Abstract

Objective

To determine if neurofilament (NF) is expressed in the endometrium and the lesions of myomas and adenomyosis, and to determine their correlation.

Methods

Histologic sections were prepared from hysterectomies performed on women with adenomyosis (n=21), uterine myoma (n=31), and carcinoma in situ of the uterine cervix. Full-thickness uterine paraffin blocks, which included the endometrium and myometrium histologic sections, were stained immunohistochemically using the antibodies for monoclonal mouse antihuman NF protein.

Results

NF-positive cells were found in the endometrium and myometrium in 11 women with myoma and in 7 with adenomyosis, but not in patients with carcinoma in situ of uterine cervix, although the difference was statistically not significant. There was no significant difference between the existence of NF-positive cells and menstrual pain or phases. The NF-positive nerve fibers were in direct contact with the lesions in nine cases (29.0%) of myoma and in five cases (23.8%) of adenomyosis. It was analyzed if there was a statistical significance between the existence of NF positive cells in the endometrium and the expression of NF-positive cells in the uterine myoma/adenomyosis lesions. When NF-positive cell were detected in the myoma lesions, the incidence of NF-positive nerve cells in the eutopic endometrium was significantly high. When NF-positive cell were detected in the basal layer, the incidence of NF-positive nerve cells in the myoma lesions and adenomyosis lesions was significantly high.

Anatomically nerves are distributed through the myometrium, along neurovascular bundles, from two intrinsic plexi: a subserosal plexus and a plexus at the endometrial-myometrial junction [1]. Recently, there has been increasing evidence of the innervation of the endometrium by small nerve fibers in women with endometriosis, but not in women without endometriosis. Tokushige et al. [2] reported that in women with laparoscopy-confirmed endometriosis, small nerve fibers were stained positive for protein gene product (PGP) 9.5 in the functional layer of the eutopic endometrium, but PGP 9.5 was not detected in the endometrium of women without endometriosis. Nerve fibers also were detected in endometriotic plaques, abdominal adhesions, and the endometrium and myometrium [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. Neurofilament (NF) is expressed in the axon and often, in myelinated fibers. Therefore, NF serves as a specific marker of nerve fibers, and NF monoclonal antibodies are used to detect the existence of nerve fibers in histology. Endometriosis-related adhesions contained NF-positive nerve fibers [10], and nerve fibers that were stained positive for PGP 9.5, NF, calcitonin gene-related peptide, substance P, and vasoactive intestinal polypeptide were present in the endometrium and the myometrium of women with painful endometriosis [2,3].

Adenomyosis is a disease that involves myometrial invasion by endometrial glands and stroma, and is presented as localized or diffuse lesions. Dysmenorrhea is one of its major clinical symptoms, and is believed to be positively correlated with adenomyotic foci [11]. Adenomyosis and endometriosis are believed to be controlled by steroid hormones. These nerve fibers were not detected in adenomyotic lesions, however, and did not exist at the endometrial-myometrial interface of the uterus with adenomyosis [12].

Uterine myomas are monoclonal, benign, and smooth muscle tumors of the uterine myometrium, and are the most common causes of gynecologic surgery in women. A series of clinic-based studies have shown that approximately 34% of women with uterine myoma have pelvic pain and/or dysmenorrhea symptoms [13,14]. Zhang et al. [15] reported that PGP 9.5-positive nerve fibers were observed in the functional layer of the endometrium of women with painful adenomyosis and uterine fibroids, but not in that of women with adenomyosis and uterine fibroids but without pain.

In this study, NF-positive nerves in the lesions of women with adenomyosis and uterine myomas were examined. Then it was evaluated if NF is expressed in myoma and adenomyosis lesions, as in peritoneal endometriotic lesions, and it was analyzed if this expression is related to pain and the expression of NF in the endometrium.

