Abstract

We report a case of Cushing syndrome secondary to adrenal adenoma presenting with hypertension and oligohydramnios during pregnancy. The tumor was confirmed by magnetic resonance imaging at 28 week 3 day weeks of pregnancy and was removed surgically at 29 week 1 day weeks of gestation. After surgery, hypertension subsided and amniotic fluid volume returned to normal range. The gravid woman subsequently delivered a healthy infant at term.

Cushing syndrome (CS) is rare in pregnancy because hypercortisolism often induces menstrual disturbance leading to infertility [1]. The most common cause of CS during pregnancy is adrenal adenoma, followed by pituitary etiology, and adrenal carcinoma [2].

Undetected cases of CS during pregnancy is associated with significant maternal and fetal complications including hypertension, gestational diabetes, heart failure, pulmonary edema, spontaneous abortion, preterm labor and fetal growth restriction [3-7]. However, this disease is difficult to diagnose and is often misdiagnosed in pregnancy because radiologic modalities are limited and the symptoms such as hypertension or excessive weight gain mimic those of complicated pregnancies such as preeclampsia and gestational diabetes. Even after detection of CS, management of CS remains controversial especially in the early third trimester of pregnancy [4].

Here, we report a case of CS presenting with hypertension and oligohydramnios secondary to an adrenal adenoma which was surgically treated during the third trimester of pregnancy.

A 38-year-old multigravida (G3P0) woman was referred to our institution at 27 week 1 day weeks of pregnancy for evaluation of borderline blood pressure (range, 135/70-158/80 mm Hg) and generalized edema which developed 1 week prior. At her first visit to our institution, she complained excessive weight gain of over 5 kg in the last week and irregular uterine contractions. Her blood pressure and body mass index were 133/75 mm Hg and 31.2 kg/m2, respectively. A urinary dipstick test revealed 1+ proteinuria. In her past medical history, conization was performed for cervical carcinoma in situ 5 years ago. In her prenatal exams, the result of amniocentesis showed 46, XX and other obstetrical laboratory tests were normal except 50 g oral glucose screening test (145 mg/dL) which was confirmed to be normal by 100 g oral glucose tolerance test. Ultrasonography showed a single fetus with 1,107 g of estimated weight in cephalic presentation, decreased amniotic fluid volume with amniotic fluid index (AFI) 5 cm and shortened cervical length of 1.95 cm. The fetus showed reactive fetal heart rate pattern on non-stress test. She was admitted for evaluation under the suspicion of preeclampsia and preterm labor with short cervical length.

After hospitalization, a diagnostic workup for preeclampsia was performed and the results were as follows. Complete blood cell count was normal and other laboratory tests including serum electrolyte, renal function test, liver enzyme and coagulation were all within normal range except potassium level (2.7 mmol/L). Initial 24-hour urine protein collection was 189.1 mg/day and repeated urine collection revealed 207.55 mg/day. Namely, the results were not consistent with preeclampsia. In addition, she had Cushingoid characteristics-moon face, central obesity, buffalo hump, abdominal and lower limb striae and hypokalemia. On the basis of physical findings and hypokalemia, we performed diagnostic tests for CS including serum cortisol, 24-hour urinary cortisol excretion, plasma adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), and an overnight 1mg dexamethasone suppression test. Serum basal cortisol level was 27.3 µg/dL (normal in third trimester 1.8-26.0 µg/dL) and 24-hour urinary free cortisol excretion level was 1,900 µg/24 hr (normal in third trimester < 20.16 µg/dL [4]), and plasma ACTH levels were 3.8 pg/mL (normal range: 0.0-46 pg/mL). As expected, the serum cortisol (23.5 µg/dL) was not suppressed after 1 mg overnight dexamethasone suppression.

