Abstract

Traumatic injuries to an immature permanent tooth may result in cessation of dentin deposition and root maturation. Endodontic treatment is often complicated in premature tooth with an uncertain prognosis. This article describes successful treatment of two traumatized maxillary central incisors with complicated crown fracture three months after trauma. The radiographic examination showed immature roots in maxillary central incisors of a 9-year-old boy with a radiolucent lesion adjacent to the right central incisor. Apexogenesis was performed for the left central incisor and revascularization treatment was considered for the right one. In 18-month clinical and radiographic follow-up both teeth were asymptomatic, roots continued to develop, and periapical radiolucency of the right central incisor healed. Considering the root development of these contralateral teeth it can be concluded that revascularization is an appropriate treatment method in immature necrotic teeth.

Traumatic injuries to the teeth may result in pulpal and periapical disease. Most dental traumas occur in the 7 - 10 year-old age group with incomplete apical root development.1,2 Complicated crown fractures which involve the enamel, dentin and pulp occur in 0.9 - 13% of all dental injuries.3,4 Vital pulp therapy (VPT) is the treatment of choice for traumatized immature teeth with pulp exposure.5,6 VPT allows continuation of root development, which leads to apical closure and strengthening of the root structure.7 If the pulp vitality of a traumatized immature tooth is lost, the treatment will be a challenge in endodontics. It is difficult to obtain an appropriate apical seal in these teeth by using the conventional obturation methods. Furthermore, thin root canal walls make the teeth susceptible to future fractures.8 Several different clinical methods have been used to treat these teeth, such as long-term calcium hydroxide apexification and one-visit apexification (use of a material to create an artificial barrier). Recently, regenerative endodontic procedures have drawn much attention. The advantage of this treatment modality over apexification is that it allows root maturation to continue by generating vital tissue.9

This case report presented regenerative therapy of a traumatized immature maxillary central incisor with apical abscess. The outcome of root development in this tooth was compared with contralateral tooth that treated using vital pulp therapy.

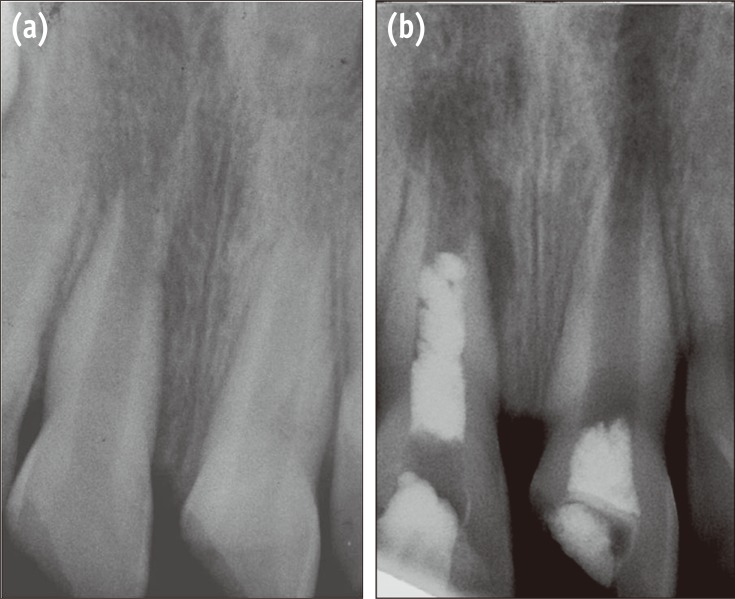

A 9-year-old boy was referred to the Department of Endodontics with pain on chewing and localized swelling on the anterior region of maxilla and a history of prior impact trauma three months previously. His medical history was non-contributory. Clinical examination showed complicated crown fracture on both maxillary central incisors. A large pulpal exposure, sensitivity to palpation and percussion and also localized swelling on the buccal mucosa of the right central incisor was observed. Cold thermal test elicited no response in this tooth. Left central incisor with a pinpoint pulpal exposure had no sensitivity in periapical tests and showed lingering painful response to cold test. Radiographic examination revealed that the fractured teeth had immature apices, and a radiolucent periapical lesion was observed adjacent to the right central incisor (Figure 1a). Based on clinical and radiographic examinations, the definitive diagnosis was irreversible pulpitis in the left central incisor and pulpal necrosis with symptomatic apical abscess in the right central incisor. Considering the immaturity of the teeth, the first treatment option was vital pulp therapy for the left central incisor and revascularization of the right one.

