Abstract

Uterine arteriovenous malformation (AVM) is a rare entity in gynecology with fewer than 100 cases reported in the literature. Due to abnormal connection between arteries and veins without an intervening capillary system, recurrent and profuse vaginal bleeding is the most common symptom which can be potentially life-threatening. Uterine AVM can be either congenital or acquired. Acquired AVM is reported as a consequence of previous uterine trauma such as curettage procedures, caesarean section or pelvic surgery. It is also associated with infection, retained product of conception, gestational trophoblastic disease, malignancy and exposure to diethlystilboestrol. We herein report a case of acquired uterine AVM located on the right lateral wall after intrauterine instrumentation for laparoscopic left salpingectomy due to left tubal pregnancy. The patient was successfully treated with embolization.

Uterine arteriovenous malformation (AVM) is rare but potentially life-threatening. The main symptom of uterine AVM is recurrent and profuse vaginal bleeding. The cause can be congenital or acquired. Acquired AVM is reported as a consequence of previous uterine trauma such as curettage procedures, caesarean section or pelvic surgery. It is also associated with infection, retained product of conception, gestational trophoblastic disease, malignancy and exposure to diethlystilboestrol. The diagnosis is made by imaging study including grayscale and doppler sonography, computerized tomography (CT) scan, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and angiography. We experienced a case of acquired uterine AVM located on the right later wall after intrauterine instrumentation for laparoscopic left salpingectomy due to left tubal pregnancy. The imaging study including sonography and CT scan was performed for work up and under the impression of AVM, angiography along with right uterine artery embolization was performed. The patient was successfully treated and discharged without complications.

A 27-year-old woman gravida 3, para 0 visited our emergency department with aggravating left lower quadrant abdominal pain and vaginal spotting. She had obstetric history of three artificial abortion, with last abortion experience three years ago. Urine beta human chorionic gonadotropin (beta hCG) was positive. Based on her last menstrual period, she was at 7+3/7 weeks of gestation. Upon arrival, she was hemodynamically stable with a hemoglobin (Hb) level of 12.6 g/dL. Physical examination showed direct and rebound tenderness in the left lower quadrant of abdomen. Transvaginal ultrasonography (US) showed about 1.6×1.4-cm-sized heterogenous echogenic mass located next to normal left ovary with no gestational sac seen within the uterus, and no other abnormal findings within the uterus was found (Fig. 1). Also small amount of fluid collection in posterior cul-du-sac was observed indicating possible hemoperitoneum with no other abnormal findings in the uterus or right adnexa. We performed laparoscopic left salpingectomy under the impression of ruptured left tubal pregnancy. The uterine manipulator, known as ZUMI, was used during surgery and no other additional procedure, such as curettage was performed. The pathology confirmed left tubal pregnancy. Also, quantitative beta hCG level decreased from 1,761 to 170.6 mIU/mL on discharge. She was discharged three days after operation without any complications.

Four days after the discharge, she revisited our emergency department. This time she admitted after experiencing syncope due to massive vaginal bleeding for two days. Upon arrival, she was alert but vital signs were unstable; blood pressure was 76/48 mmHg with pulse rate of 69 beats/min. Initial Hb level was 8.4 g/dL and one hour after Hb level dropped to 5.6 g/dL. Immediate resuscitation with massive intravenous fluid therapy and packed red blood cell transfusion was preformed. The beta hCG was 23.8 mIU/mL.

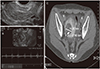

Transvaginal US showed about 0.3-cm-sized bud like tubular lesion surrounded by anechogenic cystic space in the right lateral wall of myometrium with normal endometrium. No other abnormal findings were seen. The pulse rate of 71 beats/min was checked in the lesion. For further evaluation CT scan was performed which showed about 1.4-cm-sized contrast-opacified structure surrounded by 3.7-cm-sized low density lesion (Fig. 1). A diagnosis of uterine AVM was considered and an angiogram for confirmation was required.

