Abstract

Objectives

In most retrospective studies, the clinical performance of restorations had not been considered in survival analysis. This study investigated the effect of including the clinically unacceptable cases according to modified United States Public Health Service (USPHS) criteria into the failed data on the survival analysis of direct restorations as to the longevity and prognostic variables.

Materials and Methods

Nine hundred and sixty-seven direct restorations were evaluated. The data of 204 retreated restorations were collected from the records, and clinical performance of 763 restorations in function was evaluated according to modified USPHS criteria by two observers. The longevity and prognostic variables of the restorations were compared with a factor of involving clinically unacceptable cases into the failures using Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and Cox proportional hazard model.

Results

The median survival times of amalgam, composite resin and glass ionomer were 11.8, 11.0 and 6.8 years, respectively. Glass ionomer showed significantly lower longevity than composite resin and amalgam. When clinically unacceptable restorations were included into the failure, the median survival times of them decreased to 8.9, 9.7 and 6.4 years, respectively.

Conclusions

After considering the clinical performance, composite resin was the only material that showed a difference in the longevity (p < 0.05) and the significantly higher relative risk of student group than professor group disappeared in operator groups. Even in the design of retrospective study, clinical evaluation needs to be included.

Dentists use a wide range of materials in daily practices to restore tooth structure. Dentists and patients choose a restorative material that has a priority under considerations of various factors. The longevity of restorations is usually the most prior factor among them. It was estimated that the replacement of failed restorations constituted about 60 percent of all operative works of dentists.1 Survival rate has been used as a measure of clinical performance.2 Therefore, how long the restoration could serve in oral cavity has been a concern in evidence-based dentistry. Life expectancy of dental restorative materials have been reported in many clinical researches, but there have been discrepancies in the estimated values among the reports due to the differences in the study design, criteria for case selection, determination of success and failure, estimation of survival time, etc.

Clinical studies have estimated the longevity of the restorations based on prospective or retrospective approaches. Prospective studies have less distortion because they collect data in a controlled study design and observe the assigned factors consistently in a longitudinal manner. However, they require many years in order to achieve enough clinical validation, and there is a possibility of operator- or patient-related bias. On the other hand, retrospective studies have advantages in that they need relatively short time and low cost although the risk of inaccuracy from bias or omission is higher than prospective ones.3-5 With survival analysis, the risk of inexactitude can be compensated by using censored cases that the time of failure cannot be determined and estimating survival rates at a given time.6

For discriminating the status of restoration, various clinical evaluation methods were used.7 Among them, United States Public Health Service (USPHS) criteria has been used the most widely with various modified forms to determine the clinical performance of dental restorations. Many studies used the criteria for the evaluation of the clinical performance, but actually for the calculation of longevity they used only the ratio of the failed restoration. Only a few articles used the grade of 'clinically unacceptable' of the criteria as a failure even though the restoration remained.8-10 Thus, the effect of the inclusion of the cases rated as 'clinically unacceptable' according to the USPHS criteria into the failure on the longevity needs to be evaluated.

This study investigated the effect of including the clinically unacceptable cases according to modified USPHS criteria into the failed data on the survival analysis of direct restorations. For the purpose, the longevity and prognostic variables of direct restorations obtained in a retrospective cross-sectional study were compared by analyzing the data with or without including clinically unacceptable cases into the failures using Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and Cox proportional hazard model.

From July 6, 2009 to August 28, 2009, among the patients who visited department of Conservative Dentistry, Seoul National University Dental Hospital, 232 patients who had direct restorations delivered in this clinic were evaluated. The study was performed under the approval of the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University Dental Hospital. Before the patient visited the clinic, data were collected from the patient's dental record. The information about the patient included the age, sex, and medical and dental history. The information about treatment, such as, tooth type, date of treatment, restorative material, reason for treatment was also included. If there was a record of subsequent retreatment or further treatment, including extraction, endodontic treatment, prosthodontic treatment, etc, it was considered as an event. Its life-span was calculated from the date of the first treatment to the subsequent treatment according to the record. However, if there was no record on the subsequent treatment and thus the restoration was expected to work in the oral cavity, the clinical performance of the restoration was evaluated by two trained observers under the informed consent when the patient visited for his/her appointed treatments. At first, whether the characteristic of the restoration was the same with the record was evaluated. For the restoration that was confirmed to remain, it was regarded as a censored case and evaluated according to the modified USPHS criteria (Table 1). If two observers had disagreement about the grades, a consensus was made between them and recorded. When the restoration did not match the record or was absent, the case was excluded from the data.