Under local anesthesia with 2% Lidocaine and 1 : 800,000 epinephrine (Xylocaine 2%, Dentsply, Addlestone, UK) and rubber dam isolation, an access cavity was prepared for the left central incisor. Coronal pulp tissues were removed by using a high-speed sterile long shank round diamond bur under copious water spray. The area was rinsed with normal saline solution and hemostasis was achieved by a cotton pellet moistened with 5% sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl). White Mineral Trioxide Aggregates (ProRoot MTA, Dentsply, Tulsa, OK, USA) powder was mixed with distilled water according to manufacturer's instructions and placed without pressure over the exposed clot-free pulpal wound (Figure 1b). The material was gently patted down with a moist cotton pellet. Then a moistened cotton pellet was placed over MTA and the tooth was temporarily filled with Cavit (Asia Chemi Teb Co., Tehran, Iran). One day later, the teeth were restored permanently with composite resin (Filtek Z350, 3M ESPE, St. Paul, MN, USA).

An access cavity was prepared for the right central incisor using the same procedure. On entering the pulp chamber, purulent drainage was observed. Length was estimated radiographically using a size #15 K-file (K-file, Mani Corp., Tokyo, Japan). The canal was passively irrigated with 20 mL of 5.25% NaOCl and gently dried with paper points. A creamy mixture of equal proportions of ciprofloxacin, metronidazole and minocycline, as described by Hoshino et al., was placed in the root canal with a #25 K-file up to 3 mm short of the radiographic apex.10 The access cavity was sealed temporarily with Cavit. After 3 weeks the patient was asymptomatic and the localized swelling had resolved. The tooth was anesthetized with a local injection of 3% plain Mepivacaine (Septodont, Cedex, France) without vasoconstrictor. After rubber dam isolation and removal of Cavit dressing, the antibiotic dressing material was removed by irrigation with 10 mL of 5.25% NaOCl and saline. The canal was then dried with paper points. A #40 K-file was used to irritate the apical tissues to create some bleeding into the root canal. The bleeding was allowed to reach the middle part of the canal. Ten minutes later, after the formation of a blood clot, white MTA was mixed and placed over the clot carefully (Figure 1b). A moistened cotton pellet was placed over MTA and the tooth was restored temporarily with Cavit. One day later the patient was referred for permanent restoration of this tooth.

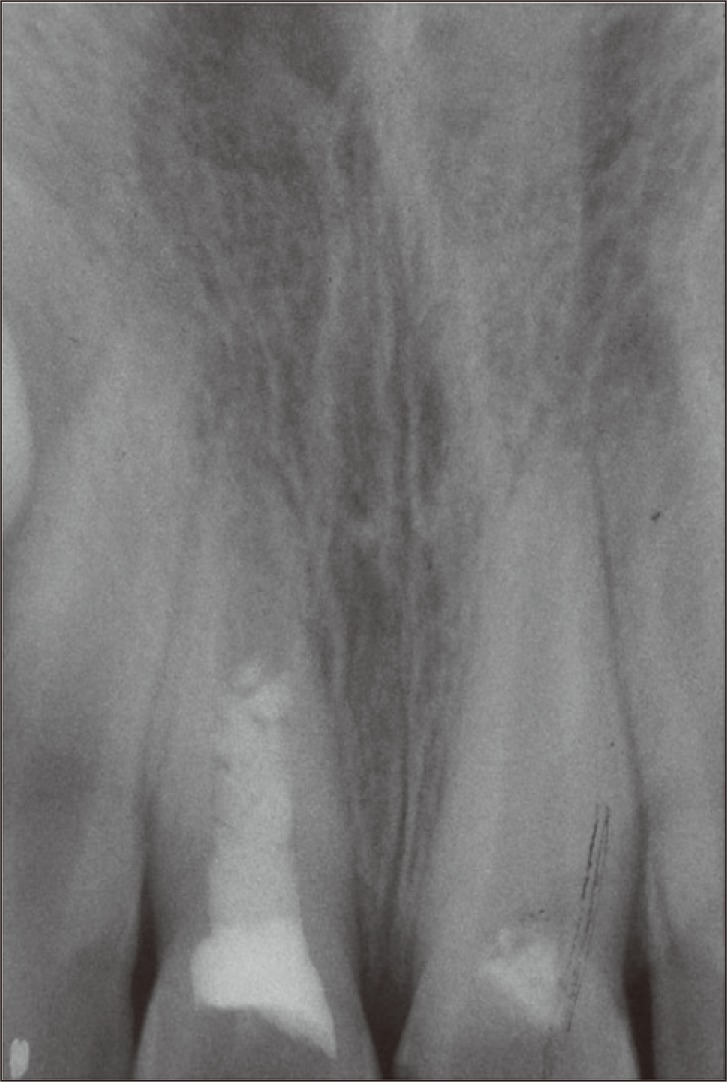

The patient was recalled 6, 12 and 18 months after the treatment. In clinical examination, the teeth were asymptomatic. In radiographic examinations, both teeth showed increased root lengths and apical closure. Root wall thickness had also increased, but the left central incisor showed greater improvements. The radiolucent lesion adjacent to the right central incisor had healed (Figures 2 and 3).

