Abstract

Postpartum genital tract adhesions are unusual, and their cause has not been evaluated. However, severe dystocia and numerous pelvic examinations have been suggested as possible causes. Here, we report a case of vaginal adhesions following a difficult labor that presented as dyspareunia for 5 months. Pelvic examination and ultrasonography revealed a transverse vaginal septum that obstructed the vaginal cavity, and fluid collection proximal to this septum. The patient was successfully treated with surgical resection and administration of antibiotics.

Vaginal adhesions usually refer to adhesion of the labia minora in prepubertal girls. These labial adhesions are common in young girls and can also occur in elderly women. In contrast, labial adhesions or an actual adhesion of the vaginal cavity in reproductive aged women are known to be rare [1]. Several cases of labial adhesions in postpartum women have been reported [1-4] but adhesion of the vaginal cavity in humans has not been reported to the best of our knowledge. Also, the cause of postpartum vaginal adhesions is not fully understood. Here, we report a case of an adhesion of the vaginal cavity by the vaginal septum in a postpartum woman with a history of difficult labor, along with a review of the literature.

A 32-year-old woman (gravida 4, para 2) visited our institution due to dyspareunia lasting for 5 months after her second delivery. Seven years before her visit, she delivered her first baby by Cesarean section due to progression failure. However, she succeeded in vaginal birth after a Cesarean delivery (VBAC) for her second delivery at another institution. She reported that during her second labor, she underwent numerous pelvic examinations because her labor did not progress smoothly. Finally, she underwent a vaginal delivery of a female infant weighing 3,580 g without applying vacuum or forceps. She did not visit at her scheduled postpartum examination after her second delivery, therefore, her perineal area was not explored after her vaginal birth.

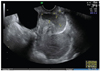

After her second birth, she experienced dyspareunia and her husband could not resume his sexual activity due to inability to achieve full penile insertion. Also, she reported the immediate leakage of semen after intercourse. In addition, her menstruation did not resume, but she attributed this phenomenon to breastfeeding. There was no abnormal finding in her vital signs and laboratory tests. However, it was hard to insert the speculum fully into her vagina because of her blind vagina canal. Also, her cervix could not be visualized by speculum examination. As a result of a thick transverse vaginal septum blocking her vaginal cavity, we could insert a speculum only 2 to 3 cm into her vagina (Fig. 1A). Transvaginal ultrasonography (Voluson 730 Expert, GE Medical Systems, Zipf, Austria) showed a transverse vaginal septum measuring 0.94 cm thick and a fluid-filled cavity beyond it (Fig. 1B). Vaginal adhesion was diagnosed and she was admitted for treatment of this rare condition.

After hospitalization, prophylactic intravenous antibiotics (3rd-generation cephalosporin with metronidazole) were administered first. After the day of admission, the fluid in the obstructed vaginal cavity was aspirated and examined. This fluid was turbid and had a foul odor but no bacteria were found upon culture examination. With this aspiration, we excised the vaginal septum and sutured the remained edge of this septum to the vaginal wall using 2-0 Vicryl (Ethicon Inc., Somerville, NJ, USA) (Fig. 2). After the operation, we inserted Vaseline gauze into the vaginal cavity to prevent re-adhesion and hemorrhage. This packed gauze was maintained during the whole hospitalization period and changed every day. Antibiotics were administered intravenously for 5 days and she was discharged on day 5 after the operation. Three months following surgery, she noticed an improvement in her dyspareunia and resumed sexual activity. Pelvic examination revealed a well-maintained vaginal cavity.

True vaginal adhesion is a rare condition, and we found only one case of vaginal adhesion complicated with pyometra in a miniature horse in a Medline search using the terms "vaginal adhesion" in combination with "postpartum" or "postnatal" [5]. Also, labial adhesions usually develop in prepubertal girls or postmenopausal women due to irritation or a hypoestrogenic state [1]. That is, vaginal adhesions including labial adhesions are rare in women of reproductive age. Several postpartum labial adhesions have been reported [1-4]. Unlike labial adhesions in young girls or postmenopausal women, postpartum labial adhesions do not respond to topical estrogen cream, therefore, surgical treatment is usually warranted [2]. Surgical excision is usually possible under local anesthesia but general anesthesia may be required for massive adhesions [2]. Our case was successfully treated by surgical treatment under general anesthesia. Rarely, in postpartum labial adhesions refractory to surgical treatment, amniotic membrane grafting can be used [6].

