Abstract

Tooth transposition is a disorder in which a permanent tooth develops and erupts in the normal position of another permanent tooth. Fusion and gemination are developmental disturbances presenting as the union of teeth. This article reports the nonsurgical retreatment of a very rare case of fused teeth with transposition. A patient was referred for endodontic treatment of her maxillary left first molar in the position of the first premolar, which was adjacent to it on the distobuccal side. Orthopantomography and periapical radiography showed two crowns sharing the same root, with a root canal treatment and an associated periapical lesion. Tooth fusion with transposition of a maxillary molar and a premolar was diagnosed. Nonsurgical endodontic retreatment was performed. At four yr follow-up, the tooth was asymptomatic and the radiolucency around the apical region had decreased, showing the success of our intervention. The diagnosis and treatment of fused teeth require special attention. The canal system should be carefully explored to obtain a full understanding of the anatomy, allowing it to be fully cleaned and obturated. Thermoplastic techniques were useful in obtaining hermetic obturation. A correct anatomical evaluation improves the set of treatment options under consideration, leading to a higher likelihood of esthetically and functionally successful treatment.

Developmental anomalies of dentition are uncommon in clinical practice.1 Posterior transpositions are extremely rare, and even more so when associated with fusion. This combination has not been previously reported in the literature. Tooth transposition is a disorder in which a permanent tooth develops and erupts in the normal position of another permanent tooth.2 Fusion and gemination are developmental disturbances presenting as the union of teeth.134 Fusion occurs when two teeth buds join, while gemination results from the attempted division of one tooth bud into two.5 Fusion between teeth always involves dentin and may result in an unusually large tooth and the union of both crowns or only of the roots. The root canals may be either independent or joined.35

The clinical management of developmental anomalies is typically complex, given the occurrence of malocclusion, esthetic issues, and predisposition to further oral disorders.6 Diagnosis, treatment, and rehabilitation are often challenging due to the uneven presentation of the crown and distorted endodontic anatomy.7 The purpose of this article is to present a case of successful nonsurgical root canal retreatment of a very rare case of fusion with transposition of the posterior teeth.

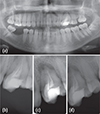

A 21 year old female patient presented with pain in the left maxilla and recurrent abscesses in this region. The patient's medical history was noncontributory, and her previous dental history included an extraction on the lower right quadrant and a root canal treatment in the upper left quadrant. The clinical examination revealed a tooth similar to a molar in the position of the first left premolar, which was adjacent to it on the distobuccal side. The tooth was sensitive to percussion. Periodontal probing revealed normal values of 1 mm on the buccal, palatal, and mesial aspects and 3 mm on the distal aspect. Orthopantomography and periapical radiography showed two crowns sharing the same root, with a root canal treatment and an associated periapical lesion (Figure 1). Based on the clinical and radiographic information, symptomatic apical periodontitis was diagnosed in a previously treated tooth. The treatment plan involved exploration of the complete canal system and nonsurgical endodontic retreatment.

After the patient provided informed consent, the tooth was anesthetized and isolated with a rubber dam. After opening the access cavity of the molar-like tooth and performing irrigation with 2.5% sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl), the gutta-percha was removed using ProTaper Universal retreatment files (Dentsply Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland) and the diagnosis of fused teeth was confirmed. An access cavity was opened on the premolar (Figure 2a), showing that the canal system was fused with that of the molar-like tooth (Figure 2b). The distobuccal and palatal canals were also fused (Figure 2c). After shaping with a finishing file ProTaper Universal F3, two canals persisted: a mesiobuccal canal and another canal with a shape similar to that of a C-shaped canal (Figure 2d). The root canals were dried with sterile paper points (Dentsply Maillefer), a calcium hydroxide paste (Calcicur-VOCO, Cuxhaven, Germany) was applied, and the access cavity was temporarily sealed with IRM (Dentsply, Konstanz, Germany).

