinics treatment in the Cox proportional hazards regression model (Table 4). Kaplan-Meier curves illustrate the association between age and continuation group >55 years as cut-off level (P=0.02, log rank test) (Fig. 1).

Reports from OAB pharmacotherapy had showed low persistence rates in clinical practice. Retrospective database studies of prescription records have found high discontinuation rate reaching 78% to 95% in 12-months follow-up. Age and race are identified as associated factors with medication persistence [121314]. Observational database study in which patients are monitored and self-report showed discontinuation rate of 25% in 6 month follow up. They reported that smoking, bothersome symptom with urgency and expectation about treatment efficacy and side-effects of medications is predictors of discontinuation [1115]. The range of adherence has been reported from 0.30 to 0.8. These differences are based on the length of follow up period and type of formulations [12141617].

The strengths of our study are concurrent survey of telephone interview and chart review and continuation was calculated on the cumulative probability of continuation according to time of follow up periods. Our study showed that more than half of all patients did not continue their prescriptions (60%) in the mean follow up of 40 months and most continuation group have had variable periods of no taking antimuscarinics. Relatively lower discontinuation rate in the longer length of follow up periods contrary to our expectation might in part be explained by the continuation measure with telephone interview. Self-report outcome is known to have higher persistence rate than other measures, such as prescription-fill records, biochemical testing and pill counts [1819]. The reasons of discontinuation of antimuscarinics revealed that most patients reported resolution/improvement and not resolved but tolerable symptoms. In the natural course of OAB, the bothersome symptom complex slowly progress with alternate periods of remission of variable length [20]. Unlike antihypertensive agents or anti-diabetic medication, this OAB medication does rather relieve their bothersomeness. Therefore the persistence rate of medication is influenced by heterogeneous factors including healthcare system, type of medication, follow up periods, follow up designs, etc. Also, the persistence rate should be taken into cumulative continuation according to time of follow up periods. Therefore we evaluated the factors affecting medication persistence based on the Kaplan-Meier estimate. In the univariate analysis, those who are older, menopausal women, have underlying disease of diabetes mellitus and slow peak flow rate on urodynamic study showed higher persistence rate of medication. However, in the Cox proportional hazards regression model, these risk factors were disappeared. Instead, those who were older, not having stress predominant urinary incontinence in the urodynamic study, and had not received anti-incontinence operation or surgery for vaginal prolapse showed a higher cumulative persistence of medication.

Previous studies have found cross-currents between age and persistence [1321]. Older patients who have more severe experience of OAB may derive more relieves from medication. In contrast, age and co-morbidities had a negative influence on persistence. Older patients require more medication to control OAB symptoms and other co-morbid conditions hamper persistence due to intolerable side effects or resignation. Advanced age might be another factor of persistence. In our study, the patients aged more than 55 years have adhered to OAB medication.

The finding that those who have had stress predominant urinary incontinence on urodynamic study, surgery of anti-incontinence or vagina prolapse had discontinued medication quickly suggests that it would be better for women with OAB symptoms having predominant stress incontinence or vaginal prolapse to choose corrective surgery for stress incontinence or vaginal prolapse at first before trial of medication. This is in line with previous studies. The presence of stress incontinence with OAB symptoms is described as mixed urinary incontinence. Though the consensus is lacking regarding diagnostic criteria for mixed urinary incontinence, mixed urinary incontinence is categorized into subgroup of stress predominant, urge predominant and equal components of stress and urge urinary incontinence. A meta-analysis of trials examining the effectiveness of mid-urethral slings on mixed incontinence showed that overall cure of urgency and urge urinary incontinence ranged from 30% to 85% at follow-up times of a few months up to 5 years [22]. Large prospective and retrospective trials evaluating the effectiveness of tension-free vaginal tape slings in the mixed urinary incontinence population found cure rates ranging from 52% (urge-predominant mixed urinary incontinence) to 60% (equal mixed urinary incontinence) to 80% (stress-predominant mixed urinary incontinence) [2324]. It is uncertain there is causal relationship between OAB and pelvic organ prolapse. However, research has shown that obstructive and irritative urinary symptoms increase with greater prolapse stage and these symptoms were improved after repair surgery for prolapse [25262728]. Therefore the anti-incontinence surgery should be taken into consideration in the management of OAB symptoms with stress predominant urinary incontinence or vaginal prolapse.

This study has several limitations. This retrospective study is associated with potential bias, including errors in encoding data of existing chart and recall bias of patients' memories. The study population is not large and confined the women visiting urogynecologic clinic of hospital. Also there is also lack of information on type and dose of antimuscarinics, other adjunctive modalities of bladder training, behavioral therapy or pelvic floor exercise. The well designed prospective studies are needed to know the factors affecting OAB medication persistence rate in the right of these argued elements. And explorations about newer agent and non-pharmacologic treatment with good efficacy and lower side-effects are needed.

In conclusion, this study identified those patients more likely to continue medication for OAB symptoms. Such would be useful information for pre-treatment consultations and for improving treatment compliance in patients with OAB symptoms

Figures and Tables

Table 3

The association of pre-treatment factors with two groups of antimuscarinics in the treatment of overactive bladder symptoms

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation or proportion (%).

BMI, body mass index; UI, urinary incontinence; DO, detrusor overactivity; UDC, uninhibitied detrusor contractions; Qmax, maximum flow rate; Qave, average flow rate; RV, residual volume; VLPP, Valsalva leak point pressure; PdetQmax, detrusor pressure at maximum flow rate.

References

1. Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, Griffiths D, Rosier P, Ulmsten U, et al. The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: report from the Standardisation Sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn. 2002; 21:167–178.