An essential requirement for successful vital pulp therapy is a healthy pulp.11,12 As time between exposure and treatment increases, pulp removal must be extended apically to ensure that inflamed pulp tissue has been removed.13 In the present case, considering the long period between the time of injury and therapy, cervical pulpotomy was carried out for the left central incisor. A proper pulp dressing is important for VPT. Several studies have shown favorable outcomes for MTA pulpotomies in human teeth.14,15 The left central incisor in this report also showed successful outcome without any need for further endodontic intervention.

A complicated crown fracture will always result in pulp necrosis if left untreated.16 Too large pulpal exposure in the right central incisor increased the chances of bacterial contamination of the pulp and led to pulpal necrosis. The common method traditionally used for the treatment of necrotic open apex teeth has been apexification. However, apexification with calcium hydroxide has several disadvantages, including a lengthy treatment period, susceptibility to fracture and coronal microleakage during treatment period.13,17,18 Furthermore, traditional and one-visit apexification does not promote continued development of the root, leading to the risk of fracture of a short and weakened root.19 Revascularization has been considered an alternative treatment modality. If the root canal of a necrotic infected tooth is effectively disinfected, regeneration should occur in the presence of a suitable scaffold.20 The blood clot in the apical part of the canal can act as a scaffold and might also contain growth and differentiation factors which might be crucial for successful proliferation and differentiation of stem cells.21,22 In order to obtain appropriate bleeding Petrino et al. suggested using non-epinephrine local anesthetics, as carried out in this case.23

Studies have shown that local application of a mixture of ciprofloxacin, metronidazole, and minocycline is effective against endodontic pathogens.10,24 In the present case, the root canal was irrigated with 5.25% NaOCl and filled with the triple antibiotic dressing. After 3 weeks, the teeth were asymptomatic. It seems that this antibacterial protocol can disinfect the root canal effectively. The importance of a bacterial-tight seal for successful VPT and also revascularization has been well documented.11,25 In the case of apexogenesis, one day after the pulpotomy procedure, the tooth was restored by using dentin-bonding composite resin. In the revascularization case, a double seal over the blood clot, MTA and a resin-bonding restoration, recommended in several studies, was used.23,25,26

In this case report, it was possible to compare the outcomes of regeneration therapy and VPT in two contralateral teeth. Both teeth showed approximately similar increased root lengths, root wall thickness, and apical closure. However, it should be pointed out that the continued root development after apexogenesis is a normal physiological process because the radicular pulp tissue is vital. But the tissues inside the canal space of immature teeth with apical periodontitis after revascularization process have been described as periodontal ligament-like connective tissue and the gained root length and thickening are the result of newly formed cementum or cementum-like tissues.9,21,27,28

In conclusion, the authors believe that revascularization therapy is an appropriate treatment for necrotic immature teeth with apical periodontitis. However, the case reports on endodontic regeneration have used varying treatment methods and no study has analyzed the overall results, so further clinical trials are required to prepare a uniform treatment strategy.

References

1. Andreasen JO, Ravn JJ. Epidemiology of traumatic dental injuries to primary and permanent teeth in a Danish population sample. Int J Oral Surg. 1972; 1:235–239. PMID: 4146883.

2. Bastone EB, Freer TJ, McNamara JR. Epidemiology of dental trauma: a review of the literature. Aust Dent J. 2000; 45:2–9. PMID: 10846265.

3. Canakci V, Akgül HM, Akgül N, Canakci CF. Prevalence and handedness correlates of traumatic injuries to the permanent incisors in 13-17-year-old adolescents in Erzurum, Turkey. Dent Traumatol. 2003; 19:248–254. PMID: 14708648.

4. Tapias MA, Jiménez-García R, Lamas F, Gil AA. Prevalence of traumatic crown fractures to permanent incisors in a childhood population: Móstoles, Spain. Dent Traumatol. 2003; 19:119–122. PMID: 12752531.

5. Witherspoon DE. Vital pulp therapy with new materials: new directions and treatment perspectives-permanent teeth. J Endod. 2008; 34:S25–S28. PMID: 18565368.

7. Katebzadeh N, Dalton BC, Trope M. Strengthening immature teeth during and after apexification. J Endod. 1998; 24:256–259. PMID: 9641130.

8. Waterhouse PJ, Whitworth JM, Camp JH, Fuks AB. Chapter 23, Pediatric endodontics: endodontic treatment for the primary and young permanent dentition. In : Hargreaves KM, Cohen S, editors. Cohen's Pathways of the pulp. 10th ed. St Louis: Mosby Elsevier;2011. p. 808–857.