The statistical analyses were performed on the data in three phases. First, Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was performed to evaluate the longevity of the restorations without including the cases rated as clinically unacceptable according to the USPHS criteria into the event cases. The direct restorative materials were classified as three groups, such as amalgam (AM), composite resin (CR), and glass ionomer (GI). Conventional glass ionomer and resin-modified glass ionomer were included in the group GI, on the basis of the bonding characteristics that both of them adhered to the tooth structure by an ionic bond. Reasons of restoration were divided into four categories: primary reasons including primary caries, tooth fracture, crack, attrition, abrasion, and erosion; secondary reasons including replacement of old restorations, loss of retention, restoration fracture; pulpal problems including pulp exposure, hypersensitivity and pulpal pain; esthetics including anterior diastema and discoloration of restorations. Secondly, in order to evaluate the effect of the inclusion of clinically unacceptable cases in any criterion of the USPHS criteria into event cases on the calculated longevity of the restoration, the survival analysis was repeated again with including the clinically unacceptable cases into the event cases and both survival estimates were compared. For the restoration that was ethically recommended being replaced due to the clinically unacceptable Charlie grade during the evaluation, its life-span was calculated from the date of the treatment to the evaluation. Finally, multivariate Cox proportional hazard model to analyze the effect of potential prognostic variables on the survival of restorations was also performed for both the data with or without including the clinically unacceptable cases into the failure. The assumed variables were the restorative material, cavity classification, type of the restored tooth, operator group, patient age, gender, and presence of medical history. All the statistical analyses were performed at a level of p < 0.05.

Among the 1,487 restorations from 288 patients evaluated in the survey, 967 direct restorations from 232 patients were included in this report. CR (n = 676, 69.9%) was the most frequently used material, followed by AM (n = 147, 15.2%), and GI (n = 144, 14.9%). In cavity classification, Class V restorations had the largest portion of the cases (n = 499, 51.6%), followed by Class II (n = 198, 20.5%) and Class I (n = 149, 15.4%) restorations. The number of the restorations that had subsequent re-treatment or further treatment records was 204.

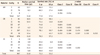

The median survival times and the survival rates at 5 and 10 years of the restorations were presented in Tables 2 and 3. When the clinical performance of the restorations according to the modified USPHS criteria was not included in determining the failure rate, the median survival times of AM, CR, GI and total cases were 11.8, 11.0, 6.8 and 11.0 years, respectively (Table 2). GI showed significantly lower survival estimate compared to CR and AM (Breslow test, p < 0.05, Figure 1a). However, when the restoration rated as clinically unacceptable Charlie in any one of the modified USPHS criteria was included into the failure, the median survival times of them decreased to 8.9, 9.7, 6.4, and 9.3 years, respectively (Table 3). Only the survival estimates of CR and GI showed a significant difference (Breslow test, p < 0.05, Figure 1b). Both five and ten year survival rates were the highest in Class V restorations (76.2% and 55.4%, respectively), followed by Class I (53.6% and 43.2%) and Class II (61.9% and 23.0%) (Table 3). According to the cavity classifications, the statistical difference in the survival estimates between groups showed a little change (Figure 2). When the clinical performance of the restorations according to the USPHS criteria was considered, the difference in the survival estimates between Class I and Class II and Class II and Class V were statistically significant (Breslow test, p < 0.05, Figure 2b).

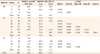

The tooth group, age group, cavity classifications, reasons of treatment, restorative materials, sex and operator group were the prognostic variables that significantly affected the survival of the restorations in a descending order (Cox proportional hazard model, p < 0.05, Table 4). The relative risk of direct restorations were significantly higher in molar teeth than in anterior teeth (p < 0.05). In each variable, the restorations in the group of teenagers, Class II cavities, esthetic reasons, CR and GI, and males showed significantly higher relative risks than those in the groups of thirties and forties, Class I cavities, primary reasons, AM, and females, respectively (p < 0.05, Table 4). Whereas, there were no significant differences in the relative risk between presence and absence of systemic diseases. For these variables, there were no opposite results between before and after considering the clinical performance of each restorations according to the USPHS criteria. For the operator groups, the results were opposite between the two failure criteria.