The causes of postpartum genital tract adhesions have not been completely evaluated. Previous reports showed that genital tract trauma such as large vulvar edema, or vaginal or labial laceration is associated with postpartum labial adhesions [2]. In our case, the patient reported dystocia and numerous pelvic examinations. We assumed that her difficult labor, even though it was not certain because it was not at our institution, resulted in numerous pelvic examinations by obstetricians and increased vaginal wall laceration. During the healing process after this trauma, fibrotic tissues formed a septum in her vaginal cavity, causing dyspareunia and sexual disability. We did not see this case from the start, therefore, we were unable to ascertain whether she had a septum in her vagina before. However, we guessed that she did not have a septum because she could undergo VBAC. Thus, we thought that the vaginal adhesion might have been due to fibrotic tissues forming a septum in her vaginal cavity after VBAC, but we could not rule out the possibility of re-adhesion after delivery. Another possible cause of postpartum labial adhesions is breastfeeding [7]. Breastfeeding increases the level of prolactin, and it can cause a hypoestrogenic state associated with labial adhesions. However, there is a concern that a hypoestrogenic state may not be associated with postpartum labial adhesions because most postpartum labial adhesions do not respond to estrogen therapy [2].

Strangely, our case presented as actual obstruction of the vaginal cavity, and not simple labial adhesions. We assumed that it would be hard to find the vaginal adhesions without careful examination; unlike postpartum labial adhesions that are easily found at scheduled postpartum visits. To the best of our knowledge, there have not been reports of vaginal adhesions in humans, and the vaginal adhesions in a miniature horse were confirmed after autopsy [5]. This implies that scheduled postpartum examination should be especially emphasized in women with difficult labor. In addition, if women complain of dyspareunia or sexual disability after delivery, more careful pelvic examination is recommended.

Standard care of the perineum after vaginal delivery has not been established and practices vary widely among obstetricians [8]. However, the evidence available recommends paying particular attention to perineal hygiene, cryotherapy, foot elevation, and regular pelvic floor exercises [9]. In addition, women should be encouraged to undertake labial and cyclic cleansing of the perineum with a peri-bottle or sitz bath [2]. We might also recommend that obstetricians avoid multiple pelvic examinations and genital tract trauma in an attempt to prevent postpartum genital tract adhesions.

In conclusion, we hope that our case will increase concern about postpartum genital tract adhesions and postpartum perineal care. In addition, further research should attempt to establish the best method of prevention and management of this rare postpartum complication.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Sharma B, Arora R, Preston J. Postpartum labial adhesions following normal vaginal delivery. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2005; 25:215.

2. Seehusen DA, Earwood JS. Postpartum labial adhesions. J Am Board Fam Med. 2007; 20:408–410.

3. Shaver D, Ling F, Muram D. Labial adhesions in a postpartum patient. Obstet Gynecol. 1986; 68:24S–25S.

4. Arkin AE, Chern-Hughes B. Case report: labial fusion postpartum and clinical management of labial lacerations. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2002; 47:290–292.

5. Cozens ER. Pyometra and complete vaginal adhesion in a miniature horse. Can Vet J. 2009; 50:971–972.

6. Lin YH, Hwang JL, Huang LW, Chou CT. Amniotic membrane grafting to treat refractory labial adhesions postpartum: a case report. J Reprod Med. 2002; 47:235–237.

7. Steele EK, Lowry DS. Labial adhesions following normal delivery. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2002; 22:555.

8. Rhode MA, Barger MK. Perineal care. Then and now. J Nurse Midwifery. 1990; 35:220–230.

9. Chiarelli P, Cockburn J. Postpartum perineal management and best practice. Aust Coll Midwives Inc J. 1999; 12:14–18.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download