9. Yamauchi N, Yamauchi S, Nagaoka H, Duggan D, Zhong S, Lee SM, Teixeira FB, Yamauchi M. Tissue engineering strategies for immature teeth with apical periodontitis. J Endod. 2011; 37:390–397. PMID: 21329828.

10. Hoshino E, Kurihara-Ando N, Sato I, Uematsu H, Sato M, Kota K, Iwaku M. In-vitro antibacterial susceptibility of bacteria taken from infected root dentine to a mixture of ciprofloxacin, metronidazole and minocycline. Int Endod J. 1996; 29:125–130. PMID: 9206436.

11. Tronstad L, Mjör IA. Capping of the inflamed pulp. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1972; 34:477–485. PMID: 4625987.

12. Swift EJ Jr, Trope M. Treatment options for the exposed vital pulp. Pract Periodontics Aesthet Dent. 1999; 11:735–739. PMID: 10635232.

13. Trope M. Chapter 36, Endodontic considerations in dental trauma. In : Ingle JI, Bakland LK, Baumgartner JC, editors. Ingle's Endodontics. 6th ed. Hamilton: BC Decker Inc;2008. p. 1330–1357.

14. Witherspoon DE, Small JC, Harris GZ. Mineral trioxide aggregate pulpotomies: a case series outcomes assessment. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006; 137:610–618. PMID: 16739540.

15. Barrieshi-Nusair KM, Qudeimat MA. A prospective clinical study of mineral trioxide aggregate for partial pulpotomy in cariously exposed permanent teeth. J Endod. 2006; 32:731–735. PMID: 16861071.

16. Kakehashi S, Stanley HR, Fitzgerald RJ. The effects of surgical exposures of dental pulps in germ-free and conventional laboratory rats. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1965; 20:340–349. PMID: 14342926.

17. Andreasen JO, Farik B, Munksgaard EC. Long-term calcium hydroxide as a root canal dressing may increase risk of root fracture. Dent Traumatol. 2002; 18:134–137. PMID: 12110105.

18. Holden DT, Schwartz SA, Kirkpatrick TC, Schindler WG. Clinical outcomes of artificial root-end barriers with mineral trioxide aggregate in teeth with immature apices. J Endod. 2008; 34:812–817. PMID: 18570985.

19. Cvek M. Prognosis of luxated non-vital maxillary incisors treated with calcium hydroxide and filled with gutta-percha. A retrospective clinical study. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1992; 8:45–55. PMID: 1521505.

20. Ding RY, Cheung GS, Chen J, Yin XZ, Wang QQ, Zhang CF. Pulp revascularization of immature teeth with apical periodontitis: a clinical study. J Endod. 2009; 35:745–749. PMID: 19410097.

21. Thibodeau B, Teixeira F, Yamauchi M, Caplan DJ, Trope M. Pulp revascularization of immature dog teeth with apical periodontitis. J Endod. 2007; 33:680–689. PMID: 17509406.

22. Hargreaves KM, Geisler T, Henry M, Wang Y. Regeneration potential of the young permanent tooth: what does the future hold? J Endod. 2008; 34:S51–S56. PMID: 18565373.

23. Petrino JA, Boda KK, Shambarger S, Bowles WR, McClanahan SB. Challenges in regenerative endodontics: a case series. J Endod. 2010; 36:536–541. PMID: 20171379.

24. Windley W 3rd, Teixeira F, Levin L, Sigurdsson A, Trope M. Disinfection of immature teeth with a triple antibiotic paste. J Endod. 2005; 31:439–443. PMID: 15917683.

25. Banchs F, Trope M. Revascularization of immature permanent teeth with apical periodontitis: new treatment protocol? J Endod. 2004; 30:196–200. PMID: 15085044.

26. Thibodeau B, Trope M. Pulp revascularization of a necrotic infected immature permanent tooth: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Dent. 2007; 29:47–50. PMID: 18041512.

27. da Silva LA, Nelson-Filho P, da Silva RA, Flores DS, Heilborn C, Johnson JD, Cohenca N. Revascularization and periapical repair after endodontic treatment using apical negative pressure irrigation versus conventional irrigation plus triantibiotic intracanal dressing in dogs' teeth with apical periodontitis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2010; 109:779–787. PMID: 20416538.

28. Wang X, Thibodeau B, Trope M, Lin LM, Huang GT. Histologic characterization of regenerated tissues in canal space after the revitalization/revascularization procedure of immature dog teeth with apical periodontitis. J Endod. 2010; 36:56–63. PMID: 20003936.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download