When the modified USPHS criteria were considered, 505 restorations (57.4%) were rated Alpha or Bravo. Seventy-three cases (7.5%) were rated Charlie and they were changed from censored cases to event cases as failures. The criterion that showed the greatest change in the numbers of event cases was secondary caries (n = 55, 75.3%), followed by marginal adaptation (n = 20, 27.4%), marginal discoloration (n = 11, 15.1%), and hypersensitivity (n = 8, 11.0%). AM restorations changed the most from censored to event (AM, 22 / 147 cases, 15.0%; CR, 46 / 676 cases, 6.8%; GI, 5 / 144 cases, 3.5%). Out of 22 AM restorations, 18 were rated Charlie in secondary caries, 8 in marginal adaptation, and 3 in marginal discoloration. In 46 CR restorations, secondary caries (33 cases) was the most common reason of the Charlie grade and marginal adaptation (10 cases), marginal discoloration and hypersensitivity (7 cases) followed. From 5 GI restorations, secondary caries was in 4 restorations, clinically unacceptable marginal adaptation in two restorations, and marginal discoloration in one restoration. When the survival estimates obtained before and after the restorations rated as clinically unacceptable Charlie were included into the event cases were compared, the increase of the event cases made the two survival estimates marginally different in AM (Log rank test, p = 0.056, Figure 3a) and statistically different in CR (Log rank test, p = 0.032, Figure 3b). However, the survival estimates of GI were not different statistically (Figure 3c).

This study was aimed to investigate the effect of including the clinically unacceptable cases into the failures on the longevity of direct restorations in the survival analysis. In the retrospective study, the survival time was calculated from the failure event. Although a restoration needed retreatment due to secondary caries, lack of marginal adaptation, partial loss, and so on, in most retrospective studies, it has not been regarded as an event if it retained in the oral cavity.11,12 In prospective studies, the clinical performances of these cases were generally reported using the USPHS criteria. Roulet reported the 6 year survival rate of AM restorations (87%) according to the USPHS criteria.13 However, most prospective clinical studies had difficulties to continue the investigation for a long time and were obliged to deal with relatively short clinical performances of the restorations for only a few years.8,9 In the viewpoint of evaluation of the long-term clinical performance of the dental restorations, retrospective studies can be more suitable than prospective ones.4 In order to reflect the clinical performance of the restorations to the survival estimates of the retrospective observation, intra-oral evaluation of the restorations with an appropriate criteria should be considered.

In the present study, the restorations that were graded as Charlie according to the USPHS criteria were regarded as failure in the ethical point of view that a dentist should recommend replacement of these restorations. The influence of applying these strict criteria on the survival analysis was investigated by comparing the survival estimates obtained before and after including the clinically unacceptable Charlie cases into event cases. When the clinically unacceptable cases were included in the failures, the median survival times and survival rates of the restorations decreased from those without including the cases into the failures (Tables 2 and 3). When the clinical performance of the restorations according to the modified USPHS criteria was not considered in determining the failure rate, GI showed significantly lower survival estimate compared to CR and AM (Figure 1a). However, after considering the clinical performance, the survival estimate of GI was significantly different only from CR (Figure 1b). Therefore, considering the clinical performance apparently affected the comparison of the survival estimates of restorative materials. From the Cox proportional hazard model, the p values showed a trend to increase slightly. Although no apparent changes of the relative risks and significance of the correlation were observed in each variable, those for the operator groups showed opposite results (Table 4). The two survival estimates of CR restorations showed a significant difference before and after including the Charlie rated cases into the event (Figure 3b). Those of AM restorations showed a marginal difference and those of GI showed no difference. Therefore, in the design of the future retrospective study, it is recommended that intra-oral evaluation of the clinical performance of each restoration be included in the determination of the failure.

This retrospective study also evaluated the clinical performance of the direct restorations in comparing the longevity between materials and cavity classifications and in assessing the prognostic factors. Despite retrospective study, the assessment in this study was more reliable than the data obtained in surveys that were used in most retrospective studies, because this study used the treatment records of a university dental hospital and well-controlled operative procedures in a department. However, the clinical practice was performed by the clinicians of university dental hospital who were highly interested in the treatment, so that the difference from the result of the whole population should be considered. In this study, the use of AM restorations decreased continuously (unpublished data), and CR has surpassed AM in the proportion of posterior direct restorations since 2000. The proportion of direct AM restorations in this study (15.2%) was higher than that in Finland (4.8%).14

There was no difference in the survival estimates of AM and CR restorations. Opdam et al. showed higher survival rate in posterior CR than AM.5 On the other hand, previous comparisons of CR and AM restorations in posterior teeth are generally in favor of the AMs.15,16 This controversy was from the absence of comparison for each stratum of cavity classification. In the present study the longer survival time of CR might result from the fact that the material was used in Class V cavity at a higher proportion (Table 2). Like most previous studies, the median survival time of CR (10.9 years) in Class V restorations was not different from that of GI (10.3 years) in the present study.4,12,13,17 Meanwhile, AM restoration had only 8 Class V restorations that were less influenced from the occlusal force than occlusal restorations. Amalgam was used mostly in Class I and Class II cavities. The survival estimate of Class II restorations was less than that of Class V restorations because of direct effect of the occlusal force (Figure 2b). The result showed that cervical restorations worked longer in the oral cavity than occlusal restorations. It suggests that occlusal forces affected directly to the clinical performance of the restorations.