After one month, the patient returned and the calcium hydroxide paste was removed. Irrigation was performed with 2.5% NaOCl, passive ultrasonic irrigation was performed with a size 15 file, and the area was dried with sterile paper points. AH Plus sealer (Dentsply) was applied with a lentulo and the excess was removed with paper points (Figure 3a). The root canal filling was done with thermoplasticized gutta-percha systems, using Thermafill (Dentsply Maillefer) in the mesiobuccal canal and Thermafill followed by BeeFill (VDW, Munich, Germany) with vertical condensation in the quasi-C-shaped canal (Figure 3b). A postoperative radiograph (Figure 3c) confirmed that the root canal system filling was complete, with some lateral canals appearing in the image, showing the complexity of the anatomy. The crown was restored permanently with a ceramic onlay, improving the esthetics and strengthening the tooth (Figure 4).

At the four year follow-up, the tooth was asymptomatic and less radiolucency was observed around the apical region in comparison with the preoperative radiographs (Figure 3d).

This case report presents the successful endodontic management of fused teeth with transposition of the maxillary first molar and premolar, which were fused on the distobuccal side of the first molar.

Transposition of the teeth is uncommon, and most cases involve the canine. The prevalence of transposition has been estimated to be 0.03 - 0.25% in the general population.2 In particular, posterior transpositions such as that of our patient are extremely rare, and even more so when associated with the phenomenon of fusion. In fact, to our knowledge, this is the first report of a case of tooth fusion with transposition.

The prevalence of fusion in the permanent dentition has been estimated to be 0.1 - 1% and 0.5 - 2.5% in the primary dentition.8910 Most case reports concerning the permanent teeth involve the anterior teeth, while fewer studies have presented posterior maxillary cases of fusion.111213 The etiology of this malformation remains uncertain. The influence of pressure or physical forces prompting close contact between tooth follicles, hereditary conditions, and apparent racial differences have been suggested as possible contributors to its occurrence.1415

Clinically, a case of fusion may resemble gemination. In order to differentiate between fusion and gemination, some authors have proposed that, when counting the teeth, an anomalous crown should be counted as one tooth. According to this method, a full complement of teeth points towards gemination, while fusion is suggested by a less than normal count of teeth.161718 However, in clinical practice, the presence of supernumerary teeth may preclude distinguishing between cases of fusion and gemination. The difficulty differentiating a fused from a geminated tooth led Brook et al. to propose a neutral term, referring to these anomalies as 'double teeth',19 and arguing that mere recognition of this anomaly should be sufficient from the point of view of treatment.20

The present case was classified as fused teeth with transposition, because on intraoral inspection and on orthopantomography, if the tooth with an anomaly was counted as a single tooth, one tooth (the first maxillary left molar) was missing in the maxilla. Instead, in the position of the first premolar, an anomalous tooth that resembled a molar was found adjacent to a premolar. The patient's previous treatment failed due to missed parts of the canal system that were left untouched, allowing reinfection. Cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) would have been helpful for understanding the anatomy, since it is the most useful tool for analyzing teeth with uncommon morphology. However, CBCT was not available when the treatment was performed. Therefore, radiographs with a range of angulations and careful exploration during preparation of the access cavity were used in the initial treatment planning (Figure 2).

This report shows that a careful clinical and radiographic assessment is essential for the successful endodontic treatment of anomalous teeth,17 because it is imperative to evaluate the altered anatomy correctly. The endodontic treatment of such teeth is frequently challenging due to the position of the tooth, its complex anatomy, and the difficultly of performing isolation with a rubber dam.11 Its success relies on the careful preparation of the access cavity and the cleaning, shaping, and three-dimensional filling of the root canal system. Despite all precautions, in some instances complications may occur during treatment, such as perforations12 requiring the use of materials such as mineral trioxide aggregate or biodentine to repair the communication between the pulp and periodontal tissues.

Although the root canal preparation of double teeth may be difficult, frequent irrigation with sodium hypochlorite and the use of thermoplasticized gutta-percha techniques were a good solution in our case. Continuous wave compaction would also have been an option for obturation of this tooth. The thorough root canal filling using Thermafill and BeeFill reached the lateral canals, as shown in Figure 3c, which may prevent future complications. Furthermore, retreatment avoided extraction and allowed the patient to retain the affected tooth. Despite only having one root, two individualized crowns were achieved, with esthetic and functional benefits. A coverage crown would have been the best choice to provide protection from occlusal forces; however, the second premolar was too buccal. Therefore, in order to maintain the esthetic results without destroying or weakening the tooth, a ceramic onlay was performed, with the coverage limited to the middle of the crown (Figures 4b and 4d). Occlusion before treatment was made only with the molar-like tooth (Figure 4a). After restoration, occlusal contacts were distributed between the two crowns that resulted from treatment (Figure 4b).