Full-thickness uterine paraffin blocks, which included the endometrium and the myometrium, were selected retrospective from 52 women with adenomyosis (n=21) and uterine myoma (n=31) who were underwent hysterectomy from January 2012 to December 2012 at university based hospital. In addition, control specimens were obtained from 13 women who had undergone hysterectomy for carcinoma in situ of the uterine cervix without endometriosis. The study protocol for research purposes was approved by the institutional review board.

To determine if other diseases might be included in the diagnosis of adenomyosis and uterine myoma, a gynecologic histopathologist re-examined the confirmed previous diagnosis. Medical and pain histories of all subjects were obtained from medical records. We excluded cases with the medical histories (endometriosis and pelvic inflammatory disease) and treatments (Gonadotropin analog, oral contraceptives, and steroid). All the samples of the endometrium were examined to determine the phases of the menstrual cycle. Of the 31 women with uterine myoma, 13 were in the proliferative phase and 18 were in the secretory phase. Of the 21 women with adenomyosis, six were in the proliferative phase and 15 were in the secretory phase.

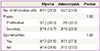

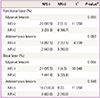

The medical and pain histories of all the subjects were obtained from their medical records. In the women with adenomyosis, 11 complained of dysmenorrheal and/or pelvic pain, and 10 had no pain symptoms. In the women with uterine myoma, 17 complained of dysmenorrheal and/or pelvic pain, and 14 had no pain symptoms. In the control group, three complained of dysmenorrheal and/or pelvic pain, and 10 had no pain symptoms (Table 1).

The tissue samples were immunostained according to the standard protocol. Sections from paraffin block were 4 µm, deparaffinized, and rehydrated with xylene and graded alcohols. Microwave epitope retrieval was performed. BenchMark Autostainer (Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, AZ, USA) was used for immunohistochemical staining. The following monoclonal mouse antibodies were used: anti-NF (diluted at 1:200; Dako, Carpinteria, CA, USA). As a positive control for NF, a normal skin tissue was used. Positive staining was defined as the detection of NF in the cytoplasm. Examples of positive stains are illustrated in Fig. 1. The results described the percentage of NF-positive nerve fibers in the endometrium.

The morphology of the NF-positive cells around the endometrial glands was similar to that of the stromal cells, whereas the NF-positive cells around the endometrial epithelial surfaces were elongated (Fig. 1). These NF-positive cells were also observed among the perivascular cells, as in the neurovascular bundles of the basalis and the myometrium.

In the control group, NF-positive cells were not observed in the functional layer of the endometrium, but were seen in the functional layer of the endometrium (Table 2) in 25.8% of the subjects with myoma (8/31) and in 23.8% of the subjects with adenomyosis (5/21). The differences were statistically insignificant. NF-positive cells were not detected in the basalis of the endometrium in the control group, but were seen in the basalis of the endometrium of 19.4% (6/31) of the subjects with myoma and of 9.5% (2/21) of the subjects with adenomyosis. The differences were also statistically insignificant. The expression of NF-positive cells according to the menstrual phase was no statistically difference. And there was no significant between the existence of NF-positive cells in the functional layer or in the basalis and the pain reported by the patients (Table 3).

In the myometrium, NF-positive cells were not detected in the control group, but were seen in the myometrium of 6.5% (2/31) of the subjects with myoma and of 4.8% (1/21) of the subjects with adenomyosis. The differences were statistically insignificant.

The NF-positive nerve fibers were in direct contact with the lesions in nine cases (29.0%) of myoma and in five cases (23.8%) of adenomyosis (Table 2). The nerve fibers were occasionally detected in the stromal cells or in adjacent connective tissues. It was analyzed if there was a significant difference between the existence of NF positive cells in the endometrium and the expression of NF-positive cells in the uterine myoma/adenomyosis lesions. When NF-positive cell were detected in the myoma lesions, the incidence of NF-positive nerve cells in the eutopic endometrium was significantly high (Table 4). When NF-positive cell were detected in the basal layer, the incidence of NF-positive nerve cells in the myoma lesions and adenomyosis lesions was significantly high (Table 4).