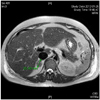

Although, there was no definite criterion for interpreting a hormonal study for CS in pregnancy, the diagnostic evaluation revealed remarkable increase of urinary free cortisol. Therefore, magnetic resonance image (MRI) of adrenal gland and sellar were performed at 28 week 4 day. Adrenal gland MRI revealed a 2.5 cm × 2.0 cm × 2.5 cm tumor in the right adrenal gland (Fig. 1). Cranial MRI scanning showed no abnormal finding.

Considering the gestational age (29 week 1 day, the risk of prematurity) of the fetus and the opinion of the endocrine surgeon, immediate adrenalectomy might be helpful to the patient rather than the delay of operation; we decided to perform direct surgical treatment instead of medical treatment with metyrapone. At 29 week 1 day, unilateral adrenalectomy was done under laparotomy using laparoscopic devices such as Harmonic scalpel and graspers to minimize uterine manipulation. Histopathologic examination confirmed a benign cortical adenoma (Fig. 2). After surgery, there were no significant uterine contractions and tocolytic agent was not used. Glucocortioid was administered for 7 days to avoid adrenal crisis as follow. At the day of surgery and the day after surgery, 100 mg of hydrocortisone was administered intravenously three times in a day. Thereafter same dose of hydrocortisone was injected intravenously twice in a day for two days and the dose of hydrocortisone was reduced to 50 mg twice in a day. After that, we stopped intravenous steroid injection and administered 10 mg of oral prednisolone to her twice in a day. Her blood pressure started to decrease after surgery and she was discharged on seventh day after operation. She maintained her medication for seven days more after discharge.

Two weeks following surgery, her blood pressure had returned to normal and amniotic fluid volume also returned to normal AFI 15 cm on ultrasonography. The 24 hour urinary cortisol level decreased from 1,900 µg to 113 µg. ACTH stimulation test evaluating her remnant adrenal function suggested mild adrenal gland dysfunction; therefore, oral prednisolone therapy (2.5 mg in a day) was maintained. At 38 week 4 day weeks of gestation, premature rupture of membranes developed and she vaginally delivered a 2,450 g female infant with Apgar scores of 9 at 1 minute and 9 at 5 minutes. The level of cortisol in cord blood at birth was normal.

Although CS during pregnancy is extremely rare, it is associated with significant maternal and fetal morbidity [2-6]. However, it is often hard to diagnose CS in pregnant women by hormonal study and there are no definite criteria of how the diagnosis should be established to allow for pregnancy associated with hypercortisolism [8]. Because a pregnancy dramatically influences on the maternal hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis [6]. Indeed, total and free plasma cortisol concentrations rise in parallel during gestation. Plasma cortisol is reported to be 2- to 3-fold higher in pregnant woman in comparison with non-pregnant controls [6]. Also, urinary free cortisol (UFC) excretion increases since serum cortisol rises through the course of gestation [6,9]. Both circulating and UFC levels increase steadily during gestation, reaching values similar to those found in CS [9,10]. In addition, the dexamethasone suppression test in pregnant women has a higher false positive rate compared with non pregnant women due to blunted inhibition of cortisol secretion by dexamethasone during pregnancy [2,6,9]. Meanwhile, diurnal rhythm of plasma cortisol is preserved in pregnancy, so midnight cortisol level may be helpful in establishing the diagnosis [5]. Also, a literature reported that a mean eightfold increase in urinary free cortisol accompanies cases of CS during pregnancy [9]. Although overnight 1 mg dexamethasone suppression test shows a higher false positive rate, extremely increased level of 24-hour urinary cortisol in our patient made CS strongly suspected. After consulting to the endocrinologist, we decided to do adrenal gland and cranial MRI rather than running other laboratory hormonal tests.

In this case, the patient presented with hypertension and oligohydramnios. The decreased amniotic fluid volume was normalized after the adrenalectomy. We cannot explain the mechanism of oligohydramnios, but we conjecture generalized edema and decreased intravascular volume of patient might have contributed to the development of oligohydramnios.

