Abstract

In spite of being several results of efficacy obtained by randomized controlled trials about new health technologies, evidences related to real effectiveness confirmed by head-to-head direct comparison should be needed in order to improve qualities of healthcare. The comparative effectiveness evaluation (CEE) as outcomes research have suggested as the important tool for developing evidence-based information to patients, clinicians, and other decision makers about which technologies are most effective for which patients under specific circumstances. Four major methods of outcomes research are applied as systematic reviews and meta-analyses, cohort studies using registries, linkage of large databases, and pragmatic clinical trials. Through activating the CEE, the best and most effective technologies should be adopted rapidly in routine clinical practices.

Figures and Tables

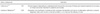

Fig. 1

The range of outcomes associated with heart failure. (A) Range of clinical outcomes associated with heart failure. (B) Integration of multiple endpoints (From Spertus JA, et al. Am Heart J. 2002;143:636-42).16)

References

1. Antman EM, Lau J, Kupelnick B, Mosteller F, Chalmers TC. A comparison of results of meta-analyses of randomized control trials and recommendations of clinical experts: treatments for myocardial infarction. JAMA. 1992. 268:240–248.

3. Reynolds JL, Whitlock RM. Effects of a beta-adrenergic receptor blocker in myocardial infarction treated for one year from onset. Br Heart J. 1972. 34:252–259.

4. Roland JM, Wilcox RG, Banks DC, Edwards B, Fentem PH, Hampton JR. Effect of beta-blockers on arrhythmias during six weeks after suspected myocardial infarction. Br Med J. 1979. 2:518–521.

5. Pratt CM, Roberts R. Chronic beta blockade therapy in patients after myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 1983. 52:661–664.

6. Baber NS, Lewis JA. Beta-adrenoceptor blockade and myocardial infarction: when should treatment start and for how long should it continue? Circulation. 1983. 67(6 Pt 2):I71–I77.

7. Pedersen TR. The Norwegian Multicenter Study of Timolol after Myocardial Infarction. Circulation. 1983. 67(6 Pt 2):I49–I53.

8. Hampton JR. The use of beta blockers following myocardial infarction-doubts. Eur Heart J. 1983. 4:Suppl D. 151–157.

9. Pratt CM, Young JB, Roberts R. The role of beta-blockers in the treatment of patients after infarction. Cardiol Clin. 1984. 2:13–20.

11. Gilbody SM, House AO, Sheldon TA. Outcomes research in mental health: systematic review. Br J Psychiatry. 2002. 181:8–16.

12. Caper P. Variations in medical practice: implications for health policy. Health Aff (Millwood). 1984. 3:110–119.

13. Brook RH, Lohr K, Chassin M, Kosecoff J, Fink A, Solomon D. Geographic variations in the use of services: do they have any clinical significance? Health Aff (Millwood). 1984. 3:63–73.

14. Curtis JR, Rubenfeld GD, Hudson LD. Training pulmonary and critical care physicians in outcomes research: should we take the challenge? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998. 157(4 Pt 1):1012–1015.

15. Institute of Medicine. Initial national priorities for comparative effectiveness research. 2009. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press;13.

16. Spertus JA, Tooley J, Jones P, Poston C, Mahoney E, Deedwania P, et al. Expanding the outcomes in clinical trials of heart failure: the quality of life and economic components of EPHESUS (EPlerenone's neuroHormonal Efficacy and SUrvival Study). Am Heart J. 2002. 143:636–642.

17. Wennberg JE. Dealing with medical practice variations: a proposal for action. Health Aff (Millwood). 1984. 3:6–32.

18. Salive ME, Mayfield JA, Weissman NW. Patient Outcomes Research Teams and the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. Health Serv Res. 1990. 25:697–708.

19. Manchikanti L, Falco FJ, Boswell MV, Hirsch JA. Facts, fallacies, and politics of comparative effectiveness research: Part I. basic considerations. Pain Physician. 2010. 13:E23–E54.

20. Bruner DW. Outcomes research in cancer symptom management trials: the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) conceptual model. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2007. (37):12–15.

21. Vogenberg FR. Comparative effectiveness research: valuable insight or government intrusion? P T. 2009. 34:684–685.

22. Roberts I, Yates D, Sandercock P, Farrell B, Wasserberg J, Lomas G, et al. Effect of intravenous corticosteroids on death within 14 days in 10008 adults with clinically significant head injury (MRC CRASH trial): randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2004. 364:1321–1328.

23. Karanicolas PJ, Montori VM, Devereaux PJ, Schunemann H, Guyatt GH. A new 'mechanistic-practical' framework for designing and interpreting randomized trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009. 62:479–484.

24. ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial. Major outcomes in high-risk hypertensive patients randomized to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker vs diuretic: The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT). JAMA. 2002. 288:2981–2997.

25. Dougherty D, Conway PH. The "3T's" road map to transform US health care: the "how" of high-quality care. JAMA. 2008. 299:2319–2321.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download