The uterine artery angiogram confirmed the presence of an AVM in the right lateral wall region which originated from right uterine artery (Fig. 2). The lesion was successfully embolized with a mixture of glue and lipidol (1:2) via a microcatheter placed at the feeding artery and nidus. The embolization of the drainage veins were performed with 150-250 microns polyvinyl alcohol particles. The right uterine artery appeared hypertrophy and hypervascular staining was observed, thus additional embolization was peformed with gelfoam. The post-embolization angiogram showed complete embolization of the AVM (Fig. 2). No complicaions were encountered and she recovered uneventfully. The patient's vaginal bleeding decreased after embolization and there were no further episodes of abnormal profuse vaginal bleeding. Two days after embolization, before the patient was discharged, follow up beta hCG level was 2.2 mIU/mL and transvaginal US showed about 2.5×2.1-cm-sized heterogenous echogenic mass with no blood flow in right lateral wall of uterus, indicating successful treatment of previous AVM with embolic material. During the follow up, the patient remained asymptomatic. Follow-up transvaginal US showed about 1.7×1.4-cm-sized hyperechoic lesion with no flow, indicating remaining embolic material with no evidence of AVM and follow up CT scan after one month also showed no other abnormal finding.

Uterine AVM is a rare entity in gynecology, with fewer than 100 cases reported in the literature since Dubreuil and Loubat reported the first case of AVM in 1926 [1,2]. However, it is a potentially life-threatening condition in which patients present with profuse uterine bleeding, possibly causing hemodynamic instability. Thus, it is an important differential to be considered in patients presented with unexplained vaginal bleeding.

Recently the increasing awareness of uterine AVM as a pathological entity coupled with more widespread use of the appropriate diagnostic tools, it is more likely to be found and that uterine AVM may be more common than previously believed. Yet the true incidence of uterine AVM is unknown [2,3]. AVM is an abnormal connection between arteries and veins bypassing the capillary system. Distinction between arteries and veins is difficult because secondary intimal thickening occurs in the veins due to increased intraluminal pressure [1]. The abnormal communication between arteries and veins occur during the healing process, where usually a single artery join a single vein [1,2].

In our case, acquired form of AVM is strongly considered in the patient, given the absence of AVM lesion in initial imaging study, which newly appeared 7 days after using intrauterine instrumentation for laparoscopic surgery along with profuse vaginal bleeding. The possibility of the AVM lesion as the preexisting lesion cannot be completely excluded considering the false negative rate of imaging sacn for detecting abnormal finding. Yet in our case, as shown in the figure, the AVM lesion was quite prominent and uterus was examined in both sagittal and coronal section by transvaginal US. No complications were encountered during surgery and no other invasive procedures, such as curettage, that may cause uterine trauma was performed. The patient only received laparoscopic salpingectomy. We can only postulate that the uterine manipulator, ZUMI, used during the laparoscopic surgery to manipulate uterus have caused trauma in the right lateral wall of uterus, causing AVM.

In cases previously reported, patients experienced profuse vaginal bleeding within one months, and the symptom occurred after one week in our case [2,4]. There are no specific literature mentioning the period required to develop AVM after uterine trauma. But regarding the absence of previous vaginal bleeding and history of no other invasive procedure performed on the patient, we can carefully presume that AVM development was due to the use of the uterine manipulator, ZUMI.

The most important clinical manifestation is recurrent and profuse vaginal bleeding which can cause fatal outcome. Thus, early diagnosis and treatment is crucial. Traditionally, the diagnosis of uterine AVM was made by laparotomy or pathological examination of the uterus after hysterectomy have been performed. Subsequently, angiography became the gold standard for diagnosis. More recently, color doppler US has been used for obtaining a reliable diagnosis [5]. It. plays a significant role in demonstrating the vascular nature of anechoic uterine lesions. Nevertheless angiography remains as the gold standard, but it is rarely performed for diagnosis alone due to its invasive nature and is usually performed on patients requiring surgical intervention or embolization.

In uterine AVMs, gray-scale US shows the myometrium containing multiple tubular or spongy hypoechoic or anechoic spaces, with normal endometrium. However, other conditions such as retained products of conception, hemangioma, gestational trophoblastic disease, multi locular ovarian cysts or hydrosalpinx, may also present a similar appearance [6,7,8]. At color doppler US, the cystic spaces in AVM generate colour signals in a mosaic pattern representing turbulent flow [6,9]. Also, a normal myometrium show a peak systolic velocity (PSV) of 9-44 cm/sec and resistive index (RI) of 0.6-08, whereas AVM will show high velocity, mean PSV: 136 cm/sec and low resistance flow, mean RI: 0.3, along with low pulsatility of the arterial waveform and PSV consistent with an arterial flow pattern of venous flow [1,6,9].