In each stratum of cavity classification, the clinical performance of AM restorations was better than that of CR restorations in Class I restorations (Table 3). The median survival times of Class I and Class II AM restorations were 10.0 years and 7.9 years, respectively, whereas the median survival times of Class I and Class II CR restorations were not different statistically as 5.0 years and 7.8 years, respectively (Table 3). The findings of this study were similar with previous retrospective studies which suggested that AM had a lower failure rate than CR.18,19 The result that the survival time of Class II AM restorations was shorter than Class I AM restorations also coincided with several reports about posterior restorations.20,21 However, if the clinical performance was not considered, the difference between the classifications disappeared in CR restorations (Table 2).

According to the study design, there have been considerable controversies about the effect of prognostic variables on the longevity of the restorations. In this study, the factors that affected the longevity of restorations were tooth group, age, cavity classification, and reasons of treatment, materials, gender and operator group in a descending order (Table 4). However, in most previous studies, it has been reported that the cavity type had a significant influence on the longevity of the restorations.4,5,12 Bernardo et al. showed that the clinical performance of the restorations was independent of the restored surface.22 They also affirmed that the type of tooth and size of restoration had no influence on the longevity. Van Nieuwenhuysen et al. reported that age of the patients had an effect on the survival of the restorations.23 Since there have been controversies on the association of the prognostic variables with the longevity of restorations, it should be of paramount importance in the future investigations to standardize study design. Although CR and GI restorations showed higher relative risks than AM restorations, appropriate repair of CR restorations through well-timed or at early checkup will improve the longevity of the restorations. Therefore repair of CR restorations cannot be overemphasized.24 Indications of repair and the criteria on whether repair and replacement are censored or in an event should be established, and future studies on their longevity will be needed.

In the survival analysis, the longevity and prognostic variables showed a similar trend before and after considering the clinical performance evaluated according to modified USPHS criteria. However, after considering the clinical performance, composite resin showed a difference in the longevity (p < 0.05) and the significantly higher relative risk of student group than professor group disappeared in operator groups. Moreover, the survival estimates of CR restorations showed a significant difference between Class I and Class II. Therefore, clinical evaluation needs to be included even in the design of retrospective study.

Figures and Tables

| Figure 1Comparison of survival estimates according to restorative materials using Kaplan-Meier survival analysis. (a) When clinically unacceptable Charlie cases were not included into the failure, GI showed significantly lower survival estimate compared to CR and AM (Breslow test, p < 0.05); (b) When clinically unacceptable Charlie cases were included into the failure, only the survival estimates of CR and GI showed a significant difference (Breslow test, p < 0.05). AM, amalgam; CR, composite resin; GI, glass ionomer. |

| Figure 2Comparison of survival estimates according to cavity classifications using Kaplan-Meier survival analysis. According to the cavity classifications, the statistical difference in the survival estimates between groups showed a little change. (a) When clinically unacceptable Charlie cases were not included into the failure, there were significant differences between Class I and Class II, Class I and Class IV, Class II and Class III (Log rank test, p < 0.05), and Class II and Class V (Breslow test, p < 0.05); (b) When clinically unacceptable Charlie cases were included into the failure, only the difference in the survival estimates between Classes I and II and Classes II and V were statistically significant (Breslow test, p < 0.05). AM, amalgam; CR, composite resin; GI, glass ionomer. |

| Figure 3Comparison of survival estimates using Kaplan-Meier survival analysis between with and without including the clinically unacceptable Charlie cases into the failure cases. (a) Amalgam restorations showed marginally different survival estimates (Log rank test, p = 0.056); (b) Composite resin restorations showed significantly different survival estimates (Log rank test, p < 0.05); (c) The survival estimates of glass ionomer restorations were not different statistically (Log rank test). USPHS, United States Public Health Service. |

Table 2

Pairwise comparison of survival estimates between cavity classifications when the clinical performance of the restorations in the oral cavity was not considered, that is, when the clinically unacceptable Charlie cases according to the United States Public Health Service (USPHS) criteria were not included into the failure

Notes

References

1. Mjör IA. Amalgam and composite resin restorations: longevity and reasons for replacement. Replacement of AM restorations. Quality evaluation of dental restorations - criteria for placement and replacement. 1989. Chicago: Quintessence Publishing Co;61–68.