In this study, NF-positive cells were not observed in the control group but were detected in the endometrium and the myometrium of women with myoma and adenomyosis, although the difference between the groups was statistically insignificant. No correlation was found between the existence of NF-positive cells and menstrual pain or phases. Zhang et al. [16] reported, however, that PGP 9.5-positive nerve fibers were present only in the functional layer of the endometrium of women with pain symptoms. NF-positive nerve fibers were also detected in the basal layer of the endometrium and in the myometrium of women with adenomyosis and uterine fibroids, although their incidence was statistically insignificant. They suggested that PGP 9.5-positive nerve fibers but not NF-positive nerve fibers in the endometrium and the myometrium play a role in pain generation in women with adenomyosis and uterine fibroids. In a study of endometriosis and pain, however, Mechsner et al. [7] reported that nerve cells in peritoneal endometriotic lesions were stained positive for NF and substance P, a marker of sensory nerve fibers.

NF plays a role in the formation of a structural framework and in the control of the shapes and sizes of nerves. Most NFs are expressed in the axon and often, in myelinated fibers. Therefore, NF serves as a specific marker of nerve fibers, and NF monoclonal antibodies are used to detect the existence of nerve fibers in histology. NF is seemingly not well-represented, however, in all populations of nerves or in all neuronal regions [17,18].

In contrast, the PGP 9.5 was reported as a general cytoplasmic marker that is expressed in all types of efferent and afferent nerve fibers [19], although its function is unknown. PGP 9.5, a cytoplasmic protein in neurons and neuro-endocrine cells, is expressed in both efferent and afferent nerves, and thus, serves as a general cytoplasmic marker. PGP 9.5 neurons were suggested as sensory unmyelinated C nerve fibers that are related to pain such as by transmitting dull, throbbing, and diffuse pain [20]. NF stains indicated the occurrence of myelinated Ad fibers, which send quick localized pain signals toward the brain and the spinal cord, in the deep endometrial basal layer of confirmed endometriosis patients. Similar findings were not detected in women without endometriosis [21].

In contrast to the report of Zhang et al. [16], the existence of NF-positive cells in the functional layer of the endometrium of 23.5% of the patients with myoma and of 23.8% of the patients with adenomyosis was observed in this study, although the difference between the groups was statistically insignificant. Therefore, efforts to understand the characteristics and the function of the nerves defined by specific staining methods should continue.

The mechanism of dysmenorrheal and pelvic pain in women with uterine myoma and adenomyosis is not well-understood. Prostaglandins play an important role in pain generation, and have been suggested as activating or sensitizing sensory C fiber endings by interacting with cell-surface receptors in the endometrium of women with endometriosis [22]. Pain mediators react with nociceptors to induce pain [23]. Mechsner et al. [7] suggested that NF-positive nerve fibers in peritoneal endometriotic lesions are pain-conducing nerve fibers and are important causes of pain related to peritoneal endometriosis. It was also suggested that the nerve fibers in myoma and adenomyosis could play an important role in disease-related pain. Endometriosis, myoma, and adenomyosis are estrogen-dependent diseases wherein estrogen may provide a trophic support to nerve fibers by regulating the production of neurotropins and other molecules that are associated with nerve fiber growth in the endometirum and the myometrium of women with these diseases.

Many researchers have studied the roles of the nerves in the endometrium. Tokushige et al. [2] reported from their study using immunostaining methods that the nerves in the functional layer and the basalis of the endometrium are sensory C fibers and adrenergic fibers. The functional layer of the endometrium showed mostly sensory unmyelinated C nerve fibers that are responsible for transmitting dull, throbbing, and diffuse pain. They suggested that these nerves play a role in the generation of pain. Inflammatory mediators, which are released from the endometrium, can activate or sensitize sensory C fiber endings to evoke neurogenic inflammation [24,25]. Adrenergic fiber endings can release prostaglandin E2, prostacycline, and norepinephrine, which can sensitize sensory C [26,27].