In addition, other imaging methods such as contrast material enhanced CT and more recently, MRI have been proved to be useful. During the diagnosis, the differential diagnosis between the retained products and AVM is crucial because the treatment modalities are totally different, where curettage is required for retained products and selective embolization for AVM. Moreover, uterine curettage is contraindication in AVM, which can worsen vaginal bleeding as vessels of the vascular malformation can extend up to the endometrium [10,11].

Traditionally, hysterectomy was the treatment of choice, but recently wide use of angiographic embolization have allowed to avoid hysterectomy. However, hysterectomy still remains as the treatment of choice in post-menopausal patients or as an emergency treatment in life-threatening situations [8,12].

The successful uterine arterial embolization treatment was first described in 1986, since than it has been commonly used and has become the treatment of choice for hemodynamically stable patients, especially for patients with desire to preserve fertility [4]. It is highly effective, safe and rarely leads to complications [2,10]. In case of clinical failure, an underlying neoplastic disease should be considered.

The patient in our case was also successfully treated with uterine embolization which ceased vaginal bleeding and discharged without complications. The early diagnosis and treatment through angiography and embolization in these patients are crucial to spear fertility. Thus, despite its rare entity, uterine AVM should be considered in especially young patients requiring fertility preservation for early diagnosis and successful embolization. Acquired uterine AVM is rare and commonly thought to be a consequence of previous uterine trauma caused mainly by curettage or previous caesarean section. Nevertheless, through this case, we should consider the fact that even minor intrauterine instrumentation and simple manipulation of the uterus may also cause acquired uterine AVM, especially in pregnant women. Thus, although rare, uterine AVM should not be neglected in patients presented with profuse vaginal bleeding, and by performing early embolization, hysterectomy can be avoided to preserve fertility.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

The initial transvaginal ultrasonography showed no abnormal findings within the myometrium of the uterus (A). Transvaginal ultrasonography showed tubular lesion surrounded by anechogenic cystic space in the right lateral wall of myometrium with pulse rate of 71 beats/min (B) and computerized tomography scan showing contrast-opacified structure surrounded by low density lesion (C), suggesting arteriovenous malformation.

References

1. Hashim H, Nawawi O. Uterine arteriovenous malformation. Malays J Med Sci. 2013; 20:76–80.

2. Peitsidis P, Manolakos E, Tsekoura V, Kreienberg R, Schwentner L. Uterine arteriovenous malformations induced after diagnostic curettage: a systematic review. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011; 284:1137–1151.

3. Nasu K, Nishida M, Yoshimatsu J, Narahara H. Ectopic pregnancy after successful treatment with percutaneous transcatheter uterine arterial embolization for congenital uterine arteriovenous malformation: a case report. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2008; 278:171–172.

4. Elia G, Counsell C, Singer SJ. Uterine artery malformation as a hidden cause of severe uterine bleeding: a case report. J Reprod Med. 2001; 46:398–400.

5. Manolitsas T, Hurley V, Gilford E. Uterine arteriovenous malformation: a rare cause of uterine haemorrhage. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 1994; 34:197–199.

6. Polat P, Suma S, Kantarcy M, Alper F, Levent A. Color Doppler US in the evaluation of uterine vascular abnormalities. Radiographics. 2002; 22:47–53.

7. Grivell RM, Reid KM, Mellor A. Uterine arteriovenous malformations: a review of the current literature. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2005; 60:761–767.

8. Huang MW, Muradali D, Thurston WA, Burns PN, Wilson SR. Uterine arteriovenous malformations: gray-scale and Doppler US features with MR imaging correlation. Radiology. 1998; 206:115–123.

9. Sugiyama T, Honda S, Kataoka A, Komai K, Izumi S, Yakushiji M. Diagnosis of uterine arteriovenous malformation by color and pulsed Doppler ultrasonography. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1996; 8:359–360.

10. Maleux G, Timmerman D, Heye S, Wilms G. Acquired uterine vascular malformations: radiological and clinical outcome after transcatheter embolotherapy. Eur Radiol. 2006; 16:299–306.

11. Halperin R, Schneider D, Maymon R, Peer A, Pansky M, Herman A. Arteriovenous malformation after uterine curettage: a report of 3 cases. J Reprod Med. 2007; 52:445–449.

12. Vogelzang RL, Nemcek AA Jr, Skrtic Z, Gorrell J, Lurain JR. Uterine arteriovenous malformations: primary treatment with therapeutic embolization. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1991; 2:517–522.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download