At four year follow-up, the tooth was asymptomatic and the radiolucency around the apical region had decreased, showing the success of our intervention.

A successful case of the nonsurgical endodontic retreatment of fused teeth with transposition has been presented, where marked anatomic alterations were visible on direct observation and on radiographs. Despite the presence of two crowns, only a single root canal system was found. Although CBCT plays an important role in diagnosis, if it cannot be performed, the canal system should be carefully explored to obtain a complete understanding of the anatomy, in order to fully clean and obturate the canals. Thermoplastic techniques were useful in accomplishing hermetic obturation and preventing reinfection. The anatomy of the root canal system of fused teeth requires special attention in the diagnosis and treatment planning, making careful clinical and radiographic examinations essential for the successful endodontic treatment of such cases.

Figures and Tables

Figure 1

Preoperative evaluation. (a) Preoperative orthopantomography; (b - d) Preoperative periapical radiographs with different angulations.

Figure 2

Complexity of anatomy. (a) Access cavities; (b) Communication between the canal systems of the molar and premolar; (c) Fusion between distobuccal and palatal canals; (d) The remaining two canals after shaping.

References

1. Knezević A, Travan S, Tarle Z, Sutalo J, Janković B, Ciglar I. Double tooth. Coll Antropol. 2002; 26:667–672.

2. Kavadia-Tsatala S, Sidiropoulou S, Kaklamanos EG, Chatziyanni A. Tooth transpositions associated with dental anomalies and treatment management in a sample of orthodontic patients. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2003; 28:19–25.

3. Tannenbaum KA, Alling EE. Anomalous tooth development. Case reports of gemination and twinning. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1963; 16:883–887.

4. Cho KM, Jang JH, Park SH. Clinical management of a fused upper premolar with supernumerary tooth: a case report. Restor Dent Endod. 2014; 39:319–323.

5. Gadimli C, Sari Z. Interdisciplinary treatment of a fused lower premolar with supernumerary tooth. Eur J Dent. 2011; 5:349–353.

6. G S, Jena A. Prevalence and incidence of gemination and fusion in maxillary lateral incisors in odisha population and related case report. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013; 7:2326–2329.

7. Gallottini L, Barbato Bellatini RC, Migliau G. Endodontic treatment of a fused tooth. Report of a case. Minerva Stomatol. 2007; 56:633–638.

8. Aryanpour S, Bercy P, Van Nieuwenhuysen JP. Endodontic and periodontal treatments of a geminated mandibular first premolar. Int Endod J. 2002; 35:209–214.

9. Liang RZ, Wu JT, Wu YN, Smales RJ, Hu M, Yu JH, Zhang GD. Bilateral maxillary fused second and third molars: a rare occurrence. Int J Oral Sci. 2012; 4:231–234.

10. Salem Milani A. Endodontic management of a fused mandibular second molar and paramolar: a case report. Iran Endod J. 2010; 5:131–134.

11. Song CK, Chang HS, Min KS. Endodontic management of supernumerary tooth fused with maxillary first molar by using cone-beam computed tomography. J Endod. 2010; 36:1901–1904.

12. Weinstein T, Rosano G, Del Fabbro M, Taschieri S. Endodontic treatment of a geminated maxillary second molar using an endoscope as magnification device. Int Endod J. 2010; 43:443–450.

13. Asgary S. Endodontic treatment of a maxillary second molar with developmental anomaly: a case report. Iran Endod J. 2007; 2:73–76.

15. Rotstein I, Moshonov J, Cohenca N. Endodontic therapy for a fused mandibular molar. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1997; 13:149–151.

16. Milazzo A, Alexander SA. Fusion, gemination, oligodontia, and taurodontism. J Pedod. 1982; 6:194–199.

17. Yücel AC, Güler E. Nonsurgical endodontic retreatment of geminated teeth: a case report. J Endod. 2006; 32:1214–1216.

18. Camm JH, Wood AJ. Gemination, fusion and supernumerary tooth in the primary dentition: report of case. ASDC J Dent Child. 2015; 56:60–61.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download