In summary, NF-positive cells were observed in the endometrium and the myometrium of women with myoma and adenomyosis, although they could not be statistically verified. There was no significant between the existence of NF-positive cells in the functional layer or in the basalis and the pain/phases. However, when NF-positive cell were detected in the myoma lesions, the incidence of NF-positive nerve cells in the eutopic endometrium was significantly high. It was assumed that NF-positive cells in the endometrium and the myoma and adenomyosis lesions might play a role in pathogenesis. Therefore, more studies may be needed on the mechanisms of nerve fiber growth in estrogen-dependent diseases.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Neurofilamen (NF)-positive cells in the functional and basal layers of the endometrium and in the myometrium of women with uterine myoma and adenomyosis. (A) NF as a positive control (×100). (B) Endometrium in the functional layer of a woman with uterine myoma that was stained for NF (×40). (C) Uterine myomas stained via H&E staining (×100). (D) After the NF immunostaining, NF-immunostained nerve fibers in the of myoma lesion in some cases (×100). (E) Endometrium in the functional layer of a woman with uterine adenomyosis for NF (×40). (F) NF-immunostained nerve fibers in the adenomyosis lesion in some cases (×40). (G) Stromal cells of the adenomyosis lesions that were immunostained via H&E staining (×200). (H) After the NF immunostaining, NF-immunostained nerve fibers in the adenomyosis lesion in some cases (×200).

Table 2

Distribution of NF-positive cells in women who showed positive NF stain in at least one location (0 women with CIS [controls], 11 with myoma, and 7 with adenomyosis)

Values are presented as n (%).

NF, neurofilament; CIS, carcinoma in situ; -, NF staining negative; +, NF staining positive.

a)Fisher's exact test P-value is 0.082 between control and myoma group; b)Fisher's exact test P-value is 0.163 between control and myoma group; c)Fisher's exact test P-value is 0.523 between control and myoma group; d)Fisher's exact test P-value is 0.132 between control and adenomyosis group; e)Fisher's exact test P-value is 1.000 between control and adenomyosis group; f)Fisher's exact test P-value is 1.000 between control and adenomyosis group.

References

1. Krantz KE. Innervation of the human uterus. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1959; 75:770–784.

2. Tokushige N, Markham R, Russell P, Fraser IS. High density of small nerve fibres in the functional layer of the endometrium in women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2006; 21:782–787.

3. Atwal G, du Plessis D, Armstrong G, Slade R, Quinn M. Uterine innervation after hysterectomy for chronic pelvic pain with, and without, endometriosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005; 193:1650–1655.

4. Anaf V, Simon P, El Nakadi I, Fayt I, Simonart T, Buxant F, et al. Hyperalgesia, nerve infiltration and nerve growth factor expression in deep adenomyotic nodules, peritoneal and ovarian endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2002; 17:1895–1900.

5. Anaf V, Chapron C, El Nakadi I, De Moor V, Simonart T, Noel JC. Pain, mast cells, and nerves in peritoneal, ovarian, and deep infiltrating endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2006; 86:1336–1343.

6. Anaf V, Simon P, El Nakadi I, Fayt I, Buxant F, Simonart T, et al. Relationship between endometriotic foci and nerves in rectovaginal endometriotic nodules. Hum Reprod. 2000; 15:1744–1750.

7. Mechsner S, Schwarz J, Thode J, Loddenkemper C, Salomon DS, Ebert AD. Growth-associated protein 43-positive sensory nerve fibers accompanied by immature vessels are located in or near peritoneal endometriotic lesions. Fertil Steril. 2007; 88:581–587.