Management of the pregnant patient with hypercortisolism includes identifying the origin of hormone production and establishing proper therapy. If the cause of CS is an adrenal adenoma, the therapeutic modalities are unilateral adrenalectomy during pregnancy or medical treatment followed by surgery after delivery [5]. The optimal timing for adrenalectomy has not been established but the operation during the second trimester has been preferred because it is safe and significantly reduces maternal fetal morbidity [11]. In the third trimester, conservative treatment and early delivery was preferred [12] but Shaw et al. [4] successfully treated a patient with CS at 31 weeks by unilateral adrenalectomy. In our case, the patient was diagnosed to be CS at 28 weeks of pregnancy, still remote from term, hence we decided upon surgical treatment in spite of enlarged uterus hindering operation. As we thought laparoscopic operation might not be feasible, we had to do laparotomy. However, we could reduce uterine manipulation by the benefit of using laparoscopic instruments during the operation.

Medical treatment using metyrapone, ketoconazole, cyproheptadine and aminoglutethimide may be considered in patient with serious symptoms of hypercortisolism, when surgical therapy is contraindicated or as an interim therapy before surgery [5,13]. Although no adverse fetal or neonatal side effects have been reported, experiences with these drugs are relatively limited [13]. Among these drugs, metyrapone and ketoconazole have been used successfully, but cyproheptadine is ineffective and not recommended. Aminoglutethimide is associated with fetal masculinization and contraindicated in pregnancy [5].

In the literature, most cases of Cushing's disease diagnosed during the early third trimester were lead to iatrogenic preterm birth and surgical treatment. However in our case, pregnancy was maintained to full term after surgical treatment.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Borna S, Akbari S, Eftekhar T, Mostaan F. Cushing's syndrome during pregnancy secondary to adrenal adenoma. Acta Med Iran. 2012; 50:76–78.

2. Lekarev O, New MI. Adrenal disease in pregnancy. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011; 25:959–973.

3. Chico A, Manzanares JM, Halperin I, Martinez de Osaba MJ, Adelantado J, Webb SM. Cushing's disease and pregnancy: report of six cases. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1996; 64:143–146.

4. Shaw JA, Pearson DW, Krukowski ZH, Fisher PM, Bevan JS. Cushing's syndrome during pregnancy: curative adrenalectomy at 31 weeks gestation. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2002; 105:189–191.

5. Choi WJ, Jung TS, Paik WY. Cushing's syndrome in pregnancy with a severe maternal complication: a case report. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2011; 37:163–167.

6. Vilar L, Freitas Mda C, Lima LH, Lyra R, Kater CE. Cushing's syndrome in pregnancy: an overview. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol. 2007; 51:1293–1302.

7. Buescher MA, McClamrock HD, Adashi EY. Cushing syndrome in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1992; 79:130–137.

8. Lindsay JR, Nieman LK. Adrenal disorders in pregnancy. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2006; 35:1–20.

9. Lindsay JR, Jonklaas J, Oldfield EH, Nieman LK. Cushing's syndrome during pregnancy: personal experience and review of the literature. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005; 90:3077–3083.

10. Carr BR, Parker CR Jr, Madden JD, MacDonald PC, Porter JC. Maternal plasma adrenocorticotropin and cortisol relationships throughout human pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1981; 139:416–422.

11. Bevan JS, Gough MH, Gillmer MD, Burke CW. Cushing's syndrome in pregnancy: the timing of definitive treatment. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1987; 27:225–233.

12. Polli N, Pecori Giraldi F, Cavagnini F. Cushing's syndrome in pregnancy. J Endocrinol Invest. 2003; 26:1045–1050.

13. Bednarek-Tupikowska G, Kubicka E, Sicinska-Werner T, Kazimierczak A, Winowski J, Tupikowska M, et al. A case of Cushing's syndrome in pregnancy. Endokrynol Pol. 2011; 62:181–185.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download