2. Onal B, Pamir T. The two-year clinical performance of esthetic restorative materials in noncarious cervical lesions. J Am Dent Assoc. 2005. 136:1547–1555.

3. Chadwick B, Treasure E, Dummer P, Dunstan F, Gilmour A, Jones R, Phillips C, Stevens J, Rees J, Richmond S. Challenges with studies investigating longevity of dental restorations-a critique of a systematic review. J Dent. 2001. 29:155–161.

4. Manhart J, Chen H, Hamm G, Hickel R. Buonocore Memorial Lecture. Review of the clinical survival of direct and indirect restorations in posterior teeth of the permanent dentition. Oper Dent. 2004. 29:481–508.

5. Opdam NJ, Bronkhorst EM, Roeters JM, Loomans BA. A retrospective clinical study on longevity of posterior composite and amalgam restorations. Dent Mater. 2007. 23:2–8.

6. Kubo S, Kawasaki A, Hayashi Y. Factors associated with the longevity of resin composite restorations. Dent Mater J. 2011. 30:374–383.

7. Goldberg AJ, Rydinge E, Santucci EA, Racz WB. Clinical evaluation methods for posterior composite restorations. J Dent Res. 1984. 63:1387–1391.

8. Arhun N, Celik C, Yamanel K. Clinical evaluation of resin-based composites in posterior restorations: two-year results. Oper Dent. 2010. 35:397–404.

9. Daou MH, Tavernier B, Meyer JM. Clinical evaluation of four different dental restorative materials: one-year results. Schweiz Monatsschr Zahnmed. 2008. 118:290–295.

10. Alves dos Santos MP, Luiz RR, Maia LC. Randomized trial of resin-based restorations in Class I and Class II beveled preparations in primary molars: 48-month results. J Dent. 2010. 38:451–459.

11. Scholtanus JD, Huysmans MC. Clinical failure of class-II restorations of a highly viscous glass-ionomer material over a 6-year period: a retrospective study. J Dent. 2007. 35:156–162.

12. Mjör IA, Shen C, Eliasson ST, Richter S. Placement and replacement of restorations in general dental practice in Iceland. Oper Dent. 2002. 27:117–123.

13. Roulet JF. Longevity of glass ceramic inlays and amalgam-results up to 6 years. Clin Oral Investig. 1997. 1:40–46.

14. Forss H, Widström E. From amalgam to composite: selection of restorative materials and restoration longevity in Finland. Acta Odontol Scand. 2001. 59:57–62.

15. Goldstein GR. The longevity of direct and indirect posterior restorations is uncertain and may be affected by a number of dentist-, patient-, and material-related factors. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2010. 10:30–31.

16. Antony K, Genser D, Heibinger C, Windisch F. Longevity of dental amalgam in comparison to composite materials. GMS Health Technol Assess. 2008. 4:Doc12.

17. Rho YJ, Namgung C, Jin BH, Lim BS, Cho BH. Longevity of direct restorations in stress-bearing posterior cavities: a retrospective study. Oper Dent. 2000. (in press).

18. Mjör IA. The reasons for replacement and the age of failed restorations in general dental practice. Acta Odontol Scand. 1997. 55:58–63.

19. Mjör IA, Dahl JE, Moorhead JE. Age of restorations at replacement in permanent teeth in general dental practice. Acta Odontol Scand. 2000. 58:97–101.

20. da Rosa Rodolpho PA, Cenci MS, Donassollo TA, Loguércio AD, Demarco FF. A clinical evaluation of posterior composite restorations: 17-year findings. J Dent. 2006. 34:427–435.

21. Burke FJ, Cheung SW, Mjör IA, Wilson NH. Restoration longevity and analysis of reasons for the placement and replacement of restorations provided by vocational dental practitioners and their trainers in the United Kingdom. Quintessence Int. 1999. 30:234–242.

22. Bernardo M, Luis H, Martin MD, Leroux BG, Rue T, Leitão J, DeRouen TA. Survival and reasons for failure of amalgam versus composite posterior restorations placed in a randomized clinical trial. J Am Dent Assoc. 2007. 138:775–783.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download