8. Sulaiman H, Gabella G, Davis C, Mutsaers SE, Boulos P, Laurent GJ, et al. Presence and distribution of sensory nerve fibers in human peritoneal adhesions. Ann Surg. 2001; 234:256–261.

9. Tamburro S, Canis M, Albuisson E, Dechelotte P, Darcha C, Mage G. Expression of transforming growth factor beta1 in nerve fibers is related to dysmenorrhea and laparoscopic appearance of endometriotic implants. Fertil Steril. 2003; 80:1131–1136.

10. Tulandi T, Chen MF, Al-Took S, Watkin K. A study of nerve fibers and histopathology of postsurgical, postinfectious, and endometriosis-related adhesions. Obstet Gynecol. 1998; 92:766–768.

11. Kissler S, Zangos S, Kohl J, Wiegratz I, Rody A, Gatje R, et al. Duration of dysmenorrhoea and extent of adenomyosis visualised by magnetic resonance imaging. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2008; 137:204–209.

12. Quinn M. Uterine innervation in adenomyosis. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2007; 27:287–291.

13. Bukulmez O, Doody KJ. Clinical features of myomas. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2006; 33:69–84.

14. Lippman SA, Warner M, Samuels S, Olive D, Vercellini P, Eskenazi B. Uterine fibroids and gynecologic pain symptoms in a population-based study. Fertil Steril. 2003; 80:1488–1494.

15. Zhang X, Lu B, Huang X, Xu H, Zhou C, Lin J. Endometrial nerve fibers in women with endometriosis, adenomyosis, and uterine fibroids. Fertil Steril. 2009; 92:1799–1801.

16. Zhang X, Lu B, Huang X, Xu H, Zhou C, Lin J. Innervation of endometrium and myometrium in women with painful adenomyosis and uterine fibroids. Fertil Steril. 2010; 94:730–737.

17. Bishop AE, Carlei F, Lee V, Trojanowski J, Marangos PJ, Dahl D, et al. Combined immunostaining of neurofilaments, neuron specific enolase, GFAP and S-100: a possible means for assessing the morphological and functional status of the enteric nervous system. Histochemistry. 1985; 82:93–97.

18. Hacker GW, Polak JM, Springall DR, Ballesta J, Cadieux A, Gu J, et al. Antibodies to neurofilament protein and other brain proteins reveal the innervation of peripheral organs. Histochemistry. 1985; 82:581–593.

19. Gulbenkian S, Wharton J, Polak JM. The visualisation of cardiovascular innervation in the guinea pig using an antiserum to protein gene product 9.5 (PGP 9.5). J Auton Nerv Syst. 1987; 18:235–247.

20. Tokushige N, Markham R, Russell P, Fraser IS. Nerve fibres in peritoneal endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2006; 21:3001–3007.

21. Medina MG, Lebovic DI. Endometriosis-associated nerve fibers and pain. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2009; 88:968–975.

22. Harel Z. Dysmenorrhea in adolescents and young adults: from pathophysiology to pharmacological treatments and management strategies. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2008; 9:2661–2672.

23. Apfel SC. Neurotrophic factors and pain. Clin J Pain. 2000; 16:2 Suppl. S7–S11.

24. Mantyh PW. Neurobiology of substance P and the NK1 receptor. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002; 63:Suppl 11. 6–10.

25. Schaible HG, Ebersberger A, Von Banchet GS. Mechanisms of pain in arthritis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002; 966:343–354.

26. Gonzales R, Goldyne ME, Taiwo YO, Levine JD. Production of hyperalgesic prostaglandins by sympathetic postganglionic neurons. J Neurochem. 1989; 53:1595–1598.

27. Banik RK, Sato J, Yajima H, Mizumura K. Differences between the Lewis and Sprague-Dawley rats in chronic inflammation induced norepinephrine sensitivity of cutaneous C-fiber nociceptors. Neurosci Lett. 2001; 299:21–24.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download