2. Coyne KS, Sexton CC, Irwin DE, Kopp ZS, Kelleher CJ, Milsom I. The impact of overactive bladder, incontinence and other lower urinary tract symptoms on quality of life, work productivity, sexuality and emotional well-being in men and women: results from the EPIC study. BJU Int. 2008; 101:1388–1395.

3. Kannan H, Radican L, Turpin RS, Bolge SC. Burden of illness associated with lower urinary tract symptoms including overactive bladder/urinary incontinence. Urology. 2009; 74:34–38.

4. Sexton CC, Coyne KS, Vats V, Kopp ZS, Irwin DE, Wagner TH. Impact of overactive bladder on work productivity in the United States: results from EpiLUTS. Am J Manag Care. 2009; 15:4 Suppl. S98–S107.

5. Natalin R, Lorenzetti F, Dambros M. Management of OAB in those over age 65. Curr Urol Rep. 2013; 14:379–385.

6. Chapple CR, Khullar V, Gabriel Z, Muston D, Bitoun CE, Weinstein D. The effects of antimuscarinic treatments in overactive bladder: an update of a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Urol. 2008; 54:543–562.

7. Wagg AS. Antimuscarinic treatment in overactive bladder: special considerations in elderly patients. Drugs Aging. 2012; 29:539–548.

8. Mauseth SA, Skurtveit S, Spigset O. Adherence, persistence and switch rates for anticholinergic drugs used for overactive bladder in women: data from the Norwegian Prescription Database. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2013; 92:1208–1215.

9. Michel MC, Schneider T, Krege S, Goepel M. Does gender or age affect the efficacy and safety of tolterodine? J Urol. 2002; 168:1027–1031.

10. Richter HE, Burgio KL, Chai TC, Kraus SR, Xu Y, Nyberg L, et al. Predictors of outcomes in the treatment of urge urinary incontinence in women. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009; 20:489–497.

11. Brubaker L, Fanning K, Goldberg EL, Benner JS, Trocio JN, Bavendam T, et al. Predictors of discontinuing overactive bladder medications. BJU Int. 2010; 105:1283–1290.

12. Yu YF, Nichol MB, Yu AP, Ahn J. Persistence and adherence of medications for chronic overactive bladder/urinary incontinence in the california Medicaid program. Value Health. 2005; 8:495–505.

13. Shaya FT, Blume S, Gu A, Zyczynski T, Jumadilova Z. Persistence with overactive bladder pharmacotherapy in a Medicaid population. Am J Manag Care. 2005; 11:4 Suppl. S121–S129.

14. D'Souza AO, Smith MJ, Miller LA, Doyle J, Ariely R. Persistence, adherence, and switch rates among extended-release and immediate-release overactive bladder medications in a regional managed care plan. J Manag Care Pharm. 2008; 14:291–301.

15. Benner JS, Nichol MB, Rovner ES, Jumadilova Z, Alvir J, Hussein M, et al. Patient-reported reasons for discontinuing overactive bladder medication. BJU Int. 2010; 105:1276–1282.

16. Lawrence M, Guay DR, Benson SR, Anderson MJ. Immediate-release oxybutynin versus tolterodine in detrusor overactivity: a population analysis. Pharmacotherapy. 2000; 20:470–475.

17. Balkrishnan R, Bhosle MJ, Camacho FT, Anderson RT. Predictors of medication adherence and associated health care costs in an older population with overactive bladder syndrome: a longitudinal cohort study. J Urol. 2006; 175(3 Pt 1):1067–1071.

18. Krueger KP, Berger BA, Felkey B. Medication adherence and persistence: a comprehensive review. Adv Ther. 2005; 22:313–356.

19. Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med. 2005; 353:487–497.

20. Malmsten UG, Molander U, Peeker R, Irwin DE, Milsom I. Urinary incontinence, overactive bladder, and other lower urinary tract symptoms: a longitudinal population-based survey in men aged 45-103 years. Eur Urol. 2010; 58:149–156.

21. Basra RK, Wagg A, Chapple C, Cardozo L, Castro-Diaz D, Pons ME, et al. A review of adherence to drug therapy in patients with overactive bladder. BJU Int. 2008; 102:774–779.

22. Jain P, Jirschele K, Botros SM, Latthe PM. Effectiveness of midurethral slings in mixed urinary incontinence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Urogynecol J. 2011; 22:923–932.

23. Kulseng-Hanssen S, Husby H, Schiotz HA. Follow-up of TVT operations in 1,113 women with mixed urinary incontinence at 7 and 38 months. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008; 19:391–396.

24. Kulseng-Hanssen S, Husby H, Schiotz HA. The tension free vaginal tape operation for women with mixed incontinence: do preoperative variables predict the outcome? Neurourol Urodyn. 2007; 26:115–121.

25. Bradley CS, Nygaard IE. Vaginal wall descensus and pelvic floor symptoms in older women. Obstet Gynecol. 2005; 106:759–766.

26. Digesu GA, Salvatore S, Chaliha C, Athanasiou S, Milani R, Khullar V. Do overactive bladder symptoms improve after repair of anterior vaginal wall prolapse? Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007; 18:1439–1443.

27. de Boer TA, Kluivers KB, Withagen MI, Milani AL, Vierhout ME. Predictive factors for overactive bladder symptoms after pelvic organ prolapse surgery. Int Urogynecol J. 2010; 21:1143–1149.

28. Miranne JM, Lopes V, Carberry CL, Sung VW. The effect of pelvic organ prolapse severity on improvement in overactive bladder symptoms after pelvic reconstructive surgery. Int Urogynecol J. 2013; 24:1303–1308.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download